Unexpected killers of your international energy deal

Sashe Dimitroff,Haynes and Boone LLP, Houston

Jean-Pierre Douglas-Henry,Lawrence Graham LLP, London

An unexpected crisis can kill an international energy project. Some crises are predictable, such as a breach of contract by a critical vendor. It is common sense to plan for these "predictable" crises. But recent experience shows that traditional pre-planning makes certain assumptions that are often wrong and can be fatal to an international energy deal. For example,

- "I'll choose English or New York law:" While many energy projects use standard contract terms like choice of law, force majeure and arbitration provisions, many courts will apply local law when deciding whether to uphold your rights or seize your assets.

- "My liability is limited because I used a special purpose entity (SPE) that has no assets:" Some jurisdictions will allow the assets of subsidiaries, affiliates or even a parent company to be seized as security for a potential award or to pay off a judgment.

- "I can avoid local courts by arbitration in a neutral forum:" Many jurisdictions refuse to recognize arbitration clauses and go forward in local courts under local law.

- "I won my arbitration:" A surprising number of emerging market jurisdictions refuse to enforce arbitral awards and insist on "re-trying" the merits locally.

Other crises are not as predictable. For example,

- The BP oil spill: The spill resulted in a moratorium on drilling in the Gulf of Mexico.

- Hugo Chavez: The Venezuelan government nationalized certain energy projects with foreign investors and offered a fraction of the true value of the project as "compensation."

These issues can be fatal or extremely expensive. The purpose of this article is to identify the misplaced assumptions parties often make when negotiating the terms of a deal and to offer an outline of solutions.

Assumption 1: Standard clauses are safe. They protect us against unplanned events or local courts.

Many international oil and gas projects are in emerging markets. They are often in locations that are rich in oil and gas but have unfavorable local laws and unstable political regimes. The standard approach to negotiate a contract in these markets is to use familiar terms to protect the project from unforeseen events or undue local law and influence. So, for example, investors choose English or US law to govern the contract, opt for arbitration in a neutral forum at an established arbitral institute like the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) or the London Court of International Arbitration (LCIA).

In addition to getting a reliable system of law in a neutral jurisdiction, the major appeal of this approach is the relative enforceability of foreign arbitral awards under the New York Convention, which is often cited as the most successful multi-lateral treaty in history. But in many instances, this approach fails.

A. Local laws may be mandatory.

Local law may be mandatory even though the parties have a different choice of law provision in their contract. In places like China, certain African jurisdictions and parts of South America, if property rights are involved (e.g., mining licenses, concessions, etc.), local courts will encumber assets due to project indebtedness that may be real or made up (e.g., for unpaid local taxes). These encumbrances cannot be avoided by contractually choosing a foreign law and may subject a foreign investor to having the local authorities physically take over its refinery, pipeline or in-country bank accounts.

B. Standard contract provisions may not give standard results.

In many contracts, provisions like arbitration and force majeure clauses are standard boilerplate and are often copied from one contract to the next. The parties assume they are protected because their terms have long been used and accepted.

Recent world events demonstrate these are no longer valid assumptions. Arbitration clauses offered little relief to foreign investors when Venezuela effectively cancelled them after the contracts were signed. For example, Hugo Chavez's government successfully challenged Venezuela's treaty obligations to foreign investors that provided them with the right to have investment disputes resolved through ICSID arbitration which is governed and enforced by the World Bank. Venezuela effectively ripped up the investment treaty. It now uses its own courts and its own laws to enforce (or negate) international contracts that were well-crafted and had no intention of being construed or enforced in Venezuela using Venezuelan law.

Similarly, in recent months, the BP oil spill led to a US government-issued moratorium on drilling in the Gulf of Mexico, one of the most prolific drilling sites in the world. As a result, several operators indicated that they will not (because they cannot) perform their contractual duties with drilling companies due to force majeure, that is, forces beyond their control. Although the specific language of force majeure provisions generally controls resolution of the dispute (whether boilerplate or not), courts carefully review them and may decide to apply laws never contemplated by the contract (e.g., federal maritime law) in forums never specified by the parties. Depending on what law applies, the outcome of the disputes may differ significantly.

Assumption 2: You can use special purpose entities to limit risk and liability.

Many oil and gas deals involve an SPE such as a limited liability partnership or an offshore corporation that is created for the specific transaction. Generally, these SPEs have few assets and are considered judgment proof. The assumption is that by using such an SPE, a party's risk and liability is limited.

This assumption can be deadly. Some jurisdictions will allow the assets of subsidiaries, affiliates or even a parent company to be seized as security for a potential award or to pay off a judgment, even though these entities had no involvement with the dispute, are not parties to the contract, and the parties' contractual choice of law does not allow for such remedies. For example, the authors recently won such relief even though the contract was to be performed in Africa, had a valid arbitration clause and had an English choice of law provision - the defending company had assets in the Middle East and Central America and the laws of those countries allowed legal remedies (based upon group enterprise theory) not recognized by English law.

Assumption 3: You can avoid local courts and local laws through arbitration.

Arbitration is the legal equivalent of a common currency. It enables international investors to do cross-border deals in countries whose laws and legal systems would otherwise present too much risk. And, given that the majority of the world's undeveloped natural resources are located in emerging markets, arbitration is often viewed as the only viable dispute resolution mechanism.

But, arbitration is not a panacea. Hugo Chavez's ripping up of Venezuela's investor treaties demonstrates the vulnerability of arbitration clauses to political intervention and it is difficult for investors to protect against these types of actions. There is also an increasing tendency for the courts in emerging markets to not recognize arbitration agreements (pursuant to which the parties agree to arbitrate rather than litigate disputes arising under their contracts) to enable a local party to pursue or defend claims through the local courts.

Assumption 4: You can enforce your arbitration awards.

It is neither well known nor publicized that these same jurisdictions, with enormous foreign investment in their energy and associated infrastructure projects, not only fail routinely to recognize foreign arbitral awards, but they also subject them to a broad public policy filter. Although there is an exception in the New York Convention that allows local courts to refuse enforcement on this ground, the increasing use of the exception in certain jurisdictions distorts it out of all recognition. For example,

- In Kazakhstan the local courts will review the merits of your case before they will consider recognizing your already-won arbitration award;

- In Russia an arbitration award will not be enforceable if it is against the perceived national interest or relates to strategic assets;

- In some Middle Eastern countries and in China, enforcement is subject to political influence and local officials may prevent your arbitration award from being enforced; and

- In many African jurisdictions, you have to re-litigate the underlying case, even after winning an award in arbitration, before a judiciary that may be questionable at best.

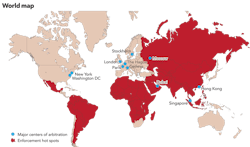

As a result, investors face reduced certainty about whether they can enforce an arbitral award in the places that matter most (see map).

Planning is critical

An international energy project can be destroyed by applying commonly held assumptions without learning from recent history and trends. Considering today's economy and world events, it is critical to use non-traditional legal and business analysis for defensive structuring of deals (aka how to avoid getting tied up in expensive, fruitless disputes for years). Surprisingly, this means that trial lawyers are spending more time working with the deal lawyers to de-risk transactions, particularly when the transactions will take place abroad in an emerging or even frontier market.

The key is to work backwards. That means the parties should plan and structure the deal by getting and then coordinating local and foreign law advice to ensure they understand what law applies to which aspects of the project. Local advice in a vacuum is almost always bad advice. While there is no single solution to every problem, there are common themes that are useful in planning. For example, consider:

- Who is your counter-party (e.g., government or individual, single company or an SPE)? The critical question is what will you need if the deal ends badly – assets to reach or assets to protect?

- What is the location and nature of the key assets (are they at risk and can they be protected using laws and procedures that are not provided for in the contract)?

- Where are the key contractual duties to be performed and do those activities implicate other laws that are not specified in your contract? For example, does the contract have appropriate limitation and exclusion of liability provisions that deal with your particular set of risks under the applicable laws where your project is located?

- Do you need political risk insurance and does the value of the project make such precautions worth it? For example, both private insurance companies and the US government offer political risk insurance for energy projects in unstable areas.

- If the deal goes badly, how will you be able to enforce your bargain? For example, will you have accessible cash or assets to get paid and if so, in what form and are there offshore cash flows that may be used to avoid jurisdiction risk?

The ultimate goal is to prudently use legal counsel to tailor your dispute resolution mechanisms to increase certainty of outcome.

Conclusion

In summary, the same old assumptions are causing disastrous new results for energy companies. This requires a new approach. Lawyers must be able to not only paper the transaction but to also understand and provide for the consequences if the deal goes wrong. Pre-planning is the key and long-held assumptions are the enemy. You will never be able to anticipate every potential disaster – who would have guessed that BP and Hugo Chavez would have presented the challenges they have – but being forewarned is forearmed. OGFJ

About the authors

More Oil & Gas Financial Journal Current Issue Articles

More Oil & Gas Financial Journal Archives Issue Articles

View Oil and Gas Articles on PennEnergy.com