Reserve based finance

A Tale of Two Markets - Part 2

| Jason Fox Bracewell & Giuliani London | Dewey Gonsoulin Bracewell & Giuliani Houston | Kevin Price Société Générale London |

This is the second part of a four part article examining the evolution, practices and future of the reserve based finance markets in the US and internationally. Part 1 appeared in the January 2014 issue of OGFJ. In this, Part 2, the authors examine facility structures and sources of debt for the upstream sector in the North American market (these areas in the international market were reviewed in Part 1), amortization and reserve tails, reserve analysis and bankable reserves, as well as The Banking Case and assumption determination.

Description of US RBF market

US producers of oil and gas have a variety of financing options depending on certain factors. The variables include: type and location of the company's assets, overall creditworthiness of the producer, existence or absence of an equity sponsor, operating history, and experience of the management team. Companies that have producing assets (and hence, usually have good cash flow) will often access the commercial bank markets and establish a traditional borrowing base revolving line of credit. Other producers may have little or no producing assets and must look to the mezzanine and Term Loan B market (institutional debt funds) for more expensive term loans. Finally, many publicly listed companies access the public markets and issue high yield bonds on either a secured or unsecured basis. Below is a brief description of some of the more common types of upstream financing alternatives available to independent exploration and production companies in the US.

Bank revolving lines of credit

Commercial banks typically offer two types of revolving lines of credit to upstream oil and gas producers. First, an asset based line governed by a borrowing base tied to the present value of the company's proved oil and gas reserves, and second, a more traditional corporate credit facility which is not governed by a borrowing base but by backward looking EBITDA covenants. The borrowing base product is much more prevalent as most companies don't have the creditworthiness required to have a simple EBITDA (earnings) based loan. The borrowing base is redetermined two times a year (although sometimes quarterly if rapid changes to the reserves are expected) using a reserve report. These loans are secured by the reserves as well as by substantially all of the personal property assets of the borrower and its subsidiaries. Financial ratios typically include a leverage test (debt to EBITDA) and a current ratio (current assets to current liabilities). Banks providing these loans typically lend against SEC Proved Developed Producing (PDP) and Proved Developed Non-Producing (PDNP) classified reserves. Additionally, they may give a small percentage of value to Proved Undeveloped Reserves (PUDs). Cash flow (EBITDA based) revolvers are usually available to investment grade or sometimes "cross-over" companies (i.e. those close to IG grade or large non publically rated companies where banks own internal ratings place them at the IG end of the credit scale). These loans are often unsecured and are not governed by a borrowing base.

Unlike the international market, in US borrowing base loans there are no cover ratios in the loan documentation because they are considered superfluous; the ability to reset the borrowing base if loan to value metrics shift is considered more than sufficient to protect the lenders. In determining the borrowing base, each bank does its own analysis, compares the results to its own internal guidelines and then agrees or does not agree with the borrowing base amount requested by the borrower or proposed by the bank serving as the administrative agent for the loan facility (see the section below on the Banking Case).

Second lien

Some commercial banks and other financial institutions will make available to producers second lien secured term loan financings. These term loans often have a bullet repayment and carry a higher interest rate than the first priority secured revolving lines. Certain banks offer this product in conjunction with their provision of the first lien revolver and it is utilized in situations where the first lien lenders are unable to "stretch" the borrowing base to a level that affords the borrower the requisite amount of debt it is seeking. Because of the higher interest rate, many borrowers will repay this debt when either a liquidity event occurs or alternatively from increases in borrowing base availability when they occur. Senior first lien borrowing base lenders will, however, usually restrict repayments and prepayments of the second lien and consent from such lenders is often necessary before the borrower can retire such debt.

Mezzanine loans

Companies that do not have significant producing reserves (and in some cases, they may not have significant proved reserves) often turn to the mezzanine loan market to obtain development debt capital. These are typically higher interest term loans with tight covenants and extensive controls on funding. In the absence of a regulator imposed development plan, as seen in offshore fields in the international market, the borrower and the lender usually rely on an "approved plan of development" or "APOD" agreed in the financing documentation as the guiding plan on how the loan proceeds are to be used to pay the costs of development. In this way the facilities seek to mitigate the "development certainty" risk covered by heavy government regulation of offshore developments in other parts of the world. These loans are secured by substantially all of the assets of the borrower and, because there is no borrowing base to regulate the loan to value metrics, a collateral coverage ratio is typically included in the list of financial ratios. These loans are provided by financial institutions that specialize in mezzanine lending. Energy Infrastructure Group (EIG), Carlyle Group, Apollo and Highbridge are all examples of institutions that have raised large funds to make these types of investments. These loans are often repaid through a sale of assets or a takeout financing provided by senior banks once the fields start to produce.

High yield bonds

Companies that have access to the public markets have been very successful in the past few years issuing high yield bonds. Most of these transactions are at least $100,000,000 in size and many are much larger (at least $300m particularly at first issuance as most investors want to see a minimum liquidity in the bond and below this there may be a liquidity premium). They are typically done on an unsecured basis but secured high yield transactions are not uncommon. If secured, the bonds rank second in priority to the borrower's traditional senior bank facility. Some borrowers build in the flexibility under their senior bank facility to issue these bonds so long as such bonds meet certain parameters (maturity date later than senior bank maturity date, covenants not more restrictive than senior bank covenants, etc.) In many cases banks might also require also that the borrowing base reduces by a percentage (typically 25% or 30%) of the principal amount of the bonds issued (this feature compensates for the increased interest burden of the high yield notes). Institutional investors such as insurance companies are the primary holders of such bonds. The combination of subordinated or unsecured bonds and a secured corporate revolver or borrowing base facility represents the classic debt capital structure of the US independent exploration and production company.

Volumetric production payments

Another financing alternative for US producers of oil and gas is a volumetric production payment (VPP). A VPP is a limited term, non-operated property interest, typically created by means of a conveyance, that entitles the VPP holder to receive a specified share of the hydrocarbons produced from the underlying property or properties of the VPP seller (the producer) during each specified period (daily or monthly), free of any taxes or costs of production, in exchange for an upfront payment from the VPP holder.

A VPP expires when a producer has delivered a specified quantity of hydrocarbons to the holder. The scheduled volumes that a holder is entitled to receive under a VPP are typically determined based on a portion (usually 60% to 80%) of the Proved Developed Producing (PDP) reserves. If the holder does not receive its specified volume of hydrocarbons during any specified period, it is entitled to receive additional volumes in future periods. The quantity of additional volumes is determined using a formula that converts the value of the hydrocarbons the holder failed to receive into an equivalent value of hydrocarbons in a future period. The formula also includes an interest component to compensate the holder for the delay in delivery.

VPPs are often used by producers with suboptimal creditworthiness as a financing alternative during periods of high commodity prices and low interest rates when such producers are motivated to obtain favorable hedging and lending terms. Perceived advantages of a VPP for a producer include: (i) maintaining operational control over the burdened properties while shifting reserve risk from the producer to the VPP holder — a producer's obligation to deliver hydrocarbons under a VPP only arises, as and when the producer produces hydrocarbons from the properties burdened by the VPP, (ii) limited recourse to the fields — VPPs are typically only secured by the properties burdened by the VPP and (iii) the ability to obtain a commodity and interest rate hedge without ongoing margining requirements.

The primary benefit of a VPP to a holder is that, unlike a secured loan, a VPP provides the holder with a direct ownership interest in the underlying properties. In many states, including Texas, this interest is characterized as a real property interest and therefore would not be included in the producer's estate if the producer is subject to a bankruptcy proceeding. Consequently, to the extent the producer continues to produce hydrocarbons after it files for bankruptcy, the holder should continue to receive its share of production without being impeded by the automatic stay.

In many cases historically a VPP structure may have allowed a higher leverage for a given amount of reserves or production to be raised than an equivalent RBL loan with hedging. However, with the rise of the non-conventional resource plays in the US and the ability to get the bank market to accept more aggressive hedging covenants associated with them, VPP's are less common in the US market than they have been in the past partly because they do not offer the same leverage advantage over conventional RBL's (with hedging) for these kinds of resources.

Amortization and reserve tails

There are some fundamental differences in approach between the international and US markets in the area of tenors and amortization and in relation to the issue of a "reserve tail".

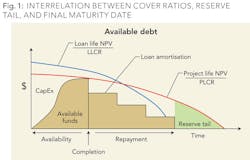

In the international markets, facilities are sized and their tenors are set to ensure that they fully amortize through cash flow, usually in a fairly straight line basis after an initial grace period, by the "Final Maturity Date". Following the traditional project financing model, lenders are generally not willing to take a refinancing risk so it is axiomatic that net cash flows from the fields should be sufficient to repay all debt by the Final Maturity Date. Final Maturity Dates are in part driven by the market and how long the market is willing to go out to (currently a maximum of seven years)1 but they are also driven by the concept that field net cash flows must be sufficient to fully amortize all debt by the Final Maturity Date. The Final Maturity Date will be the earlier of a preset long stop date and the "Reserve Tail Date". The Reserve Tail Date is the date by which a pre-set portion (usually 25%) of the initial approved reserves taken into account in the first Banking Case remain to be recovered. The reserve tail will be reviewed and, potentially re-set, at the time of each Banking Case and therefore the Final Maturity Date of the debt may move in or out at the time of each Banking Case redetermination (but subject of course to a maximum possible Final Maturity Date which is set in stone at the outset).

Debt reductions are also driven by a retesting of cover ratios each time a Banking Case is adopted. The reserve tail concept is an overhang of early development loans designed to ensure repayment of debt comfortably before the abandonment of offshore fields becomes an issue (when the CAPEX for abandonment can be substantial). The tail also adds additional protection in the event of an oil price drop (as fewer reserves will be economic) and in the case of an unexpected reduction of reserves or acceleration of extraction.

As fields have gotten smaller, particularly in the North Sea, the reserve tail itself as a structural feature can in some instances be a less effective credit control as a 25% reserve tail may not equate to a 25% NPV value tail because of the effect of abandonment CAPEX on the NPV. This can be particularly marked on smaller marginal fields. The reserve tail feature can also be particularly important on shorter life offshore fields where, because of the abandonment CAPEX, the Project Life NPV can be less than the Loan Life NPV (due to the effect of the abandonment costs) this is illustrated in the example given in Figure 1.

There are some important differences between the approach just described and the approach in the US. First, available maximum maturities in the US are currently five years, which is shorter than in the international market. Second, while some US RBL facilities step down in a straight line way, most borrowing base lines of credit provide for a bullet repayment at the maturity date of the revolver. The concept of a Reserve Tail Date does not apply in US RBL and, as indicated below, nor do documented cover ratios in the case of a revolving line of credit (it is worth noting, however, that such ratios are critical in the context of a term loan structure).

In the US, the whole approach is very focused on collateral cover (i.e. are there sufficient reserves to see that, on enforcement, banks will get repaid by sale of the assets or by a refinancing led by a financial institution offering a debt product that is further down the balance sheet?). In the international market the approach is more focused on monitoring actual business plan cash flows (i.e. will cash flows be sufficient to see a stepped reduction to full repayment of the facility by the Final Maturity Date?).

Reserve analysis and bankable reserves

In the US, the approach to reserve reporting is driven by the SEC's requirements and this in turn has driven reserve analysis by lenders and, to some extent, the whole US RBF market. Until a revision in late 2008, (the first time the SEC reviewed its rules in this area for some 25 years) independents were only allowed to report proved reserves. While the SEC does now allow the disclosure of probable and possible reserves to investors, the US bank debt and equity markets were long established to be almost entirely focused on proved reserves. In relation to the bank debt markets (and the "Registered" and "with registration rights" sections of the 144A bond markets), this approach remains the case today.

In the US, each bank providing a senior borrowing base revolving line of credit will make its own calculation of collateral value when determining the borrowing base at each redetermination date. This is done by applying a "risk factor" to each component of the Proved reserve category in the reserve report. Each bank has its own approach, but typically banks will give value to 100% of Proved Developed Producing Reserves (PDP) and perhaps 75% of Proved Developed Non-Producing Reserves (PDNP) and 50% of Proved Undeveloped Reserves (PUD). These calculations are further adjusted ("risked") and limited by the banks by others variables. For instance, most banks won't allow the PUD portion to contribute more than a certain percentage of the Borrowing Base Amount (typically 20% or 30%) and there may be further limits if a large percentage of PDP comes from one or two wells only.

One of the reasons so little value is given to PUDs in US RBL is that, in contrast to many other jurisdictions where the regulatory framework may impose obligations to carry out CAPEX and drill a specified number of wells, in the US context there can be huge uncertainty over whether onshore PUDs, for example, are ever drilled. This is particularly the case for onshore fields which lend themselves to incremental drilling and which represent the majority of fields currently financed in the North American market (hence need, as described above, for the APOD in Mezzanine loans used to finance PUD's). Offshore fields which represent the majority of fields financed in the International RBL market by contrast have more certainty of timing and commitment to develop undeveloped reserves due to the commitment of the co-venturers and the relevant government agencies to the field development plan. The issues surrounding the certainty of development commitment and timing have in fact been acknowledged by recent revisions to SEC proved reserve guidelines which now require PUD classifications to be applied only to reserves that will be drilled in a defined time frame: "for undeveloped reserves, there must be an adopted development plan indicating that well(s) on such undrilled locations are scheduled to be drilled within 5 years, unless specific circumstances justify a longer time."

The "risk weighting"/adjustment approach that the US bank market takes to the company's reserve base applies also to CAPEX. When PUD's are restricted to 20% of the NPV calculation the CAPEX included will also be restricted to 20%. This reflects the overall philosophy of the approach to borrowing base calculations in the US where the analysis is more focused on the collateral value of the assets in the event they have to be sold to repay the debt rather than attempting to reflect a quasi "business" or "development" plan of the borrower's projects.

In the International RBF market, it has long been the tradition for borrowing base calculations to take account of both proved and, if there is a portfolio of fields, probable reserves. Proved reserves are included in the valuation in the case of a loan involving undeveloped fields or fields that do not have a continuous production history, and probable reserves are included in the case of a loan involving groups of producing fields or fields which have a satisfactory production history. Sometimes this convention is specifically set out in the loan documentation. Where this is the case, it is not uncommon for the international lenders also to be entitled to "risk" or adjust the reserves for the purposes of the "Banking Case". In any event, independent exploration and production companies not listed in the US are not constrained by SEC reporting criteria and tend to use probabilistic reserve assessments to evaluate projects — particularly offshore projects. Under these criteria P90 (reserves with 90% or better probability of being extracted and P50 (mid case or expected case reserves which have a 50% chance of being met or exceeded) are often used when the company assesses the internal rate of return of its project investment. In most cases the P50 roughly equates to the 2P or proved and probable reserve and the P90 to the proved or 1P case. Many reserve classification criteria and industry forums have been put in place to address the interrelationship between SEC and other reserve reporting protocols and to bridge the gap between deterministic reserve assessment and probabilistic. The most recent is the SPE PRMS initiative which seeks to ensure maximum commonality to reserve classifications (so that "Proved" equates to P90 and 1P and "Proved plus Probable" equates to P50 and 2P). In the international market 1P reserves are, for the most part, used interchangeably with P90 and 2P reserves are used interchangeably with P50.

The Banking Case and Assumption Determination

In the International RBF market, the central tool for regulating debt sizing, drawdowns, repayments, certain defaults and sometimes other matters too (such as the ability for borrowers to withdraw excess cash from project accounts) is the Projection or Banking Case. An agreed model ( excel spreadsheet based) is established between the borrower and the arranging banks at the time the facility is negotiated. Often documentation recognizes a specific role of a "Modelling Bank" who, together with the Borrower, will be responsible for building the model that generates the Banking Cases and operating the model during the life of the facility. While the Banking Case will generally be re-run twice a year, and assumption inputs such as hydrocarbon prices and production profiles, etc. will be reset each time the Banking Case is re-run, the model itself will typically not change unless it needs updating (such as when fields are disposed of or new ones are added).

The Banking Case in the international market is more of a business plan / project execution model than a pure collateral valuation. For example, while P90 reserves may be used for a single field development all of the expected CAPEX including contingency will be included. This contrasts with the "risk weighting" approach of the US collateral valuation focused approach to NPV. While the Banking Case will be conservative compared to the company's view of the world, it will nonetheless seek to reflect the business plan although under "banking" assumptions. Facility documentation will describe in detail the process for agreeing assumptions that are put into the model and how they are arrived at if the borrower and the banks fail to reach an agreement (typically the Technical Bank or Majority Lenders will determine disputed assumptions though sometimes provision is made for technical assumptions in dispute to be determined by an independent expert). Borrowers will typically seek to reduce the scope for lenders to have absolute discretion in setting disputed assumptions by insisting that the loan documentation require the Technical Bank and Lenders to act "reasonably" in assumption setting.

Sometimes borrowers are successful in getting banks to agree that assumptions used will be "consistent with" or "no less favorable" that the assumptions used by the Technical Bank/Lenders in other similar facilities (typically though this relates to economic assumptions such as hydrocarbon prices or discount rates as reserves will vary with the field specific context). Because there is an agreed model and the assumptions that go into it are carefully tested by the Technical Bank, individual syndicate banks do not typically have their own separate models but agree one single model and banking case at each review.

In International RBL facilities, the agreement or determination of assumptions (coupled with pre-agreed cover ratios, as to which see below) drives the new Banking Case and a new Borrowing Base Amount. Each new Borrowing Base Amount may be higher or lower than the previous Borrowing Base Amount (though it may never of course exceed the aggregate lender Commitments) and it is automatically derived from the new Banking Case. There is no further or specific right of approval for lenders over increases in the Borrowing Base Amount. All banking cases in the international market are on a post-tax basis, tax offset only being assumed to the degree that committed spending (CAPEX) and therefore related tax allowances push out the tax payment horizon. As the real actual oil price and therefore profits of companies tend to be higher than the Banking Case the rate at which tax allowances are cannibalised is often faster than modelled in the Banking Case. Accordingly, the tax loss carry forward has to be updated at each review also. Through the assumption setting process an individual lender can be voted into an increased Borrowing Base Amount (and consequent obligation to increase its funding subject to a maximum of its individual commitment.)

The approach in US RBL facilities is very different. There is no Modelling Bank and no Technical Bank although in US RBL facilities the Administrative Agent in effect fulfills the role of a Technical Bank. While the Administrative Agent will, using its own model, propose a new Borrowing Base Amount to the syndicate in connection with each Banking Case redetermination, each syndicate bank will run its own assumptions using its own model and decide if it wishes to approve the new Borrowing Base Amount proposed by the Administrative Agent. If the Administrative Agent proposes an increase in the Borrowing Base Amount, this must be approved by all lenders.2 If the Administrative Agent proposes a decrease in the Borrowing Base Amount this must be approved by a "Required Quorum" of lenders (typically 66 and 2/3 % of lenders by Commitment). If the Required Quorum of lenders does not approve the new Borrowing Base Amount, the Administrative Agent must poll the bank group to establish the highest Borrowing Base Amount that would be acceptable to the Required Quorum. The entire process is highly discretionary for the lenders. While in practice individual lenders when they run their individual models tend to arrive at or very close to the same result, from a strict legal point of view the borrower has no control or "come back" over what new Borrowing Base Amount may be set when a new redetermination is run. It is this particular feature of US RBLs that attracted negative commentary from Standard & Poor's in their May 2012 article on the US RBL Market entitled "Unique Features in Oil and Gas Reserve-Based Lending Facilities Can Increase Companies' Default Risk". Standard & Poor's comments "We believe the volatile nature of oil and gas prices combined with RBL lenders' unilateral discretion to change the assumptions that go into a company's reserves valuation can limit a borrower's ability to access those funds, especially during a period of stress. As a result, we view RBL facilities as a weaker form of liquidity than traditional asset-based lending facilities. We believe that companies' overreliance on these facilities creates a vulnerability, particularly for companies whose creditworthiness is already weak."

In addition, US RBL facilities are run on a pre-tax basis (apart from field level taxes and royalties) as the assumption is that continued reinvestment offsets a corporate tax burden. Finally the legal obligation of each bank is limited to its share of the borrowing base (which needs a 100 % vote to increase, but see footnote 2) rather than the nominal Facility amount.

While it is undoubtedly the case that International RBL documentation gives the lenders less discretion over assumption setting and provides a range of controls and protections for borrowers against arbitrary decision making by lenders, it is worth noting in passing that the price deck used by lenders in US RBLs tends to be closer to the actual market forward curve than in the case of International RBLs (so, in this respect, International RBLs already have built in an additional layer of protection for lenders).

In Part 3 of this series, the authors will examine debt sizing and cover ratios, loan facility covenant packages, and hedging.

About the authors

Jason Fox is a partner with Bracewell & Giuliani in London. He has over 25 years' experience advising on upstream debt financing and has advised on over 100 RBL financings.

Dewey Gonsoulin is a partner with Bracewell & Giuliani in Houston. He has over 22 years of experience advising on upstream debt financings.

Kevin Price is managing director with Société Générale Corporate & Investment Banking in London and is their Global Head of Reserve Based Finance. He is responsible for all of the bank's reserve based finance activities both internationally and throughout North America. Price has over 25 years' experience in the upstream oil and gas and financing industries. He started his career as a petroleum geologist and spent 12 years working in the oil industry for independents and majors before moving into upstream finance.

1There have been a few facilities mainly in the Middle East with longer tenors but 7 years is the maximum in the majority of the market. There are various reasons for this but bank pricing and return models are a factor.

2Some facilities allow a 90% pass mark for increases however no bank can be forced to fund its share of any increase so an increase in the borrowing base passed by a 90% vote would depend on other banks picking up the shortfall from the dissenting banks.