The Oil Market–1: Past, present, and near term

The high price of oil has become a dominant subject of interest not only for the international oil business but also for the global economy and the economies of most countries. With the price of West Texas Intermediate crude oil on the New York Mercantile Exchange having exceeded $55/bbl last year and remaining above $40/bbl so far this year, the interest is not surprising.

The oil price rise has been compared with the "oil price shocks" of 1973, 1979-80, and 1990. This article attempts to put this comparison into perspective, examine the technical fundamentals, and project current trends into the short-term future. A subsequent article will examine other market dimensions, such as politics, and suggest possibilities for the longer term.

The present market

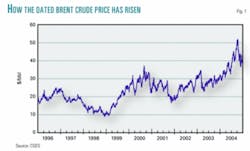

A profile of the price of oil for the last few years appears in Fig. 1. It is clear that the oil price has generally been rising since early 2002, despite the recent relapse, but more consistently so since spring 2003 and more steeply in July-October 2004. This gradual rise in price is different from the sudden jumps that occurred in the oil price shocks.

Those shocks were caused by sudden disruptions of oil supplies brought about by the Arab oil embargo at the time of the Arab-Israeli war (October 1973), Iran's Islamic Revolution (1979), former Iraqi President Saddam Hussein's attack on Iran (1980), and Saddam's invasion of Kuwait (1990) and the military operations of Desert Storm (1991) for liberating Kuwait. The main reason for the present oil price rise has been the healthy and strong demand for oil in 2003-04 brought about by economic recovery in many parts of the world, in particular China and the US.

Oil demand

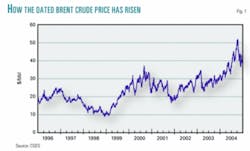

For some years, the annual increase in world oil demand was a few hundred thousand barrels per day. As shown in Fig. 2, the annual increments were 600,000 b/d in 2002, 700,000 b/d in 2001, and 600,000 b/d in 2000. The market had apparently accepted that sluggish demand growth was to be a long-lasting trend.

Moreover, the market had become accustomed to an increase in supply from areas outside the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries of about 1 million b/d/year and expected that the annual increase in supply would be greater than the increase in demand. OPEC thus had been reducing its production in order to avoid a decrease or collapse of the price of oil. By reducing their production, the OPEC countries and particularly Saudi Arabia were left with a growing volume of unwanted production capacity.

Many analysts assumed a continuation of these trends. Some had been forecasting that the squeezing market share and production of OPEC would lead to the organization's demise. The expectations were that the lowering of OPEC ceilings and decreasing production quotas for individual countries would inevitably lead to the breakdown of production discipline, growing overproduction by the member countries, and, finally, the disruption of OPEC.

Contradicting the forecasts, world demand grew by 1.8 million b/d in 2003 and an estimated 2.7 million b/d in 2004. More importantly, it took some time before this impressive increase was recognized. This was because the gathering and dissemination of information from different parts of the world involve delays and varied standards of accuracy. The earlier data are often provisional and subsequently revised. The revision might occur on a number of occasions and sometimes even a few years later. Therefore, different interpretations of the data are not unusual, particularly in the first few months and even a year or so later.

The monthly Oil Market Report published by the International Energy Agency in Paris illustrates some of these problems. The agency compiles and publishes the most comprehensive global oil data. In 2003 and 2004 IEA applied several revisions increasing estimated annual growth in world oil demand for 2003. In total, estimated demand growth for 2003 changed from the 1 million b/d projected in July 2003 to 1.8 million b/d in July 2004. Similarly, the agency's estimate for 2004 growth in world oil demand was revised up several times from 1 million b/d to 2.7 million b/d in its monthly publications between November 2003 and December 2004. Further revision is possible.

That the revival of world oil demand growth took many analysts by surprise demonstrates the difficulties inherent in global oil analysis. In its August 2004 Oil Market Report, IEA published a major revision of historic worldwide oil demand data.

Supply growth

Annual growth in oil supply from non-OPEC areas (about 1 million b/d) was insufficient to meet the unusually large annual growth in oil demand in 2003 and 2004. In response to growing demand, OPEC (particularly Saudi Arabia) last year increased its oil production and exports by utilizing unused capacity.

The concern in the market was that OPEC had not increased its production sufficiently to meet the increase in world oil demand and that the organization would not increase it sufficiently or quickly enough to meet demand in coming months. There was also a more serious concern that the size of OPEC spare oil production capacity might not be sufficient even if the organization wanted to increase its production and exports.

In the final quarter of 2004, fears about immediately available supply generally eased. Supply from OPEC increased each month from May through October (totaling 1.8 million b/d), and non-OPEC supply increased by an estimated average of 1.1 million b/d through the year. Oil prices reached their highest levels of the year in October. On Dec. 10, OPEC officials meeting in Cairo reacted to falling prices and rising inventories by agreeing to trim group production to the 27 million b/d quota that had taken effect Nov. 1.

Tight market

Despite the apparent relaxation of recent months, the global oil market remains relatively tight. More importantly, the level of oil inventories around the world is low. While inventories of crude oil have climbed back into normal ranges in volumetric terms, product inventories remain low. This follows developments in the world oil market in the last few years and in the world oil industry since the early 1990s.

In the last few years OPEC has been careful not to oversupply the market. In particular, following the collapse of the price of oil in 1998-99, the organization's aim has been to prevent an unbridled increase in global oil stocks. In this effort the group has been helped by shareholder pressure on managers of private oil companies. Forced to concentrate on the short-term performance of their companies' stock, managers reduce costs in every way possible to increase immediate profits. One cost-cutting strategy is to keep inventories as low as possible, lowering both working capital and the costs of maintaining stocks. Analysts in 2004 had been giving serious consideration to the 1990s trend of inventory reduction. Some were even discussing the pros and cons of "zero stock" oil companies.

In brief, the market fundamentals indicate a tight supply-demand balance, reduced level of global oil inventories, and decreasing OPEC spare production capacity. They imply a diminishing back-up supply and less reassurance for the global oil industry operations and oil market trade.

Fear of shortage

Despite tight balances, oil supplies have been sufficient to meet world demand. The market, however, has remained fearful of a possible shortage of crude oil or petroleum products.

Transitory factors have also influenced the market. For example, seasonal variations have accentuated market anxiety. During the spring of 2004 (as in previous years), there was fear of a shortage of gasoline at the start of summer driving season in the Northern Hemisphere, especially in the US. Since midsummer 2004, there has been fear of a shortage of middle distillates and heating oil at the start of winter. Gasoline shortages did not occur, and heating oil shortages have not been evident so far this winter.

Refineries are running at maximum capacity, and their output will be sufficient especially if the winter in the Northern Hemisphere remains mild. Nevertheless, the fear of shortage persists in the global oil market.

Market fear is aggravated by bombing, terrorism, social strife, oil company and government disagreements, domestic and global politics, and other events in different parts of the world. Sources of fear include:

Uncertainty and price

In a market raising questions like these, oil consumers have become too anxious about supply and are prepared to pay premiums in the physical and futures markets to satisfy their requirements. Obviously, their anxiety has contributed to the increase in the price of oil.

In addition, noncommercial funds, speculators, and even pension funds have entered the oil market. With the lackluster performance of the stock market, fund managers have been investing in commodities, including oil. Their activity has elevated oil prices and contributed to market volatility. When market fundamentals or investment strategies change, the exit of these funds from the oil market will accelerate the price decline.

The role of large investment funds in the oil market is a subject of debate. Another view is that the funds take the risk, provide liquidity, and are necessary as counterpart to the refiners, airlines, and others who might wish to hedge against the vagaries of the world oil market.

Nonfundamental factors

Another important feature of the oil market is that it reacts to news before any actual change occurs in physical conditions of oil supply and demand. For example, any disruption of oil exports in the Persian Gulf would be observed in the form of changes in oil deliveries—about 1 month later in Northwest Europe and 2 months later in the US. Yet the market's reaction to the news of a possible disruption is almost instantaneous, even before the disruption actually occurs.

Similarly, a forecast of a cold winter causes a reaction in the oil market long before the arrival of winter. Anticipation, perception, and sentiment play an increasing role in the oil market, as indeed they play in the stock market. With the tight oil market conditions, any news from Iraq, Russia, Venezuela, and other areas important to supply causes a reaction in the price of oil.

It is difficult to quantify the influence of nonfundamental factors in a rise in the price of oil. The definition of such factors is itself vague. Numerous parameters are involved, and many have feedback effects on each other. Their identification is extremely difficult. Estimates of their effect on price vary from few dollars to more than $10/bbl.

Capacity issues

Criticism leveled at OPEC countries for present market conditions and for not having expanded production capacity in the past few years is ironic. In order to defend the price of oil, OPEC drastically reduced its production in the early 1980s and was left with 15 million b/d of idle production capacity (Fig. 3). More recently, between 2000 and 2002, OPEC reduced its production by 2 million b/d. Most importantly, until late 2003 and even in early 2004, the general expectation was for low demand growth, greater growth in non-OPEC production, and continuation of the squeeze on OPEC in the coming years.

The world oil market apparently wishes for 4-5 million b/d of spare oil production capacity as well as large crude and oil product inventories, available around the world at all times. These conditions might have been fulfilled in the past, but they can no longer be taken for granted.

As noted earlier, private oil companies have been reducing inventories for the past decade. A large inventory is an unproductive asset that reduces profits, is expensive to maintain, and increases operating costs.

Moreover, developing and maintaining unused spare production capacity are much more costly than holding inventory. No private oil company would undertake this. The national oil companies in OPEC are also under pressure to reduce costs and become more efficient. They are less inclined than before to invest heavily in capacity to be used only as a buffer against vagaries of the international oil market.

Large spare oil production capacities can no longer be taken for granted. They require public policy decisions in the producing countries and a justification for their high costs.

Short-term oil market

Although conditions in the oil market remain generally tight, the outlook is not worrying. Supply and demand fundamentals suggest a calming of the market in coming months unless a serious flare-up occurs in Iraq, Nigeria, Russia, or elsewhere.

Oil demand growth is subsiding due to a slowdown in economic growth. In both the US and China, last year's demand-growth leaders, economies were growing less robustly at the end of 2004 than they did at the beginning of the year in trends likely to continue through 2005.

A slowdown in global manufacturing activity was also observed in August last year. This appeared more like a synchronized slowdown in all leading economies of the world. Because of the high price of oil, governments in different parts of the world introduced regulations for restricting oil and energy consumption.

On the supply side, further increases are expected in 2005 in production from non-OPEC areas. Some observers have expressed concern that international oil companies have been slow to increase their exploration and production expenditure. This is true when compared with the large increase in their revenue from the high price of oil, but in absolute terms, they have been increasing their spending, and non-OPEC production will rise. More importantly, the high-price regime is encouraging exploration and production in high-risk and high-cost areas, though the resulting production will be slow to reach the market.

OPEC production

The fear of limited OPEC production and capacity is not justified. OPEC has been producing above its own ceiling for several years (Fig. 4). Overproduction increased in middle quarters of 2004, when the market needed the oil. OPEC production in this period exceeded the group quota set in April 2004 by 2-3 million b/d and the July quota by 1-2 million b/d. The group did not begin discussing production cuts until global inventories of crude oil increased in the year's final quarter.

Furthermore, production capacities of key OPEC members are growing. In particular, Saudi Arabia's capacity approached 11 million b/d at the end of 2004.

Prospects have improved for political stability and a resumption of production growth in Venezuela, where President Hugo Chávez solidified his position in a referendum last year. Further increases in OPEC production and production capacity are expected this year.

The short-term outlook thus includes more stability than has prevailed in the oil market in the last few years if there are no surprise disruptions to supply. The longer-term outlook depends on trends in the market fundamentals that have begun to adjust to the recent period of volatility and elevated price. The second and concluding article in this series will examine them.

The author

Manouchehr Takin is senior petroleum upstream analyst with the Centre for Global Energy Studies. He worked for 9 years as senior officer in the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries Secretariat analyzing global energy and oil markets. Before that, he worked with National Iranian Oil Co., Ultramar Ltd., Amoco International, the Iranian Oil Consortium, and other oil companies. Takin holds a BS in geology from Manchester University, UK, an MBA from the Industrial Management Institute, Iran, and a PhD in geophysics from Cambridge University, UK.

Based on a presentation at the ENAEP seminar Aug. 18, 2004, in Quito, Ecuador, with data and discussion updated where possible. The views are the author's and do not necessarily reflect positions of CGES.