In a recent article in Oil & Gas Journal, author Andrew McKillop claims that higher oil prices are beneficial to the world economy.1 He labels his views as being counterintuitive. We argue here that this view is just plain wrong.

The standard view, which emphasizes that oil price shocks are bad news for nonoil exporters, is clearly the opposite of McKillop's view that higher oil prices benefit the world economy.

Our view is much closer to the standard view—which is briefly set out in this article—than McKillop's. The reasons follow here:

Point of view wrong

McKillop makes a number of assertions and observations that are repeated below. There are a number of other, extraneous comments in McKillop's article, but these are not dealt with.

Observations lead McKillop to conclude that sharply rising oil and gas prices increase economic growth rates. For example, during 1975-79, with oil prices in today's prices at $38-55/bbl, most countries in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development achieved growth rates of about 3.75%/year.

McKillop's view starts from the observation that high oil prices and rapid gross domestic product growth can coincide. He attributes this to high oil prices causing high growth. Yet correlation does not indicate causation.

It is more plausible to believe that oil prices are high because a fast-growing world economy (or expectations thereof) raises the world demand for oil. In this situation, the depressing effects of high oil prices—falling GDP and rising inflation and unemployment—are masked by growth, and inflation is exacerbated by it. Causation flows from strong demand to high oil prices, and therefore, inferring that high prices can boost world activity is wrong. What McKillop would have to do is distinguish between high prices caused by strong demand and high prices caused by supply constraints. McKillop makes little attempt to do this.

Although McKillop points out that the OECD achieved growth during 1975-79 of 3.75%/year, it should be noted that this is well below the growth rates achieved in 1961-73 of 5.5%/year. In fact, 1974 and 1975 recorded the lowest consecutive annual growth rates since figures began in 1961, with an average growth rate of just 0.9% year-on-year. The slow growth after the 1973-74 oil price shock is consistent with the standard view, not McKillop's.

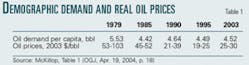

McKillop also asserts that there have been four oil price shocks since 1973 but that none of these "had an immediate, large impact on demographic demand [oil demand per capita]."

This assertion hinges on the word "immediate." No economist, policy advisor, or even politician expects the economy to react immediately to changes in the economic environment. Lags in reaction to changes in the economic environment are an important part of all economies. Once this is acknowledged, it is clear from McKillop's Table 1 (replicated in part in Table 1 here) that the very high real price of oil in 1979 subsequently led to significantly reduced demographic demand. Moreover, his data for 1985 also show that high oil prices below his $75-100/bbl estimate also reduced demand.

McKillop also claims that higher oil prices, at least up to $75-100/bbl, will result in a fall in world oil demand and are "doomed to failure" because high oil prices lead to higher demand for oil. McKillop labels this a "reverse elasticity," which is wrong.

For this to be correct higher prices would have to lead to higher demand for oil without other factors changing. Economists know this as the Giffen paradox but have yet to provide conclusive evidence that the theoretical possibility exists in practice. If McKillop could show oil is a "Giffen good," this would be a revelation. Unfortunately, McKillop's argument rests upon a transfer of resources rather than a price effect, and his "reverse elasticity" is a simple distributional effect because of the alleged differences in the propensities to consume.

In essence, McKillop argues the following:

Higher oil prices stimulate the non-OECD world economy and then stimulate growth inside the OECD. Rapidly rising oil prices raise the prices of commodities, and this enables commodity-exporting countries to raise their consumption of imports from both other non-OECD countries and OECD countries. Increases in activity raise the demand for oil, and the process iterates in a Keynesian-multiplier fashion leading to higher world GDP.

The heart of the argument is that higher oil prices raise the prices of substitute fuels and other commodities, in turn raising the spending power of these countries, and the world's GDP grows through a Keynesian spending multiplier. McKillop's view ignores the negative effect on oil importing countries, which is highlighted in the standard view set forth here later, merely saying that the propensity to consume in commodity exporters is higher than in the oil importing countries.

These central themes are simply incorrect. Using The Economist "all-items" index in US dollars as a measure of commodity prices, we find that this is negatively correlated with oil prices measured by the average of the Arab Light and Arab Heavy oil prices. What this means is that nonoil commodity exporters also see their terms of trade worsen when oil prices rise and the same effects as described in the standard view impact them.

Furthermore, there is no evidence to suggest that the propensity to spend of oil exporters is higher than the propensity to spend of oil importers. The International Monetary Fund estimates that only about a third of the additional revenues is spent by oil producers in the first year of rising oil prices, rising to three fourths after 3 years.2 This produces a negative Keynesian-multiplier effect on the world economy. These comments point to the uncomfortable truth: Poor commodity producing countries without net oil exports are hurt by rising real oil prices.

McKillop also contends that higher oil prices help poorer countries to develop oil, gas, and coal resources; without higher oil prices, the funds to develop these resources will not be available.

Higher oil prices will not help poorer countries develop oil, gas, and coal resources if, in the short term, they are paying more for their oil imports. Indeed, higher oil prices, by raising interest rates to offset inflation, might hinder development of these energy sources. In fact, McKillop ignores the role of the world's capital markets in making resources available for economic development and, consequently, a rise in oil prices is not a necessary prerequisite for investment in new oil fields.

Standard point of view

Oil price shocks constitute a commodity supply shock by raising the cost of an input into the production function. Producers respond by reducing their output, perhaps by taking unprofitable equipment out of production, and by raising their prices to cover their extra costs. With a lower level of capital being available, the productivity of workers suffers and real wage growth slows. Consequently, the demand for labor is adversely affected, raising unemployment.

An oil price shock represents a shift in purchasing power from oil importing to oil exporting countries. In order for the increased cost of oil imports to be met, a country's net exports have to rise. One way that this can be achieved is by reducing consumption in the oil importing countries. Thus, the oil shock also constitutes an aggregate demand response that may reduce GDP growth in the oil importing country.

The decline in aggregate demand will be partly offset by rising exports to oil exporting countries, not only through the income effect but also because the exchange rate may depreciate, making oil-importing countries' exports cheaper. Reduced aggregate demand may also lower interest rates, and this may stimulate interest-sensitive components of aggregate demand.

These responses can be muted and the mix between price and GDP responses changed by the fiscal and monetary authorities in each country. In particular, countries with high taxes on petroleum products will suffer smaller effects than those with low taxes. The more aggressive the monetary policy is in reaction to higher inflation, the greater will be the decline in GDP.

These effects may be exacerbated by uncertainty, expectations, and financial factors. A high oil price may be thought of as being temporary; it may be beneficial for companies to delay investment until they can be sure whether energy-intensive investment or lower energy-intensity investment is optimal. This uncertainty effect, which reduces investment, would also occur if oil prices were low but expected to rise. Thus, the effects of changing oil prices may not be symmetrical.

Likewise, consumers may run down savings or borrow in order to maintain consumption if the oil price rise is regarded as being temporary. Low oil prices may not, however, induce higher savings or the repayment of debt. If the revenues of oil producing countries flow to governments that do not let it trickle down to their populace but rather directly invest the revenue overseas, then the effect on export demand will be muted. The speed at which such investments can be reversed may also be asymmetrical if, for example, they have undertaken direct foreign investment where purchasers need to be found.

The response of the price level is crucial. If all domestic prices rise by the same percentage as the oil price shock, there is no aggregate supply shock because in real terms nothing has changed. Similarly, there is no aggregate demand shock, as there is no need to restrain domestic demand to pay for the extra cost of oil imports because the terms of trade will be unaffected. Such adjustments may well be protracted, especially as nominal wages are regarded as being sticky downwards. As nominal wages are regarded as being free to move upwards (which helps raise real wages when oil prices fall), this too may produce an asymmetry in response.

Consequently, falling oil prices may not generate as much of an output gain as a similar rise in prices causes an output loss. However, in the long run, changes in nominal oil prices have no effect unless real oil prices are permanently changed.

How much oil price pain?

The answer to the question, How much will high oil prices hurt? depends on how high oil prices rise, how long they rise for, and which country is examined.

The IMF study previously cited provides the following estimates of a $5/bbl increase (20%) in the oil price.

The rise in oil prices leads to a loss of GDP over a protracted period. Moreover, although the losses in the developing countries are initially smaller than in industrialized countries, the real impact on the poorest countries is masked by the presence of oil exporters within this category.

IMF estimates that, for the 29 most heavily indebted poor countries (HIPC), the loss of GDP in the first year after the simulated 20% oil price rise will exceed the 0.1% fall shown in Table 2 for 28 of these countries. The average decline in GDP will be 0.8%, and for Laos the decline would be 2.2% in the first year of the simulation.

Observations

High oil prices hurt the world economy's GDP growth.

While GDP is not a complete measure of welfare—it misses out environmental costs, for example—slower growth, especially in the HIPCs, is not to be welcomed.

A stronger case may have been made that high oil prices are good for the world's welfare if McKillop had highlighted the environmental costs of hydrocarbon fuel use.

Does this mean that a very low price is good for the world economy? Again, ignoring the environmental impacts, the answer is: Yes, in aggregate, the world's GDP will be greater even if the effects on GDP are smaller due to asymmetry effects.

There would be losers, of course, including the members of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries, but in principle at least they can be compensated for their losses through transfers from the increase in the world's GDP.

In particular, low oil prices would have significant benefits for HIPCs and, given the predicament of these countries, a rise in their GDP would have to be a welcome development.

References

1. McKillop, A., "A counterintuitive notion: economic growth bolstered by high oil prices, strong demand," OGJ, Apr. 19, 2004, pp. 18-24.

2. "The Impact of Higher Oil Prices on the Global Economy," IMF Research Department, December 2000, www.imf. org/external/pubs/ft/oil/2000/.

The author

Don Egginton is chief economist of the Daiwa Institute of Research Europe Ltd., London. Prior to that he worked as an economist at the TSB Group and the Bank of England.