COMMENT: US production of refined products entering new era

Ben Montalbano

Energy Policy Research Foundation Inc.

Washington, DC

Rising US production of unconventional oil and gas, alongside steadily growing Canadian oil sands shipments to US refiners, provides the US economy with the potential for a sustained renaissance in the production of refined petroleum products.

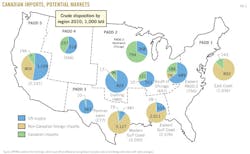

As early as 2016, according to a study released last month from the Energy Policy Research Foundation Inc., Washington, combined US and Canadian oil production, largely from technological advances in developing new unconventional resources, will likely raise North American liquids output by 3 million b/d more than 2011 levels. Waterborne crude oil imports into North America will likely fall to 4 million b/d by 2016.

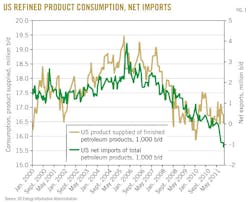

The upstream production gains provide an opportunity for stable earnings for US refiners and higher production of the entire range of petroleum products, including gasoline, jet fuel, diesel, and the large array of products produced from crude oil and NGLs. In the US Gulf Coast, the leading edge of this renaissance has already arrived, and in 2011 the US became a net exporter of refined petroleum products.

US Gulf Coast refiners shipped more than 3 million b/d of refined products to world markets as far as Brazil and Europe in October 2011.1 Although US East and West Coast markets continue to import refined products, the rising shipments from Gulf Coast refiners moved the US into a position as a net exporter of 1 million b/d of finished petroleum products.

Several forces are at play to support rising production of petroleum products. Among the more important are access to higher volumes and competitively priced North American oil production, a reduction in refinery fuel costs as a result of the shale gas boom, and access to growing markets in Latin America.

US gas boom

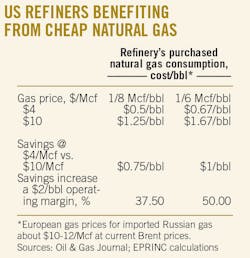

Although natural gas is often viewed as a key feedstock for the petrochemical industry, it also plays a critical role as a refinery fuel. Now, US refiners need no longer take refinery fuel entirely from the crude stream but have a lower cost alternative in natural gas.

In January 2012, natural gas spot prices dropped to less than $2.50/MMbtu for only the second time since 2000.2 Purchased natural gas often comprises at least 25% of a refinery's fuel input, and lower natural gas prices reduce operating costs and increase margins in a business known for stiff competition and low margins.3 Outside the Middle East, most international refining centers face considerably higher fuel costs.

The US has the largest and most complex refining sector in the world.4 For the many US refiners that have made multibillion-dollar capital investments in upgrading capacity, this size and complexity give them the ability to process lower priced heavy crude oils and produce a product slate commensurate with a less complex refinery running more expensive lighter crude.

PADD: US Petroleum Administration for Defense Districts*PAD District 1 (East Coast) consists of three subdistricts: • Subdistrict 1A (New England): Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, Vermont. • Subdistrict 1B (central Atlantic): Delaware, District of Columbia, Maryland, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania. • Subdistrict 1C (lower Atlantic): Florida, Georgia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Virginia, West Virginia. PAD District 2 (Midwest): Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Michigan, Minne- sota, Missouri, Nebraska, North Dakota, South Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, Tennessee, Wisconsin. PAD District 3 (Gulf Coast): Alabama, Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, New Mexico, Texas. PAD District 4 (Rocky Mountain): Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Utah, Wyoming. PAD District 5 (West Coast): Alaska, Arizona, California, Hawaii, Nevada, Oregon, Washington. *PADDs were delineated during World War II to facilitate oil allocation. |

Increasing production from Canadian oil sands provides such refineries with the heavy crude oils well matched to their complexity.

Meanwhile, shale oil from the Williston basin (Bakken), Eagle Ford, and several other emerging domestic unconventional oil plays are providing less complex refineries with access to light sweet crude oils, replacing imported crude from Africa.

Regional disparities

There are also important regional disparities in the US refining industry.

A 2009 assessment from EPRINC of the impact of the Waxman-Markey cap-and-trade bill on the US refining sector evaluated the severe low-margin environment faced by some US refiners and concluded that without substantial changes in US regulatory and business environments, more than 2 million b/d of US processing capacity would be idled or closed (OGJ, Nov. 23, 2009, p. 20).5

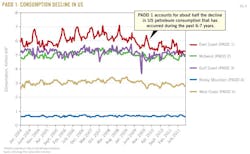

Some closures are now under way, largely in the East Coast's Petroleum Administration for Defense District 1, which faces the loss of 700,000 b/d of capacity by yearend 2012 from 2008 levels. About half of that 700,000 b/d is already idle. In addition, Hovensa LLC, a joint venture of Hess Corp. and Petroleos de Venezuela SA, announced in January it is closing its 500,000-b/d refinery at St Croix, US Virgin Islands (OGJ, Jan. 23, 2012, p. 18).

PADD 1 refineries rely almost entirely on waterborne imports of higher priced sweet light crudes and must compete with large volumes of gasoline imports from European refiners. In Europe, widespread dieselization for transportation fuels has left the continent with excess gasoline and short supplies of diesel. Large volumes of gasoline and gasoline components are routinely shipped and priced to enter PADD 1 markets.

In addition, demand for refined products in PADD 1 has declined by 1 million b/d since 2006. This accounts for about half of the nation's total petroleum demand decline during 2006-11.

These closings make for an uncertain supply outlook for PADD 1 refined products, particularly as low-sulfur heating oil specifications take effect in the northeastern US. Some supplies will be shipped from the US Gulf Coast to the Northeast via pipeline where capacity is available. Additional shipments could travel via barges from the Gulf Coast, but the availability of shipping solutions under US law is limited and will likely mean PADD 1 will have to look towards product imports from refineries operating outside the US to meet some product requirements.

There are few if any Jones Act-conforming product tankers available to ship additional refined product from US port to US port, as most conforming tankers are currently at capacity and tied into long-term contracts.

Effect of changes

Despite the low refinery margins in PADD 1, Europe has been taking the brunt of the rationalization of Atlantic Basin refining capacity. About 1 million b/d of European capacity have been closed since 2009 and another 1 million b/d are at risk of closure or sale and financial restructuring (OGJ, Dec. 5, 2011, p. 30).

European refineries are much less complex than their US counterparts and rely heavily on higher-priced waterborne deliveries of crude oil imports from Russia, Africa, and the North Sea. The recent disruption of light sweet crude supplies from Libya added to cost pressures facing European refiners.

Outside of PADD 1, most US refineries are insulated, at least partially, from the low margins that prevail among Atlantic Basin refineries. Rationalization of capacity throughout the Atlantic Basin will raise utilization rates among much of the remaining US refining fleet, and ongoing investments promise continued improvements in operations. The US refining sector also has the advantage of producing a high yield of middle distillates, such as diesel, which sell at a premium to gasoline.

Threats

Growth in global demand for middle distillates has outpaced growth for all other major refined products, and the US will remain an important supply source for products from the middle of the barrel.6 In recent years, EIA has reported US exports of distillates to world markets have ranged from 500,000 to nearly 1 million b/d.1

Although the US continues to import some gasoline blending components, in late 2009 it became a net exporter of finished gasoline. This can be attributed to reduced US demand for gasoline, strong utilization rates outside of PADD 1, and ethanol supply growth.

The American downstream renaissance is not guaranteed.

A range of existing and proposed environmental regulations and proposed changes to the tax code poses the largest threats to the competitiveness of the US refining industry. A long list of pending and proposed regulations challenges the future of the industry. How policymakers and industry adapt to these challenges will be critical in determining whether the US economy realizes the full range of security and economic benefits from expanded production of petroleum products.

Among the more important regulatory developments evaluated in the EPRINC report are the proposed Tier 3 gasoline specifications, growing and costly adoption of volumetric increases in biofuel mandates under the Renewable Fuel Standard, proposed controls on greenhouse-gas emissions, low-carbon-fuel standards, and substantial changes in the tax treatment of product inventories.

In addition to the uncertain regulatory environment, predictable and cost-effective government policies will be required so that necessary capital can be deployed to expand the transportation infrastructure needed to bring planned increases in Canadian and unconventional supplies to US refining centers as well as timely construction of refinery upgrades to process these growing supplies of North American crude oil.

References

1. Total Product Exports by Destination (Total All Countries), US Energy Information Administration monthly data: http://www.eia.gov/dnav/pet/pet_move_expc_a_EPP0_EEX_mbblpd_m.htm.

2. http://www.eia.gov/dnav/ng/hist/rngwhhdd.htm.

4. EUROPIA data: http://www.europia.com/DocShareNoFrame/docs/1/DELNCDECGOGMKBMABKJDENHMPDWD4LUJR17444U789YC/CEnet/docs/DLS/2010_EUROPIA_Annual_Report_statistics-2011-02066-01-E.pdf, OGJ Data for 2009, per the Nelson Complexity Index.

5. EPRINC Report: The American Clean Energy and Security Act: An EPRINC Assessment of Capacity and Employment Losses in the Domestic Refining Industry (http://www.eprinc.org/pdf/refiningindustry-waxmanmarkey.pdf)

6. BP Statistical Review of Energy 2011.

The author

More Oil & Gas Journal Current Issue Articles

More Oil & Gas Journal Archives Issue Articles

View Oil and Gas Articles on PennEnergy.com