Iraqis mending own pipelines

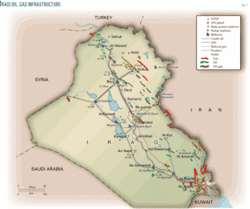

Most of the pipelines damaged during the war in Iraq are domestic crude or domestic product pipelines belonging to and repaired by the Oil Pipeline Co. (OPC) of the Ministry of Oil. OPC repair crews carried out the bulk of the work to keep oil flowing through these pipelines; extinguishing fires, cleaning up the mess, and repairing the pipelines (Fig. 1).

This article examines OPC’s organization, providing a sense of the work accomplished under extreme hardship and of the sacrifices made by people working in a small part of the Iraq oil sector.

3,000 hits

OPC successfully repaired 767 hits—damage to the pipeline such as an illegal hot tap, bullet holes, grinder holes, or explosions—on 7,200 km of pipeline during the 5 years ending May 2008 (Fig. 2). Seldom did a day pass without report of a new hit on a pipeline somewhere in Iraq. OPC prioritized and repaired these hits to keep oil flowing through pipelines in relatively less dangerous areas first, with hits in extremely dangerous locations left until security was restored.

Improved security since May 2008 has allowed OPC to access all its product pipelines and determine the total damage caused by more than 3 years of attacks and looting. OPC has identified or repaired more than 2,300 additional hits in that time and the number continues to grow as repair teams start pressure testing the lines. Explosions cause the most damage and are most difficult to repair, typically requiring replacement of one or several joints and several days’ work (Fig. 3).

All repairs before May 2008 occurred while the repair teams were under threat of attacks either directly to the workers or on the workers’ families. Pipeline repair work is dangerous even in a benign environment any place in the world. Unfortunately, 30 OPC employees died over the past 5 years while trying to do their jobs. Most of these casualties occurred as the security situation deteriorated 2004-07.

On two different occasions, OPC employees were kidnapped while on repair jobs. Their kidnappers released them but kept their equipment. Kidnappers still hold another OPC employee, having killed the passenger in his vehicle. Repair teams did not use security when responding to jobs in 2003-04 because they did not see the necessity. They quickly learned to use some type of security force for almost all jobs and refused to accept jobs in the most dangerous areas. Repair teams still require security guards from the Iraqi Army before attempting a job, but the environment is much better today and work can progress more quickly.

Difficult repairs

The highest priority and most difficult repair completed by OPC over the last few years was fixing the 14-in. OD LPG pipeline running from just south of Baghdad to the west of Baghdad and ending at the Taji LPG bottling plant north of the city. This pipeline provides more than 1,000 tonnes/day of LPG from production and import facilities in the south, crossing some of the most hostile areas near Baghdad, most notably the so-called triangle of death southwest of the city. Working in this area became very dangerous in 2004, with security continuing to decline until 2007.

Bottled LPG is the principal cooking fuel in Iraq and was in critically short supply in Baghdad 2005-08. Taji is the largest LPG bottling facility in the country, filling several thousand bottles per day. Repairing the 14-in. pipeline would allow cooking fuel to reach the people of Baghdad, improving their quality of life. Cooking fuel became so scarce in late 2006 that the black market price rose to about 10 times the official government price.

During the pipeline outage LPG trucks loaded at a facility about 1 hour south of Baghdad in Hilla drove to Taji, providing less than 25% of typical supplies. OPC operated like this for more than 2 years, before linking up with both US-led coalition forces and Iraqi Army security teams in a coordinated effort to fix and secure the line. Late-2007 repairs took about 2 weeks once security for the teams and the pipeline was established. Reopening the pipeline was a victory for OPC and its security partners in the Iraqi Army and the coalition’s Energy Fusion Cell.

Repair of the Zekerton Canal crossing close to Kirkuk in northern Iraq was also difficult. Eight product and crude oil pipelines crossed the canal in a bundle design that created an easy and high-value target. A hit on these lines in October 2005 created a horrific fire and environmental disaster. The canal provides fresh water to several local farms and residents. Repair crews spent several days trying to extinguish the fire and control the spill before starting necessary repairs. Further cleanup followed the pipeline repairs.

Another unforgettable repair job took place north of Baghdad in the Thar Thar Canal close to Samarra. This area became very dangerous in 2004 and attacks became common on the product and crude pipelines moving oil south from Bayji to Baghdad, eventually making the pipelines unusable.

Attackers hit a bundle of nine pipelines in February 2006 at an irrigation canal crossing 7 km south of Mushada depot. An explosion and heavy smoke accompanied pollution of fresh water in the canal. The military provided a strong perimeter defense while helicopters lifted repair equipment over the canal and into position to make the repairs. The canals provided a natural barrier, making it very difficult to access and repair the damaged pipe.

Next priority

The pipeline corridor from Mosul to Baghdad is the current focus of repair. Two pipelines supply natural gas and products from Bayji to Mosul. Several pipelines lie south of Bayji in the corridor between Bayji and Baghdad; supplying crude oil, natural gas, LPG, and products to Baghdad. The corridor passes several cities considered very dangerous before 2008, including Tikrit and Samarra. Many attacks occurred on these pipes between 2004 and 2008.

All repair work in the corridor stopped once the area became too dangerous and the number of hits too great. Improved security now allows OPC to perform inspections of the damaged pipelines and assess requirements to get them operational. Most of the 2,250 hits detected since May 2008 occurred in this corridor.

OPC’s first priority is repairing the 16-in. OD natural gas pipeline supplying fuel to the Taji power plant. Baghdad is short of electric power and Taji provides over 100 Mw to the Baghdad area.

Exclusion zones

Pipeline Exclusion Zones (PEZ) help secure critical pipeline corridors in the northern part of the country. PEZ are a fortified lateral zone measuring roughly 200 m across. Fortifications normally consist of a ditch, dirt mound, a fence, and roving patrols (Fig. 4).

A PEZ completed between Kirkuk and Bayji in late 2007 proved to be an important enabler for securing crude pipelines expected to export crude through Turkey. OPC and US forces are building the Bayji to Baghdad PEZ, which has already been beneficial in providing security while OPC teams work in the area. Future construction of new pipeline will also be much easier. Plans already exist for a new crude line from Bayji to Baghdad as a replacement for the two 12-in. OD pipelines built in the early 1950s.

Future objectives

As the workload for repairing pipelines decreases in the near future, other priorities will emerge. OPC has installed new meters at all its facilities over the last 2 years. It has completed most of the work, with a few crude and HFO pipelines delivering to power plants still waiting. It also has plans for a product tank data system and new pipelines to replace old and deteriorating lines now in use.

Cathodic protection has not operated for years and soil conditions in many areas are very corrosive, raising the importance of future maintenance plans. An inspection program under development will lead to regular pigging of all lines. Pigging inspection has nearly halted since 1991 because of UN sanctions and the poor security situation. Specific plans do not exist, but OPC would like to install a modern supervisory control and data acquisition (SCADA) system for the country’s product pipeline network. The current system is strictly manual.

Organization

OPC is headquartered in the Daura area of Baghdad adjacent to the Daura refinery and has offices throughout the country. It has 3,700 full time employees and another 1,300 temporary workers, operating 12 depots with 120 storage tanks, and normally has about 1 billion l. of product in its system. Kerosine has seasonal storage volume because it is the primary heating fuel in the country. The Ministry of Oil’s target inventory for kerosine on hand before winter measures about 400 million l./year.

OPC’s 7,200 km of pipeline consist of 2,800 km light products, 1,435 km LPG, 211 km heavy fuel oil, 979 km domestic crude oil, and 1,775 km natural gas. Before 2003 the pipeline network operated at a rate of 5.6 billion cu m-km of crude and products. Current utilization is about 2.4 billion cu m-km (assuming a 1,000:1 gas-to-liquid ratio).

Five Fast Repair Teams accomplished almost all emergency pipeline repairs. Each team consists of about 20 employees with proper experience and training in repairing pipelines in accordance with industry standards. They normally deploy for 15 days to camps close to the repair area before returning for a break. Their equipment consists of an excavator, shovel, crane, welding machine, and cutting machine. The continuous nature of the work makes equipment maintenance and supply difficult.

OPC’s success required courageous leadership. OPC Director Gen. Salah Aziz, reporting to Deputy Minister of Oil Mo’Tasam, has provided this leadership. Aziz was director general of North Gas Co. in March 2003. When coalition forces arrived in Kirkuk, he and his team ignored evacuation orders, continuing to sweeten the very dangerous gas in the north that has high concentrations of H2S. Pentagon prewar planners had expressed concern that Saddam Hussein might use the unsweetened gas as a weapon against US forces coming into Kirkuk. Aziz returned to Baghdad as director general of OPC in July 2003, despite personal risk to himself and his family.

The authors

Kevin Ross ([email protected]) is an oil consultant to the Multi-National Force–Iraq’s Energy Fusion Cell, Baghdad. He has also served as an oil advisor within the Oil Directorate of Iraq’s Coalition Provisional Authority, a business consultant for IBM and Pricewaterhouse- Coopers, a systems engineer for SAIC, and nuclear submarine officer in the US Navy for more than 10 years. He holds a BS in nuclear engineering from Texas A&M University (1987) and an MBA from the University of Maryland (2000).

Gary Vogler ([email protected]) is senior oil consultant to the Energy Fusion Cell. He is a graduate of the US Military Academy (1973) with 21 years’ experience at Mobil Oil and ExxonMobil, ending in early 2002. He is also a retired US Army Reserve officer. Vogler was senior oil advisor under ORHA and then deputy senior oil advisor during CPA in 2003 and 7 months into 2004. He returned to Baghdad in December 2006 as a contractor to assist with the oil reconstruction program under the Gulf Region Division of the US Army Corps of Engineers.