Federal agencies need plan to decommission gathering lines

A recent report by the US Government Accountability Office (GAO) advised that the directors of the US Department of Interior’s Bureau of Land Management (BLM), Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), and National Park Service (NPS), and the Department of Agriculture’s Forest Service should develop a documented plan to ensure the agencies collect and maintain the data necessary to oversee decommissioning of gathering lines. The directors should further specify when gathering lines should be decommissioned following the termination or revocation of rights-of-way and should analyze all overseen gathering lines to identify and prioritize those that pose the greatest safety, environmental, or fiscal risks for oversight and decommissioning.

Background

Oil and gas pipeline operators have installed at least 384,000 miles of onshore gathering pipelines across the US. Many are on federal lands and were installed decades ago.

Of the about 650 million acres of federal lands, 95% are managed by the Forest Service, BLM, FWS, or NPS. These agencies oversee most of the oil and gas operations on federal lands. Such operations include gathering line decommissioning.

Some have raised concerns about potential environmental or safety risks that gathering lines on federal lands could pose if not decommissioned properly. The GAO was asked to review issues related to decommissioning oil and gas gathering lines on federal lands.

This article examines the risks associated with gathering lines that are not decommissioned properly or in a timely manner and how agencies oversee decommissioning of gathering lines on federal lands:

- If pipeline operators do not decommission gathering lines properly or in a timely manner, they could pose various safety and environmental risks.

- It is unknown how many gathering lines are on federal lands or the extent to which operators have properly decommissioned them because agencies have limited data and have carried out limited oversight of decommissioning.

- Limited oversight can lead to orphaned gathering line, lacking identifiable responsible parties. In such cases, the federal government may have to step in to manage and pay for decommissioning.

- To strengthen federal oversight of gathering lines on federal lands, GAO recommends that agencies develop plans to improve data collection for oversight purposes, further specify decommissioning timing requirements in some cases, and identify gathering lines presenting the greatest safety, environmental, or fiscal risks to prioritize.

Locations

Agencies generally do not collect data to know the precise routes of gathering lines on federal lands. Most oil and gas development on federal lands, however, occurs in western states: about 93% of oil production from federal lands is taking place in New Mexico, Wyoming, and North Dakota. But oil and gas infrastructure can be found on federal lands across the country. For example, most gathering lines on FWS-managed refuges are in Louisiana, Texas, and Oklahoma.

Typically, a land management agency regulates:

- Gathering lines used to access federally leased mineral rights (on-lease) granted to an operator.

- The use of a federal surface to install and operate gathering lines off-lease or to access non-federally leased mineral rights (right-of-way).

- The terms of access across federally managed lands for operators to develop existing non-federal mineral rights (e.g., reserved rights or inholdings).

BLM also is responsible for granting and overseeing rights-of-way for oil and gas pipelines that traverse federal lands managed by two or more agencies (excluding NPS), even if the pipeline does not cross BLM-managed land. The Department of Transportation’s Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA), which oversees the safety of pipeline transportation, historically has not regulated most gathering lines. This is because gathering lines pose lower risks as they tend to be in less populated areas and operate at low pressures.

Over time, however, increased extraction of gas and oil from shale deposits has resulted in larger, higher-pressure gathering lines, and development has brought populated areas closer to some rural gathering lines, increasing potential safety risks. Because most gathering lines have historically not been regulated, available data about them are limited.

In 2012, GAO recommended that PHMSA collect data from operators of historically unregulated onshore gathering lines. In 2019 and 2021, PHMSA issued regulations instituting new reporting requirements for operators of historically unregulated gathering lines. Specifically, among other things, the agency required all operators of hazardous liquid gathering lines to submit annual reports containing data on pipeline characteristics, such as diameter and age, starting in 2021. PHMSA required the same of all operators of natural gas gathering lines starting in 2023.

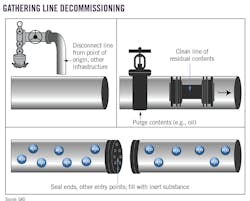

The accompanying figure illustrates some of the steps involved in decommissioning gathering lines. Above-ground gathering lines are usually removed while buried gathering lines remain in place to minimize disturbance to the surface. In either case, the land is then reclaimed. Such reclamation activities could include planting native vegetation, recontouring the soil, and taking erosion prevention measures.

Gathering lines that were not decommissioned properly or in a timely manner have led to various safety and environmental risks, including spills, emissions, and explosions. Comprehensive data on incidents associated with gathering lines do not exist, though officials GAO interviewed highlighted the following:

- Spills. The most common risk cited by interviewed officials was spills. Hydrocarbons can remain in gathering lines that were not properly decommissioned. If those pipelines degrade over time or rupture from unexpected events, such as landslides, there could be spills that can contaminate soil and water, harm wildlife, and damage plants.

- Emissions. If operators do not properly purge hydrocarbons when gathering lines are decommissioned, those pipelines can emit harmful gases such as methane. The extent of methane emissions from improperly decommissioned gathering lines on federal lands is unknown.

- Explosions. If gathering lines are not disconnected from wells, purged of product, or properly capped to prevent natural migration of product, they could leak hydrocarbons and cause an explosion if they are damaged during drilling or construction activities.

For example, on Apr. 17, 2017, about 4:45 pm local time, a single-family home in Firestone, Colo., was destroyed by an explosion. A resident and a plumber who was working at the house died in the explosion, and two other residents were injured. At the time of the explosion, the fatally injured resident and plumber were replacing a water heater in the basement.

Representatives from the Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission, the Frederick-Firestone Fire Protection District, Black Hills Energy, Anadarko Petroleum Corp., and PHMSA responded to the accident site to conduct an investigation. A National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) investigator later went to the accident site to review the initial investigative findings and support subsequent on-scene work.

Three severed pipelines were found beneath a concrete pad about 6 ft from the foundation of the house. The three lines were originally connected to natural gas wells as part of a producing field. The lines included one 1-in. OD polyethylene line and two 2-in. steel lines.

According to the NTSB report about this incident, the pipeline operator had failed to properly decommission the gathering line near the home. In addition, the homeowner was unaware of this because the local authorities had failed to confirm the location and status of nearby gathering lines before approving construction on the property.

Agency efforts

To varying degrees, agencies seek to ensure proper decommissioning through administrative oversight, obtaining financial assurances, and on-site monitoring. Agency efforts to ensure proper decommissioning, however, may be hindered by insufficient bonding, data limitations, and ambiguous requirements.

Officials from all four agencies told GAO that operators have not posted sufficient bonds to decommission all existing gathering lines, but the agencies are taking steps to address this issue. For example, both FWS and NPS updated their regulations in 2016 to require operators to provide sufficient financial assurance.

However, since FWS and NPS have not historically collected bonds for many existing gathering lines, it will take time to bring operators into compliance. In a 2021 report, BLM acknowledged that insufficient bonding levels provide an inadequate incentive for operators to decommission oil and gas infrastructure. BLM proposed new regulations in 2023 that would increase bond minimums collected for on-lease activities, and officials told us they plan to issue additional new regulations increasing bonds for rights-of-way.

Agencies do not know the number, status, and precise routes of all gathering lines on federal lands, based on GAO’s analysis of available data and interviews with agency officials. Across the four agencies, gathering line data are limited, incomplete, and can be difficult to access if only hard copy records exist. BLM has ready access to detailed data for the more than 95,000 wells on federal leases, but its databases do not include any data for the gathering lines associated with those wells. NPS and FWS databases also focus on wells. These agencies also have little to no data for the gathering lines associated with those wells.

BLM and Forest Service, which collectively manage nearly 39,000 rights-of-way with gathering lines, collect some information about those gathering lines but the data are limited. For example, neither agency tracks information on operating status (e.g., active, idle, decommissioned, etc.) or the precise routes of gathering lines.

Officials from all four agencies further told GAO that some information about gathering lines is maintained in field offices, but this information may be difficult for staff outside of those field offices to access and use for monitoring purposes. These officials also said data can be even more sparse for older gathering lines, which in some cases were installed before federal management of the land.

While PHMSA issued regulations requiring new data reporting, operators are only required to submit geospatial data representing the precise locations of a subset of gathering lines. Also, for orphaned gathering lines, there is no operator to report data.

For the nearly 39,000 gathering lines on BLM and Forest Service rights-of-way, the timing requirement for decommissioning is ambiguous, which results in a deference to operators that can affect agency oversight. BLM and Forest Service regulations specify triggers for termination and revocation of rights-of-way. However, upon termination or revocation, both agencies’ regulations direct operators to decommission “within a reasonable time.” This does not set a clear expectation of timeliness that agencies can effectively enforce.

Some agency officials told GAO that they primarily rely on operators to identify when they intend to decommission gathering lines. According to Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, agencies should define objectives in specific and measurable terms that are fully and clearly set forth so they can be easily understood. Without specific decommissioning timing requirements, BLM and Forest Service cannot ensure operators decommission gathering lines in a timely manner. If they are not decommissioned in a timely manner, gathering lines may become orphaned, with no existing party responsible if operators go out of business. This can lead to the federal government having to pay for decommissioning. With more specific decommissioning timing requirements, agencies can strengthen their oversight and mitigate the federal government’s fiscal exposure caused by orphaned gathering lines.

Agencies are taking some steps to improve limited data, but those efforts are ad hoc and not comprehensive. Examples of strategies to improve data include:

- Digitizing existing paper files. For gathering lines on federal lands that were installed decades ago, agency officials told GAO any existing information is only available on hard copy maps or surveys stored in field offices. Although digitizing these paper copies can be time- and resource-intensive, two BLM field offices told GAO that they have started to digitize this information. For example, beginning in 2009, officials from one BLM field office told GAO they undertook an extensive effort to digitize maps and aerial imagery. As a result, the field office now has geospatial data for about 90% of the gathering lines in its region, according to officials.

- Acquiring geospatial data from operators. Some agency officials in field offices told GAO they are now requiring operators to submit geospatial data when installing new gathering lines. Another agency told us it worked with operators to map existing gathering lines and provide that geospatial data. Although it took the operator nearly 10 years to map its gathering lines, FWS noted it can now use those maps to identify potential leak sources and avoid abandoned gathering lines when conducting regular maintenance activities.

- Improving existing data systems. In 2022, FWS officials told GAO they added several data fields for gathering line records to the service’s existing database. Those data fields may eventually provide staff with additional information to oversee decommissioning, such as operating status. However, officials said it will take years to fully collect the data necessary to populate those new data fields for existing gathering lines.

- Collecting geospatial data during inspections. Staff from NPS and one of BLM’s field offices told GAO they gather geospatial route data when conducting compliance inspections of gathering lines.

- Collecting data through external sources. Some agencies told GAO that they collected gathering line data from external sources. Two agencies mentioned collaborating with state regulatory agencies that collect geospatial route data. One agency purchased a subscription for proprietary data that a vendor provides for the oil and gas industry. Staff from one BLM field office also reported that they work with local organizations, such as water associations, to collect data for gathering lines.

- Identifying undocumented infrastructure. Some agencies are using funding from the 2021 Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) to identify oil and gas infrastructure not documented in their databases. For example, NPS developed a protocol for its inspectors to review existing records at state agencies and search for any evidence on park lands that might indicate improperly decommissioned infrastructure, such as complaints about water quality in the area.

These steps are likely to result in improved data over time, but they have been undertaken in an ad hoc manner and vary from field office to field office. None of the agencies has a documented plan to ensure they are collecting and maintaining the data needed to oversee decommissioning activities.

Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government call for management to use quality information to achieve the agency’s objectives. Quality information is appropriate, current, complete, accurate, accessible, and provided on a timely basis. Developing a plan with a timeline for implementing data improvement efforts would provide management the assurance that officials are collecting and maintaining the data needed to oversee decommissioning. Specifically, a documented plan would identify what data are needed, potential sources for the data, timelines to collect or acquire the data, and how best to maintain the data over time, ensuring that they remain current and accessible.

Orphaned lines

The federal government has stepped in to decommission some orphaned gathering lines. Agencies have limited resources, however, and most of the agencies have not taken actions that will be necessary to prioritize the gathering lines that pose the greatest risks. While the total number of orphaned gathering lines is unknown, implementation of the IIJA presents agencies with an opportunity to decommission the riskiest gathering lines.

Congress authorized and appropriated $250 million in funding, available through September 2030, to decommission orphaned gathering lines and other orphaned infrastructure. All four agencies have taken steps to identify orphaned gathering lines to decommission with IIJA funding.

As of September 2023, Interior had approved projects that will cost more than $82 million, including $23 million for the Forest Service. For example, in one funded project that will cost $3.1 million, the Forest Service will remove 31 miles of orphaned gathering lines in the Monongahela National Forest and reclaim the land. According to the agency, the gathering line—which contains unknown quantities of hydrocarbons—could leak or emit methane near ecologically and biologically diverse habitats that are home to endangered species. The gathering line also crosses several walking paths in the forest, and visitors have been injured when they accidentally walked on sections of the gathering line.

Agencies’ use of IIJA funding will address some orphaned infrastructure, but agencies told GAO that IIJA funding will not be sufficient to decommission all of it. For example, Forest Service officials said that even if all of the $250 million was provided solely to the Forest Service, those funds would allow for decommissioning of only 5-10% of the known and expected orphaned infrastructure on Forest Service lands.

The IIJA provides funding to decommission existing orphaned gathering lines and calls for agencies to rank those lines for priority in decommissioning. Agencies also need to analyze the risks associated with other gathering lines they oversee in order to prioritize their oversight. This is because additional lines may eventually become orphaned and some of those may pose substantial safety, environmental, or fiscal risks.

According to Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, agencies should identify, analyze, and respond to risks related to achieving the defined objectives. GAO found that only NPS has assessed the potential risks of gathering lines on its lands. When updating its regulations in 2016 and preparing an environmental impact statement, NPS analyzed risks from oil and gas operations, including gathering lines, and identified additional risk mitigations.

No other agencies have analyzed the risks associated with the gathering lines they oversee. Assessing risks would allow agencies to adequately prioritize the gathering lines that pose the greatest safety, environmental, or fiscal risks for either oversight attention if lines are active, or decommissioning if lines are orphaned.

Methodology

GAO provided a draft of the report reaching these recommendations to the Department of Interior and Department of Agriculture for review and comment. In its comments, Interior concurred with GAO’s recommendations and Agriculture generally concurred. The two

departments provided technical comments, which GAO incorporated as appropriate.

In preparing its report, GAO reviewed agency documentation and its own earlier reports and conducted a literature search for studies or reports published over the past 10 years. It used key terms to search relevant databases, such as ProQuest, SCOPUS, and Petroleum Abstracts. It also reviewed relevant laws, regulations, policies, and guidance related to decommissioning gathering lines.

GAO then compared each agency’s decommissioning oversight activities with its responsibilities outlined in regulations, policies, and standards for internal control. To collect a range of perspectives about risks and how agencies oversee decommissioning, GAO interviewed a nongeneralizable sample of 35 knowledgeable stakeholders, including agency officials from headquarters and field offices, state agency officials, representatives from the oil and gas industry, and members of environmental advocacy and pipeline safety organizations. Because GAO selected a nongeneralizable sample of organizations to interview, the information gathered is not generalizable to organizations beyond those interviewed.

GAO conducted its performance audit from January 2023 to January 2024 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards.