Central Asia's potential as Asia-Pacific oil supplier limited for years to come

The Middle East is the Asia-Pacific region's largest energy supplier, currently satisfying a demand for oil that must keep pace with the region's continued economic growth. This dependence on the Middle East has caused Asia-Pacific to join the US and other Western nations in the hunt for alternative suppliers. Central Asia, located between the Middle East and Asia-Pacific and already an oil and gas exporter, is an attractive possibility.

With energy production projected to rise rapidly over the next decade, Central Asia is poised to become a major player in the world energy market. But the landlocked region's options for transporting oil and gas to Asia-Pacific markets are limited and problematic.

Passage via pipeline east through China presents construction challenges, and south through Iran, or through India and Pakistan via Afghanistan, is fraught with political difficulties. Not until geopolitics becomes more favorable to the southbound options, or technologies make the China route possible, will Asia-Pacific be able to tap the energy resources of Central Asia.

Asia-Pacific issues

The Asia-Pacific region has long been heavily dependent on oil imports-particularly from the Middle East-to meet its energy needs. This dependence has increased since the early 1990s, when China joined the ranks of Japan, South Korea, and other Asian nations as a large and rapidly growing oil importer. At the same time, India's oil imports also rose dramatically.

With the region's own oil production stagnant and oil demand rising continuously, Asia's reliance on oil imports will reach even higher levels in the coming decades.

The region's dependence on oil imports and the dominance of the Middle East over oil supply have made energy security a concern for many Asian nations. Supply diversification is one way to address the issue, but oil importing countries in Asia have been hard-pressed to find viable alternatives to Middle Eastern oil. Now the prediction that all major countries in the region, including Indonesia and Malaysia, will be net oil importers within the next 15 years increases the urgent need to diversify.

While Asia-Pacific has sought to broaden its oil supply, Central Asia has emerged as a potential player in the world energy market. Strategically located vis-à-vis Russia, the Middle East, and Asia-Pacific and adjacent to Iran (a US adversary), Turkey (a Western ally), and Afghanistan (a war-torn country undergoing reconstruction), the geopolitical importance of Central Asia is obvious.

More importantly, Central Asia may prove to have potentially large oil and gas reserves, and its petroleum production is rising. Even before the terrorist attacks on the US on Sept. 11, 2001, the US and other Western powers were greatly interested in Central Asia, given its strategic location and oil and gas potential.

The recent conflict in Afghanistan and the role played by Central Asian nations such as Uzbekistan and Georgia-as well as by Russia-in the US-led war on terrorism have heightened Central Asia's geopolitical importance.

When considering the energy needs of the Asia-Pacific region and the potential role of Central Asia, two critical questions present themselves: Can Central Asia be a viable alternative energy supplier, and can an energy triangle be formed among Asia-Pacific, the Middle East, and Central Asia? Answering these questions requires consideration of many factors, including assessment of Central Asia's role in addressing the energy supply and security concerns of the Asia-Pacific region.

Rising oil imports

Asia-Pacific encompasses East Asia, Southeast Asia, South Asia (including Afghanistan), and Australasia (including the Pacific Islands). In 2001 the region consumed a little over 20 million b/d of oil, of which 12.6 million b/d was net imports.1

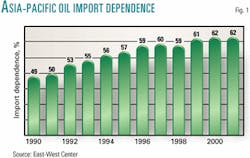

This represents an import dependence of 62%, up from 49% in 1990 (Fig. 1). Despite the 1998 financial crisis and the slowdown of regional and global economic growth in 2001 associated with high oil prices, oil demand in Asia-Pacific is poised to grow continuously over the next 15 years, albeit at rates much lower than those seen in the late 1980s and most of the 1990s. With flat regional oil production, overall oil imports-and hence import dependence-are set to rise.

A comparison of US and Asia-Pacific oil consumption and dependence highlights the seriousness of the latter's reliance on imported oil from a single source-the Middle East. Both regions have oil consumption and oil import dependence, but Asia-Pacific's consumption is slightly greater and its import dependence higher. In 2001, the US consumed 19.6 million b/d of oil with an import dependence of 54%, up from 42% in 1990.2

The Asia-Pacific region is facing a more precarious situation: More than 90% of the region's oil imports comes from the Middle East; only a quarter of US oil imports comes from the Persian Gulf. In terms of total oil consumption, the Middle East supplies well over half the amount consumed in the Asia-Pacific region compared with less than 15% in the US.

While the administration of President George W. Bush has been anxious to stabilize or reduce US dependence on oil imports (a nearly impossible task because of the steadily rising oil demand and declining oil production in the long run), pressure has been mounting for Asia-Pacific countries to follow suit and, in particular, to diversify their supply and move away from a reliance on Middle Eastern oil.

Central Asia has the energy reserve potential and is geographically closer to the Asia-Pacific than any other non-Middle East energy provider (such as Africa, the North Sea-Europe, or South America). Can Central Asia become the region's new oil supplier?

Production growth

Central Asia is defined here to include eight former Soviet Union republics that gained independence in 1991. Five are in the Caspian Sea region (Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and Turkmenistan) and the Caucasus region (Armenia and Georgia). The remaining three (Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan) are inland, with the first two bordering Xinjiang, China.

Central Asia's energy resources are concentrated in those countries surrounding the Caspian Sea. Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan together account for 92% of the region's total oil reserves. Turkmenistan has over 40% of Central Asia's total proven natural gas reserves, followed by Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan-the region's single largest natural gas producer-each at 27%. Together these three countries share 95% of Central Asia's total natural gas reserves.

Although Central Asia accounts for only 2% of the world's proven oil reserves and 5% of proven gas reserves, its potential is many times greater, particularly for natural gas. The current level of exploration in Central Asia is low-both a major obstacle to development and the reason behind Western oil companies' keen efforts to determine the region's resource potential.

Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, many of the newly independent Central Asian countries experienced economic contraction in the early 1990s. During 1992-95, oil and gas production in Central Asia declined significantly because of Russia's reduced technical and financial support. Investment from the West has since flowed into the region, helping to revive its oil and gas industries.

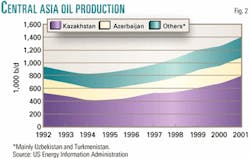

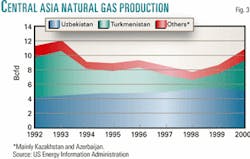

Oil production began to recover in 1996 and by 2001 was well above 1992 levels (Fig. 2). Despite a brief rebound in 1996, natural gas production continued to decline through 1998 before rising again in 1999 and 2000 (Fig. 3).

In 2001, Central Asia produced roughly 1.4 million b/d of oil, of which net exports accounted for about 57%.3 Its share of world oil production, however, is only 2%, compared with the Middle East's 28%. Central Asia's dry gas production amounted to 11 bcfd, or about 5% of the world total.4

Notwithstanding current modest levels of production, Central Asia's prospects for growth in oil and gas production are promising. Oil production in Central Asia is projected to increase to 3.4 million b/d in 2010 and nearly 4 million b/d in 2015 under the base-case scenario.5 Kazakhstan is likely to lead the way, followed by Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan.

Studies show that the region's projected output for natural gas will reach 17 bcfd in 2010 and 20 bcfd in 2015. The leaders in gas output growth will be Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan, followed by Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan. Production in other Central Asian countries will remain low; oil and gas imports will be necessary to satisfy their needs.

Export potential

Export potential is the key to determining Central Asia's importance in the global energy market. Like its economy, oil and gas consumption in Central Asia has undergone a period of adjustment.

During 1992-97, the region's oil consumption was down 40% before the positive growth resumed in 1998. In 1992, Central Asia was a net oil importer, given the limited quantities coming out of Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan. This situation reversed in 1993. In 2001, net oil exports from Central Asia surged to 850,000 b/d.

Heavy subsidies and a better-developed infrastructure derived from the Soviet Union era have stabilized natural gas consumption in Central Asia since independence. The region exported large volumes of natural gas, mostly to Russia through the old Soviet pipelines in 1992.

Because of lower gas production and stable consumption, net gas exports from Central Asia declined dramatically during 1992-98, plunging by 73%. They have since rebounded strongly; by 2000, they returned to 1992 levels, thanks to a jump in gas production in Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan.

With the projected increase in production, Central Asia's oil and gas net exports are expected to rise rapidly over the next 10-15 years. Oil exports are projected to reach about 2.5 million b/d in 2010 and 3 million b/d in 2015.6 Natural gas export availability is likely to grow to 7 bcfd in 2010 and 9 bcfd in 2015.

The export availability of Central Asia's oil is hardly comparable to that of the Middle East. In 2000, the Middle East exported 18.8 million b/d of oil, 89% of which was crude oil and 11% petroleum products.

If Asia-Pacific received all of Central Asia's oil exports, the amount would satisfy only 10% of the region's total oil demand by 2015. Currently, Central Asia's energy exports to Asia are practically nonexistent. Over the next 10-15 years, the region will export only a small fraction of its available oil and gas to Asia-Pacific. Why? The fundamental reason lies in the control and routing of oil and gas pipelines.

Although most of Central Asia falls between the Middle East and the Far East, it is a landlocked region. Pipelines are the basic means for transporting oil and gas out of the area. The economics associated with export pipeline projects and the desire to catch Asia-Pacific's fast train to economic growth are mingled with geopolitical and regional conflicts in a complex way, making any strong energy link to the Far East a dream for the next generation.

Russian influence

Russia continues to have a profound impact on Central Asia's oil and gas export routes. At the time of Russian independence in 1991, Central Asia's oil and gas pipelines, particularly those surrounding the Caspian Sea, were all Russia-bound.

The pipelined oil and gas were either passed through Russia for export or used by Russia to free up its own oil and gas for exports to the lucrative West European market. Since 1991, Russia has made a concerted effort to ensure that existing pipelines continue routing through Russia, and it has largely succeeded.

Existing oil pipelines to Russia have been repaired, upgraded, and expanded. The only operational natural gas pipeline out of Central Asia runs from Turkmenistan to Russia via Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. The gas is exported mainly to Ukraine, with small volumes going to Russia.7

Many Central Asian countries have strongly resisted routing oil and gas pipelines to Russia exclusively, not only for the sake of independence but also to avoid price and currency disputes. Faced with the complex task of broadening their markets, Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan, assisted by Western oil companies, built new pipelines to route oil to Black Sea terminals, which would ultimately provide access to markets throughout East Europe.

These new routes, however, have not bypassed Russia completely. At least two oil pipelines-one from Azerbaijan's Baku, the other from Kazakhstan's Tengiz oil field-have been routed to Russian terminals in the Black Sea. Russia will undoubtedly continue to assert its influence by persuading Central Asian countries to take advantage of the existing pipeline system.

Iran's role

Western oil companies view Central Asia as a hedge against potentially disastrous disruptions in oil exports from the politically volatile Middle East. They have tried to stay out of territorial disputes dividing the Caspian Sea and to focus instead on obtaining good commercial terms.

While US companies must be mindful of sanctions against Iran, their European counterparts are unhampered by such restrictions. Nearly every company active in the Caspian region, however, would like to see the US's unilateral sanctions lifted.

Iran has three ethnic Azeri provinces with a combined population of 25 million; oil must be transported to them from oil fields more than 1,000 miles away. Their neighbor Azerbaijan produces a great deal of oil for export but cannot supply these provinces. Instead, Azerbaijan sends its oil to Turkey to supply the Mediterranean market.

Sanctions and trade embargoes affect business, but the practical and geopolitical realities are understood by an industry that has learned to survive under difficult conditions.

Iran plays a unique role in determining the future of Central Asia as an energy supplier. Prior to 1991, Iran was the only country bordering the Caspian other than the Soviet Union. Now Iran shares borders with three newly independent Central Asian countries-Turkmenistan and Azerbaijan in the Caspian Sea region and Armenia.

Iran also is the only Middle East oil exporter and key Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries member that borders Central Asia. To gain access to the Persian Gulf-and ultimately Asia-Pacific-Central Asia must build its pipelines through Iran.

A few of these pipelines already exist, exporting Central Asia's oil to northern Iran in exchange for an equal amount of Iranian oil exports to Asia. The swap program has been operating since 1998 on a small scale between Turkmenistan and the Iranian port of Neka. A 208-mile oil pipeline between Neka and Tehran is now under construction.

TotalFinaElf SA is proposing a second pipeline between Azerbaijan and Iran. Despite the economic benefit, further route expansion through Iran is unlikely because the country's share under the swap program is limited.

Central Asia could also export its oil to the Far East through Iranian ports on the Persian Gulf, but this would not help Asia-Pacific reduce its dependence on the Middle East. Moreover, the US government has strongly objected to the proposal, making it difficult to raise the necessary capital.

Exporting Central Asia's oil and gas to Pakistan and India by pipeline through Afghanistan is a possibility, albeit a very challenging one. The India-Pakistan rivalry adds to an already complex situation.

Alternatively, Afghanistan could give Central Asian countries access to the Arabian Sea, but Afghanistan's serious lack of infrastructure would make any such plan costly.

The US position on energy-related matters in Central Asia is clear: It discourages the laying of oil and gas pipelines through Iran and encourages US investment. It has been working hard to promote westbound pipelines from Central Asia, particularly the Baku-Ceyhan oil pipeline, which will run from Baku, Azerbaijan, through Tbilisi, Georgia, to the Mediterranean port of Ceyhan, Turkey.

The hardline position toward Iran has been consistent for over a decade, and the terrorist attacks on the US and ensuing events have not altered it. The US military's success against Al-Qaeda and the Taliban in Afghanistan has helped stabilize the country and may pave the way for Caspian Sea pipelines.

The US has established closer relationships with Uzbekistan, Georgia, and other Central Asian countries, and that has also helped boost US oil company investment in the region.

Regional competition

Central Asia has problems of its own, ranging from overlapping claims to energy resources and territorial disputes to ethnic conflicts. Competition among its countries, particularly those surrounding the Caspian Sea, and with Iran and Russia has been fierce. Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and Turkmenistan have opened their oil and gas sectors to foreign investment, which has broadened the field.

All of these factors have a great impact on how and where pipelines will be built. Central Asia has four options for future pipeline routes, each with pros and cons:

- North-Northwest option. Geographically and logistically this is the easiest option. Russia has a complex but poorly maintained pipeline system; linking to it is the fastest way to transport oil and gas out of Central Asia. After independence, a few countries opted for this solution, but they have come to resent Russia's control of the export market and hard currency. For some, bypassing Russia provides enough of an impetus to develop alternative routes despite extra cost or risk.

- Westbound option. Initially, the proposed Baku-Ceyhan pipeline alone received US support. Although other options have since emerged, the Baku-Ceyhan and similar pipelines remain the most favored by the US. One drawback is the preliminary target market: Europe. Companies are wary about investing billions of dollars to supply a mature market with limited growth potential.

- Eastbound option. This option proposes that oil and gas be transported through long-distance pipelines to China and eventually the rest of Asia-Pacific. Currently under consideration are an 1,800-mile oil pipeline from Kazakhstan to China's Xinjiang region and a 4,200-mile gas pipeline from Turkmenistan to northern China. This eastbound option is the most direct way to link Central Asia and the Far East, but it is also the most expensive and geographically difficult option for pipeline construction at present. However, it remains an attractive long-term alternative.

- Southbound option. Two pipe- lines-one to Iran and another to Pakistan and India through Afghani- stan-are under consideration here. Although the Iran route is by far the more economical of the two, the US's Iran and Libya Sanctions Act and the Bush administration's labeling of Iran as an "axis of evil" have made it difficult to attract investors. India's desire to bypass Pakistan completely creates obstacles to building the second pipeline.

Forecast

Central Asia is eager to join the Middle East in fueling Asia-Pacific's growth, but a solid energy triangle among Asia-Pacific, the Middle East, and Central Asia will be difficult to form in the coming decades.

Central Asia's energy potential may be great, but it is not another Middle East. Its ability to satisfy Asia's growing energy demand is limited. Direct energy links to the Far East can be made only through long-distance pipelines, which are very costly. Central Asia's link to South Asia is complicated by instability and lack of infrastructure in Afghanistan and the decades-old conflict between Pakistan and India.

An indirect link and sealane connection through Iran and the Persian Gulf not only defeats the purpose of diversifying Asia-Pacific's oil supply, but it also garners strong objections from the US. As the bond between Asia-Pacific and the Middle East grows stronger, Central Asia's energy ties to the Far East will remain weak. Until southbound routes can be revived or technologies improved to justify long-distance pipe- lines through China, it will be a long time before Central Asian oil and gas exports can reach the fast growing Asia-Pacific market.

Central Asia's primary target for energy exports in the near future will be Europe, particularly East Europe, and Russia. In light of Central Asia's regional politics, its relationship with Russia, and the influence of the US and other Western countries, fierce competition among its countries over oil and gas routes will continue-as will Asia-Pacific's need to broaden its energy supply.

The scarcity of viable alternatives will further enhance the Middle East's role as Asia-Pacific's primary oil supplier. Strategies that address energy security and redefine the concept must be developed. Any strides made in diversifying energy and developing effective supply should spread to energy conservation, better use of natural gas and renewable energy, energy efficiency, and improvement of energy regulation systems throughout the region, particularly in developing countries.

References

- East-West Center energy database, April 2002, Honolulu.

- Energy Information Administration, "Short-Term Energy Outlook," Apr. 8, 2002, Washington, DC.

- EIA, International Energy Annual, May 2002, Washington, DC.

- Ibid.

- See also Robert Smith, 2001, "Politics, production levels to determine Caspian area energy export options,"(OGJ, May 28, 2001, p. 33).

- Ibid.

- EIA, "Caspian Sea Region," February 2002, Washington, DC.

Acknowledgment

The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the East-West Center.

This article was originally published by the authors as "Managing Asia-Pacific's Energy Dependence on the Middle East: Is There a Role for Central Asia?" in East-West Center's Asia-Pacific Issues, No. 60, June 2002.

The authors

Kang Wu is a fellow at the East-West Center in Honolulu (www.eastwestcenter.org). He conducts research on energy economic links, energy security, the environmental impact of transportation fuel use, and energy and economic policies in China and the Asia-Pacific region, with a particular emphasis on oil and gas.

Fereidun Fesharaki is a senior fellow at the East-West Center. He is the author or editor of 23 books and monographs and numerous technical papers on energy issues. His work focuses on downstream oil markets, OPEC policies, and Asia-Pacific oil and gas markets. He is a member of the Council on Foreign Relations and served as president of the International Association for Energy Economics in 1993.