US refiners, EPA continue maneuvering as low-sulfur fuel deadlines loom

In their efforts to meet new low-sulfur motor fuel requirements, US refiners face an uncertain regulatory future.

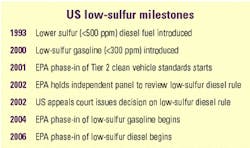

Tougher standards for gasoline come sooner than the new diesel rules but are seen as less problematic for industry to meet. The US Environmental Protection Agency under former President Bill Clinton issued the gasoline rule after years of negotiations with refiners, automakers, and environmental groups.

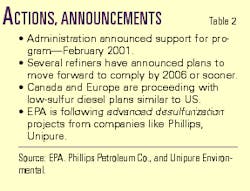

When President George W. Bush took office this year, his regulators clarified the gasoline rules slightly. Nevertheless, the tenets and timetables of both the gasoline and diesel standard remain largely intact.

Both the gasoline program, which starts in 2004, and the diesel program, which begins in mid-2006, seek to give industry flexibility.

Both regulations include:

- Establishing a market-based credit system designed to reward companies that reduce sulfur levels sooner than required.

- Allowing industries to use an averaging program to meet both car-emission and low-sulfur standards.

- Allowing auto manufacturers and refiners to meet strong interim standards while they work towards full compliance of the new standards.

- Providing small refiners with extra time to meet sulfur standards.

Clean air rationale

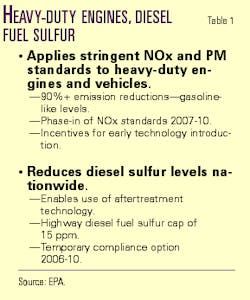

To comply with federal clean air legislation, EPA in the late 1990s moved forward with two new emission reduction programs: one for cleaner passenger vehicles and cleaner gasoline; the other for cleaner diesel fuel and cleaner heavy-duty trucks and buses (Table 1).

The first program, called "Tier 2," puts the burden on both automakers and oil companies by addressing tailpipe emissions and gasoline as a single system. Beginning in 2004, emission standards for light-duty trucks, minivans, and sport utility vehicles will be the same as for automobiles. Also in 2004, US refiners and gasoline importers must start paying stricter attention to fuels' sulfur levels.

EPA says refiners may make gasoline with a range of sulfur levels as long as all their own production is capped at 300 ppm and their annual corporate average sulfur levels are 120 ppm.

In 2005, sulfur levels must drop far more dramatically: The refinery average will be set at 30 ppm, with a corporate average of 90 ppm and a cap of 300 ppm. Both average standards can be met with use of credits generated by other refiners who reduce sulfur levels early, EPA said.

In 2006, refiners must meet a 30-ppm average sulfur level with a maximum cap of 80 ppm.

Western market delays

Gasoline produced for sale in parts of the western US (Alaska, Colorado, Idaho, Montana, New Mexico, North Dakota, Utah, and Wyoming) will be allowed to meet a 150-ppm refinery average and a 300-ppm cap through 2006 but must meet the 30-ppm average, 80-ppm cap by 2007.

EPA reasoned that those eight states (along with nearby tribal lands) should be allowed to have a longer lead time for two reasons:

- The kind of air pollution that low-sulfur fuels help correct was a less pressing problem in those areas.

- EPA was worried that there could be possible supply problems if the eight states were held to the same schedule as other areas because of "the relative difficulty of producing or obtaining, through product transport (via pipeline, truck, rail or barge) adequate supplies of gasoline that would meet the requirements of the national low- sulfur gasoline program."

Small refiners

Another area of flexibility built into the gasoline rule applies to small refiners, many of which produce fuels that will be marketed in the eight states that already have longer compliance lead times.

Small refiners (those with no more than 1,500 employees and a corporate crude oil capacity of no more than 155,000 b/d) can follow less stringent interim standards through 2007, when they must meet the final sulfur standards. Small refiners that demonstrate a severe economic hardship can apply for an additional extension of up to 2 years.

So far, two refiners have already met EPA's economic hardship test.

In May, the National Cooperative Refining Association in Kansas and Wyoming Refining in Wyoming requested and received more lead time to produce lower sulfur gasoline. The relief allows refiners additional time (21/2-4 years), depending on each refiner's specific financial hardship to meet the low-sulfur specifications.

"The relief I am granting will give these refiners the ability to continue providing gasoline to consumers while moving ahead to provide cleaner air for all Americans," said EPA Administrator Christine Todd Whitman at the time of the decision. "This approach is consistent with our goal to take actions that help businesses reduce harmful air pollution to create a strong, healthy environment."

EPA says that under the "Tier 2" program, automakers will make passenger vehicles 77-95% cleaner than those on the road today; refiners will reduce the sulfur content of gasoline by up to 90%.

And when the new tailpipe and sulfur standards are fully implemented, Americans will benefit from the clean-air equivalent of removing 164 million cars from the road each year, EPA says.

And as newer, cleaner cars enter the national fleet, new tailpipe standards will significantly reduce emissions of nitrogen oxides from vehicles by about 74% by 2030.

The standards also will reduce emissions by more than 2 million tons/year by 2020 and nearly 3 million tons/year by 2030.

Consumers can expect to pay about 2¢/gal more because of the rules but will see health and environmental benefits that will total $25.2 billion/year, according to EPA.

Diesel timetable

Together, refiners expect to spend at least $5 billion to meet EPA's low-sulfur gasoline program. It's money, however, that for the most part has already been factored into many company's long-term spending plans.

That's be cause industry is comfortable enough with the agency's rule that it is unlikely the regulation will be seriously challenged in court. And EPA has signaled it has no plans to delay the program (Table 2).

The same cannot be said about the agency's diesel program.

As the rule now stands, sulfur in about 80% of the highway diesel fuel used in heavy- duty trucks and buses would have to be reduced from today's maximum 500 ppm to 15 ppm by June 1, 2006. The remaining 20% of supply would need lower levels by 2010.

At the terminal level, highway diesel fuel sold as low-sulfur fuel will be required to meet the 15-ppm sulfur standard starting July 15, 2006. For retail stations and fleets, highway diesel fuel sold as low-sulfur fuel must meet the 15-ppm sulfur standard by Sept. 1, 2006.

As with gasoline, refiners may delay making their own low-sulfur diesel blend system-wide through averaging, banking, and trading component. This "temporary compliance option" starts June 2006 and lasts through 2009, with credit given for early compliance before June 2006.

Under this option, up to 20% of highway diesel fuel may continue to be produced at the existing 500-ppm sulfur maximum standard, although it must be segregated from 15-ppm fuel in the distribution system and may only be used in pre-2007 model year heavy-duty vehicles.

EPA also is providing additional hardship provisions for small refiners to minimize their economic burden in complying with the 15-ppm sulfur standard and to give additional flexibility to refiners that operate in those western states identified under the provisions of the Tier 2 gasoline-sulfur program.

The agency maintains that the credit programs and phase-in provisions will give refiners the option to stagger their gasoline and diesel investments. EPA also says any refiner, large or small, may seek further delays under a "general hardship provision" on a case-by-case basis, although under what conditions such a delay could be granted remains unclear.

Automakers meanwhile must make by model year 2007 heavy-duty trucks and buses with pollution cut 95%. EPA and automakers maintain that the sulfur in diesel fuel must be dramatically lowered to allow modern pollution-control technology to be effective on the new trucks and buses. On a dollar-basis, EPA says the new diesel program will translate to $70 billion/year in health benefits while only costing $4.3 billion/year to consumers.

Cost benefit tradeoffs

But are the diesel rules a truly cost-efficient way to reduce harmful air pollution?

Industry says the rule as it now stands could cause fuel shortages and is too expensive to justify. Refiners estimate that the rules could add 15-50¢/gal to retail diesel prices, compared with the pennies per gallon calculated for the gasoline rules.

Government estimates of the diesel rules costs are much lower: EPA says most refiners may be able to produce low-sulfur diesel for as little as 2.5¢/gal; at the volumes needed to meet demand, however, costs could be as high as 6.8¢/gal, according to the US Energy Information Administration. EPA estimates motorists will likely pay an average of 4¢/gal extra for diesel because of the rule.

"Reducing diesel fuel sulfur content to the level under consideration by EPA poses difficult technical and engineering challenges for the refining industry and imposes significant capital requirements and operating costs," says the National Petrochemical and Refiners Association.

"NPRA has stressed to EPA that it supports reasonable reductions in diesel sulfur levels, but that regulators must recognize that extremely low numbers could cause supply and capacity-related problems. NPRA has also told EPA that very low diesel-sulfur numbers, on top of the capital requirements for Tier 2 gasoline sulfur requirements and the imminent regulatory activity affecting air toxics and methyl tertiary butyl ether (MTBE) usage, cause great concern within the refining industry."

NPRA supports diesel on-road sulfur reduction to no lower than 50-ppm caps, no earlier than 2010, with no specified average.

Lawsuit filed

The trade association asked EPA, under the administrations first of President Bill Clinton and then of George W. Bush, to reconsider the rule, but the agency declined.

On Feb. 2, 2001, NPRA sued EPA in the US Court of Appeals for the DC Circuit for review of EPA's diesel-sulfur rule. NPRA said then that it believed EPA had exceeded its authority in issuing the diesel rule and that the rule, if left unchanged, threatened consumers with cost increases and significant shortages in supplies of America's premier commercial transportation fuel.

Soon after, a report by EIA made at the request of the House Committee on Science added some legitimacy to industry's argument in the eyes of White House policy makers. The agency said it could not predict whether refiners and importers will be able to supply enough low-sulfur diesel fuel to meet market demand in 5 years.

EIA noted that highway diesel represents about 12% of total petroleum consumption, compared with 43% for gasoline. Consumption of highway-grade diesel (500 ppm) was 68% of the distillate fuel market in 1999, while 9% went to nonroad (rail, farming, industry) and home-heating uses. Higher sulfur distillate (more than 500 ppm) is used solely for nonroad and home heating and comprises the remaining 32% of the market, EIA said.

EIA further noted that the number of vehicles in 2006 that will need low-sulfur diesel to run properly will be small because few new vehicles requiring the clean fuel will still be on the road. EPA could then have the option of temporarily reducing the required amount of the new fuel on the market, EIA said.

EIA's report didn't win over everyone, however.

Reacting to the report, clean air groups accused the agency of using "selective" data to undermine the rule.

"This report uses selective information in an obvious attempt to help the oil industry undermine EPA's new diesel fuel standards," said Frank O'Donnell, executive director of the Clean Air Trust (OGJ Online, May 8, 2001).

Despite environmental groups' criticisms, the EIA report produced the desired effect for industry: EPA began backpeddling.

About a month after EIA's study, EPA signaled it might second-guess the diesel rule (OGJ Online, June 6, 2001). However, it took 2 more months for the agency to outline its full intentions. In a Sept. 27, 2001, letter to Sen. James Jeffords (I-Vt.), chairman of the Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works, EPA Administrator Whitman offered detailed instructions on the timeline EPA envisions for the controversial diesel rule.

The first step she said would be a biennial assessment, conducted by EPA technical experts, of the progress auto makers and the oil industry are making toward implementing the program.

The agency would also convene an outside panel of experts to assess independently the progress of affected companies:

- Manufacturers of diesel engines and emission-control systems in developing technology to reduce engines' exhaust pollutants.

- The fuels industry in developing and demonstrating technologies to lower sulfur levels effectively. The experts will include refiners, automakers, environmental groups, and other interested stakeholders.

The independent review will start in May 2002 and work through the summer, Whitman told the committee. Lobbyists say that if EPA decides to delay the diesel program, a decision would be made soon after the review was complete-now scheduled for September 2002

More legal action

Despite Whitman's letter to the Senate committee, the legal battle between industry and EPA continues.

NPRA, joined by the American Petroleum Institute, Society of Independent Gasoline Marketers of America, National Association of Convenience Stores, and Antek Instruments, filed legal briefs with the US Court of Appeals for the DC Circuit. They claimed in the Oct. 1 action that EPA disregarded its duty to ensure an adequate supply of diesel fuel in the early years of the program. A decision is not expected until next spring (OGJ Online, Oct. 3, 2001).

Whether Congress decides to circumvent the courts and direct EPA to delay the diesel fuel rule remains uncertain. If world oil market conditions remain fairly stable, there will be much less pressure to interfere, especially if fuel prices are within moderate levels, lobbyists say. But a sudden supply shock caused by Middle East tensions could force lawmakers to consider the issue.

Automakers seek more

Even if EPA, on its own or through the courts, gives refiners a temporary reprieve from low-sulfur diesel standards, there still will be public pressure to make cleaner fuels in the name of good environmental policy.

That's because automakers are aggressively lobbying government policy makers-especially in Europe where diesel passenger engines are popular-to require low-sulfur fuels as a cost-effective emissions control strategy.

And in the case of the US, automakers say they have compromised enough already.

In testimony before the US Congress and industry groups, automakers say they want even lower sulfur levels than what has recently been finalized.

"We're hoping the oil industry will provide the clean fuels that will help: 5-ppm sulfur or less for both gasoline and diesel fuel," Alliance of Automobile Manufacturers President and CEO Jo Cooper told the World Fuels Conference last September. "For gasoline, a distillation index cap at 1,200 or lower. For diesel fuel, we need much higher cetane, because it is as much an enabler of light duty diesels as low sulfur; much lower polynuclear aromatics for lower emissions; and better lubricity."

And if refiners aren't willing to improve fuel quality, automakers may be forced to be more aggressive about developing nonpetroleum sources, she said.

"Our members have worked hard to develop the options for improving fuel economy. But the choices are quickly narrowing. They can continue to use petroleum-based fuels, albeit more efficiently, or they can turn more toward nonpetroleum fuels. Which way they turn will depend in large part on how clean any of these fuel choices become," Cooper said.

State pressure

Automakers are not the only stakeholders that refiners should be aware of in their ongoing fight to retool clean-fuel rules.

State support for low-sulfur diesel rules is strong because of the perceived clean air benefits of the fuel, despite industry warnings that supply may be compromised in some markets.

A state legislators' group this summer called on EPA not to weaken or delay standards that would dramatically lower the sulfur standard in diesel fuel.

"NCSL strongly supports EPA's engine and fuel standards and opposes efforts to either delay or weaken the fuel sulfur standard or delay or weaken achievement of the engine emission standards," said a resolution approved by the National Conference of State Legislators. NCSL delegate James Hubbard (D-Md.) introduced the resolution (OGJ, Sept. 10, 2001, p. 38).

Environmental groups also continue to lobby to preserve the low sulfur standards.

Nonroad diesel

Another uncertainty for refiners is which steps, if any, the agency will take to lower sulfur levels in nonroad diesel.

EPA officials this fall said they currently are conducting a technical review of future nitrogen oxide, hydrocarbon, and particulate-matter standards and test procedures. It is not known when the agency might seek to issue a new rule.

So, for now at least, that battle has not been waged, although heavy-duty engine manufacturers and refiners are watching the agency closely.

EPA Administrator Christine Todd Whitman has said two refiners have met EPA's economic hardship test; this relief will "give these refiners the ability to continue providing gasoline to consumers while moving ahead to provide cleaner air for all Americans ellipse [and is] consistent with our goal to take actions that help businesses reduce harmful air pollution to create a strong, healthy environment."