The Russian Oil & Gas Industry: Analysis raises questions about Russian tax proposal

The Russian legislature should consider changes to recently proposed tax changes designed to encourage oil and gas investment. As drafted, the new tax scheme would not produce intended results.

The State Duma of the Russian Federation on June 7, 2001, approved in the first reading a package of laws related to taxation of mineral industries, including draft Chapters 26 and 27 of the Tax Code prepared by the government.

Draft Chapter 26 provides that mechanisms and quantitative parameters for import and export tariffs be established by law rather than governmental decree. If it becomes law, this part of the new regime would encourage investment by providing more stability than existed before for oil companies. It would decrease export-related risks of project financing in the oil industry.

M. Khodorkovsky, chairman of OAO Yukos, said during a meeting of Russian President V. Putin with key Russian businessmen at the end of May that export tariffs represented 30% of oil company tax payments during 2000. The figure for the first quarter of 2001 rose to 49%.

Draft Chapter 27 is more troublesome. It would change taxation of oil and gas production by introducing a tax on production of raw materials. The new tax is to replace three existing taxes:

- Royalty (6-16% of gross revenue).

- Mineral resource tax (10% of gross revenue less the value of the taxpayer' spending on exploration).

- Excise tax (66 rubles/tonne of oil, equal to 2.5%, according to calculations of the Ministry of Finance based on the weighted average price of Russian oil and taking into consideration export and domestic sales).

If it becomes law, the new tax will be based on current methods of royalty calculation, with the rate unified for all projects over the country and equal to 16.5% of gross revenue, at market value, from oil and gas produced. But during 2002-04, and only for oil, it will be valued on a flat-rate basis equal to 425 rubles/tonne of the "floor take" deflated by fluctuations of a global marker, dated Brent crude.

The main reason for this special tax collection, according to the government, is to move the oil industry's point of tax impact toward the wellhead. The aim is to extract maximum economic rent in the natural-resource producing industries. The government wants the tax to counter transfer pricing, which vertically integrated companies have used to reduce their exposures to Russia's excessive taxes.

But does this proposed new tax system for oil and gas production correspond to the principles of fair and effective organization of the tax system in the industries related to mineral rent collection? Will it sufficiently stimulate investment in exploration and production to compensate for depletion of Russia's existing fields?

Major Russian oil provinces, including West Siberia, have entered late stages of development. Russia as a whole is approaching this stage as well.

Development of new provinces, such as Timan-Pechora and East Siberia, can only slow down this tendency. Potential reserves volumes and economics of development in the new provinces are less favorable than in West Siberia.

A study entitled "Russian Energy Strategy to the Year 2020" projects that, under assumptions of high domestic economy growth, demand for oil might exceed potential supply from existing licensed and unlicensed fields in 2015. The need for investment in exploration and production-and a tax regime that encourages it-is obvious.

Royalty, production tax

Royalty, the mineral resource tax, and the tax on production that would replace them under the new tax regime are economically similar.

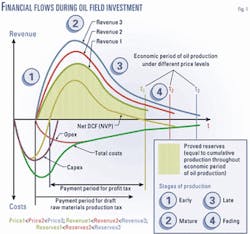

All of them are based on gross revenue and thus have been mostly depressing investments in oil and gas. The effect is pronounced in early stages of a production project, when net present value (NPV) is negative (Fig. 1). The flat-rate excise tax has the same depressive influence on investment.

The proposed tax system would seem to decrease the maximum rate from the current cumulative rate of 28.5% (16% + 10% + 2.5%) to 16.5%.

But that's in theory. The Ministry of Finance wants the proposed tax on production to generate revenue equivalent to that yielded by the royalty, mineral tax, and excise that it replaces.

According to the ministries of Natural Resources and Finance, the all-Russia average royalty take slightly exceeds 8%, half its maximum value according to the law entitled On the Subsoil.

The law excludes from the mineral tax subsoil users that:

- Conduct exploration presented in their licensing agreements at their own cost or through any other kind of nonstate financing.

- Have compensated the state for all previous exploration expenses it incurred to prove the reserves under development.

- Are investors in projects covered by production sharing agreements (PSA).

Thus the all-Russia effective rate of mineral tax is about 6%.

The proposal's effect on maximum tax rates is therefore much less than the 12 percentage point cut it seems to be (28.5% less 16.5%).

And taxpayers now excluded from the mineral tax, especially investors in greenfield projects and PSAs, face a nearly two-fold increase. They now pay tax at the estimated average rate of 10.5% on revenue-the average royalty of 8% plus the 2.5% rate implicit in the excise tax.

A US oil company working in Russia told the State Duma that its royalty, mineral tax, and excise tax payments amount to 170 rubles/tonne of oil-40% of the flat rate proposed for oil during the new tax regime's initial years.

In view of the diminishing size and profitability of new discoveries in Russia, a reduction in the all-Russia average royalty rate of 8% deserves attention. In recent months, expansion of the royalty rate range from 6-16% to 0-16% has been broadly discussed in the government and Duma. The idea gave way to the proposal for a 16.5% universal rate of tax on production.

Negotiable royalty

Under current law, a fixed royalty rate for a single project can be established within a 10-percentage-point range. The negotiating character of this procedure is not clearly drafted in the legislation. In practice, an investor must show in the feasibility study the royalty rate needed to reach an appropriate internal rate of return (IRR) of the project.

The possibility of varying the royalty rate for an individual project is, in the view of this author, stimulative to investment. It acts as an opportunity to seek a balance of interests between the state and an investor and accounts for special characteristics of individual projects. By proving an appropriate royalty rate in the given range, an investor can try to compensate for unfavorable geological, geographical, and other conditions.

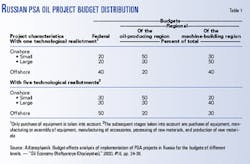

For the state, the indirect effects of this economic stimulation are great. They result from expenditures by companies directly involved in oil projects in companies not directly involved. In most cases, regional budgets of oil-producing regions experience a more significant indirect spending effect than do machine-building regions (Table 1). And the multiplier effect, which occurs as commerce generated by an oil project ripples through the economy, can be great.

Implementation of a fixed (nonnegotiable) royalty in the form of a tax on production-twice as high as the currently effective royalty rate-will narrow the oil industry's aggregate taxable base by increasing the floor economic limits (volume of proved reserves) of individual fields examined for development. Thus the state will not receive the incremental direct, indirect, and multiplier effects from fields that the proposed tax scheme discourages from development.

Those who will suffer most from a new tax among the investors are nonintegrated Russian companies developing small and medium-sized fields (almost 80% of all the fields in the State Register are small fields). Vertically integrated oil companies (VIOCs) have been profiting from scale economies, while nonintegrated companies have been extracting their shares of economic rent through specialization.

AssoNeft, an association of small and mid-sized oil companies, notes that the reserves structure for VIOCs is more favorable than for nonintegrated companies. Small and medium-sized fields, with reserves less than 30 million tonnes, make up 59% of the holdings of nonintegrated companies, compared with 28% for VIOCs. Large fields, with reserves of 30-300 million tonnes, claim equal shares of the holdings of the two groups: 41%. And nonintegrated companies hold no ultralarge fields, with reserves exceeding 300 million tonnes, which account for nearly one third of VIOC holdings (Fig. 2).

AssoNeft says that more than half the reserves volume held by nonintegrated companies is marginal.

So it will be nonintegrated companies, producing in total about 10% of Russian oil, that would suffer first and most from the proposed production tax's effective raising of the economic threshold for development of new fields.

In general, highly profitable projects, mainly ultralarge fields, would be undertaxed by the flat-rate levy on production. Marginal projects, usually medium and small fields, would be overtaxed, and many, as a result, would not be developed. This is the category claiming a growing share of activity in Russia.

The unified tax on production also would decrease competitiveness of medium-sized and small nonintegrated companies. That will stimulate mergers of nonintegrated companies by major VIOCs and thus might reduce competition in the Russian oil industry. The effect would relax pressure on VIOCs to improve efficiency and reduce costs. They would then become less competitive internationally.

So implementation of the tax on production in its current wording would increase the tax burden for selected categories of investors, basically for nonintegrated companies and future investors, discouraging or even preventing investments except by the VIOCs. Investments in new projects would be less attractive for VIOCs as well in comparison with their investments in currently producing fields. Overall, the proposed tax would have a chilling effect on investment.

There are indications that the government has considered a further increase in tax on production for all categories of taxpayers. According to Kommersant, a weekly Russian business magazine, Vice-Prime Minister A. Koudrin said in mid-June, "Taking into consideration [the] decrease in profit tax rate, [the] rate of the tax on production can be increased for oil."

In this author's view, the observation reflects the still-dominant fiscal orientation of decision-makers in the Russian government.

Production, profit taxes

The fixed royalty rate will also narrow the taxable base for profit tax in individual projects. Under the revenue-based tax on production with a fixed and high rate, to be paid from the very start of production, the investor will have less current revenue to reinvest during the capital-intensive development phase of a project. That will increase the need for debt financing for the project. And it will increase project costs and decrease the net revenue for profit tax collection.

On June 22, the Duma approved in the second reading draft Chapter 25 of the Tax Code, entitled "Profit Tax." The draft cuts the profit tax rate to 24% from 35%. The government initially proposed a rate of 25%, and deputies proposed a rate of 23%. The draft chapter's rate is a compromise of those positions.

The government has presented the rate cut as a step supportive of investment and a decrease in tax pressure. According to A. Makarov, head of the Duma's Committee on Budget Expert Council, the all-Russia effective rate of the profit tax is not 35%, but only 19.5%, after the effect of concessions. These include the important "investment-related" allowance, which reduces the profit tax base by as much as 50% to be equal to the sum of capital expenditures reinvested in a project. Concessions apparently would cease under the draft proposal.

If the proposed regime became law, therefore, taxpayers, according to Makarov, would face not a decrease but an increase of tax burden in practice. Some government officials agree with these figures. Other officials say that the effective rate of the profit tax is 26-27%. But independent experts' calculations put the current rate at only 15.7%. So it is more probable that a decrease in the nominal rate will mean a large increase in the effective rate.

Furthermore, it is even more harmful for oil companies to lose their investment-related allowance against the profit tax. Cancellation of the allowance means that project costs will increase by the value of their price of borrowings. This is because companies will face less investment resources when refinancing capital expenditures from after-tax profit compared with the case when such expenditures are refinanced from pretax profit.

Also, many companies that have been using this allowance have not finished their capital expenditures spending. Uncompensated deletion of this allowance would jeopardize existing investment programs.

The state, therefore, would have to extend application of the allowance project by project with grandfather clauses to ensure their completion. To put these clauses into legal force, the state would need to put each one of them into corresponding licensing agreements. The adjustments would require much time, during which the affected companies would be under obligation to continue capital spending programs in their licensing agreements from after-tax rather than pretax profit.

On the other hand, rearrangement of licenses is too risky for the companies, even if the intention is to grandfather the investment-related allowance. The state might use this procedure for its own purposes, as well, such as to check on or control projects. That would definitely slow development of projects in the middle of their capital expenditure programs and worsen their discounted cash flows.

This decrease of the profit tax rate will have no real stimulative effect on foreign investors. Under double-taxation treaties between Russia and countries of foreign companies working in Russia the decrease of tax payments in the host country would be offset by increases of tax obligations in their home countries. So this change in legislation might stimulate only Russian companies in domestic operations and be treated worldwide as an attempt of the Russian state to protect domestic companies from foreign competitors by means at odds with World Trade Organization principles.

License stability

Another problem to be solved if the new tax approved by the State Duma becomes law is stability of existing licensing agreements.

The proposed tax would substitute for royalty specified in licensing agreements particular to individual projects. Each such agreement has a maximum duration of 20 years (if a production license is issued) or 25 years (if a combined exploration and production license is issued). The earliest were issued in 1992 after the law On the Subsoil came into force.

No oil company would like to revisit a license before its expiration date. Companies would treat any attempt by the state to do this as a violation of basic business rights. That is a purely legal aspect of the problem. In theory, it might be solved if "grandfathering" is implemented for more than 10,000 existing licenses. But in this case two taxation systems under one licensing regime would appear in Russia: one with royalty and without a tax on production, the other with a tax on production and without royalty.

The economic aspect of the problem is no less difficult. Direct substitution of royalty specified in the licensing agreement by the tax on production would push some currently operated projects out of business by reducing project NPVs and lives.

Production curves

The new tax would create a simple and thus transparent system of rent collection related to world oil prices. That is favorable to investment.

While it accounts uniformly for one major externality-the price of crude oil-it does not differentiate among various project internalities, such as stages of investment at the time the law takes effect or production and NPV curves (Fig. 1).

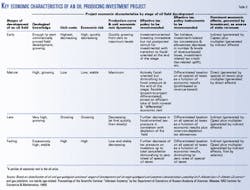

From this author's point of view, the balanced system of project-based taxation of oil production must take into consideration objective trends definable in relation to financial flows of an oil project from its early to fading stages of production (Table 2).

These trends can be summarized as follows:

- The portion of economic rent in the price of oil fluctuates in relation to the oil production curve. That demands changes in the aggregate tax burden on the investor of the project through the project life-cycle.

- The economic risk of oil field development decreases at first then starts to grow following the trend of unit cost changes of the project.

- An investor receives from the project only one group of effects (profit, the direct effect), while the state receives three groups: direct, indirect, and multiplier effects. At the different stages of an oil field development the role of each individual effect in the aggregate for the state differs greatly. The direct tax effect will be major only at the mature stage of the field development. At other stages of production (early, late, and fading) state receipts will be predominantly through indirect and multiplier effects.

- The tax burden might be fiscally oriented only at the mature stage of the project. At other stages of the project fiscal pressure on an investor needs to be weakened up to full deletion from the special taxation at the fading stage. That will enable the state to receive maximum value of the combined three effects through project life.

- Throughout all production stages, taxation needs to consider different conditions of the individual project and thus to optimize its collection of economic rent.

In the author's opinion, the law drafted by the government and approved by the State Duma in the first reading as Chapter 27 of the Tax Code does not take into consideration those objective trends in the financial flows of oil-production projects. It thus does not create a tax system that balances fiscal and investment intentions of the state. Moreover, major tax principles presented by the government in this chapter contradict principles presented by the government in its latest long-term energy-related development programs. Those principles are set out in two documents: "Key Provisions of Conceptual Framework for Russian Oil & Gas Development" and "Russian Energy Strategy to the Year 2020" (Table 3).

Both documents declared the need to create a differentiated-throughout the project life-cycle-oil and gas taxation scheme, on the one hand, and a system of investment stimulus at the different stages of production, on the other hand. The latter might include:

- At the early stage, where the dominant effects for the state are indirect effects from capital expenditures plus multiplier effects generated by indirect ones-tax holidays, tax allowances on the value of reinvestments in the project (currently exists for the profit tax but to be deleted by the new draft Chapter 25 on the profit tax of the Tax Code), reduction of revenue-based taxes, and investment-related tax credits, such as tax-related uplift.

- At the mature stage, where the dominant effects for the state are direct effects (oil-related taxes) plus multiplier effects generated by direct ones-differentiation of all "special" taxes based on "internal" characteristics of the project.

- At the late stage, where the dominant benefits for the state are indirect effects from operating expenditures plus multiplier effects from indirect ones-differentiation of all "special" taxes, and decreases in their values through depletion allowances.

- At the fading stage, where the dominant effects for the state are indirect effects from operating expenditures plus multiplier effects from indirect ones (mainly from workers' salaries)-differentiation of all "special" taxes and further decreases of their values to the zero level.

Further incorporation into legislation of this proinvestment mechanism is a major task for the State Duma deputies for the second reading of the draft law on Chapter 27 of the Tax Code.

Both chambers of Russia's Parliament approved in mind-July this new mechanism of taxation of mineral industries without any major changes compared with its structure discussed earlier, thus leaving room for further pro-investment improvements of the oil and gas-related taxation either to the next generation of deputies or to the next government.

The author

Andrei A. Konoplyanik is the president of the Energy and Investment Policy & Project Financing Development Foundation, an independent, nongovernment think-tank (www.enippf.ru). He is a former deputy minister for fuel and energy of Russia, with responsibility for external relations and direct foreign investments. He is currently an adviser to the Ministry of Energy and Ministry of Economic Development and Trade. His e-mail address is [email protected]. Konoplyanik has a PhD in energy economics from the Moscow Institute of Management. He has published numerous articles, monographs, and books on Russian and international energy economics and Russia's oil and gas operations.