Future of deepwater, Middle East hydrocarbon supplies

Since the 1970s the International Energy Agency, through its World Energy Outlook publication, has provided the most reliable energy projections of the world's energy future. IEA analyzes oil and gas supply projections based on its own projected combined commodity price, together with estimates of spending on finding and developing resources and the world's hydrocarbon resources (proven, possible, and probable).

The most recent publication outlines two major conclusions: First, oil supply is expected to grow to 115 million b/d in 2020 from 76 million b/d in 2000. Second, gas supply is expected to grow to 3.5 billion tonnes of oil equivalent (toe)/year from 2.2 billion toe/year during the same period. Both are needed to meet projected demand growth in Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development countries and in developing countries.

The above supply projections are based on a series of assumptions: First, estimated incremental world oil and gas resources from reserve growth will be almost as great as resources from undiscovered fields. Second, oil supply from exporters outside the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries will mature in the next decade; Russia, West Africa, and Latin America will contribute most to non-OPEC supply gains. Deepwater fields located off Brazil, the rest of the former Soviet Union, in the Gulf of Mexico (GOM), and off Africa are expected to play a role by providing 7-9% of total world oil supplies by 2010. Third, additional gas supplies will increasingly come from remotely located onshore and offshore fields. Fourth, oil production in OPEC countries, particularly Persian Gulf member countries, will increase twofold over the period, subject to significant foreign investment. In this model, Middle East producers are assumed to be swing producers with the capacity to increase production further.

Most industry observers would like to trust the above assumptions for the sake of our world economy and society. But can global deepwater production live up to expectations? Or can Middle East supplies increase as much as will be needed? The purpose of this article is to review these two aspects-first by analyzing deepwater exploration and production within an integrated framework and focusing on key case studies covering Egypt, Nigeria, and the GOM. Second, it will provide an overview of the current issues facing Middle East oil producing countries and the impact of politics on future Middle East oil supplies.

Deepwater exploration

The beginnings of deepwater exploration go back to the early 1960s. Initially, the required technologies differed little from that used on the shelf, and the rewards were clearly there. In the Outer Continental Shelf zone, i.e., 200-500 m of water, discoveries had totalled more than 30 billion boe.

But in the mid-1970s, the industry was ready for the next step. Partly as an extension of existing deepwater capability, partly driven by the spur of a perceived dwindling resource and the rush provided by the rise in oil prices, exploration moved into the new frontier of deepwater-beyond 500 m. Initially, the results were disappointing, with the exception of a handful of gas finds off Australia.

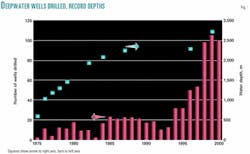

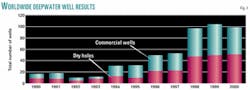

In the mid-1980s, the position changed, with large oil discoveries off Brazil and in the GOM, establishing these two areas as major deepwater hydrocarbon provinces. As expected, such results attracted global interest, leading to breakthroughs, namely the deployment of global deepwater E&P strategies and the introduction of fiscal regimes tailored to deepwater exploration (Fig. 1).

In the 1990s, exploration companies focused on over 60 deepwater basins worldwide. This global strategy has yielded good results, mainly in terms of the number of fields and volumes discovered. Nearly 120 fields were discovered, and these contributed 20% of the total oil and 7% of the gas discovered on a proven basis worldwide.

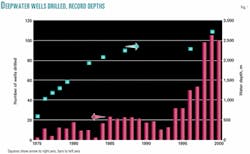

Of the discovered resource, at the end of 2000 the GOM dominated with over 10 billion boe, almost 90% of which is oil. Brazil is in second place with almost 9 billion boe, three-quarters of which was oil. West Africa-mainly Angola and Nigeria-was just behind Brazil, with about 8 billion boe.

Distinct from these three big provinces, which are all oil-dominated, the smaller provinces off Southeast Asia, the Nile Delta, and Northwest Europe appear to be gas-dominated (Fig. 2).

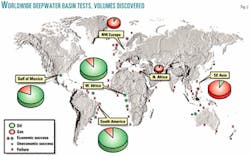

Unquestionably, all of the previous discoveries have been achieved at a very high cost. According to a US Energy Information Administration report that records aggregate exploration and development spending for more than 250 companies annually, oil and gas companies have spent a significant amount of capital just in the last decade (Table 1).

The supermajors and majors, companies with by far the largest deepwater exposure, rightly claimed that in the 1990s finding and development costs, a key parameter for determining the economic viability of oil and gas projects, rose partly as a result of global deepwater strategies. Today we know with certainty that F&D costs are higher in deepwater regions than in other regions (Fig. 3).

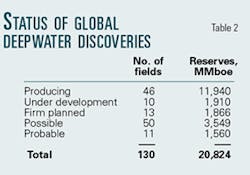

Regardless of how much success companies have had in deepwater, currently deepwater fields still account for only 2% of global oil and gas production. Furthermore, 60% of the total number of discovered deepwater fields and 32% of the total reserves-7 billion boe-remain in the "firm planned," "possible" and "probable" development categories (Table 2). Of these, 80% are located in 700 m of water.

It is important that, out of a large number of worldwide deepwater basin discoveries, only in Brazil did most of the reserves transform into real commercial developments, distantly followed by GOM and West Africa, even though E&P started in all three regions concurrently.

Analysts conservatively predict that deepwater production could represent 7-9% of the total global oil and gas production in 2010, after which a certain decline is expected. Other analysts are more optimistic and propose a thesis of a long period of continuous growth.

For us, it is interesting to see globally so many fields left unattended for long periods, while mature, low-potential areas such as US onshore and OECD Europe continue to attract large investments. If all the undeveloped reserves were put on stream at the same time for 20 years, their production would total 1 million b/d.

To better understand some of the current issues in deepwater E&P, we analyzed three important deepwater provinces: Offshore Niger Delta, Nile Delta, and the GOM.

Nigeria

Can the deep water off the Niger Delta produce the equivalent of production from 10 Bonga fields in the next decade?

For the last 50 years, Nigeria's crude oil exports have been produced primarily from shallow-water fields in the highly prolific Niger Delta area. Deepwater exploration began in 1993, and so far, 38 exploratory wells have been drilled, resulting in the discovery of four deepwater fields: Ukot, Bonga, Agbami, and Nnwa.

Inspired by the 1990s deepwater successes and recognizing that the Offshore Niger Delta is the hub for oil and gas activity in Nigeria, the troubled Nigerian government was able in 2000 to make significant improvements to the hydrocarbon fiscal regime. The government hopes that its strategy will help Nigeria increase its production to 3 million b/d in 2003 from 2.1 million b/d in 2000 and reserves, to 30 billion boe from 22 billion boe.

Finally, the government hopes that its plan would raise oil production to 4 million b/d and reserves to 40 billion boe by 2010. The government anticipates that the investment required to meet the first target is about $40 billion-$25 billion from private companies.

As currently planned, Bonga field will be the first deepwater oil and gas field in Nigeria to be developed-at a cost of $2.7 billion. The field, which is at least twice as large as the other discoveries in Nigeria, will have capacity to produce as much as 220,000 boe/d.

By the time production begins, the cycle time will have been almost 9 years.

The Niger Delta region has been extensively explored and often is considered to have the highest potential for monetizing deepwater reserves in West Africa. This expectation is supported by the fact that the Niger Delta has high quality hydrocarbon play systems, fiscal terms allow for relatively acceptable returns, and F&D costs are relatively lower than in other deepwater pro vinces.

However, even with these important comparative advantages, it is hard to imagine the Niger Delta deepwater region producing an additional 2 million boe/d-the equivalent of 10 Bonga fields producing-before 2010.

At present, reserve and production targets for 2003 seem unreachable. The required investment has not been matched, even considering Royal Dutch/Shell Group's recently approved $7.5 billion investment, which is a sum that only a few companies can afford.

Egypt

Egypt has four hydrocarbon provinces in which exploration is currently active: Upper Egypt, the Gulf of Suez-Eastern Desert-Sinai areas, Nile Delta-Mediterranean-north Sinai area, and the Western Desert.

During 1990-2000, the country's proven oil reserves decreased more than 30%, while gas reserves increased well over 100%. A small portion of the oil and 99% of all gas discoveries came from exploration in the Offshore Nile Delta.

More than 100,000 sq km of acreage is currently being explored off the Nile Delta. The well tests in this large province have so far been concentrated on the shelf, with very few wells drilled in deep water-127 wildcats, of which 17 have been drilled in water deeper than 100 m.

Known hydrocarbon play types include turbidite fans and channels in combination with structural and stratigraphic traps, submarine canyon valley fills, and salt-controlled traps in water depths of more than 1,800 m.

Other important play types are inverted half grabens that characterize recent deepwater gas discoveries such as Goliath, Scarab, and Saffron.

As in every hydrocarbon province, the future potential of deepwater Nile Delta province depends on geological factors. There are several critical limiting factors controlling hydrocarbon prospec tivity in this region, all of which are well understood: First, restricted identified source kitchen limited to burial depths impacts source presence and quality in parts of the basin.

Second, nonsystematic migration paths and provision charge to complex structures from deeper sources. This implies that hydrocarbon distribution probably is the result of original heterogeneity of the source, which significantly limits hydrocarbon accumulation potential in the basin.

Third, the preservation of hydrocarbons is limited to areas that have not been buried too deep and where major faults resulting from pervasive salt tectonism-typical in deepwater areas off the Nile Delta-have not modified the sea bed, indicating that these are not in connection with older intervals and possibly charge reservoirs.

Most geoscientists will agree that the coexistence of the previously mentioned critical factors are detrimental to this province. In addition, high F&D costs and the possible location of prospects in ultradeep water remain the main challenges for monetizing reserves in Nile Delta deepwater area.

The existing challenges undermine the potential of the basin and the strategic value of the recent successes to be developed in the future. Above all, these can prevent the Nile Delta deepwater area from becoming a significant world-class gas or oil supply region. Shell still hopes to strike commercial oil on its deepwater concession.

GOM

Despite the GOM having the largest number of discovered fields of all known deepwater basins, it also has the highest number of undeveloped fields, largely because the majority of the fields are not economic under most scenarios (Table 3). This is partly because the size of many of these fields is difficult to predict.

Mad Dog, one of the large deepwater discoveries in the GOM, has recently been in the news not only because it has been sanctioned but because the actual reserves could be half of what they originally were estimated.

The field was discovered in 1999 in 2,000 m of water and had estimated, predrill reserves of about 800 million boe. After completing a fast-track appraisal program, which consisted of four wells and accompanying sidetracks, the estimated reserves were revised downward to 400 million boe.

This situation is similar to that of Neptune, a large undeveloped deepwater discovery. Neptune caused considerable excitement upon its discovery and was a leading priority for the project sponsors a couple of years ago. But with reserves levels there lower than originally thought, Neptune development has fallen to the back of the lineup of undeveloped fields.

However, Mad Dog operator BP PLC and other sponsors say Mad Dog's fast-track development is on schedule for first oil at the end of 2004 at a cost of $1 billion. Without doubt, Mad Dog, Neptune, and other deepwater discoveries in the GOM that have seen their reserves revised downward will produce less oil than originally thought.

Keep in mind that Mad Dog represents a trend-opening discovery for the deepwater fold belt subsalt play, which extends elsewhere in the deepwater GOM. We just hope that Neptune and Mad Dog are the exceptions in the GOM.

Expenditure trends

In relative terms, during the 1990s, global E&D expenditure increased in most regions, but in Africa, FSU, the Middle East, and Latin America, E&D spending has remained significantly below that of mature US and OECD Europe. Why is that so if the reserve and economic rewards are potentially so large in deepwater basins?

A possible answer might be found in a simple but authoritative principle. If an asset such as a discovered field does not produce or have the capacity to produce, it becomes a fixed asset and therefore becomes less desirable as an investment. Assuming that all companies want to increase year-on-year shareholder value, they will not want to move ahead with projects that are relatively uneconomic.

After geological factors, relative F&D costs determine to a large extent which projects go forward. Deepwater pro vinces are therefore generally less attractive than other regions. High F&D costs also occur when deepwater exploration is accompanied by numerous dry holes, uneconomic discoveries, and few successes (Fig. 4).

Another possible explanation for relatively low E&D expenditure in regions such as Africa, in which E&P is predominately focused on deep water, may be that a large amount of the discovered undeveloped reserves is highly speculative and as such don't consistently form a key part of E&D budgets.

Perhaps, the answer is a combination of all three, but the outcome has significant implications in expected future deepwater oil and gas supplies.

Middle East reserves

Although world proved reserves are reported to be about 1 trillion bbl-of which two thirds are in the Middle East- this estimate may be artificially high.

Beginning in 1985, OPEC members, driven by the desire to increase their production quotas, which are related to the size of proven reserves, started reporting huge increases in their reserves. For example, in 1985, Kuwait reported an increase of 41%; in 1986, Venezuela doubled its reserves; in 1988, UAE reported a tripling of its reserves; and, in 1990, Iran and Iraq each doubled their proven reserves, while Saudi Arabia reported a 50% increase, by about 85 billion boe.

However, during the late 1980s, there were not enough wells drilled in any of these countries, or large new discoveries made to increase proved reserves by the amounts reported. Thus, most of the increases had to have been in inferred reserves-identified economic resources expected to be added to proved reserves as new wells are drilled and additional oil is expected to be recovered by improved production practices.

Because it is clear that the Middle East contains huge amounts of oil, all this time the reported reserve increases have been generally accepted, even though they may not meet the normal definition of proved reserves.

In 1990, it was explained that Saudi Arabian reserves might have been previously underreported, particularly when compared with the already increased reserves of other Persian Gulf states. In an effort to justify this increase, Saudi Aramco expanded the cut-off points for recoverable oil in the huge known fields, assuming higher percentages of the oil in place theoretically could be recovered. However, to achieve the higher theoretical recovery rates-50-60%-huge capital investments in water injection wells, pumps, pipelines, and water separation plants would be required.

Eventually, the produced fluid would approach 90% salt water, which would have to be separated and dispose of. There have been creditable reports that, in the 1990s, the Saudi government mandated that the oil reserves would not decline. Thus, in spite of the production of some 16 billion bbl of oil, Saudi reserves are 3.6 billion bbl higher now than in 1989.

Under the generally accepted definition, the current proved reserves of Saudi Arabia probably would be about 160 billion bbl, leaving some 100 billion bbl as inferred reserves that, at very considerable expense, could be converted to proved reserves. Similarly, Kuwait currently has about 86 billion bbl of proved reserves, with field growth potential of perhaps 10 billion bbl produced at significant additional expense.

In the UAE, 61 billion bbl of oil may be proved, leaving 37 billion bbl of inferred reserves potentially available at substantially higher cost. In Iran, perhaps 69 billion bbl of the 99 billion bbl reported as oil reserves qualify as proved reserves, while in Iraq it is possible that as much as 91 billion bbl of the reported 112 billion bbl of oil reserves may qualify.

Iraq hiked its proven oil reserves by 12% in 1996 even though no significant exploration work was going on at the time. In general, the Middle East region has reported nearly a doubling of proven oil reserves since 1980, to 695 billion bbl from 363 billion bbl, largely from inferred reserve additions.

Production, potential

IEA projects that Middle East OPEC oil production will have to rise to 47 million b/d in 2020 from almost 23 million b/d today (Table 4). Based on the current quotas and spare capacity, Saudi Arabia's share of the increase may be about 25% (5 million b/d), Kuwait, 15% (3 million b/d); Iraq, 20% (4 mil lion b/d); Iran, 10% (2 million b/d), and UAE, 10% (2 million b/d).

There is no doubt that Saudi Arabia and other OPEC Middle East countries can increase production, but how much and at what cost? Saudi Arabia carried out major development activity during 1991-95. It raised the production of 14 fields during this period and raised its sustainable production capacity to 10.8 million b/d, from 8.7 million b/d, with most of the increase occurring in Ghawar field.

Most of the effort involved the restoration of idle onshore and offshore production equipment and the installation of several gas-oil separation plants and gas compression plants in developed fields. The $36 billion expansion also included the enlargement of a seawater treatment plant and injection facilities at Ghawar and the drilling of production wells into lower reservoir zones in Safaniya. No other official plans have been revealed to expand beyond the current capacity.

In Kuwait, the reconstruction of oil production facilities damaged in the Gulf War had restored oil production capacity to about 2 million b/d by 1995. The oil lost to well fires is estimated at 3% of the proved reserves, yet OPEC data shows no drop in Kuwait's proved reserves of 96 billion bbl. Prior to the Persian Gulf war, Kuwaiti oil production capacity was about 2.5 million b/d; that figure remains the same today.

Although it has undertaken production cutbacks this year in collaboration with other OPEC nations, Kuwait still aspires to increase its sustainable production capacity to 3 million b/d by 2005 and 3.5 million b/d by 2010. The country's $7 billion production enhancement program, Project Kuwait, is a 25-year plan to increase Kuwait's oil production and to help offset production declines at the mature Burgan field with the help of foreign oil companies' investment and technology.

In particular, Kuwait aims to increase output at five northern oil fields: Abdali, Bahra, Ratqa, Raudhatain, and Sabriya. Unfortunately, the project has yet to be launched, in large part due to opposition from the Kuwaiti Parliament and demands for more information on the structure of the contracts.

In the case of Iran, many companies believe that oil production capacity can be increased with significant foreign investment. Iran produced 6 million b/d in 1974 but has not surpassed 3.9 million b/d on an annual basis since the Iranian revolution.

There is evidence that Iran may have maintained production levels and increased production at some key fields by using methods that have permanently damaged these fields.

Despite these issues, Iran has ambitious plans to double national oil production to about 8 million b/d by 2020. Over the next 4 years, Iran aims to double foreign investment in the hydrocarbons sector to $24 billion through controversial buy-back contracts.

Iraq, in spite of United Nations sanc tions, has been rebuilding war-damaged oil facilities and export terminals. Its sustainable oil production before the gulf war was about 3.5 million b/d. The gulf war caused severe damage to Iraq's oil industry, but the rehabilitation program has been extensive.

Iraq's oil infrastructure, developed over the past 65 years, is an elaborate network of many production centers with considerable flexibility. Thus, the restoration has proceeded relatively quickly, with some 80% of prewar oil production capacity reportedly restored. In 2000, Iraqi crude oil production averaged 2.8 million b/d. Iraqi officials had hoped to increase the country's oil production to 3.5 million b/d by the end of 2000, but they now have acknowledged that this was probably not realistic, given technical problems and some sanctions-related issues.

As in Saudi Arabia, Iraq's problem with "water cut" is a major challenge, especially in its southern fields. Iraq hopes to increase its oil production to more than 6 million b/d, following the lifting of UN sanctions. Iraq reported that, as of May 2001, it had signed several multibillion-dollar deals with foreign oil companies, mainly in China, France, and Russia, but sanctions have prevented these companies from beginning work.

In addition to 25 new field projects, Iraq plans to offer foreign oil companies service contracts to apply technology to 8 producing fields. Meanwhile, Iraq has authorized "risk contracts" to promote exploration in 9 remote Western Desert blocks. Iraq has identified at least 110 prospects in this region near the Jordanian and Saudi borders.

Political impacts

The costs to increase Middle East production capacity to the levels projected by IEA-would be extremely high-more than $150 billion for the region. No doubt such massive investments can be achieved only with the involvement of the international oil industry and perhaps the support of international multilateral agencies. The desire for this is shown clearly in Iran's and Iraq's existing development plans.

However, OPEC Middle East producers could decide, for many reasons such as the war against terrorism, that it would be in their economic interest if the enormous investments necessary to further increase oil production were not made. Then, as increasing demand forced up world oil prices, they would realize higher income from level production without more rapidly depleting their oil reserves, however large these may be.

In any scenario of increasing world oil production, Saudi Arabia would have to play a leading role. Any increase in world oil demand, on a scale envisioned by IEA, would require at least an additional 5 million b/d of oil output from Saudi Arabia, and that is even if countries such as Iran and Iraq fulfil their ambitious development plans.

Not insignificantly, Saudi Arabia's ability to fund an additional oil production increase of this magnitude is highly questionable. The country now runs a yearly deficit, and its monetary reserves are depleted. The faltering and badly managed economy has resulted in a somewhat reduced standard of living, record unemployment, an increasing homeless population, and some civil unrest. Many of Saudi Arabia's neighbors, especially Iraq and Iran, have been afflicted with similar maladies.

Since the Persian Gulf war, and especially after the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks on the US, the Saudi monarchy has been confronted with a growing Islamist movement that seeks to achieve a comprehensive transformation in the kingdom's social, economic, and political life.

Until the gulf war, most Islamist groups refrained from directly challenging the avowedly Islamic government. The gulf war transformed this situation by revealing the kingdom's weakness relative to Iraq and its dependence on US protection.

The fundamentalists' goals include an even stricter adherence to the "wahabbi" interpretation of Islamic law and practices, especially concerning the censorship of all foreign influences. Therefore, they would seek to significantly reduce the influence of the US and other Westerners in the area.

Above all, the impact of current US policy in the region cannot be underestimated, especially if it lasts for a significant time. It has resulted in increased instability for all the regimes in the region, pro-Western or not. This instability can only damage the environment for badly needed foreign investment.

Energy supply prognosis

Future hydrocarbon supplies will be constrained by how much the world can produce to meet demand. Supply will be determined by the ability to bring on stream technologically and economically challenging resources in deepwater regions and sensitive resources such as those in the Middle East.

We certainly don't believe that the world will run out of oil, but we believe that it could prove difficult to produce a significant share of the known proven reserves in selected regions to thus meet future demand.

If consumption were to stay relatively flat due to a sharp rise in oil prices, or if alternative energy sources were introduced, resource depletion could be delayed by several decades. However, under current and projected trends, world crude oil production will begin to fall within years, not decades.

Interestingly, IEA has indicated that its previous prediction for a decline in nuclear power has not been borne out, and as a result it has predicted increased reliance on this energy source in the coming decades. This, along with the growth of the natural gas market, bodes well for the future, but it is too early to tell if it will make up for the expected decline and possible shortage of future oil supplies.

Bibliography

OPEC Annual Statistical Bulletin, 2000.

Energy Information Administration, "World Energy Outlook 2000: With Projections to 2020," December 2001.

EIA, "Assumptions to the Annual Energy Outlook 2002," December 2001.

Cordesman, A.H, "Saudi Arabia Enters the 21st Century: Shaping the Future of the Saudi Petroleum Sector" (review draft), Jan. 3, 2002, Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), Washington, DC.

Cordesman, A.H., "The Shifting Geopolitics of Energy Fuel Choice, Supply, and Reliability in the Early 21st Century," January 2001, CSIS, Washington DC.

The Economist, "Anxious Times: Saudi Arabian Youth, " Sept. 9, 2000; "Saudi Arabia on the Dole," Apr. 22, 2000; "The Fatwa Against the Royal Family," Oct.13, 2001.

EIA country analysis, United Arab Emirates, accessed on Mar. 20, 2002.

EIA country analysis, Iran, accessed on Mar. 20, 2002.

EIA country analysis, Iraq, accessed on Mar. 20, 2002.

EIA country analysis, Kuwait, accessed on Mar. 19, 2002.

EIA country analysis, Saudi Arabia, accessed on Mar. 19, 2002.

Financial Times: "Survey-Saudi Arabia: Crisis poses no threat to supplies," Oct. 29, 2001; "Survey- Kuwait: Western energy giants are still waiting for invitations," Dec. 7, 2001; "Winds of Change," Feb. 10, 2002.

"Nigeria: Oil and Gas Ventures, Issues and Risks," unpublished paper, Houston, January 2001.

"Nigeria: An Awakening Oil & Gas Giant in the Gulf of Guinea: Upstream, Deepwaters, Regulations, Government, and Players," unpublished paper, Lagos, September 2000.

International Energy Agency, Oil Market Report, Paris, Mar. 12, 2002.

"OPEC-consumer cooperation needed to ensure adequate fuure oil supply," M. Takin, OGJ, Dec. 3, 2001, p. 22.

"Demand, supply will determine when production peaks," H. Parker, OGJ, Feb 25, 2002, p. 40.

Middle East crude oil trade: future directions and implications for formula pricing," FACTS Inc., OGJ, Feb. 18, 2002, p. 56.

Angola, Petroleum Economist, March 2002.

"Offshore NW Europe mature but offering opportunities for smaller players," J. Westwood, R. Knight, OGJ, Aug. 27, 2001, p. 58.

www.offshore-mag.com.

The Authors

Ivan Sandrea received his BS in geology from Baylor University in 1996. He then worked for BP PLC as an exploration geologist and commercial analyst in Venezuela and an operations geologist in Norway. Sandrea earned an MS in petroleum geology from Edinburgh University as well as an MBA with an emphasis on strategic issues affecting the oil and gas industry. In 2000, he served as gas market consultant to BP Egypt in Cairo. Sandrea's areas of focus include exploration potential of Latin America and Africa, effects of gas liberalization on the commercial framework of oil and gas companies, and exploration and production strategy. He has authored several publications and worked in collaboration with the geology department of Edinburgh University for studies relating to petroleum exploration. He currently is a research analyst for the oil and gas team at SchroderSalomonSmithBarney in London.

Osama Al-Buraiki is an Edinburgh-based consultant in the oil and gas industry. He received his BSc in mechanical engineering from the University of Petroleum and Minerals, Saudi Arabia, in 1994. In 1995, he joined Schlumberger Ltd. as an oilfield service engineer in the North Sea and has worked in Venezuela and Saudi Arabia. Al-Buraiki received an MBA from Edinburgh University with a focus on foreign direct investment in the Middle East oil and gas industry. His areas of interest include strategic issues in the Middle Eastern and Central Asian oil and gas industries, the impact of regional politics on the investment climate in these regions, and the prospects for information technology implementation in the oil and gas industry.