World markets speeding change for LNG shipping

Commercial LNG shipping is 40 years old this year, a significant landmark for some observers. While for most LNG participants, LNG shipping is merely a floating pipeline connection between producer and receiver, the stark reality is that this particular sector of the LNG industry is changing.

What most people don't quite acknowledge is the speed and extent of the change. And if there is so much change taking place, it is perhaps time to reassess LNG shipping's real function.

Brief history

When LNG was first shipped from Algeria to the UK in 1964, these were the only two ports in the trade. Algeria-to-France soon followed; then Alaska-to-Japan. The expanding Japanese market soon secured Asian supplies from Brunei and Indonesia. Abu Dhabi became the first Middle East producer to export to Japan.

Ships were dedicated to particular trades for specific business. While a few speculative vessels were built in anticipation of a growing market, the owners who did so faired badly.

There was tremendous anticipation 30 years ago for a growing US market, although this was cut short by deregulation of the natural gas market in the late 1970s. Ships that were destined for the US trade found themselves without employment and went into lay-up.

Four eventually went to scrap, three were converted into bulk carriers, and seven stayed in deep lay-up for nearly 20 years. Common sense would have suggested that the ships in lay-up should have been used in the new projects that started in the 1980s, but that was not the case.

The Japanese and Korean business was covered by new ships built in the East, and it was not until Nigeria LNG, an Atlantic Basin project that needed very competitive gas pricing to secure markets, that the laid-up vessels were put to very good commercial use.

Unfortunately, the pioneers from the LNG industry still influence how business is conducted, and as such they all remember the dark times of the mid- 1970s. In reality, however, what are the chances of history repeating itself?

ExxonMobil Corp. in Qatar is talking of another 30 million tons/year, Nigeria has about another 15 million tons, Australia has about 10 million tons scheduled, Angola had 7-8 million tons, Norway's Snohvit is considering a 5-million ton expansion, and the list is likely to grow.

The US is certain to have new LNG receiving terminals both onshore and offshore within the next 3-5 years, with US domestic production insufficient to satisfy market demand as this market continues to grow.

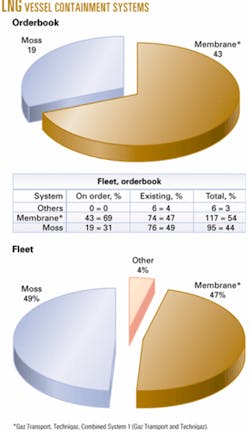

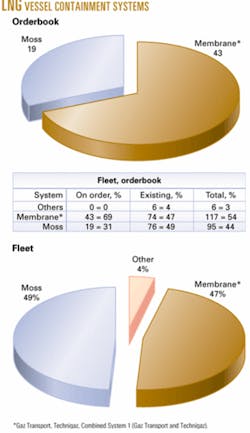

And shipping is crucial to LNG: The only reason natural gas is liquefied is to allow easy transportation by sea. Fig. 1 breaks down vessel containment systems.

Every ship that was contracted to a project always secured a 20-year charter or certainly matched the duration of the sales and purchase agreement (SPA), perhaps a reflection of the importance of securing shipping capacity

LNG shipping today

The world's LNG fleet stands at 156 ships afloat with an additional 62 on order for delivery by yearend 2007.

Vessel size has crept up slowly over the past 10 years with the largest vessel in the shipyard standing at 153,000 cu m. The most popular sizes lie between 138,000 and 145,000 cu m. The existing infrastructure at the terminals throughout the world has been designed for the existing fleet.

While there are numerous proposals for larger vessels up to 250,000 cu m, such vessels would need to be dedicated to specifically built new terminals. Under present Japanese restrictions, none of the large ships could enter Japanese or Korean ports, which at present represent about 64% of the market.

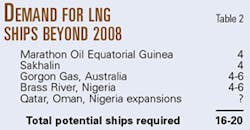

All of the vessels currently afloat are fully utilized, but for many of those that have entered service in the last 3 years, the trading pattern is extremely variable. The ton/miles carriage for some LNG ships is growing and likely to increase when new trains in the Middle East start up in 2007-08 for new business between Qatar and the UK and US (Tables 1 and 2).

Similarly all new vessels are designed to have the capability of going to every terminal (existing and planned) in the world with the possible exception of Everett, Mass., near Boston that has an air draft restriction under the Mystic Bridge.

This design issue alone gives us a good indication of how the trade is viewed for the future.

While in the past, 20 years was always considered a necessity for the period of the charter, we have seen over recent months that many charters are secured for considerably less time. New ships are being fixed from periods as short as 6 months through to 3-5 years, and some are still ordered against a 20-year charter.

But with shorter charters comes the opportunity to break away from the dedicated shipping perspective of only needing vessels for 20 years. Some gas buyers still negotiate 20-year SPAs and all sellers would try to secure such time frames, but there are a number of buyers who do not have their customers with back-to-back 20-year agreements. They then need to secure shorter contracts that in turn require shorter shipping commitments.

The arrival of new shipowners to LNG has heralded a new approach to charters, and we have heard from one new LNG owner who only wants to negotiate periods of less than 5 years.

Expansion

The world's fleet will expand by at least a further 70 ships, in addition to the 62 already on order, between now and 2010. Thus in 6 years the fleet will have almost doubled. Such rapid growth must put a strain on the human resources of the existing participants, and therefore more new shipowners need to be admitted into the "LNG Club."

In the past 6 months, Angelicoussis, Teekay, and Dynacom have joined, and there are market rumors that General Maritime Corp., Overseas Shipbuilding Inc., Tsakos Energy Navigation Ltd., and others are investigating the opportunities of joining. These owners at present run good fleets but lack specialist LNG knowledge. With correct instruction, however, this can be learned, as proven by BP PLC (1987 entrant) and Bergesen dy ASA(2003 entrant). Thus the new players can perform when trained.

The issue of larger vessels has been raised in relation to talks of expansion from Qatar and the requirements to ship cargoes over long distances to UK and US markets that render the transportation costs in the region of $1.4/ MMbtu. Tenders for these larger vessels are under way with results anticipated by the end of October 2004 (Table 3).

The timing of these tenders is unfortunate, however, as the shipping market is experiencing the upturn coupled with steel prices that are extremely high and placing yard prices under increasing pressure.

Thus the prices of January 2004 when the newbuilding price for a standard 138-145,000 cu m vessel was around $1,050/cu m is now about $1,150/cu m with a chance of rising further. If these prices are sustained, the 250,000-cu m vessel could cost $290 million.

While there is much excitement for the larger vessels, no one seems to be coming to grips with alternative propulsion. Gaz de France has two diesel-electric ships on order, one 74,000 cu m and one 153,000 cu m, but these are the only vessels on order that do not have steam-turbine propulsion.

The steam turbine consumes almost 200 tons/day LNG equivalent, while alternative propulsion can reduce this almost by half. The charterers, who are "kings" as in any sector of the shipping industry, do not seem too interested in this element of transportation costs, opting for the ever-reliable steam plant.

'Pipeline'?

As the world trade in LNG grows at an expected 10%/year and globalization of the trade seems unstoppable, the entire approach to dealing with LNG shipping needs to be addressed.

Projects have traditionally undertaken extensive tender processes, meddled with ship specifications, often on the whim of individuals in the technical teams, and generally "re-created the wheel" when it comes to LNG construction. There has been an obsession with longevity of vessels of up to 40 years or more along with other design criteria.

But is this all necessary when 17 ships on order are not yet committed to specific projects or when we have owners willing to charter vessels for short periods?

The vessels that have been delivered from the eight yards that currently build LNG carriers are all of excellent quality, performing their tasks per requirements.

Projects have usually excluded yards or owners from tenders due to lack of recent experience and thus the business has remained with the select few already in the Club. Recent events, however, have seen the spot trade accelerate, and projects have been taking new ships (for example, from the Spanish yard Izar) with new LNG owners for maiden voyages with pleasant surprises in terms of quality and competence.

As the industry matures, surely the time has arrived for a different attitude, and perhaps we can see the majors adopting a similar approach to how they secure tanker tonnage, for example.

With increasing numbers of ships and more trade routes developing, the opportunities for trading vessels improves. The obsession with ships for dedicated trades is an inefficient use of resources, and this is often reflected in projects that have insufficient shipping capacity to deal with over production or unforeseen spot cargoes.

The fleet needs some excess in order to permit the true development of the spot trade that in turn will reduce the "floating-pipeline" approach to shipping. Even one of the long-term players has forecast a reduction in long-term contracts to only 70% of world LNG trade by 2010. This could explain the need for Malaysian International Shipping Corp., Berhad, to order more ships for its growing LNG ambitions.

The author

Keith Bainbridge ([email protected]) has since 2001 served as director of LNG Shipping Solutions, London, a company created by a merger of LNG departments of the Paris brokerage firm Barry Rogliano Salles and Clarksons of London. He spent 15 years at sea with BP Shipping before, then worked for Lloyds' Underwriters and Elf, which seconded him to Nigeria LNG in 1995. He served as shipping manager for Nigeria LNG until November 1997 when he joined BRS. Bainbridge is a Class 1 Master Mariner.