COMMENT: EU energy investment drops as development obstacles rise

The European Commission, which aims to devise a “European strategy for sustainable, competitive, and secure energy,” published a green paper in March 2006 to that effect, suggesting that “Europe has not yet developed fully competitive energy markets.”

Energy is still regarded as a strategic sector in most European Union member states unwilling to relinquish their hold over the energy sector. Likewise, Europe’s major energy utilities are either state-owned or state-controlled. Under such conditions, new entrants often face many regulatory obstacles or political opposition.

Yet there is a more basic problem. Even when a company manages to find its way through the maze of protectionist hurdles, a mix of local vetoes, environmental opposition, and bureaucratic confusion increases the cost of investment, either in monetary terms or in the disproportionate amount of time and effort needed to satisfy all administrative and legal mandates such as ever-stricter environmental requirements.

Hence the size and effectiveness of investments are tending to decrease, while the efficiency of the energy sector as a whole decreases. Meanwhile demand continues to grow.

Greater investment is needed to meet the growing demand, heighten competitive pressures over incumbents, and to replace ageing facilities. It is also needed to strengthen cross-border ties and to phase out fuels currently used in Europe’s power plants, such as the shifting from crude oil to gas or coal.

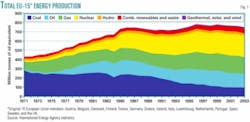

Figs. 1 and 2 illustrate the challenge Europe is facing. Total energy production in the 15 original member states rose by almost 80% during 1970-85 (Fig. 1). Then the rate of growth slowed to the current level, which is slightly above that of 20 years ago. Since the early 1970s, the share of coal has dramatically decreased, whereas nuclear power, oil, and gas use have all gained momentum. The reliance on imported energy sources has grown to 50% of total consumption and is expected to increase again-to 65% in 2030: That means natural gas imports will grow to 84% from 57%, and oil imports will increase to 93% from 82%.

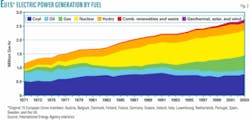

If one looks at electric power generation, the figures speak for themselves. The amount of generated electricity has more than doubled since the 1970s, and the upward trend shows no sign of slowing down or reversing course (Fig. 2). The amount of electricity generated by coal has been about the same since the early 1980s, with a slight increase across the 1980s, a slight decrease in the 1990s, and another increasing stage as oil prices started to surge in the 2000s. Nuclear power increased dramatically until some 20 years ago, and oil use shrank as gas gained momentum.

The increase in demand for electricity, as well as the threats to energy security due to the opportunistic behavior of some producing countries and the shift from coal and oil to gas-based generation, have made investments to improve energy security both a political priority and an economic necessity. Given the vital importance of energy to a modern economy, the search for security or the unreliability of energy supplies keeps companies from investing and prevents the economy as a whole from becoming more competitive.

Likewise, from a political point of view, the failure to create an environment of maximum energy security would cast a shadow on the EU’s ability to address the very basic needs it is charged with handling. Yet Brussels hasn’t been able to implement a consistent energy policy because, under the European Treaty, it hasn’t the power to make binding decisions on the issue. In this respect, it is unlikely that any significant change will occur, as most member states consider energy to be a national security priority and would not be willing to give up their sovereignty over the energy sector.

Suggested solutions

Nevertheless, there is a way for the EU to improve energy security effectively without directly affecting it-that is through liberalization. By promoting liberalization-removing barriers to market entry and fighting nationalistic claims and attempts to prevent foreign takeovers of energy companies-the commission may help the European energy sector become more flexible and better equipped to react to shocks.

In a March-April 2006 article in “Foreign Affairs,” Cambridge Energy Research Associates Director Daniel Yergin argued that markets themselves are a source of security. Yet a well-performing regulatory framework is not enough. As Yergin puts it, “The investment climate itself must become a key concern in energy security. There must be a continual flow of investment and technology in order for new resources to be developed.” In other words, the most basic need Europe is facing is a host of companies willing to invest and be able to draft projects that meet all of the environmental and regulatory requirements. That is not always possible.

For example, environmental organizations-while officially standing for energy security-often pursue policies that would result in the opposite outcome. The organization Friends of the Earth, for one, claims it seeks to cut Europe’s energy consumption by 20% by 2020 and to have renewables meet 25% of primary energy demand by then. Neither is consistent with the target of energy security. Indeed the former is inconsistent with reality, as energy consumption worldwide is always growing, while the latter implies a greater reliance on more-expensive sources of energy. While Friends of the Earth may look like an extremist pressure group, its goals are more or less openly shared by many inside the EU.

However, as Leonardo Maugeri said in his book, The Age of Oil, “In the real world, the replacement of a resource with another is driven by economics, not by politics.” It looks as if the EC and its environmental stakeholders have not fully realized this latter point. A communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, released as recently as Jan. 10, sets the goal of increasing the level of renewable energy in the overall EU mix to 20% in 2020. What is more relevant is not that such a goal is utterly unrealistic. By following such a course, emphasis is shifted away from what really matters, allowing-or better yet promoting-investments in reliable, economically efficient resources and technology that are already available.

The commission well knows that the real problem is not really renewables development but how to achieve a higher degree of energy security. In its communication, it also calls for more effective regulation, ownership unbundling in the electricity and gas sector, and more investments in energy infrastructure. The paper estimates that the EU will have to invest €900 billion on new electricity generation alone in the next 25 years. However, by mixing climate alarmism, unrealistic targets, and sound policies, the commission can hardly be said to be making a fair assessment of the situation-and an unfair assessment is unlikely to lead to a meaningful solution.

The Italian case

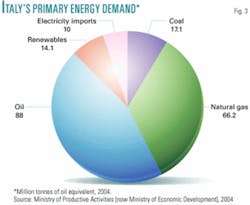

In this respect, the Italian case is particularly interesting. For both political and economic reasons, the country has shifted from oil to gas as its major source for electric power generation. Gas also is the most important fuel for heating. Domestic oil consumption is driven almost exclusively by the transportation sector, while coal plays a smaller, although slowly growing, role. Finally, nuclear power was banned after a referendum in 1987.

Fig. 3 shows Italy’s primary energy needs by source. In 2004 annual oil demand fell to 88 million tonnes of oil equivalent from 91.2 in 2001-down 3.5%-whereas gas demand rose 13.2% to 66.2 million tonnes of oil equivalent from 58.5 during that time. Total energy demand rose by 4.1% in the same years.

Because Italy has small and declining domestic gas production of only 13 billion cu m/year, it relies on imported gas for an additional 66.2 billion cu m (in 2004). Of the imports, 30.6% comes from Russia and 29.7% from Algeria. Since the early 2000s the country has gone through electricity and gas crises due to weaknesses in the power grid, lack of generation capacity, and insufficient import capacity. Today regulators and industry personnel are crossing their fingers in hopes the winter will remain mild, keeping gas demand relatively low. Virtually everyone agrees that import capacity should be boosted by building LNG terminals and laying additional pipelines or increasing the size of existing lines.

Just one LNG regasification terminal exists in Italy. Operated by Eni SPA, it has a capacity of 4 billion cu m/year compared with demand of 86 billion cu m in 2005. Eleven projects for LNG terminals have been submitted for authorization, two of which-in Rovigo and Brindisi-have been authorized and four that are expected to receive final authorization soon.

The authorization process for Rovigo began in 1997 when the terminal was planned to be onshore. However opposition of local groups was so vocal that it convinced Edison Gas SPA, the company in charge of building the terminal, to move the projected facility offshore. In the meantime, Edison formed a partnership-Edison 10%, ExxonMobil Corp. 40%, and Qatar Petroleum Co. 40%-to build and run the terminal.

Local governments still held that the terminal was harmful to the environment and to the local economy, particularly to tourism. The legal battle is continuing, even though the companies involved have consistently won, and construction of the terminal has begun. Because of high legal costs and increased expenditures associated with building it offshore, the terminal costs more than doubled-from €450 million to €800 million and then to the latest estimate of over €1 billion. As far as the timing is concerned, it took almost a decade to get authorizations for a terminal whose construction will require 2 years. The terminal was to become fully operational in 2008 if no further obstacles were encountered. Unfortunately, on Sept.18, 2006, when the regasification plant-which was being built in Spain-was 50% complete, construction was stopped for an apparent lack of authorization for a secondary, temporary structure, and a new legal battle began.

The Brindisi project is in a much worse predicament. The €400 million regasification plant, on which €150 million has already been spent, received its “definitive” authorization in 2002, but it is still unclear whether prospective operator British Gas will ever be able to actually build it. In an interview with Il Corriere della Sera, Italy’s most influential daily magazine, on Sept. 11, 2006, Nichi Vendola, head of the regional government of Puglia, where Brindisi is located, said the plant obtained approval of both the Brindisi City Council and the Puglia regional government, along with 21 other governments or agencies, but “thereafter the administrations were kicked out of office.” Vendola said, “ That means that their decisions didn’t satisfy local populations. Hence they have to be changed. It is not by chance that current administrations have been voted precisely because of their opposition to the LNG terminal.”

As to the other submitted projects, most of them are unlikely to be built. That leads to the paradox of a virtual oversupply of gas vis-à-vis a gas scarcity, as former Industry Minister and Editor-in-Chief of the specialized magazine Energia Alberto Clò, wrote. The same may be said of electric power generation. For example, Enel has been struggling for months to convert an old oil-fueled plant into a more-efficient coal-fueled facility. The delays again result from legal actions and political opposition from local and regional governments.

Even when the authorization process was faithfully followed, local, provincial, and regional governments, as well as environmental or consumer organizations and other pressure groups have filed lawsuits, known to be lost in advance, that can be used to stop work in progress and increase monetary and time costs. Hence, they become a disincentive to investors, as the real cost of investments in such a crucial sector as energy is significantly increased.

A way out?

Italy’s problem-which is partly shared by other EU member states, but which in Italy reaches an unsustainable level-is twofold: On one hand, local populations scarcely involved in the decision-making process and who gain almost no benefit from it have an incentive to oppose any project.

On the other hand, the decision-making process is too confused, and too many subjects hold a de facto right to veto any decision. For example, in the case of Brindisi, 23 different subjects have been involved in the decision-making process.

A recent piece of incentive legislation promoted by Minister of Economic Development Pierluigi Bersani moves in the right direction: It would reduce the level of energy taxation for those communities that allow a power plant to be built in their territory. While the attempt to create an economic incentive to oppose the NIMBY (not in my back yard) effect is a good move, it is not enough. Other amendments in the current legislation can help to make more socially acceptable those plants that are required to strengthen Italy’s energy security.

- Companies should be allowed to sell electricity or gas to local consumers at a discounted rate to increase the economic incentive. Such discounts should be tax-deductible for the companies.

- A principle of “administrative continuity” should be enforced: Once an administration has given its approval to a project, it shouldn’t be allowed to reverse the decision, even when the governing coalition changes after elections.

- When an authorization is released, a mandatory period of 180 days should be left for those who still have complaints to seek an adjustment with the operating company. If a negotiation round is made possible and compulsory, the parties might find it more convenient to take advantage of it, rather than assuming the costs of litigation.

- After authorization becomes effective, it should still be possible to file appeals, but they should not be allowed to stop work in progress except for the most serious reasons. It should be up to the company to choose between going on and stopping temporarily-if the company knows that the appeal is just a pretext to delay the work, then it could resume construction.

What Italy and the rest of Europe need is not revolutionary change, but common sense amendments to current legislation. A recent survey by the World Bank shows that, as far as ease of doing business is concerned, Italy ranks 82nd, down from 69th in 2005. In terms of licensing procedures, it ranks 104th. To secure the necessary licenses to start a business, an Italian company needs, on average, to clear 17 procedural hurdles-as opposed to an Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) average of 14-to wait for 284 days (149.5 in OECD) and to spend 142.3% of per capita income (72% in OECD).

The consequence is that Italy’s energy system is weak, and an energy crisis is always looming. This is not about a lack of capital or companies willing to invest in the country. This is because of perverse incentives that are set up by an overwhelming, confused, antimarket regulatory environment.

The author

Carlo Stagnaro ([email protected]) is environmental director of Istituto Bruno Leoni, Italy’s free market think tank, and a fellow of the Brussels-based International Council for Capital Formation. He received a degree in Environmental Engineering from the University of Genoa. Stagnaro has written extensively on environment and energy issues, including global warming, energy and climate policies, liberalization, and privatization in the energy sector. He is a regular contributor to the Italian daily magazine Il Foglio (Rome), and his articles have been published in a variety of newspapers, including Energia (Bologna), Il Riformista (Rome), and Economic Affairs (London).