US upstream jobs rose in 2004, data show

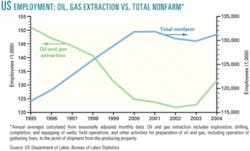

Employment in the US upstream oil and gas industry gained along with total nonfarm employment for the first time in many years in 2004, preliminary data show.

While the number of US nonfarm jobs has mostly increased in the past decade, oil and gas extraction jobs fell steadily until 2002. After gaining slightly in 2003, when nonfarm jobs declined, the annual average oil gas total, calculated from seasonally adjusted monthly data reported by the Department of Labor's Bureau of Labor Statistics, jumped along with nonfarm employment last year (see figure). Data for last November and December are estimates.

Oil and gas employment trends haven't tracked activity indicators, such as rig counts, well in recent years—a phenomenon that industry officials attribute to problems with the data and major changes in practice during the past decade.

The trends

Despite the apparent annual increase, December's oil and gas extraction employment declined by 300 from November's level to an estimated 133,200 jobs, 6.9% more than the sector's 124,600 jobs in December 2003.

December's estimate was almost 15% lower than January 1995, when BLS listed 156,300 oil and gas extraction jobs.

Jobs in that category declined in 64 of the 94 months from January 1995 to October 2002, when BLS reported 120,000 oil and gas extraction positions, a 10-year low. Then they began a steady recovery, growing in 20 of the next 26 months to 133,500 positions this past November.

Total nonfarm employment rose for a 16th consecutive month in December with the addition of 157,000 jobs. The month's total was an estimated 132,266,000—1.7% more than in December 2003 and 5.4% higher than August 2003, just before the current economic recovery began.

Jobs and activity

The employment numbers don't correlate directly with domestic oil and gas prices, production, drilling activity, or other indicators of industry activity between January 1995 and December 2004.

Gary R. Flaharty, director of investor relations at Baker Hughes Inc., which tracks active rigs, observes, "The long-term trend was increasing activity as employment numbers decreased. The two sets of numbers started to move in similar directions from 2003 through 2004."

He points out that industry employment data reflect more types of activity than what is associated with simply drilling a well.

BLS defines oil and gas extraction as "industries that operate and develop crude petroleum and natural gas properties. Industries include exploration for crude petroleum and natural gas; drilling, completing and equipping wells; operating separators, emulsion breakers, desilting equipment and field gathering lines for crude petroleum and natural gas; and all other activities for the preparation of crude petroleum and natural gas up to the point of shipment from the producing property."

Ed Porter, research manager at the American Petroleum Institute, sees voids in the data.

"The Labor Department only covers that part of the job force that's covered by unemployment insurance and does not include any individual proprietors," he says. "That can leave out as much as half of some parts of the industry, such as independent producers. We've found that to be the case in some of the states."

Porter also notes that the Labor Department reports jobs overall instead of full-time positions.

"That means that part-time employees are included," he says. "Consequently, if more part-time positions replaced full-time slots, it would not be reflected."

The API official suggests that the BLS numbers might reflect a significant change in the last 10 years.

"In the mid-1990s, a lot of the activity was dominated by offshore activity, where fewer people were used," he says. "Since then, it has moved more to onshore areas like the Rocky Mountains, where it is more labor-intensive. Offshore and onshore drilling use different technologies with different labor requirements. That might be some of what we're seeing here."

Fewer employees

Independent producers, whose share of total domestic exploration and production grew as major oil companies moved overseas, generally use fewer employees at the wellsite.

"I don't believe the average independent's work force has grown that much," says Frederick Lawrence, vice-president of economics and international affairs at the Independent Petroleum Association of America.

Three-dimensional seismic surveys, horizontal drilling, robotics and other technologies have allowed independents to successfully revisit fields that were considered mature previously, he notes.

"There's also been a lot of infill drilling, which hasn't required the number of employees necessary to drill a new well. But producers still call on geologists, geophysicists, and other specialists to help them find and identify deposits in increasingly complex formations."

They also need drilling crews, which aren't always readily available, says Brian T. Petty, senior vice-president of government affairs at the International Association of Drilling Contractors.

"Today, we are finding shortages with rig hands, especially in the Rocky Mountains," he says. "We have areas in Wyoming and North Dakota where the rigs simply can't go to work. At this time, demand simply exceeds the supply of good, trained hands."

IPAA's Lawrence says, "It's particularly intensive in the Rockies because drilling often takes place in remote, desolate areas where it can be hard to get people to relocate. That's why there's an effort under way to train people who already live in those communities."

As the general economy improves, however, it's difficult for drilling contractors and other oil and gas firms to attract employees and guarantee they'll still be working 2 years from now, Petty says.

"The industry has had two severe busts, where world oil prices have dropped to $10[/bbl] or below, in the past 20 years. There were massive layoffs and consolidations. We may be emerging from that because world demand seems to be growing inexorably," he says. "We have a lot of iron wanting crews."