Applied geophysics archives

To the world at large, geophysics is the field of science that enables mapping of earthquake-prone fault lines, unearthing of ancient artifacts, planning of a bridge, or hypothesizing the origin of a meteor. To readers of Oil & Gas Journal, geophysics is the definitive tool for understanding the complicated geological architecture of hydrocarbon-bearing strata.

From the primitive tools of the 1920s to the massive computer-imaging power of today, geophysical applications have challenged and fascinated those drawn to this field.

Some old-timers may remember a few tools used by past geoscientists.

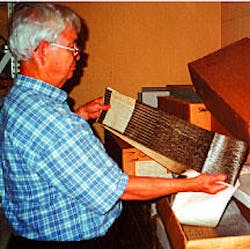

This editor browsed through the Geophysical Society of Houston (GSH) archive storage, courtesy of Hays Infor- mation Management Inc., Houston. Tom Fulton, seismic consultant for Seismic Solutions Inc., Chesterfield, Mo., and past president of GSH, led the search through shelves of boxes to uncover documents and equipment dating from the 1920s to the 1970s.

Archaic equipment

One box revealed a torsion balance gravimeter, equipment used to provide evidence of different densities of the subsurface. In the 1920s, before reflection seismic technology, a reading of low density might indicate a salt dome, a primary target in the search for oil after the fam- ous Spindletop gusher.

Another box held a recording oscillograph, first used around 1930, which made visible seismic records on photosensitive paper. A camera-mirror device reflected a small beam of light that traced out seismic figures on the paper.

Magnetic tape, dated 1965 and after, showed the steady progression of other methods of recording seismic data before the advent of digital recorders.

As the recordings became more sophisticated and complex, problems arose. One of the early problems caused by increased complexity was the advent of "ghost images."

"A ghost image, or surface reflection, is caused by energy from a buried, explosive charge that travels up, is reflected from the surface, then travels back down," explained Fulton, "and that type of spurious noise must be eliminated."

Later, a broomstick charge was designed to reduce and virtually eliminate ghost images from onshore shot hole seismic operations. The charge was designed to match downward velocity of the formation to create a directional seismic wave front able to yield high frequencies. The goal: Eliminate the ghost by reducing the upward traveling energy.

Language of the past

Even the language differed from today. A yellow-paged comic book, penned by Bob Schoenke, explained that a "doodlebugger" was a person usually seen carrying a mysterious black box and checking various ground sites for natural gas leaks or other anomalies that might indicate a pay zone. The "birddog" checked the progress of the seismic crew, and a "noodlehead" loaded shot holes. "Jug hustlers" weren't moonshiners but men responsible for precise placement of geophones.

Buried under a spaghetti pile of cables and eroded wires, a lower shelf revealed a Monroe calculator, circa 1930, used for mathematical formulas and square root calculations. Operating a Monroe calculator consisted of pushing buttons and turning a crank handle.

My favorite find was a well-preserved and intricately detailed miniature thump- er truck, complete with guide chains and electronic controls. Thumpers were widely used in West Texas, Africa, and the Middle East during the late 1950s and for several decades thereafter in some areas. A thumper provided seismic energy produced via a three-ton steel plate dropped from a cable at the rear end of the truck. The returning signals were recorded on magnetic tape for later analysis. An updated version of this approach is detailed in an article, part of this issue's Applied Geophysics special report, that begins on p. 76.

More collections

More collections of these types of artifacts are available for public viewing in the Winship Building of North Harris College in Houston and at the Bob Bullock Texas State History Museum in Austin.

To attract and enthrall new generations, the Society of Exploration Geophysicists, Tulsa, will open its Geoscience Center at its headquarters on Oct. 11. Using unique, interactive exhibits such as the "LenaSeis," a seismic portrait of the visitor, and other demonstrations of cutting-edge technology, the center aims to engage people of all ages. A traveling museum with hands-on earth science activities targeted to fifth to twelfth-grade students is available to Tulsa-area schools. More information is at SEG's web site at www.museum.seg.org, or [email protected].