Bob Williams

Senior Staff Writer

Only Alaska and California can make a sizable near term contribution to boosting U.S. oil production.

In terms of current reserves, all other U.S. oil producing states combined could not ramp up production enough in 1 year to make much of a dent in the natural decline in U.S. oil fields (OGJ, Sept. 17, p. 21).

Even with a strong effort from Alaska and California added, the U.S. would at best trim the rate of its oil production decline in 1 year.

With sustained higher oil prices and fast track permitting, however, the two states could make a significant difference in U.S. production in a 5-10 year span, based on undeveloped oil reserves.

1995 OUTLOOK

Judging from responses to a survey of producing states by the Interstate Oil Compact Commission, even a sustained oil price increase through 1995 would have little effect on U.S. ability to increase oil production from current levels.

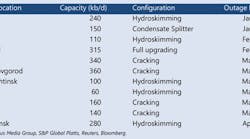

Survey responses suggested the U.S. could hike oil flow by about 360,000 b/d in 1 year. However, respondents did not mention taking into consideration field decline rates, which probably would peg the net gain in 1 year at less than 20,000 b/d. Further, some assumed sustained higher oil prices and restoration of all shut-in production. The exceptions for the 5 year outlook, again, are Alaska and California, where more than several billion barrels of reserves remain blocked from development by environmental or economic reasons or a combination of both (Table).

That does not include the speculated huge potential of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge Coastal Plain on Alaska's North Slope or off northern California, both currently off limits to drilling. Even if drilling were allowed in those areas, production probably could not go on stream before the end of the decade.

The rest of the U.S. Outer Continental Shelf might also contribute to U.S. oil production some day, but leasing bans and technological constraints will push that contribution into the next century. An exception to that rule is the Gulf of Mexico deepwater play, where the potential for finding giant oil and gas fields is fueling a flurry of drilling (OGJ, June 4, p. 64).

However, it is California's offshore and Alaska's North Slope and nearshore Beaufort Sea that offer the biggest identified reserves capable of being placed on production in this decade.

NUMBERS DON'T ADD

The IOCC survey and industry responses to the question of where the U.S. could ramp up oil flow quickly in a crisis apparently conflict with estimates by the Department of Energy that if U.S. producers are given certain fiscal incentives, U.S. oil production could jump by almost 200,000 b/d by 1995 (OGJ, Sept. 24, p. 56).

Assuming suspension of production allowables, a sustained higher oil price of about $25/bbl in 1991, and restart of half or more of shut-in stripper production, the U.S. could boost oil flow by 424,280 b/d within 1 year, IOCC survey responses showed. However, only Alabama and Nevada specified their estimates as net gains from current production.

Assuming a natural field decline of 5% from OGJ,s projected U.S. production of 7.2 million b/d in 1990 otherwise yields a drop of 360,000 b/d. Using the IOCC survey responses, that leaves the net gain in U.S. oil production in 1 year at about 60,000 b/d.

OGJ estimates the gain from a best efforts response would more likely be only about one fifth that level.

But a best efforts response is not likely, given the decimation of the U.S. oil service and supply sector, uncertainty over oil prices, and limited capital. So OGJ instead projects a fall in U.S. oil production in 1991 of about 145,000 b/d from projected 1990 levels. Using a hypothetical projected decline rate of 5%/year, the U.S. could otherwise be expected to lose about 1.6 million b/d of production during 1990-95. That compares with a loss of almost 1.9 million b/d of production in the Lower 48 in 1973-85, a span that covers two periods of big oil price jumps.

U.S. gains in oil production during the 1970's and 1980's came essentially from Alaska. In 1973-85, even with expectations of indefinitely higher oil prices and a record drilling surge, Lower 48 oil production could muster gains of only 0.3% in 1983 and 2.6% in 1984 before slipping into decline again. Further, Alaskan North Slope oil flow, which had softened the Lower 48 slide, is now in decline.

So for a net gain of 200,000 b/d by 1995 from 1990 levels, the U.S.-without a 2 million b/d surge in Alaskan flow-would somehow have to hike gross production by as much as the Lower 48 lost in 1973-85. And that was when the oil industry infrastructure had built to unprecedented levels, not lying in tatters after 4 years of industry depression.

In fact, the government earlier this year projected U.S. crude and lease condensate production in 1995 at 6.34 million b/d under a base case forecast by DOE's Energy Information Administration. In its midyear forecast, OGJ estimated U.S. crude and condensate production will fall 5.2% in 1990 from 1989 levels. OGJ estimated U.S. crude/condensate production slipped 5.7% in 1989 from the year before.

ALASKA

Alaska, with three of the six biggest U.S. fields in terms of production, can account for more than half of the 1991 U.S. production increase covered by IOCC survey responses.

By early 1991, the North Slope could hike production about a net 125,000-170,000 b/d-after accounting for Prudhoe Bay's natural decline-from levels in early 1990, North Slope operators said. The increases would come mainly in Prudhoe Bay field, where gross production would jump about 225,000 b/d from a 1990 low of about 1.1 million b/d in early September.

In addition to Prudhoe Bay's natural decline, production in the giant field fell about another 100,000 b/d in the summer because of operating inefficiencies in warmer weather and to accommodate tie-in of facilities for Prudhoe Bay's gas handling expansion (GHX) project.

Partly because of the downtime, affecting five of six flow stations and temporary shutdowns of the central gas facility, Prudhoe Bay has averaged only about 1.3 million b/d so far in 1990 vs. 1.45 million b/d in late 1989.

BP, ARCO VIEWS

BP Exploration (Alaska) Inc. says North Slope production could jump by about 70,000 b/d of oil before yearend.

Of that total, more than 50,000 b/d would come from an accelerated hydraulic fracturing program in the east and west sectors of Prudhoe Bay field. North Slope operators had earlier planned 80-100 frac jobs in Prudhoe Bay for 1990. After DOE officials asked them to push up production, operators jumped that program to 130-140 frac jobs for 1990.

BP says fracking a Prudhoe Bay well can quickly boost its flow by 100-500%.

Of the remaining expected increase, Endicott field would provide about 10,000-12,000 b/d in addition to current flow of about 100,000 b/d. Sag Delta, a satellite to Endicott, is expected to increase to 10,000 b/d from 4,000 b/d, BP said.

Increasing gas handling capacity with GHX-1 would add a further 90,000-1 00,000 b/d to North Slope production. BP thinks the project could be on stream by late this year or early 1991.

ARCO Alaska Inc. also estimates accelerated fracking will boost Prudhoe flow by 50,000 b/d and expects GHX-1 to add 75,000 b/d of production by early 1991.

"At Kuparuk River and Lisburne fields, we are essentially at capacity," an ARCO official said. "We were doing everything possible to lift as much oil as we could in those fields before the Middle East crisis. "

OTHER NORTH SLOPE POTENTIAL

Capacity to boost North Slope production further in 1991 or beyond in the near term is limited.

A principal concern is pipeline capacity. Tests of drag reducing agents have shown the Trans-Alaska Pipeline System throughput could be pushed to more than 2 million b/d, but it is not certain how long that could be sustained.

BP rebuffed suggestions that flaring gas might provide a quick jump in North Slope oil production. The concern here is the threat of losing reserves in the long term by not maintaining reservoir pressure with gas injection. In addition, there is the loss of the gas itself, which could become a valuable commodity if a feasible market emerges for North Slope gas.

The best midterm prospects for hiking North Slope oil flow as Prudhoe Bay declines remain hamstrung by economic or environmental concerns.

In addition, there are state severance tax considerations that raise other questions about the economic feasibility of any new development in Alaska. BP earlier shelved an $80 million development project, Hurl State in the west end of Prudhoe Bay field, because of changes in Alaska's severance tax calculations approved after the Exxon Valdez tanker spill.

Those fiscal questions and environmental issues don't bode well for developing other North Slope reservoirs, such as West Sak, Seal island/Northstar, Colville Delta,

Gwydyr Bay, and Point Thomson-Flaxman Island (OGJ, Sept. 25, 1989, p. 27).

The two "developed" fields DOE has pointed to as contributing 100,000 b/d in 12-18 months, Niakuk and Point McIntyre, in fact remain undeveloped because of economic and environmental concerns.

NIAKUK FIELD

BP has asked the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to suspend action on its permit for proposed development of Niakuk oil field.

Even if economic and put on a fast permitting track, the field could not start up before 1992-93, BP said. The 58 million bbl Kuparuk River sands reservoir in shallow waters west of Endicott field could produce as much as 20,000 b/d.

Fine tuning the project's engineering design led BP to realize Niakuk development would require considerably more gas handling and compression than was earlier expected. That meant increasing the number of production modules to 35 from 15 for the marginal project and a jump to $250 million from $130 million in capital costs. At that price, Niakuk economics no longer seem attractive, BP said.

"A few weeks of higher prices is obviously not going to change our long term outlook for oil prices," a BP official said. "But even if prices remain high, every other prospect looks more attractive, too. There has to be a list of priorities, and Niakuk at $250 million is not very high on that list."

BP currently is looking at the possibility of bringing in partners for the project or, if reasonable fees can be obtained, sharing production facilities in Lisburne field.

POINT MCINTYRE

Environmental concerns hamper the other attractive midterm chance to boost North Slope production. ARCO had hoped to have Point McIntyre field on stream by late 1992 or early 1993.

However, its Army Corps permits are stalled by Environmental Protection Agency opposition. EPA opposes a critical aspect of Point McIntyre, a drillsite on Prudhoe Bay's West Dock,

EPA wants the West Dock drillsite permit denied unless ARCO agrees to a breach in the dock causeway to allow unfettered passage of marine life. Beaufort Sea causeways have been a focus of controversy for a number of years.

ARCO insists the drillsite permit and the West Dock causeway are separate issues and should be treated as such.

Although ARCO has not estimated Point McIntyre peak production, the field conceivably could be tied into Lisburne field facilities to take advantage of perhaps 80,000 b/d of excess capacity. However, Niakuk also is a possible candidate for development through Lisburne facilities.

The state Department of Natural Resources' Division of Oil and Gas estimated in January 1990 Point McIntyre production would start in 1992 at 20,000 b/d and peak at 60,000 b/d in 1993-95.

CALIFORNIA

IOCC survey responses showed California could hike oil production by 225,000 b/d by 1995. That assumes, however, that giant Point Arguello field is producing at peak by then.

Although California has a substantial amount of shutin productive capacity, the state's decimated service sector prevents it from ramping up production significantly in the near term.

Low oil prices have left more than 14,000 wells idle in California for 5 years or more, says Marty Mefferd, the state's oil and gas supervisor.

"A lot of the wells are sitting there with production equipment intact," he said. "A number of those are still hooked to pumping units, and we're trying to get them started. For a lot of them, that just means pulling rods and tubing, And there are a lot of steam generators shut down. For a lot of the wells and steam generators, the permits are already in hand."

Most of California's crude oil production is low gravity and thus especially sensitive to oil price declines. As a result, with expectations of higher oil prices in the 1990's gaining strength earlier this year, operators have rushed into infill and workover programs in California in recent months.

The state has undergone a sizzling pace of new wells, workovers, and abandonments. The workovers and abandonments are spurred in part by the state's tightening rules on idle wells. Even before the Middle East crisis, many California operators were running economic litmus tests of their shutin wells forced by the tighter idle well rules and finding more of them passing the test than they had expected.

"We were starting to see some stability in prices," Meffered said. "Major operators decided they weren't going to fool around with offshore California any more and started to put their money in proven areas.

"With $20/bbl for Kern River (13*) crude, we're going to see some of that production we've lost since 1985."

Mefferd puts that production decline at about 150,000 b/d. It entails mostly shutin stripper wells in areas of very low gravity crudes such as the onshore Santa Maria basin and shutdown thermal enhanced oil recovery projects in the southern San Joaquin Valley.

"We're reasonably sure 75% of that can come back on stream in 1-11/2 years-maybe 75,000-100,000 b/d within a year," he said.

The state does not have the capability to speed that process because of heavy losses among drilling and service rig contractors.

"A lot of contractors have gone out of business," Mefferd said. "If you want to work on a well, you have to get on a waiting list, even to get a well abandoned."

ENVIRONMENTAL BARRIERS

Beyond the infrastructure constraints and uneasiness about future oil prices, California operators are hamstrung by environmental concerns as well.

In addition to bans on further leasing off California, operators continue to be plagued by environmental opposition to development of 1980's discoveries-some of them giant fields-in the offshore Santa Maria and Santa Barbara basins.

Of those projects not on stream today, only Exxon Corp.'s further development of Santa Ynez Unit is moving ahead.

Earlier estimates of California offshore production in the 1990's climbed to as high as 500,000 b/d, although that assumed the unlikely prospect of concurrent development. More recent estimates place that level at about 200,000-300,000 b/d.

Outside the San Joaquin Valley, there is little prospect for increased production in California.

"The industry has given up on the Los Angeles basin," Mefferd said. "There are so many constraints there it is too much overcome. With the current political climate, nothing is going to change in state waters, either."

On the other hand, says Mefferd, the Middle East crisis has sharply focused Californians' attention on energy security issues, a development that might provide some long term support for drilling off California.

He cites the most recent statewide poll in California that shows opposition to offshore drilling has fallen by 910 percentage points since the Iraqi invasion.

Copyright 1990 Oil & Gas Journal. All Rights Reserved.