Turkish Stream offers Russia increased export control

Elmar Baghirov

Azerbaijan Diplomatic Academy

Baku

Estimates have the European Union importing 49% more gas in 2035 than in 2012.1 Russia would like to secure as much of this market as possible. Before pursuing the South Stream natural gas pipeline project, OAO Gazprom in 2002 proposed Blue Stream II, paralleling Blue Stream across the Black Sea to Turkey.

Five years later, however, Gazprom announced South Stream, a project that would bypass both Ukraine and Turkey. On Dec. 1, 2014, after visiting Ankara, Turkey, Russian Pres. Vladimir Putin cancelled South Stream and instead put forward a new 63 billion cu m (bcm)/year pipeline intended both to meet growing Turkish demand and to supply gas to southern Europe.

The proposed pipeline is much shorter than South Stream and therefore more affordable. Gazprom Chief Executive Officer Alexei Miller immediately began advising that the European Union (EU) should start building a gas transportation network to the border with Turkey, in a move designed to make it clear both that South Stream was dead and that Russia still intended to supply the EU with natural gas (Fig. 1).

South Stream's end

The EU pressured its member states to refuse the project, describing it as in conflict with the EU's Third Energy Package (TEP) as regarded third-party access and ownership unbundling. Russia expected an exemption, based on the idea that the project was of high strategic importance to EU energy security, but never actually applied for it.

Gazprom had earlier expressed its willingness to use the Nord Stream pipeline's onshore extensions-Ostsee Pipeline Link (OPAL) and Northern European Natural Gas Pipeline (NEL)-to full capacity. But the European Commission's (EC) Competition Authority limited Gazprom's access to 50% despite Germany having already granted an exemption. The EC ended its OPAL exemption review in December 2014, citing Gazprom's failure to extend the deadline by which it needed to formalize its exemption with the German regulator.2

Rather than pursue a similar exemption for South Stream, Gazprom instead decided to sign intergovernmental agreements (IGA) with the line's individual host countries. The EC deemed these agreements in breach of the TEP and called for their renegotiation, threatening infringement procedures against any member that refused. The EC even started two infringement proceedings against Bulgaria: one citing TEP incompatibility and the other regarding the legality of pipeline's procurement process. Construction in Bulgaria stopped in August 2014.2

The conflict between Russia and Ukraine further impeded any possibility of South Stream advancing. EU-Russia energy relations further deteriorated and the South Stream working group disbanded. As consensus regarding building the pipeline crumbled, its $40-45 billion price tag began to weigh even heavier.3 4

But Gazprom continued to work on South Stream. The pipelay vessels arrived. Construction of the Russkaya compressor station was almost complete. Pipe for the offshore segment of South Stream's Line 1 (design envisioned four parallel pipes) was staged on the dock at Varna, Bulgaria, and pipe for Line 2 had been ordered.2

Gazprom spent $4.7 billion on the offshore and European sections before cancelling the project, divided roughly equally between offshore pipe and pipelay charter and pipe and compressors for the onshore Russian southern corridor (Fig. 2). Total outlay was roughly 40% of the $20 billion of capital investment required for the first two lines, designed to carry about 30 bcm/year.2

Industry analysts estimate Turkish Stream will cost Gazprom about $10 billion,3 a figure Russia's economy could manage despite its sharp slowdown. It will also be free of potential conflict with the TEP.

Russian exports, costs

Russia no longer wants to sell its gas directly to European end users, proposing a new gas hub at the Greek-Turkish border instead. Its refusal to agree to use only 50% of OPAL also shows an effort to shift away from an export policy anchored to fixed European customers. Trade now instead occurs as a purely commercial transaction, without attached economic or political commitments. Gazprom also recognizes that it will not be investing in Europe's mid or downstream natural gas infrastructure, both of which it had previously planned to do.2 Turkish Stream is an offshoot of these factors.

The switch from South Stream to Turkish Stream maximized Russian cost savings. Once the subsea pipe sections had been laid, Russia would have had little choice but to accept Bulgarian and EU decisions if it still hoped to monetize its investment.2 South Stream's estimated $40-billion total cost (for the full 63-bcm/year system) consisted of $17 billion for the Russian southern corridor, $14 billion for the pipeline's offshore section, and $9.5 billion for onshore European construction.2

By switching when it did, Gazprom limited its sunk expenditures primarily to work inside Russia. Estimates regarding how much this is range from 487.5 billion rubles ($9.4 billion) to €4 billion ($4.3 billion), the smaller coming from Miller who also maintains all of it will be applicable to Turkish Stream.5 6

Russia also anticipates having little problem finding demand for Turkish Stream's 30 bcm/year Phase 1 capacity, much of it within Turkey itself at better prices than it could get in Europe. Russia estimates 16 bcm/year of demand in Turkey beyond the 27 bcm/year it already imports and 3 bcm/year expected to be supplied by a Blue Stream pipeline expansion.

It expects to receive a price of $425/thousand cu m (Mcm) in Turkey compared with its $366/Mcm average in Germany the previous year.7 Estimates place Turkish imports of Russian gas at 40 bcm/year by 2020, out of total demand by then of 70 bcm/year.8 Turkey is already the second largest importer of Russian gas after Germany.

Turkish Stream will be ready more quickly than South Stream would have been. Russia is already building its Unified Gas Supply System (UGSS) expansion, including construction of the Southern Corridor gas pipeline system, crossing eight Russian regions with its western and eastern routes. Gazprom has also established a standalone company to build Turkish Stream9 and arranged to keep both pipelay vessels it had hired for South Stream on standby.3

Despite its near and medium-term demand, however, Turkey cannot substitute for the EU as a customer over the long run. Turkey will be able to absorb the bulk of Turkish Stream's first two lines (out of four), but future customers haven't been determined beyond the EU in general.

Gazprom generates 80% of its revenues by meeting one-third of Europe's current demand,10 and the EU will remain its most important consumer. But the relative lack of pipeline infrastructure in Southeast Europe makes it more difficult to deliver gas from Greece or southern Bulgaria, than would have been the case from Varna. While Gazprom hopes the EU will help its southern countries bridge this gap, failure to do so might sharply reduce Turkish Stream's overall viability.

Pros, cons

Turkey last year imported around 45 bcm of gas, 58% of it from Russia via the Blue Stream and trans-Balkan pipelines. Russian supplies were followed by Iran with 19%, Azerbaijan and Algeria with 9% each, and Nigeria with 3%. Spot acquisitions met the remaining 2% of its need.8

Turkish Stream would raise Russia's portion of this supply to roughly 70% but would also enhance Turkey's role as a supply hub, potentially increasing its leverage in membership talks with the EU and deepening the price discounts Russia might be willing to grant. These benefits would also be relatively cheap, Gazprom assuming offshore construction costs while offering Turkish companies an opportunity to participate in onshore construction, though potential shareholders remain unknown.19

In its ideal scenario, Turkey would become not only a transit country for gas on the way to EU, but also a gas seller through a hub on its border with Greece. This will only be possible after the planned liberalization of Turkey's gas market. It must also build necessary infrastructure to store and transport hydrocarbons. Turkey has limited gas storage capacity now and the launch of a gas stock exchange is still being discussed.8

It also is unclear whether Russia will allow Turkey to resell its gas, with no agreements in place for this. Regarding discounts, during his visit to Ankara Pres. Putin mentioned the possibility of a 6% discount now with deeper cuts possible in the future.14 With oil prices falling sharply in recent months, however, Turkey is looking for a discount of around 15%.11

Fears of increased dependence on Russian supplies may grow further if Gazprom acquires trading company Akfel Gaz, which in 2012 received a license to purchase 2.25 bcm/year of Russian gas. That same year, Akfel Gaz joined with State Oil Co. of Azerbaijan Republic (SOCAR) to form Gaz Ticareti AS; it can sell 800 million cu m/year out of the 1.2 bcm/year delivered to it by Petkim.

Gazprom already owns 71% of the other Turkish gas importer, Bosphorus Gaz, which has a contract to deliver 1.75 bcm/year. Gazprom also owns 1 bcm/year contracts with Kibar Enerji and Eksim Holding. The additional deal it's pursuing would make Gazprom Turkey's second largest retail natural gas supplier after Botas, establishing the security guarantees for its volumes denied in the EU.

Without South Stream, however, Russia's dependence on Turkey will also grow. Despite political disagreements between Russia and Turkey on issues such as the annexation of Crimea and the situation in Syria, economic relations between the two countries are growing rapidly, with Turkey emerging as an increasingly reliable customer for Russian gas.

EU position

The EU doubts there is sufficient demand in southeastern Europe to justify building Turkish Stream. Even if Gazprom has sufficient financing to build the first two lines, the EU sees little point in delivering an additional 30 bcm/year of gas to a region where, even by 2030, no individual country is projected to have demand exceeding 5 bcm/year.12 The 2013 demand for gas in Bulgaria, Serbia, and Greece combined was only about 9 bcm. EC vice-president for Energy Union, Maros Sefcovic, said a 63 bcm/year exceeds demand.14

At the same time, however, the EU supports the Trans Anatolian Pipeline (TANAP) and Trans Adriatic Pipeline (TAP). The joint projects will supply 16 bcm/year in Phase 1 and 31 bcm/year in Phase 2, less than half Turkish Stream's capacity, and included by the commissioner in weighing Turkish Stream.

Russia's gas-supply contract with Ukraine expires in 2019, introducing the possibility that Western Europe will need to find an alternate source for its supplies after that point. Western Europe last year imported roughly 140 bcm of gas from Russia and Eastern Europe only 40 bcm.12 South Stream was to have supplied Western Europe, and Turkish Stream might ultimately do the same given sufficient infrastructure, including regional improvements to the Trans-European Energy Network.

But when the EU rejected South Stream-or at least tried to prevent it from being built-it also lost the chance to access gas through a network that Russia was going to develop. By contrast, the EU will have to finance improvements to the poorly connected gas network in Southeast Europe. The EU has proposed the financing to do so but not at a level capable of delivering 30 bcm/year further west.

The EU Commissioner for Energy and Climate Action describes Europe's southern gas corridor as its top priority in efforts to diversify routes and sources of natural gas supply, and Hungary supports Turkish Stream despite EU hesitance. Bulgaria and Greece will also have a role to play in the project's success, and their position remains uncertain. Greece, for instance, has expressed its full support for TAP and its readiness to begin construction,13 but is also seeking more compensation than had initially been agreed.

Azerbaijan

Azerbaijan's government, secure in the knowledge that both TANAP and TAP will proceed, has not reacted negatively to Russia's Turkish Stream proposal. Both Turkey and Azerbaijan, in fact, intend to create an energy council encompassing 18 countries, including Russia, even while their energy relations are in supposed deterioration.

Others doubt Azerbaijan should be so sanguine, noting that while TAP's full 16 bcm/year is sold for the next 25 years, these arrangements may not be permanent.14 And when the first gas from Azerbaijan reaches the Turkish market, it could well already be receiving about 40 bcm/year of Russian gas, the first two lines of Turkish Stream expected to be operational by December 2016. Gazprom can secure additional advantages if it manages to build a gas hub for Turkey at the Greek border.

Azerbaijan in the meantime continues close energy cooperation with the EU. In a recent visit to Munich, Azerbaijan Pres. Ilham Aliyev declared the need for coordination with and support from European organizations if TAP is to avoid becoming bogged down in red tape, calling for a special approach to the project.15

Next steps

Gas could still move northwest through Bulgaria to the Baumgarten gas hub in Austria. This was to have been the destination for gas transported by South Stream but would require an entry point a few hundred kilometers farther south for use with Turkish Stream, perhaps re-energizing Nabucco-West.16

Joint use of TANAP or TAP by the Shah Deniz II consortium and Russia is another possibility. According to Russian experts, if both TANAP and Turkish Stream deliver gas, it would be in TAP ownership's interest to allow Russian gas-also arriving at the Turkish-Greek border, at likely lower prices than Azeri gas-into its pipeline.17 Azerbaijan and Russia have a precedent in crude transportation for this kind of cooperation, Azeri light crude being exported with Russian crude via Baku-Novorossiysk and sold at a higher price because of the lower quality of the Russian oil.

Russia may propose a similar framework for exporting natural gas and TAP's operators might be interested simply for the added speed with which it would allow them to recover their costs. Azerbaijan's stance is more complicated. While the additional Russian gas would increase the southern gas corridor's efficiency and diminish network costs, it would also threaten Azerbaijan's market share. Even so, Azerbaijan would probably have to be more flexible in its pricing than without Russian competition, lower transport costs helping the bottom line.17

Such an arrangement would make strategic sense for Gazprom, allowing it largely to control a new gate for gas deliveries into Europe's south and southeast. Russian gas would then not only bypass Ukraine, but also spoil the rationale of one of EU's main diversification projects. The new Russian pipeline would join a transport system already aligned with the TEP standards on EU territory, an outcome similar to what South Stream would have achieved had it agreed to follow TEP rules in the first place.17

Russia's position, however, that Gazprom could use TANAP to transport Russian gas to Europe, given its 30 bcm/year capacity and 15 bcm/year of Azeri supply, is tenuous. By the early 2020s Azerbaijan is to export an additional 15-16 bcm/year, but by 2025 according to SOCAR's projections, Azerbaijan will be able to produce about 30 bcm/year more. Ten years from now, therefore, and 6 years after TANAP's inauguration, Azerbaijan will be able to fill the pipeline with its own production (Shah Deniz II and Absheron).

According to Turkey's Energy Minister Taner Yildiz, Russia and Turkey are also considering building an LNG terminal on the Greek border.18 The project lacks details but would be intended to export Russian gas to Europe without having to deal with EU pipeline regulations. It also coincides with Russia's unwillingness to deliver directly to end users.

Routing

Russia and Turkey are negotiating regarding the two most likely delivery points for the pipeline: Samsun or Istanbul. Yildiz said that Turkey prefers the Frakia region of Istanbul because Samsun already has Blue Stream and the European part of Turkey consumes a lot of gas, currently supplied through the Trans-Balkan Gas Pipeline.19 Russia, however, prefers the new pipeline to parallel Blue Stream, with a similar landfall at Samsun.

Route choice may greatly affect project timing. The preferred Russian option could avoid significant new undersea surveying to the degree it parallels Blue Stream to Samsun but would require substantial additional onshore capacity to take the gas westwards to join the Trans-Balkan line, which supplies Gazprom's customers in Southeast Europe and Turkey.

The preferred Turkish route, by contrast, would allow two parallel lines to follow the previously proposed South Stream route (also already surveyed) before diverting away from the Bulgarian economic zone and going directly to the Turkish mainland and connect with the Trans-Balkan pipeline just south of the Bulgarian border.2

Routing is the last obstacle to construction. Technical issues are mainly solved. Lay barges remain on station in Varna, Bulgaria.

Volumes

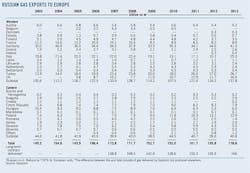

The target market for the Turkish Stream has yet to be determined, but Southeast European demand for Russian gas remains limited. Bulgaria, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Greece, Macedonia, Romania, Serbia, Slovenia, and Croatia imported less than 10 bcm of Russian gas in 2013, and even adding Hungary and Austria only brings the total to 21 bcm.2 Interconnections are also sparse in the region.

The EU's European Energy Program for Recovery, however, has prompted construction of Hungary-Croatia, Romania-Hungary, Poland-Czech Republic, and Bulgaria-Romania interconnectors. The Interconnector Greece-Bulgaria (IGB) is going to be commissioned soon and is expected to be a major route of delivery for Russian gas to central Europe. These interconnectors would allow Russia to pump its gas to the Southeast European clients at relatively low costs but would also still leave final approval of Russian gas deliveries with the EU.

Some European countries along South Stream's planned route-including Bulgaria, Hungary, and Serbia-initially welcomed the Turkish Stream proposal as a source of transit fees and an alternative source of gas.3 Media reports from Greece citing sources from the Energy Ministry indicate Athens will seek a stake for Greece in TAP, annual transit fees, and a reduction in the cost of natural gas imported from Azerbaijan. Russia has so far been receptive to Greece's interest.20

Turkish Stream would free Gazprom of dealing with Europe regarding pipeline construction. Russia could still bring gas to European markets, while saving the money it would have spent on building pipelines there. It also reaches Europe without crossing Ukraine.21

Another point of debate is whether Gazprom will be able to raise sufficient finances simultaneously to support building:

• Four parallel offshore pipelines (Turkish Stream).

• The Power of Siberia pipeline for which it signed a 38 bcm/year contract with China National Petroleum Corp. for deliveries starting 2018.

• The $18.5-billion Altai pipeline from Western Siberia to the Chinese border (pending a 30 bcm/year contract to be signed this year with deliveries starting in 2020).2

Turkey will not be involved in building Turkish Stream's offshore section but could be a partner of the onshore section of the gas pipeline.

References

1. BP Energy Outlook 2035.

2. Stern, J., Pirani, S., and Yafimava, K., "Does the cancellation of South Stream signal a fundamental reorientation of Russian gas export policy?" Oxford Energy Comment, January 2015.

3. Reed, S., and Arsu, S., "Russia Presses Ahead With Plan for Gas Pipeline to Turkey," New York Times, Jan. 21, 2015.

4. Panin, A., "Russia's New Turkish Stream Gas Strategy More Bark Than Bite," Moscow Times, Jan. 21, 2015.

5. Bierman, S., Arkhipov, I., and Mazneva, E., "Putin Scraps South Stream Gas Pipeline After EU Pressure," Bloomberg, Dec. 2, 2014.

6. "Miller about change of Russia's strategy at Europe's gas market," caspianbarrel.org, Dec. 7, 2014.

7. "Putin: Russia Cannot Continue South Stream Construction in Current Situation," Sputnik News, Dec. 1, 2014.

8. Kömürcüler, G., "Could Turkey become more dependent on Russian energy?" Hurriyet Daily News, Dec. 10, 2014.

9. "Russia creates company for construction of gas pipeline to Turkey," caspianbarrel.org, Dec. 10, 2014.

10. Gloystein, H., and Zhdannikov, D., "Russia's South Stream pipeline falls victim to Ukraine crisis, energy route," Reuters, Dec. 2, 2014.

11. Jones, D., "Russia & Turkey: Putin Makes a Pipeline Play, but Will It Pay?" EurasiaNet.org, Dec. 9, 2014.

12. Dickel, R., Hassanzadeh, E., Henderson, J., Honoré, A., El Katiri, L., Pirani, S., Rogers, H., Stern, J., and Yafimava, K., "Reducing European Dependence on Russian Gas: distinguishing natural gas security from geopolitics," Oxford Energy, October 2014.

13. "Lafazanis: "The Greek government fully supports the TAP pipeline," Tovima, Feb. 13, 2015.

14. Beckman, K., "In the new energy security war, Europe has the upper hand over Russia, say top US officials," Energy Post, Nov. 28, 2014.

15. "Ilham Aliyev talka about energy security in Munich," Vestnik Kavkaza, Feb. 9, 2015.

16. Gurkov, A., "Opinion: The pipeline is dead! Long live the pipeline!" Deutsche Welle, Dec. 2, 2014.

17. "South Stream's Cancellation: The End of a Saga," Natural Gas Europe, Dec. 10, 2014.

18. "First branch of new gas pipeline to Turkey could be built in 2-3 years," Turan Informasiya Agentlivi, Dec. 12, 2014.

19. "Turkey offers Gasprom longer route: struggle for interests starts," Turan Informasiya Agentlivi, Dec. 12, 2014.

20. "Ilham Shaban, Southern Gas Corridor Advisory Council Meets; Fears and Hopes," Natural Gas Europe, Feb. 14, 2015.

21. Mihalache, A., "South Stream Is Dead. Long Live South Stream," Energy Post, Jan. 12, 2015.

The author