George Baker

Baker & Associates Energy Consultants

Houston

The Mexican energy reform of 2014 encompasses all links in the oil, gas, and power value chains. The roll-out of new agencies and the restructuring of old ones will take a decade. In the upstream, the Mexican government is 2 years out of sync with the oil market. Had the reform been launched when oil prices were $100/bbl, the level of interest in Houston by international oil companies (IOCs) and service companies could be hot (depending on the terms offered); but at $50/bbl, that interest is lukewarm. This article identifies positive and cautionary signs.

Why Mexico at $50/bbl?

For the past decade, the US onshore and the Outer Continental Shelf have been the global sweet spots. How can Mexico, with an untested fiscal and regulatory regime, and haunted by unchained cartel violence onshore, compete for IOC capital when oil is at $50/bbl?

One answer is that the Mexican portion of the Gulf of Mexico is said to be the largest unexplored petroleum provinces on the planet, second only to the Arctic Circle. In terms of prospective shale gas resources, there have been estimates of 400-650 tcf. Subsalt plays have yet to be identified.

A second answer is that for a half century, IOCs have been waiting for an opportunity to do business in Mexico on internationally acceptable terms. The 2014 oil reform is an initial step toward offering such terms.

The reform follows the upstream logic that geologist James L. Wilson Jr. and I proposed 20 years ago when we observed that instead of having Pemex as a one-size-fits-all oil company as the exclusive operator, Mexico would be better served by matching distinct basins and plays with many operators of appropriate market caps and skillsets.1

Origins of reform

Mexico's energy reform began in earnest on Dec. 20, 2013, when the constitutional changes brought about under Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) leadership came into effect. As important as were the textual changes, it was the 20 transitional articles that put meat on the table.

Neither the date nor goal of the original discussion that led to the spudding of this market redesign is known to the public. There are grounds for believing that, on the oil side, the design was largely completed by the end of the two successive National Action Party (PAN) administrations; while, on the electric-power side, the design went back to the late 1990s during a PRI regime. Not for nothing did waves of Mexican government officials during those 15 years travel to Norway, Brazil, Canada, and the US (among other jurisdictions) in search for ideas about regulatory and institutional design.

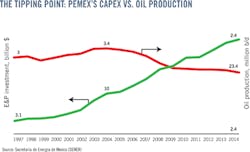

The tipping point that forced the government to modify its upstream regime came when the divergent trend lines of Pemex's capital budget and trend lines were compared. In a single decade, when Pemex's budget had more than doubled while it had lost 1 million b/d of oil production (Fig. 1).2 "Enough!" was the collective sigh of the president and his advisors inside and outside of government.

On Aug. 11, 2014, more than a dozen pieces of new and amended legislation were promulgated in a grand, presidential ceremony, thus giving in legal shape to what came after that collective sigh.

To market the new petroleum regime, throughout 2014 (and continuing in 2015), there have been an uncounted number of seminars on Mexico's energy reform, including an official roadshow held Oct. 20, 2014, in Houston, funded by the University of Texas at Austin's Jackson School of Geoscience.

Sobriety's starting point

The starting point for sobriety about Mexico's energy reform is found in the meaning of reformar, which in Spanish means "to amend," as of a text, not to reform, as of policy. Where, in Venezuela in the 1990s the term apertura was used-without any caviling-to mean "opening," in Mexico, reformar admits of multiple shades of gray.

Therefore, looking at Mexico's energy reform from these two sides, one can see there are both smooth and rough edges with which to contend.

Smooth edges

In the discussion in early 2013 that led to the redesign of the upstream, a consensus was reached that the restrictions of the Petroleum Law of 1958 were now obstacles to the development of the nation's petroleum resources: By forcing all capital investment and technology through a funnel of Pemex contracting, the state lost flexibility with which to respond to new geological plays and technologies. So the first order of business was to regain that flexibility, a process that, in the course of things, would abrogate the cited dysfunctional (and unconstitutional3) law. New plays were shale and deepwater oil and gas and heavy oil.

At some point in this discussion, a consensus was reached that Pemex, on its own, would never catch up with developments in shale plays in the US onshore and in deep and ultra-deepwater plays on the OCS. Oil production, meanwhile, was continuing to fall, and with a third of government revenue dependent on the oil sector, the deteriorating situation demanded leadership for change.

With the guidance of lawyers from Curtis Mallet, the shards of regulatory and institutional insight collected from around the globe came together in a unique Mexican design: for the upstream, there would be a bicameral regulatory architecture, as in the US, Norway, and other countries, where one agency would be responsible for leases and a second for safety and environmental enforcement. In the Mexican design, the first role would fall to the National Hydrocarbon Commission (CNH), and the second role to a Petroleum Safety Agency (ASEA).

For the power sector, the dispatching unit that had been ensconced in the Federal Power Utility (CFE) would be brought out into the light of day as an independent system operator (CENACE). Midstream gas would finally see the spin-off of the pipeline division of Pemex Gas (PGPB), plus the unexpected creation of a Transportation System Operator (CENAGAS).

The pentagonal table of public policy and oversight of the energy sector would have five seats, corresponding (in addition to those mentioned) to the Ministries of Energy (SENER) and Finance (SHCP) and a restructured midstream and downstream regulator (CRE). The Finance Ministry would sit at the head of this table.

As for leasing exploration acreage, the ideas for a Round Zero and Round One were imported from Brazil. At first, Pemex would be allotted acreage in producing and prospective blocks; later, other blocks would be opened for general bidding.

The novelty of the Mexican upstream strategy lay in a calculation that a market design that would have farmout as its central feature would satisfy both those constituencies in Mexico who want to keep a framework focused around Pemex as well as those who want to see new faces. A large-scale farmout program would do both. Pemex would be allotted vast tracts of unexplored and undeveloped acreage (as in Perdido) where new faces in farm-in relationships with Pemex would be encouraged. Existing farmout contracts (known by several acronyms) would be subject to novation in order to conform to the new options for a contract model: license, production-sharing, and profit-sharing.

With these elements in place, the government could sit back and wait for the synergy of the new farm-in relationships to do its magic in three dimensions: stimulate capital inflows, increase the rates of exploratory drilling and production, and prepare Pemex to compete-in collaboration with its farm-in partners-as a bidder for blocks that will be open to the general upstream public.

As the synergy worked, so also would the Mexican peso strengthen in value, and global investors would seek sectors that are economically contiguous to the energy sector (e.g., auto, petrochemical). Mexico's commercial aura would progressively gain in luminosity.

Rough edges

There also are rough edges in this market design. Some of these will be smoothed out naturally, as when the model contract is revised after stakeholder input. Petroleum fiscal analyst Pedro van Meurs, who has been an advisor both to Pemex and SENER, strongly believes that with focused public comment by prospective bidders, authorities in Mexico will respond by moving the terms of reference into better alignment with international expectations.4

Other rough edges will be more difficult to smooth over, at least in the short term. To begin with, the language of the new statutes is abrasive in places: a lease-holder is termed a contratista, not licenciatario, which was the PAN-era neologism that is euphonious with "licensee" and that appears in the 2012 US-Mexico Transboundary Hydrocarbon Agreement. What is globally understood to be an oil field "service contractor" in Mexico is awkwardly referred to as "a third party."

The government's business model that has been presented in roadshows in the US and Europe is not one that embraces market solutions. The state-centric design of the model is not immediately apparent, however, even to the experienced eye.

For choosing not to update Mexico's traditional, globalphobic, petroleum narrative, the government finds itself in the awkward position of having to bend global concepts and definitions to fit in with the political expectations of domestic audiences. Thus, the Hydrocarbon Law states that the volumes in the subsurface that are economically recoverable (including those in undiscovered resources) are the property of the "Nation."

Pausing, you realize that there is a deep misunderstanding in the room. Oil reserves are mental events that produce computer-generated estimates of recoverable volumes, given current technology and market conditions. They can be in the subsurface only in relation to other papers on a geologist's desk.

In Mexico, only the state is to report reserves in physical units. The licensee is authorized to report only the "expected economic benefits" related to his lease area. Such an arrangement may work for the very large and the niche player (such as Shell and Petrofac), but it will be awkward, if not impossible, for everyone else.

A nearby rough spot is the ambiguity about the bidding variable. The Hydrocarbon Revenue Act gushes about "maximizing" oil rent, thus giving the impression-a false one, according to van Meurs-that an award will be mechanically made on the basis of the highest government take. Such an arrangement would do nicely to protect public officials of any future accusation of favoritism, but it would serve the nation poorly.

Another edge that needs smoothing concerns penalties and sanctions. The law reads that a contract may be rescinded as a result of a serious safety incident. It is one thing to suspend, or even revoke, a lease-holder's permit to operate in a block for a pattern of egregious violations of substantive terms; it is an entirely different matter to rescind his license on account of a single event that is deemed to be serious. From the operator's perspective, it would be to expropriate his investments that had led to commercial discoveries. It would be to reduce the NPV associated with those discoveries to zero.

On balance

From this discussion, it should be easier to see that much of the new upstream regime in Mexico is still inside baseball. On balance, Mexico has made a slight, but meaningful, gesture toward alignment with industry expectations. Some of the rough edges will be smoothed out naturally; while others will require new political will on the part of authorities. In the meantime, the rough edges will entail additional layers of risk for the prospective bidder.

Footnotes

1. See "Mexico's basins could provide niches for various sized firms" (OGJ, Nov. 18, 1996, p. 53). Marathon Oil's Mark Bitter also contributed to this article.

2. For Fig. 1 and related slides of the Feb. 6, 2015, webinar of Hydrocarbons Secretary Lourdes Melgar, see www.iamericas.org/en/events/past-events.

3. The law was abrogated in the 2014 legislation. There was no constitutional basis for its Article 6 (which banned payment in kind); but a test by the Supreme Court was never made, as no parties had legal standing to do so. We know of only one case in which the Supreme Court intervened in the energy sector on a matter of law. In a test of consistency in the rulings of federal and local courts (Tésis 193/2011), the court ruled that local and state courts may not issue injunctions against activities that had been authorized by federal agencies (in a case that arose from the harassing injunctions of the local natural gas distributor in Guadalajara).

4. An extended interview with Pedro van Meurs is posted on www.energia.com.

COMMENT

The author