West Coast CBR-project legal risks require management

Gabriel Collins

Baker & Hostetler LLP

Houston

Matthew Lanahan

Arnold & Porter LLP

Washington

Alexander Obrecht

Baker & Hostetler LLP

Denver

Siting crude-by-rail (CBR) terminals in areas that already have high volatile organic compound (VOC) emissions is among the steps companies can take to reduce the risk of legal action against their construction and operation.

Opposition groups are honing their legal strategies for delaying CBR projects and are beginning to effectively apply these strategies to stop or delay projects in key markets such as California. InterState Oil Co., for example, was pressured into halting operations at its crude offloading terminal near Sacramento in November 2014 after the Sacramento Metropolitan Air Quality District said it had mistakenly sidestepped California environmental rules by issuing a permit without conducting a full environmental impact review.1

Similar legal hurdles confront CBR projects in other West Coast states. Skagit County (Wash.) Planning and Development Services in 2014 concluded that a proposed CBR offloading terminal at Shell's Puget Sound refinery did not require full environmental review under the Washington State Environmental Policy Act.2 But the county reversed course in the face of environmental protests and ruled that the terminal must undergo full environmental review. A Washington state judge in May 2015 affirmed the county's decision to undertake full environmental review.

Political opposition and oil price volatility, meanwhile, are likely to sharply reduce companies' ability and willingness to invest in pipelines, meaning California and the East Coast will remain heavily reliant on railborne and waterborne crude oil. Among major midstream operators the debate is increasingly not about pipe vs. rail, but rather how to best integrate the two delivery modes to maximize efficiency and optionality of crude supplies to end users.

CBR activity is likely to increase nationwide, particularly if there are no reforms made to the Jones Act to lower the costs of coastal shipping between US ports. Rail transport will remain crucial to the crude oil supply chain, creating business opportunities while also inflaming opposition. This article outlines the emerging legal and regulatory risks CBR projects face and outlines strategies to help industry better shield against them. Our analysis and suggestions are particularly tailored to California, Washington, and Oregon, which present large market opportunities for railborne crudes and are also among the jurisdictions with the highest levels of opposition to CBR project development.

CBR outlook

Despite a slowdown caused in part by low oil prices, two core factors will support continued use and growth of crude-by-rail in the US:

• Light sweet, mid-Continent crude oils will remain at a competitive disadvantage in the US Gulf Coast market due to strong production growth of local light sweet grades from the Eagle Ford and Permian, and widely available waterborne light sweet crudes from abroad.

• Canadian producers will continue to face severe political obstacles to building pipelines such as the Keystone XL, the Energy East project, or a pipeline through British Columbia to the Pacific Ocean.

Anti-oil sands and anti-emissions activism actually stand to drive more Canadian heavy sour onto the rails and toward the one marketplace where it is welcome: the US Gulf Coast. Canadian heavy sour barrels help Gulf Coast refiners balance plant operations in the face of light sweet supplies flooding in from domestic shale plays. The US Gulf Coast also offers opportunities for exporting Canadian crude to a variety of foreign markets, possibly even Asia, via the expanded Panama Canal.

Rising rail shipment of Canadian crude to the US Gulf Coast will substantially increase demand for railroad throughput. Moving oil from Central Alberta to key US demand centers can require 30% or more rail capacity than traditional Bakken crude movements from North Dakota because the longer transit distances require more cars to maintain a set level of crude deliveries. Rail shipments of Canadian crude to the Gulf Coast totalled 69,000 b/d as of June 2015, according to US Energy Information Administration (EIA) data. By 2018, regional rail terminals will likely be able to accommodate more than 400,000 b/d of diluted bitumen and bitumen unloaded with steam heating.

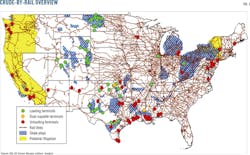

Continued delays of cross-border pipelines will support higher rail shipments and additional investments in terminal capacity on the Gulf Coast and likely in California as well. A terminal capable of unloading 140,000 b/d (two unit trains) costs about $150 million and can be built in 18-24 months.3 CBR is an attractive option for quickly and flexibly getting Canadian crude to US markets. But additional litigation is likely, particularly in California, Oregon, and Washington, states with the capacity to take additional railborne volumes, both for local use and, potentially, for export. Fig. 1 highlights potential litigation hotspots in yellow.

Legal vulnerabilities

Since the Lac-Megantic, Que., derailment (OGJ Online, July 8, 2013), environmental and community groups have intensified their opposition to CBR. This opposition increasingly has been finding its way into the courtroom.

Companies must first understand which federal or state agencies have jurisdiction over CBR projects. Where jurisdiction falls decides where an opponent may challenge a CBR project. Under the Federal Railroad Safety Act of 1970 and the Hazardous Materials Transportation Act, and other statutory schemes, Congress has preempted most state control over railroads and hazardous materials. In doing so, Congress established regulatory authority in these areas with the Federal Railroad Administration (FRA), the Pipelines and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA), and the Surface Transportation Board (STB).

State and local governments, however, generally have regulatory authority over land-use issues, state environmental laws, and federal environmental laws that grant states authority to implement federal programs. States and localities have effective control over zoning, environmental laws of purely state concern, and state implementation programs under the Clean Air and Clean Water Acts.

Companies must be wary of federal issues opposition groups may raise before state authorities. In October 2014, for example, environmental groups petitioned the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (NYSDEC), requesting a prohibition on the "receipt and storage of Bakken crude oil in DOT-111 tank cars" throughout the State of New York.4 The groups attempted to invoke NYSDEC's regulatory power over CBR transloading sites, essentially a land-use issue.4 But by seeking a blanket prohibition on crude oil receipt and storage in DOT-111s, the petition effectively asked the state to regulate tank cars allowed by federal regulations to transport crude oil.5

The environmental groups' petition requested that a state take action contrary to the federal supremacy over the regulation of railroads and hazardous materials. Because federal law preempts state regulation over railroads-specifically here as to the type of tank car that may be used to transport crude-states lack the power to decide otherwise. Even though the petition rested on untenable legal grounds and the NYS-DEC took no action on it, it demonstrated environmental groups' willingness to increasingly stretch the boundaries of states' regulatory powers to stop CBR projects.

CBR companies also must be wary of the considerable ammunition environmental groups have under state law. Many relevant state laws and permitting regimes-particularly in California-provide ample opportunities for opposition groups to cause companies, and state agencies, delay.

Our analysis focuses on California for two primary reasons. Based on low use of current capacity and the existence of several prospective high-volume CBR sites, the state has upside for boosting crude oil rail deliveries. California has about 1.5 times as much refinery capacity as the East Coast, which depends heavily on CBR. California's in-state crude oil production also has steadily declined and will likely continue falling even as the demand for refined fuels remains robust. These factors suggest that the California market has room for at least 350,000-400,000 b/d in additional CBR deliveries. Neighboring states will likely take cues from the decisions made by California's sophisticated-and frequently anti-industry-regulatory and judicial apparatus.

Table 2 highlights the potential pressure points for legal action at various stages of the CBR terminal permitting process in California.

The National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) and its state equivalents require environmental review for any government decision that will have a significant environmental impact. CBR projects can avoid the NEPA process if the government does not have to make a decision at all. Or the decision in question can be categorically excluded as having a significant environmental impact.

But if the proposed project is subject to NEPA, varying levels of review apply, corresponding to the significance of the environmental impact. The permitting agency first prepares an environmental assessment. If the agency concludes that there is no significant impact, it issues a finding of no significant impact. If a significant impact is found, the agency must prepare an environmental impact statement.

NEPA requires an informed decision-making process. But NEPA does not mandate an outcome, meaning that the government must gather all relevant information but the information does not dictate whether a project is approved. Faulty NEPA analysis, however, opens the door to environmental challenges and serious delays to CBR projects.

Environmental groups' concerted effort in early 2014 against CBR projects began with challenges under California's NEPA equivalent, the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA). The first suit challenged the Bay Area Air Quality Management District's decision to forgo CEQA analysis in permitting a site Kinder Morgan wished to retrofit as a CBR terminal. A San Francisco Superior Court judge dismissed the lawsuit, however, on timeliness grounds.6

Environmental groups have continued challenging CBR project permits classified as "ministerial" that avoided CEQA review. The movement has gained momentum. Shortly after losing in San Francisco County, environmental groups filed another lawsuit in Sacramento County, accusing a local agency of illegally permitting a CBR transloading terminal.

The lawsuit targeted a permit issued to InterState Oil by the Sacramento Metropolitan Air Quality Management District to transfer crude oil from trains to trucks.7 The environmental groups alleged in the suit that the district illegally authorized the permit without the requisite public notice and comment in violation of CEQA. The groups asked the court to revoke the permit and declare that the district violated CEQA. Without waiting for the court's ruling, the district admitted that it erroneously issued the permit without the requisite "full CEQA review."1 InterState Oil voluntarily returned the permit and stopped using the site for CBR transloading.8

California lawsuits will likely accompany each proposed new or repurposed transloading site (Table 2).8 One pending suit in Kern County, however, goes past merely requiring CEQA review for CBR projects, and requests the invalidation of the Kern County Board of Supervisor's environmental impact review (EIR)-the highest state level of environmental review-for the project. The lawsuit targets the Alon Bakersfield refinery flexibility project, which seeks to revamp and restart the refinery by increasing CBR capacity from 40 to 200 tank cars/day. The Alon refinery, however, has not refined crude oil since 2008.

The lawsuit attempts to invalidate the EIR by obfuscating the baseline for environmental analysis. The environmental groups asked the court to base it on current shut-down conditions, not the conditions that existed when the refinery was operating and properly permitted in 2007. This lawsuit signals environmental groups' willingness to challenge not only the procedural requirements of CEQA but the substance of the CEQA review as well.

Practical strategies

Lawsuits to stall proposed CBR terminals in California often allege that local air quality boards' decisions bypassed the EIR process in issuing operating permits.9 If approached correctly, however, the EIR process presents a significant opportunity to both frame and potentially forestall lawsuits. The EIR process can form the central part of a holistic strategy focusing on community relations and transparency to address general political opposition, which, if left unaddressed, is likely to fuel legal challenges. EIRs are meant to address significant environmental impacts, ways they can be mitigated, and alternative courses of action.10 They are also meant to provide information to guide future decisions.11

Once courts begin ruling on CBR terminal siting and operations cases, the precedents set could embolden CBR opponents and prompt further challenges. Effective use of the EIR process, however, can instead build a foundation that will both avoid litigation and provide stepping stones for future projects.

Currently, the strongest opposition to CBR development lies in major metropolitan areas along the California coast. Kinder Morgan has already picked the low-hanging fruit with its Richmond terminal, repurposed from handling railborne ethanol shipments. Anti-CBR officials and private groups will fight future CBR projects in these areas, as Valero discovered via multiple delays to its proposed CBR terminal at the Benecia refinery.

Proposals for new CBR terminals and operational expansions at existing sites will almost certainly spark lawsuits. The best legal strategy is to defang the plaintiffs. Three concrete actions can seriously weaken the majority of terminal-specific claims:

• Terminal builders should immediately launch an EIR, as this preempts attacks based on improper issuance of air permits. As shown by the InterState Oil Sacramento case in November 2014, legal attacks based on air quality boards' ministerial issuance of a permit without an EIR are sufficient to cause agencies to withdraw their approvals.

It is better to preempt injunction suits by conducting an EIR upfront, since courts are increasingly likely to force review anyway. Avoiding the EIR fight also reduces the risk of future operational disruptions and streamlines the litigation process by many months. This in turn helps accelerate terminal permitting and will likely help get CBR terminals online more quickly than would trying to initially obtain an air permit without an EIR.

Engaging the EIR process head-on while planning CBR projects also allows industry to frame the conversation. Over time, greater information transparency by terminal operators will help improve the industry's public perception and the public's trust by giving terminal neighbors, voters, and policymakers an alternative-and more accurate-perspective.

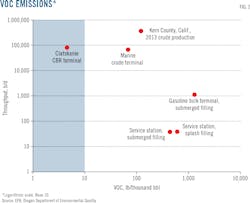

It sounds ominous, for example, that a unit-train class CBR terminal such as Global Partners' in Clatskanie, Ore., can emit approximately 70 tons/year of volatile organic compounds (VOC).12 But according to US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) data, this is the same amount of VOC emitted by just 25 gasoline service stations.13

This is just one example of how facts can be used to inform an EIR report. An EIR must include basic required elements, but the format allows substantial freedom in how they are addressed, allowing industry to highlight the true nature of the project and to place it in an accurate context. Relative to other crude oil and refined product infrastructure, CBR terminals are high-throughput, low-VOC emissions sites (Fig. 2).

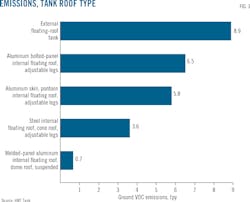

• CBR developers should also use cost-effective steps to reduce VOC emissions and incorporate these into project plans reviewed during the EIR process. Installing geodesic domes on the terminal's storage tanks, for instance, and building overhead cover for car unloading racks to reduce solar heating can significantly reduce VOC emissions. Industry data suggests these reductions can be as large as 80-90% for volatile, high vapor-pressure crudes stored in floating-roof tanks,14 slashing the project's overall VOC emissions rate.15

Changing the design of a 120-ft diameter tank capable of storing 88,600 bbl of gasoline can reduce VOC emissions by more than 90% (Fig. 3). This calculation is for storage of gasoline with a 10 psi Reid vapor pressure (RVP), which closely approximates the volatility of Bakken crude oil. It is more expensive to install restrictive roofing, but the decision makes financial sense over time because operational disruptions caused by emission-related litigation can cost more than $100,000/day in lost revenues for a unit train-class terminal. The same logic applies to installing overhead shade cover for tank car unloading racks.

• Developers should stabilize Bakken crude slated for rail shipment to the West Coast, particularly in California, where extremely tight VOC-emissions standards would otherwise risk unduly constraining the volumes a terminal can receive. Because the lightest ends of the barrel are among the lowest in value for crudes entering complex refineries in California, stabilization should not materially affect the netbacks producers get for their crude.

Stabilizers for field crude typically cost $0.50-$1.00/bbl.16 Producers could tolerate these costs even at today's prices if the procedure significantly increased their ability to access more of the large, and still relatively untapped, West Coast and California refining markets.

Stabilization would also create surplus NGL in the Bakken area. The challenges of dealing with a new NGL stream in the area illustrate that stabilization of Bakken crude is a least-worst option for making CBR terminals viable in the west-coast Petroleum Administration for Defense District (PADD) 5 regulatory environment. Ongoing infrastructure improvements for moving NGLs to external markets, however, could help accommodate greater use of stabilization. For instance, Oneok Partners finished expanding its Bakken NGL Pipeline in October 2014, adding 75,000 b/d of outbound capacity and bringing the line's total potential throughput to 135,000 b/d.17

Assuming a 5% light-ends removal rate/bbl, stabilizing each 110-car unit train (70,000 bbl) bound for PADD 5 refineries would create 3,500 bbl of NGL, roughly 5 railcars' worth.

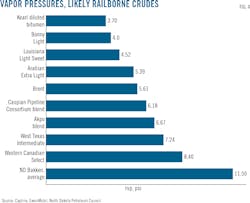

Stabilization could also allow existing terminals to ramp up throughput while remaining within their permitted emissions limits. A crude oil's vapor pressure often correlates strongly with its VOC emissions.18 If Bakken crude can be stabilized from its typical 11.5 psi vapor pressure down to West Texas Intermediate's 7.24 psi (Fig. 4), this could, in theory, allow a CBR terminal to increase throughput without exceeding its permitted VOC emissions threshold. Determining the exact throughput increase would require a detailed chemical and engineering calculation, but it could exceed 20%.

Reducing VOC emissions of inbound crudes could expedite the process of amending terminals' operating permits to increase throughput. Developers could plausibly argue that using less volatile crudes to increase terminal throughput while keeping VOC emissions within previously permitted parameters was ministerial and would not require new environmental impact reviews. A ministerial action involves little or no judgment by the public official regarding "the wisdom or manner of carrying out the project." A discretionary project, by contrast, requires officials to use "judgment or deliberation" as they consider whether to issue a permit.

High-VOC sites' solution

Sites with high recent historical VOC emissions are strong candidates for CBR terminal siting because CBR operations emit relatively little VOC per barrel of throughput. Such sites come with a high baseline for determining emissions thresholds. This concept succeeds in legal terms because the fundamental goal of the EIR process is to "inform decision makers and the public of any significant adverse effects a project is likely to have on the physical environment."19 To do this, the EIR must define a baseline against which the project's anticipated effects can be described and quantified.19 This requirement and the California judicial decisions addressing it potentially offer a unique solution for CBR operators regarding siting projects near idle oil refineries and declining oilfields

Terminal opponents claim that the EIR process for a CBR terminal proposed at the site should use the refinery's "currently non-operational conditions as the baseline for measuring impacts."20 If this approach were followed, the CBR terminal would likely not be able to receive an operating permit due to tight emissions restrictions driven by existing ozone and particulate pollution problems in the San Joaquin Valley. But opposition groups' legal position on what constitutes a proper EIR baseline is likely incorrect.

A number of California courts clearly state that a property's recent historical use can provide a "realistic measure of existing conditions" for the purposes of an EIR impact assessment."19 Their position remains true even when the historical use occurred many years earlier or was intermittent. California courts make liberal time allowances for historical use analysis of mining and natural resource projects because they recognize that such endeavors are subject to macro-level fluctuations in supply, demand, and price that are unpredictable and beyond project operators' control.21 Alon USA's 70,000-b/d Bakersfield refinery-mothballed due to global oil price swings and declining local crude supplies-is a prime example of a site that under this caselaw could accommodate much larger crude-by-rail deliveries.

References

1. Bizjack, T. and Tate, C., "Sacramento crude oil transfers halted; air quality official says permit was granted in error," Sacramento Bee, Oct. 22, 2014.

2. Skagit County Planning & Development Services, "SEPA Staff Findings No. 6," Apr. 22, 2014.

3. George-Cosh, D., "Enbridge Plans US Rail Loading Facility for Crude," Wall Street Journal, Aug. 1, 2014.

4. Earthjustice, "Petition for Summary Abatement Order: Receipt and Storage of Bakken Crude Oil in DOT-111 Tank Cars at Albany Terminals Operated by Global Companies LLC," Oct. 20, 2014.

5. Federal Register, "Hazardous Materials: Enhanced Tank Car Standards and Operational Controls for High-Hazard Flammable Trains," Aug. 1, 2014.

6. Carroll, R. and Chaussee, J., "California Judge Throws Out Lawsuit Targeting Crude by Rail Facility," Reuters, Sept. 5, 2014.

7. California Superior Court, No. 34-2014-80001945, "Verified First Amended Petition for Writ of Mandate and Complaint for Declaratory and Injunctive Relief: Sierra Club v. Sacramento Metropolitan Air Quality Management District," Sept. 23, 2014.

8. Mulkern, A.C., "California: Lawsuit Filed to Block Expansion of Crude-by-Rail Terminal," E&E Publishing, Jan. 30, 2015.

9. California Superior Court, "Verified Petition for Writ of Mandate: Communities for a Better Environment, Sierra Club, ForestEthics, Center for Biological Diversity, and Association of Irritated Residents v. San Joaquin Valley Air Pollution Control District (Bakersfield Crude Terminal LLC, Plains Marketing LP, Plains LPG Services LP, and Plains All American Pipeline LP), Jan. 28, 2015.

10. California Public Resources Code § 21002.1(a), 1996.

11. California Public Resources Code § 21003(d), 1996.

12. Oregon Department of Environmental Quality, Northwest Region, "Response to Comments - Proposed Air Contaminant Discharge Permit (05-0023-ST-01) for Cascade Kelly Holdings LLC, dba Columbia Pacific Bio-Refinery," Aug. 19, 2014.

13. US Environmental Protections Agency, http://www.epa.gov/ttnchie1/le/benzene_pt2.pdf

14. Vacono Dome, http://www.easyfairs.com/uploads/tx_ef/VACONODOME_2014.pdf

15. Vancouver Energy USA, "Preliminary Draft Environmental Impact Statement (EIS)," Dec. 17, 2014.

16. Platts, "US condensate splitter plans move forward, but uncertainty remains," Aug. 11, 2015.

17. Oneok Partners, "Oneok Partners Announces Completion of More Than $500 Million in Capital-Growth Projects," press release, Oct. 30, 2014.

18. Fox, P., "Air Quality Impacts of the Keystone XL Project at Refineries in PADD 3," prepared for the Natural Resources Defense Council, Apr. 22, 2013.

19. Supreme Court of California, No. S202828, "Neighbors for Smart Rail v. Exposition Metro Line Construction Authority," 304 P.3d 499, 505, Aug. 5, 2013.

20. California Superior Court, "Verified Petition for Writ of Mandate: Association of Irritated Residents, Center for Biological Diversity, and Sierra Club v. Kern County Board of Supervisors and Kern County Planning and Development Department, Oct. 8, 2014, p. 3.

21. California Court of Appeals, "Fairview Neighbors v. County of Ventura," 70 Cal. App. 4th 238, 243, Jan. 28, 1999.

The authors

Gabriel Collins ([email protected]) is a litigation associate in the Houston office of Baker & Hostetler LLP. He worked previously as a commodity investment analyst. Collins is a graduate of Princeton University, New Jersey, and the University of Michigan Law School.

Matthew Lanahan ([email protected]) is an attorney at Arnold & Porter LLP. He is a graduate of Virginia Tech University and the University of Michigan Law School.

Alexander K. Obrecht ([email protected]) is an energy attorney in the Denver office of Baker & Hostetler LLP, focusing on regulatory and litigation matters. He is a graduate of Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass., and the University of Wyoming College of Law.

The opinions and assessments expressed in this piece are the authors' personal views only, are not legal advice, and do not reflect the official positions of Arnold & Porter, LLP or Baker & Hostetler, LLP.