North American production boom pushes crude blending

John R. Auers John Mayes

Turner, Mason & Co.

Dallas

Rapid growth of US and Canadian crude oil production in recent years is exceeding the capacity of pipeline infrastructure to deliver crudes to refiners, causing some crudes to become "stranded." As a result, these stranded crudes have been priced well below competing grades with better market access.

This situation has created several problems along the crude oil supply chain of producers, midstream operators, and refiners. Among these difficulties is the blending of distressed grades to produce mixes that replicate more expensive waterborne crudes, such as Alaska North Slope, Arab Light, and others. This has created the potential for large profits for those refiners that can effectively blend, deliver, and refine the substitute crude blends.

Rising rates

Crude oil production in the US is not only rising, but the rate of that increase is also accelerating. After steadily declining for more than 2 decades and bottoming out at 5 million b/d in 2008, domestic production has made a sharp "U-Turn" and risen by more than 40% to more than 7 million b/d currently, as shown by data from the US Energy Information Administration.

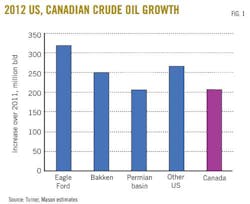

Half of this increase (1.0 million b/d) has taken place only over Dec. 1, 2011, to Dec. 1, 2012, the largest single-year increase in US history. Most industry analysts expect production to continue to rise through at least the end of the decade.

Turner, Mason & Co.'s 2013 North American Crude and Condensate Outlook, to be issued next month, forecasts crude production growth (by volume and grade) for the US and Canada through 2022 and the effects of these increases on refiners. The analysis examines both a low production case (9.0-9.5 million b/d by 2022) and a high case (11.5-12 million b/d in 2022) for the US (Fig. 1).

Crude production has also grown in Canada, increasing by more than 200,000 b/d in 2012 and more than 1 million b/d (50%) since 2000. Almost all of this growth is coming from the gigantic oil sands reserves in Western Canada, and production is likely to continue to grow, possibly increasing by more than another 2 million b/d by 2022.

Rising quality

Perhaps just as important as the volume of the production growth is the quality of the new output. Most of the incremental US production is from emerging shale plays in North Dakota (Bakken) and Texas (Eagle Ford) as well as a resurgence of drilling in older, existing fields, such as the Permian basin, utilizing some of the same improvements in production technologies (fracing and horizontal drilling, among others).

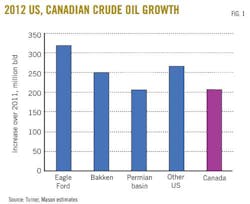

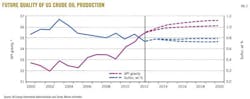

Crude oils from these regions are almost exclusively light (35° API and lighter) and sweet (less than 1% sulfur). US production is going to continue to be predominantly light sweet over the next decade, with the most important exception being modestly strong increases in medium sour production (24-31° API gravity) from the Gulf of Mexico.

Overall, we expect that during the next 10 years, 80% of the incremental US crude oil production will be lighter than 31° API, with much of it lighter than 40° API. These increases will cause the trends of the previous decade of rising gravity and declining sulfur levels to continue. Fig. 2 shows the forecast gravity and sulfur levels and reflects the two cases in the North American crude and condensate study.

By contrast, incremental Canadian production will be from the oil sands of Alberta and overwhelmingly heavy. The combined effects of rising US and Canadian output produce a dumbbell result with strong light and heavy growth but weak medium growth in North America (Fig. 3).

Infrastructure lags

As noted earlier, the rapid increase in US and Canadian production rates has outpaced the development of logistics to deliver crude to refining centers. This has resulted in numerous instances when prices of stranded light US and heavy Canadian grades have been heavily discounted to other grades.

Bakken crude prices have been reduced by the lack of pipeline capacity out of North Dakota, which forced the crude to be priced on a rail basis to the various US coastal markets. Pipeline limitations from the Permian basin to Cushing have caused West Texas Intermediate (WTI) and West Texas Sour (WTS) prices to become disconnected and discounted against other light grades. Even Eagle Ford crude, as close as it is to the massive refining complex along the Gulf Coast, has grown faster than delivery systems. This has resulted in steep pricing discounts that have stimulated barge deliveries to Gulf Coast refineries and vessel movements to the East Coast and even Canada.

Not only are there geographic problems between production areas and refining centers, but the quality of production is also deviating from refining requirements.

In recent years, US refiners have primarily focused on increasing their capacities to process heavier grades through coker and other processing expansions. From projects to be completed over 2011-18, refining demand for heavy crude will increase by more than 900 million b/d, while demand for light crude will decline by about 600 million b/d.

The US Energy Information Administration (EIA) reports that in 2012 the average crude quality processed at US refineries was heavier than 31.1° API, while the gravity of US production rose to 35.4° API. The evolving disconnects between crude production abilities and delivery systems and between production qualities and refining demands have created a growing niche for crude oil blenders to solve both geographic and quality imbalances.

Crude oil blending

The recent pricing disconnects have created opportunities for astute crude oil blenders and refiners to create their own substitutes for waterborne grades at highly discounted prices. A "pseudo" Alaskan North Slope substitute, for example, could be created with a blend of 55% Bakken and 45% Western Canadian Select at a cost potentially far less than the ANS market price.

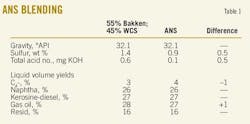

The resulting mix has the same gravity as ANS, slightly higher sulfur, and virtually identical distillation yields. Individual stream properties do have some differences, but not they are insignificant in most cases (Table 1).

Under an example of a blending operation in the Pacific Northwest, the Bakken would be railed from North Dakota and the WCS would be transported on the TransMountain pipeline to one of the Puget Sound refineries (or possibly to Vancouver and then barged to a blending terminal and on to a refinery).

Even with adjustment for these transportation costs, the historical disparities between the costs of a blended "pseudo" ANS vs. actual ANS prices are dramatic. In 2011, an improved margin of $13-15/bbl could have resulted, rising to more than $20/bbl in both 2012 and first-quarter 2013. These values include an allowance for the quality differences between the blended and actual ANS grades. Not included in this calculation are terminal operating costs and expenses in transporting the blended ANS to refining centers (if blending takes place outside of the refinery).

While this type of blending operation can be successfully conducted within a refinery, some refineries do not have sufficient storage or blending capacity. This opens the door for third-party terminal operators to provide a needed role to produce refinery-compatible blends. While ANS would be a logical blend on the West Coast, an Arab Light, Arab Medium, or other waterborne light, sour, or medium crude replacement would be a likely choice on the Gulf Coast, while discussions of a "Philly Light" are already well under way on the East Coast (Table 2).

These economics vividly point out the opportunities that exist today for astute blenders and terminal operators that can act quickly. The dramatic blending margins depend on price-distressed crudes that are unable to reach refining markets in a timely and efficient manner. As pipeline systems improve, blending margins would be expected to decline.

The authors

John R. Auers ([email protected]) is a senior vice-president with Turner, Mason & Co., Dallas. He is the team leader of the Outlook, a biennial report that forecasts supply, demand, and pricing for crude oils and petroleum products worldwide. He also leads assignments in refining economics and planning, LP modeling, downstream asset valuation, crude oil valuation and capital investment and strategic planning. Auers joined the firm in 1987 after 7 years with Exxon Corp., with which he held various positions at its Baytown, Tex., refinery. He holds a BS (1980) in chemical engineering from the University of Nebraska and an MBA (1984) from the University of Houston-Clear Lake. Auers is a licensed professional engineer in Texas and Nebraska and is a member of TSPE and AIChE.

John Mayes ([email protected]) is a senior consultant with Turner, Mason & Co. and specializes in studies and support for the refining industry and other downstream activities. He holds a BS in chemical engineering from Texas A&M University and was previously employed in various refining, supply, and marketing positions with Fina, Ultramar, and BP.