Rising production, exports to boost margins for US refiners

Sandy Fielden

RBN Energy

Houston

US refiners have been blessed with growing domestic and Canadian crude supplies and low operating costs over 2012-13. Replumbing of the distribution system to get these supplies to market is nearing completion–aided by expedient use of rail and barge.

Pricing for crude supplies should favor US refiners as rising US light sweet crude production exceeds demand and refined product exports set higher margins. US refiners willing to invest in reconfiguring their operations to process the growing US production slate will be well-positioned to compete in the near-term international export market for refined products.

Crude supply

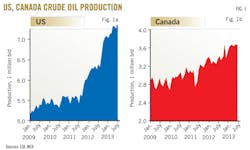

US crude production is surging, up by about 1.5 million b/d since the start of 2009 (Fig. 1a). US Energy Information Administration (EIA) monthly data show July 2013 production just shy of 7.5 million b/d, up 0.4 million b/d since the start of the year after increasing 1 million b/d in 2012.

Much of this new crude production is from tight oil shale basins led by the Eagle Ford, Williston, and Permian. Shale crude production economics in these basins exhibit high internal rates of return, encouraging producers to continue drilling, particularly with prices close to $100/bbl. Production continues to grow even as the number of active drilling rigs is falling because of continued improvements in efficiency.

Data from Canada's National Energy Board1 show crude oil production also increasing but more slowly, up 150,000 b/d in 2013 to July and 0.8 million b/d since January 2009 (Fig. 1b). Most new Canadian production is heavy crude from the Western Canadian Sedimentary Basin destined for US refineries.

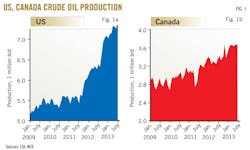

The EIA short-term forecast for October 2013 calls for continued increases in US production (Fig. 2). Most of the increase is in the Lower 48, up 1.1 million b/d to December 2014. Alaskan production of ANS crude is falling by 30,000 b/d/year over 2012-14 to 0.5 million b/d.

Gulf of Mexico offshore production will level out to about 1.32 million b/d in 2013 after recovering from the Macondo accident in 2010. Gulf production will increase during 2014 by 160,000 b/d to 1.48 million b/d. Longer-term, Bentek Energy forecasts US production to reach 10 million b/d and Canadian production to reach 5 million b/d by yearend 2018.2

New production streams are changing the gravity and sulfur content of the slate of crudes that US refiners are processing (Fig. 3). New production from US shale basins has a higher API gravity and lower sulfur content than conventional light sweet crude.

By contrast, new supplies of crude from Canada are heavier, more sour, and diluted by lighter hydrocarbons to make pipeline specification "dilbit" blends such as Western Canadian Select (WCS). Crudes such as WCS have been dubbed "dumbbell" crudes because they contain a mixture of light naphtha and very heavy bitumen with relatively fewer middle distillates.

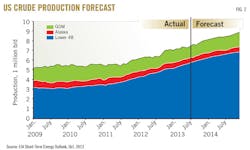

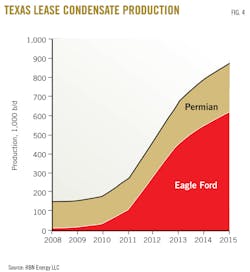

Also notable in the crude production stream will be growing volumes of ultralight sweet crudes variously known as field condensate, lease condensates, or pentanes plus. Classified as crude by EIA, these condensates (50-70° API gravity) are becoming an increasing part of crude production in the Eagle Ford and Permian basins.

Eagle Ford condensate production is up to 500,000 b/d and will be growing by another 150,000 b/d to yearend 2015. The Permian basin has 200,000 b/d of condensate production, to grow by another 30,000 b/d over the next 2 years (Fig. 4).

US refiners will have to adjust their processing capabilities to handle this changing mix of crudes.

Transportation

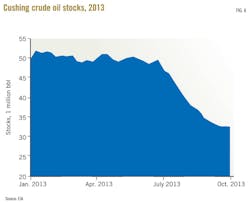

During 2012-13, the US market witnessed a dramatic replumbing of the crude oil distribution system designed to transport new production to market. This replumbing was far from a smooth process. North Dakota and Canadian production in particular overwhelmed the existing pipeline systems in Petroleum Administration for Defense District (PADD) 2, leading to congestion and a large crude stockpile build of more than 50 million bbl at the Cushing, Okla., hub.

(See OGJ, Nov. 4, 2013, p. 90, for an explanation of US PADDs.)

The principal cause of this congestion was that, once crude supplies exceeded PADD 2 refinery needs, incremental production had no path to reach Gulf Coast refiners. This situation initially was addressed through conventional pipeline development projects, including reversals of existing systems such as the Seaway pipeline between Cushing and Houston. These projects proved too slow to alleviate congestion, however, leading producers to pursue alternative transport to get their supplies to market.

The most visible solution adopted, particularly by North Dakota Bakken producers, was loading crude onto rail tank cars (RTCs) for direct delivery to refining regions. During 2012, twenty new rail load terminals were built in North Dakota with nearly 1 million b/d of capacity.

The advantages of rail transport are its speed to market (rapid terminal construction) and its flexibility of destinations—including East and West Coast refineries without current pipeline connections. US crude-by-rail shippers also adopted economies of scale by utilizing "unit" trains with 100 or more dedicated RTCs, reducing the freight cost compared with traditional smaller loads carried in manifest trains mixed with other freight. Data from the North Dakota Pipeline Authority show rail shipments of crude out of North Dakota carried 70% of production volumes by April 2013.3

In 2013, movements of heavy crude from Canada by rail as well as projects initiated to build large rail terminals in Edmonton and Hardisty, Alta., have increased. These terminals are receiving support from producers and refiners because they allow supplies to bypass congested pipelines in PADD 2 and deliver directly to the Gulf Coast. There also have been limited rail movements of heavy bitumen crude from Alberta to the Gulf Coast without using diluent to dilute to pipeline specifications.

By using special insulated and coiled RTCs that are heated on arrival at the destination, shippers can reduce the inconvenience and cost of diluent transport. East Coast refineries with heavy coking capacity have adopted this approach as well.

Efforts to bypass pipeline congestion this year also increased the use of waterborne barges to move crude supplies between US coastal and inland refineries. Barge shipments of crude oil between PADDs 2 and 3 reached 126,000 b/d in July 2013 from about 71,000 b/d in July 2012, according to EIA. The Port of Corpus Christi on the South Texas Gulf Coast reported that coastal barge and tanker movements of crude from the Eagle Ford—mostly headed to Houston or St. James, La., refineries—increased to 387,000 b/d in August 2013 from 50,000 b/d in May 2012.

Transportation constraints continued to restrict the free movement of Canadian and US production to market in third-quarter 2013.4 By second-half 2014, the projected completion of more than 1 million b/d of new pipeline capacity from PADD 2 to PADD 3, together with additional capacity between Chicago and Cushing, will ease the path of crude to Gulf Coast refineries.5

RBN Energy believes it is likely, however, that congestion will simply transfer to the Gulf Coast region as new crude production competes for market share with existing (mostly imported) supplies.5

Midstream infrastructure companies are building additional storage and pipeline connectivity between refining centers on the Texas and Louisiana coasts, but distribution hiccups will take time to balance.6

Crude pricing

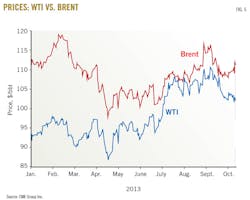

The recent US crude pricing environment has been dominated by the impact of pipeline congestion in the Midwest. This congestion led to a disconnect between US-produced crude priced against West Texas Intermediate (WTI) delivered to Cushing and international crudes imported at the Gulf Coast and priced against the North Sea Brent benchmark.

In June 2010, prices for Brent and WTI traded within $1/bbl of each other. But a build-up of crude inventory at Cushing prompted a deepening in WTI's discount to Brent in August 2010, which grew to as wide as $28/bbl in November 2011 and averaged $18/bbl in 2012.

This year, the WTI discount peaked at $23/bbl in February before narrowing close to parity in July (Fig. 5). Since July, the two crudes traded in a narrower range of $3-$5/bbl before widening again to $9/bbl in late September on US fiscal concerns as well as stronger price support for Brent stemming from geopolitical events in the Middle East and Africa.

WTI's narrowing discount to Brent in 2013 came amid declining WTI volumes in storage at Cushing as more crude was consumed in the Midwest and as pipeline expansions and rail transport relieved congestion at Cushing (Fig. 6).

The price disconnection between WTI and Brent created a two-tier crude refining environment in the US by yearend 2011. Refiners in PADDs 2 and 4 had closer access to crude supplies at discounted prices from the Bakken and Western Canada. Coastal refiners (PADDs 1, 3, and 5) had to pay higher international prices for imported crude volumes priced against the Brent benchmark.

During 2012, the price differential encouraged crude producers to develop alternative transport to reach better-priced coastal markets. This led to increased rail and barge movements as discussed earlier. Coastal refiners had a vested interest in securing lower-priced inland crude supplies instead of paying higher international prices and suffering low margins.

In particular, weak East Coast refining margins in early 2012 led to operating rates of less than 60% of capacity and the threat of closure to Sunoco Inc.'s 300,000-b/d Philadelphia refinery, among others in the region (OGJ Online, July 9, 2012). Shipping less expensive crude from North Dakota by rail to these refineries reduced the threat of closure, and only Hess's 70,000-b/d Port Reading refinery has been shuttered (OGJ Online, Jan. 29, 2013).

Since the narrowing of WTI's discount to Brent in July 2013, the price incentive to move inland crude to coastal refineries has been reduced. By October 2013, Brent prices traded at a premium of $9/bbl over WTI, but the Gulf Coast sweet crude benchmark Light Louisiana Sweet (LLS) and the unofficial West Coast benchmark ANS began to track WTI prices.

Both LLS and ANS traded at premiums of $2-$3/bbl over the Cushing benchmark rather than tracking Brent as they had during the long period of disconnect. This is a taste of things to come, in which US supplies will more than satisfy US refinery demand.

Natural gas pricing

Cheap and plentiful natural gas supplies have led to important consequences for US refiners during 2012-13. Continued record production from shale basins and the slow development of new demand has kept the lid on natural gas prices, which plunged to less than $2/MMbtu in April 2012 after a warm winter resulted in record inventory levels. In 2013, gas prices have recovered to more than $4/MMbtu but are still low by international standards. European equivalent natural gas prices are $11/MMbtu and Asian prices closer to $15/MMbtu.

The consequence of lower natural gas prices is significant to refiners in four ways:

1. Fuel costs for most US refineries that use natural gas are low by international standards. This gives US refiners a competitive cost advantage over international rivals, which currently stands at about $2/bbl compared with their European counterparts.

2. An ongoing wide spread between the prices of natural gas and crude has encouraged NGL production. Increased NGL production has led to low prices for propane and ethane as chemical feedstocks, reducing demand for refined products such as naphtha for this purpose. Propane and butane prices also have declined relative to crude.

3. Oil consumption for heating in the US faces increased competition from cleaner-burning, lower-priced natural gas.

4. Lower prices for natural gas relative to diesel for transport are causing fleet carriers increasingly to consider the use of compressed natural gas as an alternative fuel.

US refined product demand

In contrast to the dramatic surge in US crude supplies, the US demand for refined products continues to decline. EIA data show that US gasoline consumption has been sliding since 2005 and fell by 300,000 b/d in 2012, increasing only slightly in 2013.

Mandated increases in ethanol volumes required under Renewable Fuel Standards (RFS) and higher Corporate Average Fuel Efficiency (CAFE) standards both have added downward pressure on gasoline demand.

As mentioned earlier, low natural gas prices have reduced US demand for naphtha as a chemical feedstock as well as for residential heating oil and commercial road diesel.

Additionally, refined product markets in the US appear set to suffer from continued regulatory pressure on volumes and margins. Although a battle over the ethanol blend wall caused by increasing RFS mandate volumes was resolved by the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) adopting a more conciliatory approach to the issue, proposed Tier 3 gasoline regulations to take effect in 2015 threaten to cause similar conflict over the increased cost of desulfurization (OGJ Online, May 22, 2013; Oct. 11, 2013).

US product exports

The bright spot in US refined product demand continues to be the export market, particularly for middle distillates. According to EIA, net US diesel exports more than doubled to 883,000 b/d in 2012 from 433,000 b/d in 2011. Net average finished motor gasoline exports also increased to 367,000 b/d in 2012, up 200,000 b/d over 2011.

Net exports of these products in 2013 to July remain at similar levels. Most of these exports are from the US Gulf Coast, which is becoming a regional export center.

EIA data show that the destination of refined product exports from the Gulf Coast is primarily Latin America, where growing demand for distillates—especially low-sulfur grades—exceeds refining capacity.

The US has also increased exports of middle distillates to European markets, which lack sufficient regional capacity for producing jet kerosene and diesel.7

Gulf Coast refiners have the advantages of lower priced, US-produced crude supplies as well as cheap natural gas fuel in producing competitively priced exports. The sophistication of Gulf Coast refineries is also an advantage as environmental regulations continue to require further reductions in sulfur levels. US refiners, such as Valero Energy Corp., have increased their hydrocracking capability by using hydrogen from natural gas as a feedstock to produce ultralow-sulfur diesel.

US refining

The rapidly changing US crude supply picture requires refiners to consider investment plans to process the expanding slate of Canadian and US crudes arriving by way of new infrastructure. This need for reconfiguration likely will be felt most keenly on the Gulf Coast, where increasing supplies of light sweet shale crude and heavy Canadian blends will be heading next year.

Since many Gulf Coast refineries invested heavily over the past 10 years to increase their conversion capacities to handle heavy sour crudes, they are not prepared for the flood of light crude. Already, US refiners contend with unwanted light hydrocarbons used as diluents blended with heavy Canadian crude supplies.8

Some changes in refinery configuration are already under way. Refiners have announced plans to increase their topping capacity to handle greater volumes of light crude. Others are planning to build condensate splitters that are basic distillation units.

As increasing volumes of new crudes arrive at Gulf Coast refineries in 2014, it seems likely that downward price pressures will encourage refiners to process these crudes, even if their refineries are not ideally equipped to do so, by reducing throughputs to handle a lighter, sweeter crude mix. Those refiners that adapt their configurations to handle greater light sweet crude volumes will benefit the most.

US refiners will process almost all of the rising US crude production as a result of the federal ban on exporting crude oil from the Lower 48 (except for limited volumes to Canada under license). If that export ban remains, refiners will have little choice but to adapt their configurations to the new crude slate.

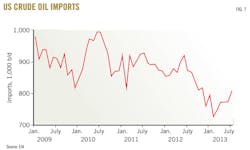

Increased US production will largely replace crude oil imports, which fell by 700,000 b/d in July 2013 compared with July 2012, according to EIA data (Fig. 7). On the Gulf Coast, light sweet crude imports have already been backed out by shale crude from the Bakken, Eagle Ford, and Permian basins. Bakken crude delivered by rail and barge is also backing out imports of light crude to the East Coast. In the Northwest, refiners are replacing overseas imports as well as ANS deliveries with a mixture of Bakken light sweet and Canadian heavy crudes.

Refiners and midstream developers are also proceeding with plans to deliver supplies of US light sweet and Canadian heavy crude to California refineries by rail or barge.9 If these plans overcome state permitting issues, then California refineries should begin to enjoy greater diversity of supply and replace additional imported volumes. The viability of the recently instituted California low-carbon fuel standard regulation on the crudes processed in the state's refineries still remains undetermined but will have repercussions for California refiners (OGJ Online, Sept. 19, 2013).

US refineries' access to heavy Canadian crude supplies continues to be constrained by a lack of pipeline access and delays in approving the Keystone pipeline expansion. When these transportation difficulties are overcome, imports of heavy crude from Mexico, Venezuela, and the Middle East should decline accordingly.

PADD 2 refiners will continue to enjoy the advantage of closer access to crude production from the Bakken and Western Canada as well as increased supplies from West Texas, the Rockies and the Anadarko basin. PADD 2 refining margins, however, are now lower than they were in the past 3 years because the WTI discount to coastal crudes has narrowed.

In fact, since the narrowing in WTI's discount to Brent this year, refining margins have fallen across the US even as EIA data indicated that refinery utilization rates in PADD 3 routinely exceeded 90%. This has resulted from WTI's return to international price levels during the same period that product prices remain flat or falling.

As long as exports continue to set the price of refined products, increasing supplies of US crude competing to supply Gulf Coast refineries should keep prices lower than international levels and improve US refining margins.

For the moment, prospects for US refining look positive, as demonstrated by the first greenfield capacity in 40 years scheduled to start up in North Dakota by yearend 2014 (OGJ Online, Feb. 7, 2013; Mar. 27,2013). But reduced US demand for refined products will continue to pose a challenge if export markets weaken.

International refining

In contrast to Europe, where refining capacity is declining, the US should continue to be competitive in international markets due to lower crude supply costs and more sophisticated capacity.

But the export market for refined products is changing as countries that formerly exported crude oil are now investing in refining capacity to increase the value of their resources. US refiners increasingly will have to compete with new refining capacity in the Middle East (Saudi Arabia) and Russia as competition mounts to secure markets for refined product exports to destinations in Europe and Asia-Pacific.

References

1. National Energy Board, "Estimated Production of Canadian Crude Oil and Equivalent," Aug. 15, 2013, accessed November 2013 (www.neb-one.gc.ca).

2. Williams, Jay, "Crude Oil Market Update," Desjardins Capital Markets Commodities Outlook Conference, May 2, 2013, Toronto.

3. North Dakota Pipeline Authority, "Estimated North Dakota Rail Export Volumes," August 2013, accessed November 2013 (www.dmr.nd.gov/pipeline/index.asp and http://northdakotapipelines.com/rail-transportation).

4. "Canada crude—Heavy and synthetic grades weaken further," Reuters, Oct. 3, 2013 (www.reuters.com).

5. "I'm Waiting for the Crude—Handling the Texas Gulf Coast Crude Flood," RBN Energy, Nov. 3, 2013 (www.rbnenergy.com).

6. "Gulf Coast Crude Oil Flood Preparations: The Terminal Operators," RBN Energy, Jan. 29, 2013 (www.rbnenergy.com).

7. "Diesel/Gasoline Imbalance," Fueling Europe's Future, The European Petroleum Industry Association, accessed November 2013 (www.fuellingeuropesfuture.eu).

8. Yamaguchi, Nancy, "Shifting challenges in heavy crude," Energy Global, Feb. 22, 2013 (www.energyglobal.com).

9. "Coast Bound Train—The Future of Crude By Rail to the West Coast," RBN Energy, Sept. 29, 2013 (www.rbnenergy.com).

The Author

Sandy Fielden([email protected]) is managing director of Energy Analytics at RBN Energy, Houston. He has previously held positions as vice-president for data services at Allegro Development Corp., vice-president for energy products and services at LIM (now Morningstar Commodity Data), and product manager at Saladin. Fielden holds a degree in international history from the University of Leeds, UK, and an MBA from the University of Bradford. He is a member of the first graduating class for the Global Association of Risk Professionals (GARP) Energy Risk Professional (ERP) qualification.

Manuscripts welcomeOil & Gas Journal welcomes for publication consideration manuscripts about exploration and development, drilling, production, pipelines, LNG, and processing (refining, petrochemicals, and gas processing). These may be highly technical in nature and appeal or they may be more analytical by way of examining oil and natural gas supply, demand, and markets. OGJ accepts exclusive articles as well as manuscripts adapted from oral and poster presentations. An Author Guide is available at www.ogj.com, click "home" then "Submit an article." Or, contact the Chief Technology Editor ([email protected]; 713/963-6230; or, fax 713/963-6282), Oil & Gas Journal, 1455 West Loop South, Suite 400, Houston TX 77027 USA. |