State companies hold power over Chinese energy policy

Xiaofei (Sarah) Li

York College of Pennsylvania

York, Pa.

Two important aspects of the energy policymaking system have shaped China's energy policies: the weakness of central government institutions involved in energy and the power of state-owned energy enterprises.1 This imbalanced situation has hampered coordination among opposing interests in the energy sector, stunted the growth of a comprehensive Chinese energy strategy, and permitted China's state-owned energy enterprises to strongly influence China's energy policy.2 3

Because of this, it is the corporate interests of the Chinese energy firms rather than the national interests of the Chinese state that drive China's energy agenda.4

Reforms in the '90s

In the mid-1990s, there were shifts in the oil industry and increased regulation of the price of domestic oil. These changes took place, at least in part, to create oil companies that were financially sound, adaptable to market conditions, and able to actively engage in imports and investment overseas. As a result, the three largest Chinese-run oil companies ascended to the ministerial level: China National Petroleum Corp. (CNPC), China National Petrochemical Corp. (Sinopec), and China National Offshore Oil Corp. (CNOOC).

The national oil companies (NOCs) came under control of the State Economic and Trade Commission. They received the right to form smaller companies that would engage in oil exploration overseas. To fund this work, the Chinese government increased the controlled price of crude oil. From 1993 until 2003, when former Prime Minister Zhu Rongji was in control of China's economic policies, CNPC, Sinopec, and CNOOC became increasingly powerful.5

The companies grew within a government in which authority is divided among several agencies.

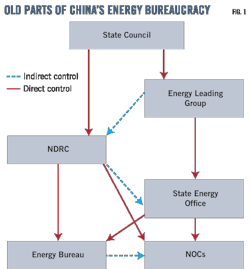

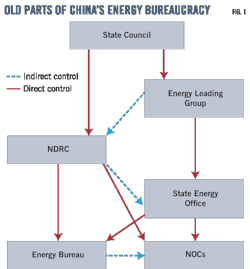

The agency with the most power is the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC). This agency controls the planning of long-term energy development, the setting of energy prices, and the approval of investments in domestic and international energy projects. The NDRC has at least seven offices that oversee the oil sector, among them the Energy Bureau.6

Other government agencies that deal with oil policymaking include:

• The Ministry of Land and Resources, which is in charge of surveying natural resources, including oil and gas, and which grants licenses for exploration and production.

• The Ministry of Commerce, which issues licenses for the import and export of oil and which regulates foreign firms investing in China's energy markets and Chinese firms investing abroad.

• The Ministry of Finance, which makes tax and fiscal policies that promote the energy objectives of the central government.

• The Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA), which supports the NOCs in their attempts to acquire opportunities in trade and investment abroad. This is part of the MFA's larger mission to promote commercial relations with other countries. The MFA also tries to ensure that deals pursued by the NOCs do not run afoul of other foreign policy objectives.

Regulatory structure

The current regulatory structure developed after Zhu, the former prime minister, abolished the Ministry of Energy in 1993 because he wanted the energy sector to be exposed to market forces. The NDRC established the Energy Bureau in 2003 out of a perceived necessity for an efficient institutional authority. Although the Energy Bureau was given a rather expansive mandate, it received relatively little manpower or practical authority.7

The National People's Congress established the State Energy Office (SEO) and the National Energy Leading Group (ELG) in 2005.8 The balancing of the interests of the various stakeholders is always the most challenging aspect of changing the institutional structure of energy policymaking.9

The NDRC's establishment of the Energy Bureau was a compromise between several important players in China's energy bureaucracy.10 The ability of the Energy Bureau to manage effectively China's energy sector has been limited by its lack of resources and political influence. What is more, since it is an agency within the NDRC, the Energy Bureau lacks the power to coordinate among other politically influential entities, such as the NOCs and other ministries.11

The Chinese government created two institutions in 2005 for energy policymaking: the ELG and its administrative body, the SEO. The agencies were created to help China improve its energy-policymaking system.

A degree of enmity has emerged between the MFA and the NDRC and between the MFA and the NOCs. Chinese diplomats from the MFA have often complained that they do not find out about investments made by China's NOCs until after the fact.12 These complaints are grounded in the diplomats' concern about the impact of NOC investments on larger foreign policy objectives. It was in response to the MFA's concerns that the ELG and SEO were established. Supporters of the move favored the establishment of a supraministerial body to consolidate authority over the energy sector and to work in concert with other government agencies involved in energy, such as the MFA.13

The ELG and SEO

The ELG was created under the State Council led by Premier Wen Jiabao; the SEO reported directly to the premier. The creation of these agencies showed that the leadership was dissatisfied with the energy policymaking structure in place at the time. An objective was to reduce the influence of the energy firms. Since China's top leaders realized that a ministry would in all probability become another layer of bureaucracy controlled by vested interests, they decided to form a leading group rather than a ministry.14

The importance and power of the ELG were substantial. The ELG had among its ranks some of China's most powerful officials. A leading group's recommendations usually represent a consensus by the leading members of the government, party, and military agencies.15 The ELG thus was able to intervene in the energy sector to solve problems as they arose.

The ELG was not, however, involved in the day-to-day running of the energy sector. The responsibilities of the primary government and party positions of ELG members prevented them from routinely getting involved in conflicts of interest that hamper energy-policy formulation.16 Leading groups do not promulgate concrete policies. Rather, they issue guiding principles about the overall direction in which bureaucratic activity should proceed.17

The SEO was not particularly powerful politically. It had the bureaucratic rank of a vice-ministry, below that of the NDRC and some of the NOCs.18 The SEO had a vague mandate, overlapping that of the NDRC Energy Bureau. Some critics have described the SEO as a paper-tiger policy-consulting body that merely encouraged the writing of reports.19

New policymaking structure

The National Energy Administration (NEA) and the State Energy Commission (SEC) were two additions to China's energy bureaucracy made by the National People's Congress in 2008. Among other changes, the ELG was to be replaced by the SEC, although the staffing and organization have yet to be determined (Fig. 2).

The NEA was created, at least in part, to handle the daily affairs of the SEC. The NEA was also a vice-ministerial successor to Energy Bureau of the NDRC. Since it was not given sufficient manpower and effective authority, the NEA, although given a mandate to do so, would struggle to cope with the energy challenges facing China. In this respect, it is similar to its predecessor, the NDRC Energy Bureau.20

In general, China's energy governance is not likely to be improved substantially by the country's new energy administration. Although its outward structure seems changed, the energy bureaucracy still has many limitations.

It is thus expected that business as usual will continue: Effective decision-making will be impeded by conflicts of interest; policies and projects will continue to be determined almost exclusively by the energy companies; shortfalls in the domestic energy supply will continue to arise because of energy prices that are set by the state; and the NEA will continue its attempts to address these shortfalls, although it lacks the power to adjust energy prices as needed.21

NOC activism

There is no single institution in China with the power or ability to coordinate the interests of the various stakeholders. As a result, energy governance in China has been subject to fragmented energy policymaking.22 In response to this fragmentation, there have been calls for the institution of a Ministry of Energy. However, certain ministerial and corporate interests oppose the proposal.

These interests have been led by the NOCs and the NDRC.23 As a result of their influence, China has been unable to make significant changes in its energy policymaking apparatus.

Fragmented energy policymaking means that China's NOCs have been engaging in activism, as opposed to the stagnation that pervades the energy bureaucracy. This activism is fueled by the political, human, and financial resources that the companies possess but which the energy bureaucracy lacks.

These NOCs' profitability, international subsidiaries, expertise in their industry, and executives in the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party have contributed substantially to their influence.24 Chinese energy firms have initiated such projects as the West-East Pipeline and the acquisition of foreign energy assets.25 These projects were only later embraced by the Chinese government.

At times, the companies have even ignored national interests in favor of their own corporate interests. For example, China's NOCs have made their own determination about overseas investments, turning a deaf ear to advice from the central government.

With increased financial and administrative autonomy, and facing fragmented regulation from the government, the Chinese NOCs have been able to join their own financial interests in specific projects to a professed interest in Chinese national "energy security." As a result, some projects of the NOCs in effect drive policy.26

References

1. Downs, E., "The Brookings Foreign Policy Studies Energy Security Series: China," The Brookings Institution, December 2006, p. 16.

2. Tian, M., "New Authority to Oversee Energy Sector," China Daily, Apr. 30, 2005, Dow Jones; and Chung, O., "High-level office to tackle China energy shortages," The Standard, Jan. 12, 2005.

3. Hui, H., "The National Energy Leading Group is only the first step," (Guojia nengyuan lingdao xiaozu zhi shi di yi bu), pp. 40-42; Yichao, W., "China's energy sector moves from crisis to new administration," (Zhongguo nengyuan cong weiji dao xinzheng), Caijing, No. 23, 2005; and "China to set up energy regulator under SDRC," Reuters News, Mar. 28, 2003.

4. See Andrews-Speed, P., "Energy Policy and Regulation in the People's Republic of China," Kluwer Law International, 2004, p. 56, and Chapters 5 and 12.

5. Troush, S., "China's Changing Oil Strategy and its Foreign Policy Implications," Center for Northeast Asian Policy Studies, The Brookings Institution, at http://www.brookings.edu/articles/1999/fall_china_troush.aspx.

6. Ting, C., "The Energy Bureau's Dilemmas" (Nengyuan ju kunjing), 21st Century Business Herald (21 Shiji jingji baodao), May 10, 2004, at www.nanfangdaily.com.cn/jj/20040510/chj/200405100076.asp.

7. Downs, E.S., "China's Energy Policies and Their Environmental Impacts," U.S.-China Economic & Security Review Commission, John L. Thornton China Center, The Brookings Institution, at http://www.brookings.edu/testimony/2008/0813_china_downs.aspx.

8. Ibid.

9. See "The New Energy Institution: Ministry of Energy or Energy Supervision and Management Commission?" (Xin nengyuan jigou: nengyuanbu haishi nengyuanwei?), China Entrepreneur (Zhongguo qiyejia), Feb. 6, 2005; and Yichao, W., "The Case of the Energy Bureau: Will it be a transitional product long in the making?" (Nengyuanju zhi ju: hui shi yige manchang guodupin ma?), Caijing, No. 8, Apr. 20, 2003.

10. "Will China Reestablish the Ministry of Energy?" (Zhongguo chongjian nengyuanbu?), Business Watch Magazine (Shangwu zhoukan), May 5, 2005, p. 51.

11. Chung, O., "High-level office to tackle China energy shortages;" and "China delays setting up Ministry of Energy due to complexity of problems," Agence France Press, Dec. 3, 2004.

12. Downs, December 2006, p. 19.

13. This section summarized Downs, December 2006, pp. 16-18.

14. Interview with industry insider, Beijing, Apr. 12, 2006, in Downs, December 2006, p. 20.

15 Downs, December 2006, pp. 20-21.

16. This paragraph referred to Downs, December 2006, p. 21.

17. Huang, J., "Factionalism in Chinese Communist Politics," Cambridge University Press, 2000, pp. 414-17; and Lieberthal, K., and Oksenberg, M., "Policy Making in China: Leaders, Structures and Processes," Princeton University Press, 1988, pp. 26-27.

18. Ibid., p. 20.

19. "Calls for upgrading the NDRC Energy Bureau to a general energy directorate are heard again," (Guojia Fagaiwei jiang shengge wei guojia nengyuan zongju de shengyin youqi), Economic Observer (Jingji guancha bao), Feb. 19, 2006.

20. Downs, E.S., "China's Energy Policies and Their Environmental Impacts," U.S.-China Economic & Security Review Commission, John L. Thornton China Center, The Brookings Institution, at http://www.brookings.edu/testimony/2008/0813_china_downs.aspx.

21. Ibid.

22. Ibid.

23. Ibid.

24. Ibid.

25. Ibid.

26. Huang, J., "Factionalism in Chinese Communist Politics," Cambridge University Press, 2000, pp. 414-17; and Lieberthal, K., and Oksenberg, M., "Policy Making in China: Leaders, Structures and Processes, Princetion University Press, 1988, pp. 26-27.

The author

More Oil & Gas Journal Current Issue Articles

More Oil & Gas Journal Archives Issue Articles

View Oil and Gas Articles on PennEnergy.com