Nick Snow

Washington Editor

Natural gas produced from shale appears certain to increase its share of total US supplies, but other sources can contribute significantly if they're allowed to compete, according to two trade association officials and one official in the office overseeing the federal government's role in constructing a pipeline from Alaska.

"Shale is a game-changer, but it won't be produced all at once. It will take a century to get it all out," said Natural Gas Supply Association Pres. R. Skip Horvath. "The move to shale is gradual, but it's inevitable," he said.

Gas that has been produced from conventional traps since 1860 migrated there over centuries from deeper shale formations, which only recently have begun to be tapped, Horvath explained. Independent producer George P. Mitchell began to intensify the effort to produce this deeper gas in the 1980s, but it really didn't become economical until the early 2000s with horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing. "It should be embraced, not feared," Horvath suggested.

"Shale is a game-changer, but it won't be produced all at once. It will take a century to get it all out. The move to shale is gradual, but it's inevitable."—R. Skip Horvath, president, Natural Gas Supply Association

When the US Energy Information Administration released its draft 2011 Annual Energy Outlook on Dec. 16, it said a higher estimate of US shale gas resources was supported by more production at prices below estimates in the 2010 AEO. In the 2011 AEO's reference case, the technically recoverable unproved US shale gas resource of 827 tcf was 480 tcf more than a year earlier because of more drilling in new and existing plays.

"The larger resource leads to about double the shale gas production and over 20% higher total Lower 48 gas production in 2035, with lower gas prices than were projected in the AEO 2010 reference case," EIA said.

Bigger gas role

More demand for shale gas appears likely as overall gas consumption climbs worldwide, two multinational oil companies said in their recent annual outlooks. "The forecast shows a shift toward gas as businesses and governments look for reliable, affordable, and cleaner ways to meet energy needs," ExxonMobil Corp. Chief Executive Officer Rex W. Tillerson said as that company released its forecast on Jan. 28. "Newly unlocked supplies of shale gas and other unconventional energy sources will be vital in meeting this demand."

"Shale will take an increasing share of the US market, but it won't squeeze everyone else out. We just need to be competitive on prices."—Larry Persily, federal coordinator, Alaska Natural Gas Transportation Projects Office

BP PLC, when it released its outlook to 2030 on Jan. 19, said its base case projected more growth in electricity generation than transportation demand, and that gas will generate more of that power because it has roughly half of coal's carbon footprint. "We project gas to be the fastest growing fossil fuel, growing by some 2.1%/year," BP Chief Executive Officer Bob Dudley said.

In the shorter term, however, onshore conventional gas production, which EIA said in its 2010 AEO represented 64% of the US total in 2009, will remain dominant, Horvath said. Growing demand for gas to produce electricity, combined with more shale gas production, made the rate of storage addition triple from 2006 to 2010 because salt domes can be recycled more frequently to meet peak power demands, he added. "The market infrastructure adjusted to shale with more storage," he said.

In its 2011 AEO advance release, EIA conceded that shale gas production growth uncertainties exist. "Well characteristics and productivity vary widely not only across different plays but within individual plays," it said. "Initial production rates can vary by as much as a factor of 10 across a formation, and the productivity of adjacent gas wells can vary by as much as a factor of 2 or 3. Many shale formations, such as the Marcellus shale, are so large that only a small portion of the entire formation has been intensively production-tested. Environmental considerations, particularly in the area of water usage, lend additional uncertainty."

The forecast also dropped a pipeline to transport gas from Alaska to the Lower 48, which the 2010 AEO said would be completed in 2023, because of higher assumed capital costs and lower gas wellhead prices. EIA said these high costs and lower prices make the project uneconomical over the forecast period to 2035. That concerns Larry Persily, federal coordinator of the Alaska Natural Gas Transportation Projects Office, who thinks consumers in the Lower 48 will need gas from Alaska's North Slope.

Price-competitive

"Would I bet on shale gas as the Holy Grail of domestic supplies? Hardly, particularly in the Marcellus shale where there hasn't been that much oil and gas activity," Persily told OGJ. "Rigs and compressors make noise. Opposition has grown. Shale will take an increasing share of the US market, but it won't squeeze everyone else out. We just need to be competitive on prices."

"All that the LNG industry asks is to have a legislative and regulatory framework which allows it to compete in the global marketplace. We think we have it now."—Bill Cooper, president, Center for Liquefied Natural Gas

A 3,000-mile pipeline could be built from Alaska based on prices in a $6.50-7/Mcf range because production would be significantly less than from shale formations, Persily said. The challenge stems from it being at least 10 years before the gas would start flowing through the system, he noted. "As a producer, you would need to be very comfortable spending $40 billion on one project than $10 billion on four projects. Alaska's tax structure also is more aggressive than other states'," he said.

Alaska Gov. Sean Parnell proposed changes to the state's oil and gas tax rates on Jan. 17, including a lower rate for areas outside current fields and a cap to overall production tax rates to encourage more production. Persily said two separate groups (with TransCanada Pipelines and ExxonMobil in one, and BP and ConocoPhillips in the other) are moving ahead, but probably will need a contractual commitment from the state before securing 25-year firm shipping commitments from customers.

"I'm realistic. It's possible that gas could flow from Alaska to the Lower 48 in the 2020s, but not probable," he said. "I try to explain to Alaskans what will be needed to get this project done. That state tax take is a big question, and the companies want to nail that down. They want certainty. They want projects with the highest returns and least risk. Right now, we're not at the top of that list." If the US increasingly turns to gas to generate electricity, if shale gas can't meet all the needs, and if Alaska can demonstrate that it's competitive, the project could happen, Persily said.

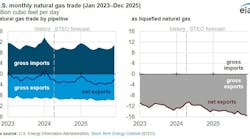

Although net pipeline imports of gas from Canada and Mexico declined to lower levels in 2035 under EIA's preliminary 2011 reference case, cumulative net import volumes are higher largely because of a decrease in Canada's domestic consumption and an increase in the country's assumed shale gas resources and production.

LNG imports

LNG imports in the preliminary 2011 AEO's reference case weren't as great as they were in the 2010 draft AEO's, partly due to less world liquefaction capacity and greater world regasification capacity, as well as more LNG use outside North America. "For example, spot market purchases of LNG in Europe are expected to displace pipeline gas supplies that are indexed to world oil prices. Lower gas prices in the United States are also a contributing factor," it said.

LNG still is part of the overall US gas picture, particularly in the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic states and along the Gulf Coast to a degree, according to Bill Cooper, president of the Center for Liquefied Natural Gas. The Distrigas terminal in Everett, Mass., supplies roughly 25% of New England's gas and, on very cold days, 40%, he said. "The Northeast's pipeline structure is underdeveloped relative to its demand. Historically, LNG is moved by truck to facilities which regasify it and use it as a peak-shaving device in the wintertime," Cooper told OGJ.

Cooper said the decline in the number of proposed import terminals is the logical progression of LNG's development in this country. It started with recognition in 2003-04 that more gas from outside the US would be needed in the future than would be available by pipeline from Canada or Mexico. A 2003 National Petroleum Council study said that 7-9 new terminals and expansions of existing facilities would be needed. "Today, we have 10, and several have fallen by the wayside," he said. "It's been a natural progression as the market has moved forward."

Cooper said US legislation and regulations have allowed LNG terminal sponsors to get permits and build regasification facilities, usually where pipeline infrastructure existed or could be constructed. "The next test will come for export facilities. I see the process there working the same way," he said, adding, "All that the LNG industry asks is to have a legislative and regulatory framework which allows it to compete in the global marketplace. We think we have it now."

NGSA's Horvath said the US is a long way from having to worry about getting too much of its gas from a single source. Federal policies which significantly restrict production from public lands, which primarily is from conventional deposits, possibly could encourage more shale gas production since those formations mostly are on private property, he suggested.

Backing up alternatives

Gas provides an ideal backup to solar, wind, and other alternative electricity sources, which are intermittent, but it has to make money doing so, Horvath said. "The rules and regulations need to be there so there's a fair incentive to build these gas plants," he said, adding that gas also can increasingly provide ancillary services to keep electricity services reliable with steady voltage, although price caps could jeopardize that service if they are imposed.

"Some power generation customers feel they're being forced to use gas instead of coal. We want to assure them it's a good choice," he said, noting that volatile prices are inherent in any commodity and that gas has been no worse than others over time but has wound up at a lower price largely because of shale formations' potential.

"The freshmen coming into Congress have already shown an unusual willingness to learn about natural gas," he told OGJ. "Many other policymakers don't understand the issues, and that's the industry's fault. We need to educate them better. The same person can flip from treating gas as the default fuel to making it the forgotten fuel. That's what we're trying to overcome.

"I'm excited," Horvath added. "We're positioned to meet power generation and industrial customers' growing needs, and residential and commercial demand is holding steady. You can still see commercial market anomalies, but for our baseload, we're pretty confident we can stay competitive."

Shale is the biggest reason why, he maintained. "It's the source rock. It's going to be an old man before we say goodbye to it," Horvath declared.

More Oil & Gas Journal Current Issue Articles

More Oil & Gas Journal Archives Issue Articles

View Oil and Gas Articles on PennEnergy.com