LNG figures heavily in Japan's postdisaster energy demand

Tomoko Hosoe

East-West Center

Honolulu

The 9.0 magnitude Great East Japan Earthquake followed by tsunamis on Mar. 11, 2011, in Tohoku affected not only Japan's energy industries, including damage to basic infrastructure of nuclear power plants, but also long-term policy.The electric utilities directly affected by the disasters—Tokyo Electric Power Co., Tohoku Electric Power Co., and Japan Atomic Power Co.—lost much of their base load nuclear power generation capacities, either permanently or temporarily.

Other utilities that own nuclear power plants are also affected. Their nuclear plant utilization rates are falling, as they must conduct inspections on existing nuclear plants to ensure plant safety and emergency preparedness.

While the extent and duration of nuclear plant shutdowns remain unknown, it is certain that demand for other fuels, primarily LNG, will continue increasing, while power-saving efforts will escalate throughout Japan.

Nuclear plants' status

Table 1 lists nuclear power plants owned by Tepco, Tohoku Electric Power, and Japan Atomic Power in the disaster areas. None of the plants listed is operating as of today.

Altogether, Tepco owns three nuclear power plants: 4.7-Gw Fukushima Daiichi, 4.4-Gw Fukushima Daini in Fukushima Prefecture, and 8.2-Gw Kashiwazaki-Kariwa in Niigata Prefecture. The Kashiwazaki-Kariwa plant was not affected by the disasters, while Fukushima Daiichi and Fukushima Daini completely stopped functioning.

Of the total 9.1-Gw capacities in Fukushima Prefecture, 6.4 Gw were in operation at the time of the earthquake and tsunami, while others (Fukushima Daiichi 4-6) were under maintenance. Tepco has officially decided that four units (Fukushima Daiichi 1-4) will be dismantled. It is also reasonable to believe that the remaining six units (Fukushima Daiichi 5-6 and Fukushima Daini 1-4) will be out of circulation indefinitely.

Tohoku Electric Power owns two nuclear power plants: 2.2-Gw Onagawa and 1.1-Gw Higashi-dori. Two units (total capacity 1.35 Gw) of the three at the Onagawa plant were in operation at the time of the Mar. 11 disasters, while the rest at Higashi-dori and Onagawa units were under maintenance. With the information at hand, we expect the Onagawa plant, in Miyagi Prefecture, to remain closed for a few years, and the Higashi-dori plant in Aomori Prefecture may be able to resume operation sooner.

Japan Atomic Power's 1.1-Gw Tokai Daini nuclear plant in Ibaraki Prefecture and 1.2-Gw Tsuruga-2 in Fukui Prefecture have been offline since Mar. 11. (Tsuruga-1 had been under maintenance.)

Following the Fukushima crisis, at the request of Prime Minister Naoto Kan, Chubu Electric Power closed two units (4 and 5) of its Hamaoka nuclear power plant on May 13, 2011, while Unit 3—currently under maintenance—will remain closed. Therefore, the 3.6-Gw Hamaoka plant will be completely closed until Chubu Electric completes a breakwater and other tsunami- and quake-protection measures around the plant. It is expected to take 2-3 years for the completion.

The prime minister thought it necessary to ensure the safety of the Hamaoka plant because a government agency (before the Fukushima disasters) had predicted an 87% chance of the large-scale earthquake occurring in the Tokai region, where the Hamaoka plant is located, in the next 30 years.

Currently, various nuclear units are under maintenance, inspection, or both throughout Japan. In summary, only 19 of Japan's total 54 nuclear units are operating, with Japan's average nuclear plant utilization at 36%.

The average utilization rate will fall further unless the reactors (currently under maintenance or inspection) resume operation, especially as more units will be shut down for maintenance in the next few months. Nuclear reactors normally go through a 90-day maintenance cycle every 13 months. By early August, three units (a total capacity of 3.15 Gw) are to be shut down for maintenance followed by an additional four units (a total capacity of 3.4-Gw) to be closed by early September. The situation is expected to worsen toward summer as Prime Minister Naoto Kan on July 6 announced new "stress tests" for nuclear reactors nationwide. The government believes stress tests, which are expected to use computer simulation to evaluate a reactor's resilience to different disasters beyond its current design capacity, could give the general public a better sense of nuclear plant safety. Yet it remained unclear how long such tests will take and how local authorities and community would judge the test results.

It remains in question as to how soon nuclear units can resume normal operations; Japan has never before experienced nuclear power problems on this scale. In other words, the country has no way of assessing how soon utilities could receive permission from local authorities and local communities to resume nuclear plant operations as the general public's trust in nuclear power and the government has been lost.

Thermal power plants' status

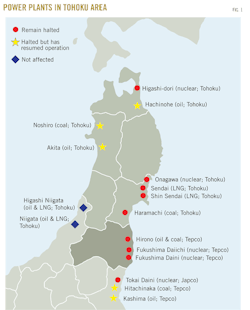

Table 2 lists thermal power plants owned by Tepco and Tohoku Electric Power. As shown, some of Tepco's power plants halted operation on Mar. 11; however, all of them (except for the Hirono plant) have resumed operation. Hirono has five units, of which four (total capacity 3.2 Gw) consume fuel oil, crude oil, or both, and one 600-Mw unit consumes coal. Tepco brought back the coal-fired unit in June and planned to bring back the remaining units in full operation before the summer peak season this year. With Hirono's restart, Tepco will have brought back all its thermal power plants.

As for Tohoku Electric, five units (total capacity of 3.4 Gw) listed in the table remain closed. The duration of the plant shutdowns remains unknown, given that the plants are in the disaster areas.

Fig. 1 illustrates geological locations of nuclear and thermal power plants owned by Tepco and Tohoku in the disaster areas. It is important to note that all of Tepco's coal and fuel oil and oil-fired plants lie outside Tokyo.

Effects on regional power demand

Power sales in Tokyo and Tohoku fell significantly due to supply disruptions after the disasters. Tepco's power sales volume declined by 6% year-over-year (y-o-y) in March and by 14% y-o-y in April, while Tohoku's sales fell by 14% y-o-y and 20% y-o-y in March and April, respectively (Table 3).

Sales volumes to industrial users in Tokyo fell by 18% y-o-y in March and by 12% y-o-y in April. In Tohoku, sales volumes fell by 14% y-o-y in March and by 20% y-o-y in April. The April decline resulted not only from supply disruptions but also from energy conservation, particularly in Tokyo. Some plants and manufacturers had to increase plant operations in other regions, such as Kansai and Kyushu, to make up the loss of manufacturing bases in the disaster areas.

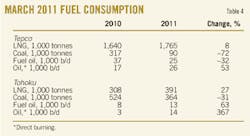

Table 4 summarizes fuel consumption in March by Tepco and Tohoku Electric. As previously discussed, both Tepco and Tohoku lost a significant amount of coal-fired generation capacities in March and increased LNG consumption to make up those losses.

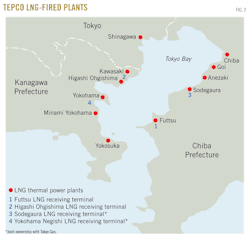

As Fig. 2 illustrates, all of Tepco's LNG-fired plants and LNG terminals are on Tokyo Bay, away from the disaster center and were not affected. However, there is a physical limit to Tepco's LNG import capability, as the port authority will not allow an unlimited number of LNG tankers within the already congested bay. Furthermore, considering Tokyo's strict monitoring and management of photochemical smog issues, Tepco's LNG imports should be limited at around 24 million tonnes/year unless special arrangements are made.

Primary energy demand outlook

In the long run, Japan's primary energy consumption (PEC) mix will change significantly from 2010, while the total PEC will likely fall in light of Japan's looming fundamental structural changes: the country's shrinking population, strict energy-conservation policies, and greater efficiency regulations. Japan's existing energy policy, which focused on expanding nuclear power's share, will be revised.

While specific details of revisions to be made remain unknown, Prime Minister Kan wants the new energy policy to consist of four pillars—energy conservation, fossil fuels, renewables, and nuclear power. While the Kan administration remains committed to nuclear power, existing government targets of 50% of Japan's electricity from nuclear power by 2030 will have to be revised downward. Under such a scenario, 12-14 nuclear units would need to be built and the utilization ratios of the operating nuclear units would need to increase to 85-90%. Currently, the utilization rate is 36%.

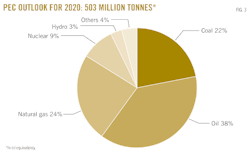

We forecast that the share of natural gas in Japan's PEC will reach 24% in 2020 (from 18% in 2010), based on the assumption that no new nuclear reactor will be built for the forecast period (Fig. 3). The 2020 shares of oil will be 38% (44% in 2010), coal 22% (21% in 2010), nuclear 9% (12% in 2010), and hydro and others 7% (5% in 2010).

Power-generation outlook

Japan's improved industrial activities and extremely hot and prolonged 2010 summer, which raised air conditioning demand significantly for July-September, contributed to a 6.6% increase in total power generation last year.

Power generation by natural gas increased by 8.6% y-o-y to 296 Tw-hr; furthermore, generation by coal, oil, and hydro increased by 6%, 1%, and 13.6%, respectively, from 2009. Nuclear power generation (the key baseload power generation) increased by 7% y-o-y to 278 Tw-hr. The average nuclear operating rate in 2010 was 68.4% vs. 64.7% in 2009—the highest level since 2007 when Tepco shut down the 8.2-Gw Kashiwazaki-Kariwa nuclear power plant in Niigata Prefecture after the Chuetsu offshore earthquake.

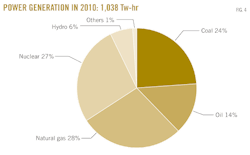

Fig. 4 shows the share of natural gas in total power generation in 2010 (1,038 Tw-hr).

Japan's total power generation in 2011 will likely decline by at least 5% y-o-y, as a result of a supply shortage and nationwide power-conservation efforts.

For mid-March to May, Tepco (Japan's largest electric utility supplying electricity to the Kanto region, which includes the Tokyo metropolitan area) had a program of rolling power blackouts (2-3 hr/day) in its supply areas. For the summer peak season (July-September), the government is instructing consumers to cut electricity consumption in order to reduce the peak demand. Tepco planned to supply 55 Gw by the end of July and 56 Gw by the end of August; a typical summer peak demand is around 55 Gw, and an unusually hot summer (such as that experienced in 2010) requires 60 Gw.

Energy-conservation efforts will be adopted not only in Tokyo but also in other major consumption areas such as Nagoya, Osaka, and Kyushu. With the Hamaoka closure and other nuclear-related issues, Chubu Electric, Kansai Electric, and Kyushu Electric will have limited surplus generation capacities for this summer. Already, many factories are cutting back the need for power during peak hours by moving to night shifts, adopting summer hours, and giving employees long summer vacations. We believe that the electricity savings efforts will become a long-term feature of the country's energy industry, especially as the Kan administration plans to include energy conservation as one of the four key elements of the revised energy policy.

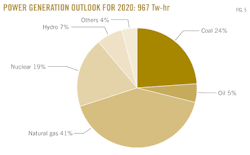

By 2020, we forecast the share of natural gas will increase to 41%; the anticipated increase will come at the expense of nuclear, as the share of nuclear in the power generation mix will likely fall to 19% by 2020 (Fig. 5).

In order to avoid such issues as those Tepco is facing in Fukushima, Japanese electric utilities will increase their earthquake and tsunami-protection measures. This will require temporary plant closures and extended plant maintenance cycles. With stricter maintenance regulations after the Fukushima disasters, utilities would be unable to bring them back on, following a 90-day maintenance cycle, until plant safety is approved by local authorities and the community. Even if units may be brought back in operation, maintenance will take longer than 90 days, thus Japan's nuclear utilization will decline further.

Furthermore, the life span of the existing nuclear reactors will likely be shorter, considering some units in Japan are already 40 years old (Table 5). Every 10 years, utilities obtain permission from the Nuclear and Industrial Safety Agency to operate their reactors another 10 years. The life span is not specifically regulated but must be approved by the agency.

Until recently, it was generally understood that reactors could operate for 60 years if being properly maintained. Following the Fukushima disasters, however, there is already strong opposition to continuing to operate older nuclear units. All those issues will contribute to the reduced nuclear share in total power generation.

Gas demand outlook

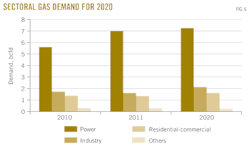

The power sector accounted for 61.9% of Japan's total natural gas demand in 2010 (9 bcfd), a slight increase from 2009, and the city's gas sector (i.e., industrial, residential-commercial, and others) made up the balance. Under the city's gas sector, industrial demand accounted for 19.3% (18% in 2009), residential-commercial demand had a 15.3% share (18% in 2009), and others made up the balance (Fig. 6). Industrial demand notably improved in 2010 from 2009 when demand was hard hit by the economic recession and fell by 13% y-o-y.

Based on current information, we forecast Japan's natural gas consumption in 2011 will increase by 12.8%, to 10.3 bscfd, due to a significant demand increase in the power sector. The power sector's demand will increase by 23.9%, to 7 bcfd, in order to make up for lost nuclear power capacity including Tepco's Fukushima Daiichi and Fukushima Daini, Tohoku Electric's Onagawa, and Chubu Electric's Hamaoka. Furthermore, utilities will not be able to bring back some reactors, currently under maintenance, until plant safety is approved by local authorities following the stress tests.

We forecast that the power sector's demand will peak in 2013, assuming the bulk of nuclear reactors remain closed. After that, gas demand will fluctuate as some of the nuclear units, currently under maintenance or inspection, will eventually return to operation. Our base assumption is, however, that no new nuclear reactors will be built in the next decade.

The share of the power sector in gas demand will increase to 64.9% in 2020 and will start declining thereafter.

The industrial sector's demand will likely fall off this year but increase to higher than the 2010 level in 2013. The following factors will retard city gas sector's demand:

1. Tepco's reduced power supply capacity will affect industrial activities, as well as consumer spending.

2. Damaged infrastructure such as roads, sewage systems, hospitals, and other public offices are slowing the distribution of goods and services.

3. Japanese consumers will restrict spending in sympathy for suffering residents in temporary shelters.

Overall, the industrial sector's demand will grow at an average of 1.2%/year for 2010-15 and at 3.2% for 2015-20. Fig. 6 shows the power sector's overall gas demand will increase at an average of 3.5%/year for 2010-15 and then at 1.7%/year for 2015-20.

In terms of LNG imports, Japan will remain as the world's largest LNG importer by far. All of Japan's natural gas imports are in the form of LNG for the foreseeable future.

In 2010, LNG imports increased by 5.5 million tonnes to 70.0 million tonnes as demand from the power and city gas sectors increased y-o-y.

Consumption by sector, in terms of LNG, is as follows:

1. Power sector at 43.1 million tonnes (+9.4% y-o-y).

2. Industrial sector at 13.1 million tonnes (+11%).

3. Residential/commercial sector at 10.7 million tonnes (+1.9%).

Under our base-case scenario, Japan's LNG imports in 2011 and 2020 will be 78.8 million tonnes and 85.4 million tonnes, respectively.

Energy policy uncertainty

The disaster and its effect on the power sector have changed the Japanese life-style in the most dramatic way and will have profound implications on the global LNG market. It is important to understand, however, that there is a limit as to how much Tokyo will be able to import, considering regional logistics and environmental issues.

On the demand side, energy-saving initiatives by the government and Japanese consumers should be taken very seriously. We certainly believe that Japan's energy-conservation efforts will continue to be adopted nationwide and will remain a long-term feature.

The power sector's future gas demand is inextricably linked with Japan's future energy policy. The Kan administration has pledged to start from a blank slate in rethinking the energy policy following the Fukushima crisis. Local residents and authorities call for higher nuclear safety standards and a better procedure for emergency management, while opposition to building more nuclear power reactors has grown.

On the other hand, for many villages and cities, a combination of employment and government subsidies relating to the nuclear industry plays an important role in their economic activities. Local economies are already being adversely affected, as the plant shutdowns have left many out of work, placing additional pressure on local authorities. Indeed, the nuclear issue is a social as well as an energy security, economic, and political issue. Ultimately, the shape of Japan's postcrisis energy policies will be determined in large by the degree to which local communities accept further nuclear power generation in their vicinities.

There is a dire need for an integrated energy policy grounded in a new post-Fukushima reality. Such an energy policy will require a reassessment of all kinds of renewable energy, including nuclear power, and a review of future energy use. The timing, pace, and scale of any nuclear development, however, will be adversely affected by the Fukushima crisis; thus impacts on the global market, specifically for LNG, will be profoundly felt over the coming years.

The author

More Oil & Gas Journal Current Issue Articles

More Oil & Gas Journal Archives Issue Articles

View Oil and Gas Articles on PennEnergy.com