Eastern Australian coalbed methane supply rivals western offshore conventional resource

Rick Wilkinson

OGJ Correspondent

Dubbed "girlie gas" by skeptics in the early 1990s, Australia's coal seam gas (CSG) sector has risen in the space of 2 decades to be one of the country's major energy resources, particularly in the eastern states.

The numbers are huge. The estimated potential in situ CSG unconventional resource contained in eastern Australia is on the order of 418,000 petajoules or 400 tcf (where 1 petajoule is equivalent to 0.957 bcf). This resource lies primarily in the Surat, Bowen, and Galilee basins of Queensland and the Sydney, Gunnedah, and Clarence-Moreton basins of northern New South Wales.

Admittedly the estimate contains a large amount of guesswork because many areas, such as the Galilee and Gunnedah, have yet to be extensively drilled, but the figure is of similar volume to the estimated conventional gas resource in the Bonaparte, Browse, and Carnarvon basins off Western Australia.

CSG's contributions

Perhaps a more meaningful comparison is to look at the breakdown of the total proved and probable gas reserves (conventional and CSG) established for eastern Australian basins.

Statistics compiled by Grahame Baker of Resource and Land Management Services, Brisbane consultant, indicate that as of the end of 2010, proved and probable gas reserves for Queensland, New South Wales, Victoria, Tasmania, and South Australia total some 44 tcf (Figs. 1-3). Conventional gas, the bulk of which is in the Gippsland basin of Victoria, accounts for about 16.4% of the total. CSG reserves are put at about 83.6% of the total (Fig. 3).

As of June 2010, CSG production in eastern Australia was estimated to be 235 petajoules/year, equivalent to 33% of gas sold into the eastern Australian marketplace. To date about 97% of CSG production is from the Bowen and Surat basins, and 35% of the CSG produced in Queensland is used to fuel power generation.

Indeed, Queensland has been the spur for the sector's recent development dating from the state government's stipulation in 2000 that 13% of all power supplied to the Queensland electricity grid was to come from gas-fired generators by 2005. This was successively increased to 15% by 2010 and then 18% by 2020.

CSG development history

The commercial use of CSG in Australia began in the mid-1990s when Oil Co. of Australia and Tristar developed Peat/Scotia and Fairview fields, respectively, in the Dawson Valley of the southern Bowen basin.

BHP and US Steel were also evaluating CSG in the deep seams at the Moura coal mine west of Gladstone. In the late 1990s Queensland Gas Corp., now a subsidiary of BG, and Arrow Energy, recently bought out by Shell, began work in the Surat basin farther south.

The fledgling CSG industry accelerated in the early 2000s in response to the Queensland government's power generation edict. New company CH4 began investigating the Moranbah coal field region in the northern Bowen basin as a perceived economic rival to the then-proposed Papua New Guinea-Queensland conventional gas project that sought to pipe gas from the Kutubu fields in the PNG highlands across Torres Strait to northeastern Australia.

The coal industry had already progressively drilled some 10,000 holes into the coal seams of the region to determine coal reserves in advance of mining, and the data from these were used to make an initial determination of the region's CSG potential to supply gas for power generation in Townsville.

Exploration also increased in the southern Bowen and overlying Surat basins but kept within corridors about 50 km wide on either side of existing pipelines carrying conventional gas to Gladstone and Brisbane. At that stage the explorer/producers did not want to have stranded gas reserves out of economic reach of infrastructure and markets.

By 2005-06 the industry had met the first Queensland government target and had gained an appreciation of the huge CSG potential. Consumer and financial acceptance of the product had also provided the confidence needed to consider more ambitious plans for expansion and future development. Parallel, albeit smaller, inroads by CSG into the conventional gas supply monopoly also occurred in the Sydney basin of New South Wales.

Supergiant realization dawns

Companies working in Queensland quickly realized that the size of the CSG resource and the planned production growth rate would soon outstrip the domestic demand in that state.

In 2007 they began to investigate other outlets for the gas, including sending it south into New South Wales and west into South Australia. They also looked ambitiously at an even larger scenario: CSG as feedstock to manufacture liquefied natural gas for export.

The companies realized, however, that to fulfill this ambition would require a quantum leap in proved CSG reserves as well as a major increase in production capacity along with a much more extensive delivery system. Consequently in the last few years there has been an explosion of activity as explorers move farther away from the original pipeline corridors to evaluate the outer reaches of the Bowen and Surat basins.

Even more recently, CSG's success has prompted a second generation of activity as new explorers travel to lesser-known coal-bearing basins such as the Galilee in central Queensland, the Gunnedah, and the Clarence-Moreton in northern New South Wales.

To a lesser extent there has also been CSG exploration in the Perth basin of Western Australia and the Arckaringa basin of South Australia, although most of the alternative gas search in both those states has centered on shale gas potential.

Reservoirs and production

Experience in the CSG programs in Queensland and New South Wales indicates that individual well depths are between 350 m and 1,400 m targeting coal seams 3-10 m thick with a net coal thickness within the coal measures of 8-80 m. Gas content can vary between 3 cu m/tonne and 20 cu m/tonne of coal dry and ash free.

Gas permeabilities range from 1 md to 500 md (in contrast to permeabilities for shale gas formations which are measured in microdarcies), while production well spacing is generally between 500 m and 1,000 m.

Average productivity for individual wells is 0.6 terajoules a day, thus a typical five spot production unit will produce about 1 petajoule/year of gas. Estimated well life is 12-15 years with the latter figure taking into account that some downhole workover servicing will be applied.

CSG as a supply for LNG

The move to production of LNG from CSG resources ups the ante on several fronts.

LNG plants will require the supply of about 65 petajoules of raw CSG for each 1 million tonnes of LNG exported.

Breaking that down further, of the 65 petajoules, about 5 petajoules is required to recover, process, and compress gas for transport to the LNG plant. A further 5 petajoules is needed to operate the LNG train. The remaining 55 petajoules is the energy content of 1 million tonnes of LNG. Thus production of around 10 million tonnes/year (tpy) of LNG from CSG will mean a virtual doubling of the current eastern Australian gas demand.

In fact, the four major CSG-LNG projects with LNG plants proposed for Gladstone (BG Group, Santos/Petronas/Total/Kogas, Origin/ConocoPhillips, and Shell/PetroChina) anticipate a total initial output of around 16 million tpy and a staggering ultimate total output of 57-58 million tpy. This will require a raw gas supply of about 3,600 petajoules/year and more than 27,125 production wells.

The BG and Santos-led projects have already been given the final investment go-ahead for the initial trains to come on stream in 2014-15. Origin/ConocoPhillips has received government environmental approval and is aiming at a final investment decision (FID) this year. Shell/PetroChina hopes to apply for government environmental approvals later this year with FID in 2012.

Many thousands of CSG wells

The three project operators with green lights are now out in the Surat/Bowen basins actively following a program of drilling about 1,000 wells/year each. These are a mix of exploration, appraisal, and production.

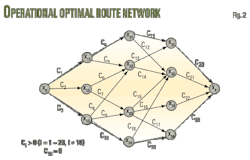

The management strategy calls for the drilling of production wells at the center of areas of known proved reserves and gradually radiating out from those points with step-outs to extend the fields and progressively add more proved reserves to the total.

At the moment the four main LNG project proponents control 86% of the current known proved and probable CSG reserves which, according to Baker, are currently sufficient to support five 4 million tpy LNG processing trains. Each project has sufficient proved and probable gas to support a single 4 million tpy liquefaction train. All of them have sufficient proved and probable or proved, probable, and possible reserves added to contingent resources to supply a two-train plant.

Baker says that provision of feedstock for a two-train LNG plant operating for 20 years will require between 5,000 and 6,000 producing wells which, at 1,000-m spacing, will take up a lot of territory. A part of the land in question in the Surat and Bowen basins is agricultural property, but the bulk is beef country where disruption is less of an issue.

This intrusion into land holdings will be mitigated by the increasing technological ability to drill radiating directional (horizontal) wells into the coal seams from a central location in a spoked, wagon-wheel pattern. In addition, there is already dialogue between the companies and the landholders in question to minimize potential problems with careful planning, such as siting wells along fence lines and within the turning circles of mechanized farm equipment.

Most of the rigs being brought in to cope with the steep increase in drilling, including many from the US, have top drives that can drill a well to 800 m in 3-4 days. They can also drill directional wells from the same location, so the producers are confident they will have sufficient wells to meet the gas supply demands when the first LNG trains are brought on stream in 2014.

The operators have formulated a management strategy of beginning their drilling programs in a central area so they dewater the coals there and gradually move outwards. Once an area is dewatered, the gas flow can be turned on and off without problems—the idea being to rotate well production so that individual wells don't silt up while waiting for the spike in production the LNG plants will require in 3 years' time.

Surplus gas stored underground

In the meantime the gas being produced surplus to immediate requirements of the Queensland domestic market is being sent to storage in depleted conventional gas reservoirs like Silver Springs in the Surat basin.

Eighteen months ago operators also reversed the flow of gas along the Moomba-Roma trunkline so that CSG now flows west into the Moomba hub in South Australia. A number of conventional fields around Moomba (and Ballera in western Queensland) have been shut in and, instead, CSG is used to help satisfy the South Australian and Sydney market demand.

Once the LNG plants in Gladstone come on stream, the connection from the Bowen and Surat CSG fields will be switched back to a west-east flow.

Handling produced water

The spike in drilling has exacerbated the main problem associated with CSG production, and that is what to do with the increase in the volume of water produced when dewatering the coals.

Baker estimates there will be a flow of 150 megaliters/year, although as dewatering runs its course this figure will diminish to 50 megaliters/year in 5 years.

Nevertheless water handling is a major issue for the CSG industry, especially since the Queensland government announced in 2008 that from the beginning of 2012 evaporation ponds as a method of water handling would no longer be approved. The government is concerned that evaporation ponds set up potential long-term environmental problems like ecological damage, groundwater contamination, salt disposal, and landscape impacts.

The alternative options vary depending on the salinity and other chemical components of the produced water as well as its ultimate use. Changing the water chemistry involves reverse osmosis (RO) and the use of gypsum on the soil to counter any sodium absorption. The RO treated water can be put into creek and river systems and used to drought-proof towns in the future as well as for irrigation, livestock consumption, and industrial use.

RO does leave a small volume of by-product hypersaline water, and there is potential for the establishment of a secondary industry in the form of a salt processing plant located somewhere central to the Queensland CSG fields.

Other alternatives for production water where chemical treatment is not needed include reinjection into underground aquifers if the water is compatible with that already in the aquifer, coal washing, and as cooling water in power stations.

The producing companies are looking at these various options, working with local authorities in their areas, and keeping an eye on the evolution of government regulations. Their project environmental approvals are subject to a range of environmental and safety conditions along with the requirement for detailed reporting regimes.

Multidisciplinary government monitoring

For its part, the Queensland government in February 2011 established a multidisciplinary unit tasked with the job of monitoring the emerging CSG-LNG projects.

The unit includes environmental and groundwater experts who will monitor groundwater quality and pressures across the Surat/Bowen region. They will be in addition to petroleum and gas safety inspectors to ensure the industry operates safely for its workers and the community.

The advent of the LNG projects has already led to a huge increase in the work for service companies and the need for skilled construction tradespeople and building and engineering professionals to oversee the massive infrastructure development.

Examples of this include:

• Major well service company Schlumberger recently opened offices in Brisbane to keep up with operational demands.

• Toowoomba-based drilling, well service, and construction company Easternwell was acquired by international major Transfield Services in December 2010 and is now hard at work building new rigs and importing units to cope with the increased demand.

• Pipeline engineering company OSD Pipelines has merged with engineering industrial design firm GWB Engineering to meet the expanding needs of the Queensland CSG program.

The published pricetags for the major projects of between $15 billion and $35 billion include components for field drilling, gathering and production systems, and trunk lines to Gladstone as well as the LNG plant construction and ancillary storage and port loadout facilities.

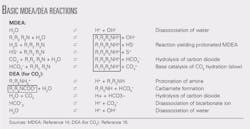

A mitigating factor is that CSG is very low in carbon dioxide compared with most conventional gas-fed LNG projects. Hence the capital and operational costs associated with CO2 removal, capture, and sequestration are much reduced. There may also be a consolidation of some aspects of the four major LNG projects (such as pipelines and plant service infrastructure) aimed at synergies and potential costs savings.

Emerging CSG-LNG projects

The major LNG proponents are not the only players in the CSG game.

Two other companies (LNG Ltd. and Energy World Corp.) plan to build LNG plants in Gladstone, although they are yet to secure feedstock.

There is also talk of constructing an LNG plant in Newcastle, NSW, based on CSG feedstock from the Gunnedah and Clarence-Moreton basins.

In addition, a number of smaller explorers with acreage in Queensland and New South Wales are working to convert their contingent gas resources into proved reserves. Some of this gas will be fed into local power generation projects as well as into the domestic grid, and some may find its way into the future plans of the LNG projects.

As Baker points out, the explosion of activity is largely because the LNG market will potentially provide CSG producers with exposure to large-volume international markets where gas attracts prices well in excess of those that have traditionally prevailed in eastern Australia.

Whatever the final configuration, the burgeoning CSG industry will undoubtedly prompt a major restructuring of the natural gas production and distribution framework in Australia's eastern states.

More Oil & Gas Journal Current Issue Articles

More Oil & Gas Journal Archives Issue Articles

View Oil and Gas Articles on PennEnergy.com