Jude Clemente

Homeland Security Department

San Diego State University

The important role of natural gas as the bridge fuel to a low-carbon economy and more-sustainable energy system raises concern about security of LNG delivery infrastructure. Although forecasts of LNG gas imports have shrunk with the surge in production from unconventional reservoirs, LNG will remain an important link in the transportation chain as consumption of gas grows.

Natural gas emits half as much carbon dioxide as coal and is the preferred backup generation source required for wind and solar energy. In fact, some policymakers are calling for natural gas to supplant coal-fired power generation, which represents half of all US electricity. In a 2010 study, The Future of Natural Gas, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) found that federal policies aimed at cutting greenhouse gas emissions to 50% below 2005 levels by 2050 (the Obama administration's goal is to cut them by 83%) would extend US reliance on gas-fired electricity from 20% to 40%.1 When coupled with the push for more natural gas vehicles to reduce risky dependence on foreign oil, US gas consumption is likely to soar.

The conventional supply basins of North America, however, are rapidly maturing, and production from these areas, having peaked around 2001, is projected to decline by a third over the next decade. Thus, incremental demand growth will need to be met by huge unconventional resources developed by modern drilling and completion technologies. MIT figures that at a "moderate cost base…at or below $5/MMbtu," the US has 1,000 tcf of shale gas available—more than four times the current conventional gas level.2 But several sources have indicated that, as an unconventional resource, above-ground factors designate the outcome of these plays as promising but ultimately indeterminate:

• "The true potential of the US shale gas resource remains uncertain"—US Energy Information Administration (EIA), 2010.3

• "Although production of [shale] gas has expanded…in North America over the last several years…exploitation will face several barriers"—International Energy Agency, 2009.4

• "We need a better understanding of unconventional resources like shale"—Anthony Meggs, MIT, cochair of The Future of Natural Gas, 2010.

Default source

Any shortfall in the US unconventional gas supply would make LNG the default source of natural gas in a world where 60% of the global endowment is controlled by Russia, Iran, Qatar, and Venezuela. Indeed, the security of LNG was a hot topic in the years following the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, when it appeared as if imports would jump. Unfortunately, this subject must now be revisited because the shale plays, along with the rare chance to enhance US energy security, could be hampered by political constraints as quickly as they arrived.

For example, Stephen Comstock, tax policy manager at the American Petroleum Institute, says proposed new taxes on shale gas development make "no sense" and would "hurt the 2.1 million people directly employed by the oil and natural gas industry."5 The industry reports the possible federal regulation of hydraulic fracturing fluids used to complete wells in shales would cost $150,000/well and force 35% of the gas wells in the US to close.6 Sara Banaszak, a senior economist at API, notes as many as 80% of the gas wells drilled in the US over the next decade will utilize hydraulic fracturing.7 In September, Wyoming became the first state to require public disclosure of the chemicals used in shale production.

LNG hazards

The hazards of LNG, which is odorless, colorless, nontoxic, and noncorrosive, include flammability, freezing, and asphyxia.

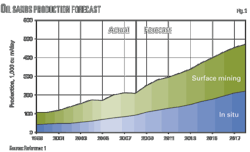

After a record high of 771 bcf in 2007, the US imported 450 bcf of LNG in 2009, 90% of which came from Trinidad and Egypt.8 By comparison, total domestic gas demand in 2009 was approximately 23,000 bcf. The EIA's Annual Energy Outlook 2010 projects LNG imports will increase to a peak of 1,500 bcf in 2020 and then steadily decline to 830 bcf in 2035. Yet the potential for policy limitations on the shale gas industry, not to mention new offshore production obstacles due to the Deepwater Horizon spill, could have LNG playing a larger role than otherwise would be necessary. Fig. 1 illustrates the four main possibilities.

The threat

Al-Qaeda and its ilk realize the US energy supply system is more exposed when forced to extend out. Osama bin Laden's "bleed-until-bankruptcy" asymmetrical warfare plan centers on employing a "holy war" to attack the global infrastructure that supplies the US. For example, in February 2007, Sawt al-Jihad, the online magazine of Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula, called on Muslims to cut US supply lines to "contribute to the ending of the American occupation of Iraq and Afghanistan."9 Importantly, the terrorism strategy so far has mostly focused on oil facilities, but natural gas infrastructure would become an increasingly attractive target if the US deepened its reliance on foreign gas for electricity.

The Middle East is the hub of global terrorism, but the region easily retains the world's greatest potential for LNG growth. According to BP's Statistical Review of World Energy, June 2010, the Middle East controls 41% of the world's conventional natural gas reserves (North America and Europe hold just 6% combined), and full development hinges specifically on adding LNG capacity.10 Middle East exports, meanwhile, sit directly in the line of fire, as US-bound tankers leaving the region must pass through the most dangerous waters in the world (Fig. 2). Indeed, the expanding LNG trade and the emerging global gas market are riddled with terrorist threats:

• The world's top four LNG exporters—Qatar, Indonesia, Malaysia, and Algeria—are officially Muslim nations and as such have been ordered by Al-Qaeda to attack American interests in all ways possible.

• Iran is the largest state sponsor of terrorism in the world and holds the second largest gas reserves at 1,045 tcf—over four times those of the US.

• Russia, the nation with the most gas reserves (1,565 tcf), has long struggled violently against Islamic separatists in its Chechnya republic who favor the targeting of energy infrastructure.

Vulnerable infrastructure

LNG infrastructure offers terrorists low-cost, high-impact value and was recently proven vulnerable: Al-Qaeda took credit for bombing a pipeline operated by Yemen LNG in September. Husick and Gale (2005) indicate that "with real-time information on the position, heading, speed, and destination of an LNG tanker, together with similar information for most of the other vessels in the port, execution of a [USS] Cole-style attack would be a relatively simple exercise."11 LNG tankers carry very hazardous and potentially explosive material and are typically longer than three football fields. In 2004, Sandia National Laboratories (SNL) outlined the ways terrorists could target an LNG tanker and the possible impacts:12

• Ramming could occur between an LNG tanker and a fixed object or between the tanker and another vessel. SNL confirms that a breach in the hull is unlikely, but such a break would cause methane to escape as a vapor and mix with air in concentrations with potential to ignite.

• Triggered explosives, such as mines, could be placed in the path of an LNG tanker or on the vessel itself. If powerful enough, the explosion could cause the cargo to spill dangerously.

• External attacks were used against the USS Cole in 2000, when suicide terrorists detonated explosives after pulling up alongside the warship in a small boat. Other methods to attack an LNG tanker include missiles, rocket-propelled grenades, and air strikes. The massive explosion in the Cole bombing killed 17 people.

• Hijacking is potentially the most catastrophic scenario under an LNG attack. Here, terrorists commandeer an LNG tanker, sail it toward a population center, and attempt to detonate the cargo.

LNG hazards need to be kept in perspective. Portrayals of LNG carriers as floating bombs are exaggerated. The explosive threat from LNG is mostly the possibility for rapid phase transition when the cryogenic liquid spills onto water. The more likely hazard is ignition of escaped methane before the gas dissipates beyond its flammable concentration in air. Explosive combustion can occur only when methane collects in a confined space, a phenomenon very unlikely to occur around an LNG vessel.

The only notable LNG incident in the US occurred in Cleveland, Ohio, in 1944, when a storage tank burst and nearly 130 people were killed. Although cold-storage technology has made great strides since the accident, attacks on LNG facilities are "not a difficult thing to do if you're determined to do it," says James Fay, a security expert at MIT.13 In 2004, a study commissioned by the Boston Fire Department estimated that up to 10,000 people could die in an LNG fire in Boston, Mass.14 A report released by Good Harbor Consulting, a private Homeland Security firm, in 2005 concluded that a successful strike against an LNG tanker in Providence, RI, could result in as many as 8,000 deaths and upwards of 20,000 injuries.13

Security mechanisms

According to the University of Texas' Center of Energy Economics (CEE), several US agencies are involved in the protection of the LNG industry. The Coast Guard is responsible for assuring the safety of all marine operations at LNG terminals and on tankers in US coastal waters. The Department of Transportation regulates LNG tanker operations. And the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission is responsible for permitting new onshore LNG regasification terminals and ensuring safety at these facilities through various forms of oversight.15

The US has the largest number of active LNG facilities in the world with 113. These facilities are spread across the country, with a high concentration in the more densely populated Northeast. FERC reports there are nine LNG import terminals in the Lower 48, up from four in 2003.16

In 2004, new maritime antiterrorist regulations went into effect that directly impact LNG terminals. All vessels and ports worldwide that engage in international trade must comply with the International Ship and Port Security code. Foreign-flagged vessels entering US waterways must meet the security requirements of the Maritime Transportation Security Act of 2002. According to FERC, all LNG tankers entering US waters must:17

• Certify security plans that address how they would respond to emergency incidents.

• Identify the person authorized to implement security actions.

• Describe provisions for establishing and maintaining physical security, cargo security, and personnel security.

These plans must be updated at least every 5 years and be reapproved if a change is made to the tanker that could affect its security. Tankers must be equipped with automatic identification systems that allow vessel tracking and monitoring while navigating on US waters. And the Coast Guard can assign sea marshals to accompany tankers as they transit US ports to ensure harbor security.

The CEE reports there are four requirements for LNG protection that apply across the LNG value chain, from production to liquefaction and shipping to storage and regasification. In addition to standards and regulatory compliance, these layers have helped maintain the industry's exemplary, decades-long safety record:

1. Primary containment involves the use of "appropriate materials for LNG facilities as well as proper engineering design of storage tanks onshore and on LNG ships and elsewhere."

2. Secondary containment uses dikes, berms, and double and full containment systems to keep LNG leaks or spills contained and isolated from the public.

3. Safeguard systems minimize the frequency and size of LNG releases to prevent harm from fire hazards. The industry relies on high-level alarms and emergency shutdown systems.

4. Separation distances and safety zones are required by regulation to separate LNG facilities from local communities and other public areas.

Research stemming from the 1944 Cleveland LNG accident influenced many of the industry standards used today. For example, stainless steel was scarce during World War II, so the cylindrical tank was made from another alloy—3.5% nickel steel. The tank was placed in service and eventually failed catastrophically upon contact with cryogenic LNG. The 3.5% nickel steel is no longer used for cryogenic applications and has been replaced by 9% nickel steel, which does not embrittle at low temperatures. According to Saraf (2006), the Cleveland incident made it "evident that LNG storage tanks needed to be provided with full capacity diking and that tanks should be spaced to prevent failure from exposure to nearby fire."18

Advancing technologies

Steve Kirchhoff, ExxonMobil's vice-president for natural gas, says unconventional sources of natural gas could represent up to 70% of US supplies in 2030.19 Self-imposed restraints on domestic production, however, would have the US importing more LNG from the far-off, less-secure regions that dominate supply of conventional gas; North American sources cannot provide the insulation that they do for oil.

Globally, the LNG trade must constantly deploy advancing technologies and practices as gas markets become more integrated and security threats proliferate. For the US, if the established standards and protocols are maintained with regulatory supervision, LNG should continue to be transported, stored, and consumed safely and securely.

As of November 2010, FERC reports there were five proposed US LNG import terminals that would add total capacity of 6.5 bcfd. While environmental issues have been the purported reasoning behind recent arguments against new LNG facilities, terrorism does remain a concern. An editorial in The Boston Globe on Nov. 10, 2010, for instance, cited security in its position against Weaver's Cove Energy's (a subsidiary of Hess) LNG import project.20 The formation of more infrastructure demands that Congress meet the LNG-terrorism challenge head-on by directly assuaging public fears.

References

1. MIT Energy Initiative, The Future of Natural Gas, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, http://web.mit.edu/mitei/, 2010.

2. Meggs, Tony, Natural Gas Supply, MIT Energy Initiative, http://www.rug.nl/energyconvention/edc/archive/edc2009/presentations/meggs2.pdf, Nov. 17, 2008.

3. Energy Information Administration, Annual Energy Outlook, US Department of Energy, May 11, 2010.

4. International Energy Agency, World Energy Outlook 2009, Paris, November 2009.

5. Comstock, Stephen, Who Will Be Hurt By Higher Taxes on Energy Companies, American Petroleum Institute, http://www.energytomorrow.org/energy_taxes.aspx, n.d.

6. Kenworthy, Tom, Frack Attack: Drilling Technique Under Scrutiny, Center for American Progress, http://www.americanprogress.org/issues/2009/06/frack_attack.html, June 25, 2009.

7. Dlouhy, Jennifer, Energy companies oppose tougher regs on gas drilling, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, http://www.post-gazette.com/pg/10323/1104499-84.stm, Nov. 18, 2010.

8. Energy Information Administration, US Natural Gas Imports by Country, US Department of Energy, http://www.eia.doe.gov/dnav/ng/ng_move_impc_s1_a.htm, Oct. 29, 2010.

9. MSNBC, Venezuela bolsters oil security after threat, http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/17149034/ns/world_news-terrorism, Feb. 15, 2007.

10. BP, Statistical Review of World Energy June 2010, London, UK, 2010.

11. Husick, Lawrence, and Gale, Stephen, Planning a Sea-borne Terrorist Attack, Foreign Policy Research Institute, Philadelphia, Mar. 21, 2005.

12. Sandia National Laboratories, Guidance on Risk Analysis and Safety Implications of a Large Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) Spill Over Water, US Department of Energy, http://www.fossil.energy.gov/programs/oilgas/storage/lng/sandia_lng_1204.pdf, December 2004.

13. Kaplan, Eben, Liquefied Natural Gas: A Potential Terrorist Target?, Council on Foreign Relations, http://www.cfr.org/publication/9810/liquefied_natural_gas.html, Feb. 27, 2006.

14. Abel, David, and Guilfoil, John, Security high as Yemini LNG arrives, The Boston Globe, http://www.boston.com/news/local/massachusetts/articles/2010/02/24/security_high_as_yemeni_lng_arrives/?page=full, Feb. 24, 2010.

15. Center For Energy Economics, Is LNG a Safe Fuel, University of Texas, http://www.beg.utexas.edu/energyecon/lng/LNG_introduction_10.php, n.d.

16. Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, North American LNG Terminals Existing, Washington, DC, http://www.ferc.gov/industries/gas/indus-act/lng/LNG-existing.pdf, Nov. 8, 2010.

17. Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, Maritime Security Regulations, Washington, DC, http://www.ferc.gov/industries/gas/indus-act/lng/marit-secur-regs.asp, June 28, 2010.

18. Saraf, Sanjeev, 1944 Cleveland LNG Incident: Lessons Learnt, Risk and Safety Blog, http://risk-safety.com/cleveland-1944-lng-incident-lessons-learnt/, Apr. 12, 2009.

19. Ordonez, Isabel, Exxon Exec: Unconventional Gas To Be About 70% Of US Supply in '30, The Wall Street Journal, http://online.wsj.com/article_email/BT-CO-20101118-713506-kIyVDAtMUMwTzEtOTIxMDkxWj.html, Nov. 18, 2010.

20. The Boston Globe, In Fall River, gas-storage tanks pose too great a risk, http://www.boston.com/bostonglobe/editorial_opinion/editorials/articles/2010/11/10/in_fall_river_gas_storage_tanks_pose_too_great_a_risk/, Nov. 10, 2010.

The author

More Oil & Gas Journal Current Issue Articles

More Oil & Gas Journal Archives Issue Articles

View Oil and Gas Articles on PennEnergy.com