EU REFINING-1: Needs to meet distillate demand, export gasoline squeeze refiners

On Nov. 17, 2010, the European Commission adopted a "Communication 'Energy infrastructure priorities for 2020 and beyond-A Blueprint for an integrated European energy network.'" In the document, the commission defines EU "priority corridors" for the transportation of electricity, gas, and oil (OGJ Online, Nov. 18, 2010).

A background document released at the same time-"Commission Staff Working Paper: On Refining and the Supply of Petroleum Products in the EU"-presents an overview and analysis of problems facing European refiners.

This is the first of three articles that present the elements of that working paper. This article examines demand issues as they have and will affect European refining. The second article (Feb. 7, 2011) will present the working paper's views on supply issues and the economic viability of the European refining industry. The final article (Mar. 7, 2011) will present the effects of future demand developments on European refining by 2030.

Background

In November 2008, the European Commission announced in the Second Strategic Energy Review (SER2) that a Communication on Refining Capacity and EU Oil Demand would be prepared in 2010.

SER 2 focused on energy security and-given the EU's dependence on oil imports and on exports and imports of petroleum products-highlighted both the need to improve transparency in the demand-supply balance for refining capacity and concerns over the potential availability of diesel fuel in the future.

Since November 2008, concern has shifted from security of supply to how the EU refining industry's adaptation to a changing business environment is likely to affect the EU and how EU policies to decrease the its dependence on fossil fuels will further add pressure on the EU refining sector. These developments prompted the decision for a factual study, in the form of a Staff Working Document, instead of the Communication announced in SER2.

As already noted, the resulting study accompanies the Communication on energy infrastructure priorities for 2020 and 2030 that emphasizes the continued contribution of oil to EU's energy mix and to transportation up to 2030. It also notes that the future shape of crude oil and petroleum product transport infrastructure will also be determined by developments in European refining.

In that context, the focus of the working paper is to illuminate refining activity and the supply of petroleum products in the EU and to highlight and explain key current and future problems facing EU refining. It is also to report some initial quantification of a number of those problems in terms of the effects by 2030 of PRIMES EU petroleum product demand projections.1

And finally, the working paper contains a detailed, factual account of the characteristics of the EU refining industry and some comparisons with other parts of the world in order to provide the necessary background and context.

EU refining, product supply

Here are some key facts about EU refining and trade in petroleum products:

- In May 2010 there were 104 refineries operating in the EU. The EU's crude refining capacity in 2010 represented 778 million tonnes/year (or 15.5 million b/d), equivalent to 18% of total global capacity.

- The EU is the second largest producer of petroleum products in the world after the US.

- There are refineries in 21 member states, with the exceptions of Cyprus, Estonia, Latvia, Luxembourg, Malta, and Slovenia.

- The global financial and economic crisis that began in 2008 has affected margins in all regions of the world. If average annual margins are compared, however, North West Europe has fared better than other regions in the last 3 years.

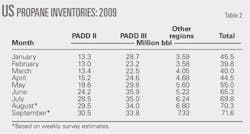

- In 2009, the average utilization rate-crude throughput as a portion of operable refining capacity-among European countries in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development amounted to 79%, compared with 85% in 2008. By November 2010, utilization rates were averaging 76%, showing a continuing downward trend. This needs to be put in the context of previous utilization rates for the EU of close to 90% as recently as 2005.

- When the evolution of the petroleum product demand mix in the EU is examined, the share of jet fuel and kerosine increased between 1990 and 2008 to 9.4% from 5.5%; the share of gas oil (including diesel but not heating oil) to 31% from 17.7%. The share of gasoline fell to 16.1% from 22.7%; the share of heavy fuel oil to 6.4% from 16.3%.

- The two key trade petroleum products in the EU in terms of volume have been gasoline and gas oil-diesel (include heating oil), gas oil-diesel being the main petroleum product imported into the EU while gasoline is the main product exported from the EU. The EU is also very import-dependent on jet fuel and kerosine.

- Russia is the largest supplier of gas oil-diesel to the EU, followed by the US, while the US is the largest importer of gasoline from the EU. In the case of kerosine-jet fuels imports, the third largest traded product, the EU mainly relies on several Middle Eastern countries.

Evolution of demand

It is widely considered that the EU petroleum product market is a mature market that has more than likely already peaked. Between 1990 and 2008, EU demand for petroleum products grew by an average of only 0.2%/year, recording its highest level in 2005 after which it fell every year, registering a 3% fall 2005-08 (Fig. 1).

Analyzing the progression of demand in individual petroleum products reveals very different trends. Between 1990 and 2008:

- Jet fuel and kerosine consumption almost doubled.

- Consumption in gas oil (i.e., transport diesel) registered a steady and sustained growth.

- Demand for naphtha registered an initial increase and then fell.

- Demand for gasoline and heating oil fell quite sharply, while demand for heavy fuel oil fell significantly.

Projecting towards the short-to-medium term, what is relatively certain is that the fall in heavy fuel oil will continue, given the gradual eradication of the use of such products due to regulation on the specification of petroleum fuels towards cleaner, less polluting fuels.

With regard to the evolution of middle distillates, it is expected that heating oil should continue to fall as more efficient and environmentally friendly district heating systems continue to replace traditional oil burners.

Gas oil evolution will depend on a number of variables, such as:

- Whether EU support to promote the wider use of non-fossil fuels is successful.

- Whether tighter marine fuel specifications will lead to a broad switch from residual fuel to marine gas oil rather than desulfurized residual oil.

- And, to a lesser extent, whether the EU-wide tax differential between road diesel and gasoline2 is maintained.3 Kerosine-jet fuel demand, however, will continue to grow until arrival of large-scale use of suitable renewable fuels in airplanes.

Equally, the direction of growth in the demand for light distillates (LPG, gasoline, and naphtha) will depend on several considerations. In particular, development of demand for gasoline will depend on the growth and success of alternative-fuel vehicles and energy taxation (as for gas oil), as well as developments in the penetration of sustainable, renewable fuels in the US (discussed presently) and gasoline-engine efficiency.

Other than economic developments, the two factors most likely to affect future demand for petroleum products in the EU are the forthcoming revision of the Sulphur Content in Liquid Fuels Directive to integrate tighter international regulations on the sulfur content of marine fuel4 as well as recent legislation to reduce CO2 emissions from new cars and transport fuels.5

The requirement to supply future marine fuel with a maximum sulfur content of 0.1% in the Baltic Sea and the North Sea and English Channel could amount to an increase in demand for middle distillates of around 15 million tpy from 2015 (which represents close to 8% of EU gas oil demand in 2008).

This very much depends on how the new changes are dealt with. There is the possibility that ships will widely opt to continue using high-sulfur fuel oil after having installed on-board scrubbers to remove the sulfur.

Notwithstanding the fact that shipowners switching to gas oil will likely have to pay more for their fuel than if they continued to use fuel oil, a key advantage for ships from scrubbing is that it would allow them to meet sulfur-cap requirements wherever the ship trades.

There is, however, some skepticism on this option, given that many ships have held back from making the necessary investments to prepare for compliance with the existing EU requirement in the sulfur-content directive of the use of marine fuels by ships on inland waterways and at berth in any EU ports containing no more than 0.1% of sulfur by January 2010.

(This led to a recommendation by the Commission to Member States to request from ships that have failed compliance by that date detailed evidence of the steps they are taking to ensure compliance, including a contract with a manufacturer and an approved retrofit plan to be completed no later than Sept. 1, 2010.)

While sulfur fuel specifications could represent a source of increasing demand for (marine) transport fuel from EU refiners, it is expected that CO2 emissions legislation will contribute to improved efficiency of vehicles such as through increased penetration of hybrid vehicles, thereby reducing demand for such transport fossil-fuels as gas oil and gasoline. It is expected that this regulation will lead to a penetration of conventional hybrids equivalent to 27% of the total passenger fleet by 2030 (as contained in the PRIMES Reference scenario).

Demand, supply

Two trends have characterized the growth in demand for petroleum products in the EU since 1990: the continued, strong growth in middle distillates such as jet fuel and kerosine and gas oil on the one hand; and the parallel strong declines in demand for gasoline on the other.

Between 1990 and 2008, demand for middle distillates (including heating oil) grew by 35% (and demand for jet fuel-kerosine and diesel increased by 82%), while demand for gasoline fell during that same period by 26%. In parallel, EU supply of middle distillates 1990-2008 grew by 28%, while gasoline supply only fell by 4%.These developments resulted in a supply-demand imbalance in the EU with regard to such products, which has led it to depend on trade in order to balance demand and supply (Fig. 2).

By 2008, gas oil-diesel (including heating oil) was the main petroleum product imported into the EU, reaching 20 million tonnes of net imports, equivalent to 6.9% of EU gas oil-diesel consumption. In contrast, the main product exported from the EU was gasoline, with net exports of 43 million tonnes in 2008, equivalent to 31% of EU gasoline production.

Regarding gas oil-diesel imports, Russia is by far the largest supplier of the product into the EU, having exported 13.7 million tonnes of gas oil-diesel in 2008 to the EU. Though this amount represents only 4.8% of total EU demand of 288 million tonnes of gas oil-diesel for that year, it amounts to 35% of total gas oil-diesel imports.

Regarding gasoline, the EU exported 18.7 million tonnes of excess gasoline to the US that same year, equivalent to 13.6% of EU gasoline production (of 137 million tonnes) and 37% of total EU gasoline exports in 2008.

If net imports of kerosine and jet fuels are taken into account, the EU shortfall in middle distillates amounts to about 35 million tpy of net imports, imports of kerosine and jet fuel coming mainly from several Middle Eastern countries.

Growing trade deficits

Should EU demand for middle distillates continue to grow (as is generally expected) and should the current structure of EU refining remain unchanged, it will mean processing more crude and obtaining more middle distillates but also more gasoline, thereby leading to a widening of the EU supply-demand imbalance for diesel and gasoline.

So far the US has served as a convenient outlet for excess EU gasoline, but it is widely predicted to reduce its consumption of gasoline in the future. While the US vehicle stock will continue to be dominated by gasoline in the foreseeable future, it is suspected that the demand for it has already peaked as more efficient vehicles are produced and as the proportion of biofuels (mainly ethanol) progressively grows to represent a greater proportion of US vehicle fuel use.6

But should there be other potential markets to which the EU could export its surplus gasoline, keeping the status quo (in terms of refining capacity) could be an option for the industry. The most obvious markets are Africa and the Middle East, as these are the closest to Europe and both to experience growing demand in gasoline. Future gasoline trade deficits in both these regions, however, are likely to be well short of current EU gasoline export levels.

In terms of increasing imports of gas oil-diesel, while Russia has been a reliable source of supply to date, it could prove difficult for it to meet any large increases in EU demand for diesel imports, given that Russian refinery capacity today remains at the same level as in the late 1990's7 and also taking into account relatively modest developments in capacity expected in the near future.

On the other hand, the situation that currently prevails in Russia, in which its refiners process more crude than required by domestic consumption in order to export the excess, will likely remain for the foreseeable future. This situation largely results from the current tax regime, which taxes crude exports more highly than product exports.

Russian oil export tariffs on light oil products are typically 70% of export tariffs on crude oil, and export tariffs on heavy oil products represent only around 40% of crude export tariffs.8 Thus Russia can be expected to continue to run a trade surplus in diesel in the future.

Other countries, such as China, India, or Saudi Arabia, have greatly expanded diesel capacity in recent years and could be relied upon to supply the EU market. This being said, demand for diesel will grow significantly across the globe, with Asia-Pacific in particular foreseen to be running a large diesel deficit, as diesel experiences the fastest growing demand of refined products in the region.

And while North America is currently the second biggest supplier of diesel to the EU, running a surplus in diesel capacity of upwards of 30 million tonnes, it is likely that it will run only a slight diesel surplus from 2015, as it becomes the fastest growing refined product in demand there, reflecting increasing volumes of road freight and some dieselization of the private car fleet.9

In conclusion, should the refining industry opt for the status quo in an environment of growing demand for middle distillates, the EU's import deficit in middle distillates will continue.

This is a problem not only for the EU in terms of growing import dependence for such products, but also for EU refiners in terms of growing pressures on them to export excess gasoline to other markets. This problem is not evident, given expected future developments in world demand for gasoline and diesel.

Notes

1. Editor's note: "The PRIMES Energy System Model," National Technical University of Athens/European Commission Joule-III Programme; http://www.e3mlab.ntua.gr/manuals/PRIMsd.pdf.

2. According to June 2010 figures from the Commission Oil Bulletin, while pre-tax consumer prices of premium unleaded gasoline are lower than for diesel in all but 1 of the EU 27 Member States (Malta), higher taxes and duties on gasoline mean that the price of diesel is cheaper at the pump in 26 of the 27 EU Member States (with the exception of the U.K.).

3. A future revision of the Energy Taxation Directive may address this differential, but even if it proposed changes that would lead to the disappearance of this differential across the EU, it would take a while to have an impact, given 10 to 15-year replacement cycles for cars and given that most diesel is still used by commercial vehicles for which the possibility of switching to gasoline is more limited.

4. The 2008 revised International Maritime Organization MARPOL Annex VI regulation on sulfur restrictions in marine fuels provides for a shift to low-sulfur fuel for maritime transport first within the European Emission Controlled Areas (the current fuel-sulfur limit of marine fuels would be reduced to 1.0% from 1.5% by 2010 and then to 0.1% by 2015) and in a second phase, globally where the maximum permitted sulfur level would be reduced to 3.5% from 4.5% by 2012 and then to 0.5% by 2020 (with an alternative date of 2025 if suitable fuel is not available, to be decided by 2018). The European Emission Controlled Areas are the Baltic Sea and the North Sea and English Channel.

5. Adopted in April 2009 along with the climate and energy package, it requires reductions in the average fuel consumption of new cars, with binding targets of 130 g/km (from 140 g/km) by 2010 and 115 g/km by 2020. The Fuel Quality Directive amended at the same time further tightens fuel specifications and introduces a requirement to lower life cycle greenhouse gas intensity of transport fuels by 6% by 2020.

6. In its Annual Energy Outlook 2009 reference case, the US Energy Information Administration projected drops in the growth of motor gasoline consumption in the US equivalent to -8.4% between 2010 and 2020 and another 5.2% drop between 2020 and 2030 (equivalent to -13.1% between 2010 and 2030). Upcoming emission standards as well as the passing of the 2007 US Energy Independence and Security Act, which promotes use of biogasoline, represent key influences on future US demand for gasoline. In addition, the Obama administration has brought forward a requirement for better vehicle fuel consumption. By 2011, the Corporate Average Fuel Economy requirement on car-manufacturers will shift to an average consumption of 35.5 mpg from 27.3 mpg.

7. According to Russian oil refining capacities contained in the BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2009. Note however that in his report to the State Duma on Dec. 2, 2009, the Russian Energy Minister announced that 1.2-1.4 trillion rubles (€32 billion) would be invested in upgrading refinery capacity in Russia.

8. The Russian Ministry of Economic Development has recently prepared amendments to customs tariffs that provide for more equal export tariffs for light and heavy products.

9. Projections by Wood Mackenzie, as part of its work evaluating the impact of biofuels on the EU refining industry for the European Commission.

More Oil & Gas Journal Current Issue Articles

More Oil & Gas Journal Archives Issue Articles

View Oil and Gas Articles on PennEnergy.com