New decommissioning requirements will lower Gulf of Mexico production

Mark J. Kaiser

Yunke Yu

Center for Energy Studies

Louisiana State University

Baton Rouge

The US Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, Regulation, and Enforcement (BOEMRE), formerly known as the Minerals Management Service, issued new guidelines and measures in the form of Notice to Lessees 2010-G05 on Sept. 15 for decommissioning idle wells and structures on active leases on the Gulf of Mexico Outer Continental Shelf (OCS).

NTL 2010-G05 dissolves the lease boundary in determining decommissioning time lines and redefines the regulatory requirements at the individual wellbore and structure level by specifying the maximum number of years wells and structures are allowed to remain idle before they have to be abandoned. NTL 2010-G05 is a significant departure from historic requirements and, as far as we are aware, is the first regulation across any offshore basin to require infrastructure to be decommissioned after production ceases for a fixed period of time.

The purpose of this article is to quantify the costs of NTL 2010-G05 and the economic consequences of prematurely abandoning idle infrastructure. The value of an idle well is the potential that it may produce again in the future, but because of uncertain and imperfect information operators do not and cannot know the future utility of their idle inventory. If idle wells are prematurely abandoned and idle structures are removed, the opportunity for future production will be lost or greatly diminished.

In the short term, operators will clean up and cut their idle inventory, and within a few years all wells and structures that have not produced for 5 years or more will be plugged and removed. Longer-term, the new regulations impose uncertain consequences for production operations and will impact cost outlays, efficiency, and development opportunities in the region.

We estimate that the gross revenue lost as a result of NTL 2010-G05 will range between $6.2 billion to $18.6 billion. Foregone government royalties are expected to fall between $775 million and $2.3 billion. If the decommissioning time lines for idle wells were reset using a 10-year criteria, lost production is estimated to decrease to $3.5-11.4 billion.

Production intermittency

No well or structure produces continuously throughout its lifetime. Maintenance, workovers, production problems, downstream disruptions, low commodity prices, and hurricane damage impact operations and stop production for various periods of time. In every field development, and on every offshore structure, wells begin and end production at different times; therefore, some wells become idle as other wells continue to produce. Wells that stop producing may be used at a later time to further explore the formation and seek future development opportunities.

When production on a lease ceases, the lease terminates. Historically, federal regulations required that companies permanently abandon all wells and remove all structures on a terminated lease within 1 year. Because a lease often has many wells and one or more structures, wells and structures sit idle on a lease until the lease stops producing. As long as a lease is producing in paying quantities, inactive (idle) wells and structures can be held on the lease and remain in compliance with the lease instrument.

Activity spectrum: wells

Fig. 1a is a snapshot of the producing status of all original wellbores currently in the shallow-water (<500 ft) Gulf of Mexico, with shading indicating production status. A light shade indicates production, and a dark color indicates no production; age is represented along the vertical axis. The production activity of each well is initialized from its time of completion, represented at the bottom of the chart, to the current production status, at the top of the chart. Sampling is on annual basis, and the length of each vertical segment represents the age of the well.

The plot demonstrates that production intermittency is a part of normal field operations. We refer to charts that represent production activity as the "activity spectrum."

Several observations are apparent:

• Almost all wells begin producing immediately after completion (i.e., light colors dominate near the bottom of the graph).

• All wells move into and out of production throughout their lifetimes, meaning that at any point in time, every idle well has a probability of returning to production in the future.

• As wells age, the amount of time a well spends idle increases (i.e., the color generally darkens moving up the graph).

• Old wells are idle more often than new wells (i.e., the color density increases moving from right to left).

• Activity frequency is well-specific and varies with characteristics of the well.

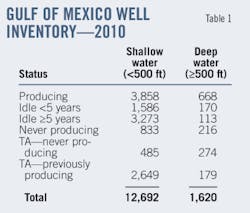

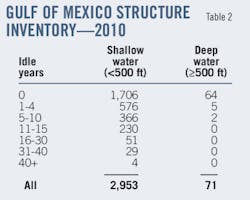

In water depth less than 500 ft, there are currently 3,858 producing wells, 1,586 wells that have not produced within the last 4 years, and 3,273 wells that have not produced for 5 years or more (Table 1). There are also 833 wells that have never produced but have not been permanently abandoned. In water depth greater than 500 ft, the active-well inventory is much smaller—668 producing wells, 170 wells idle less than 5 years, and 113 wells idle for 5 years or more; 216 deepwater wells have never produced but are not classified as permanently abandoned.

The activity spectrum for deepwater wells, shown in Fig. 1b, reveals the same general characteristics as those of shallow-water wells. Because there are fewer active deepwater wells, the spectrum is easier to distinguish, and the age distribution is significantly younger, with about half of all wellbores less than 10 years old. For shallow-water wells, over half of the well inventory is more than 20 years old, and about 10% of wells are greater than 40 years old. Old deepwater wells are inactive more often than young wells, and as wells grow older they are subject to additional down time. These observations are consistent with and analogous to man-made and natural system behavior.

Activity spectrum: structures

Structures process production from one or more wells; therefore, the production profile of a structure is determined via its well inventory. All structures eventually become idle unless additional wells are drilled and brought into production or the function of the structure changes.

The activity spectrum of structures exhibits characteristics similar to those of the activity spectrum of wells since they are simply the aggregate of well activity (Fig. 2). We expect structures to exhibit a higher activity level than individual wells, however, because they are the composite from multiple independent production streams; as long as one well on a structure is producing, the structure is active. The activity spectrum of structures is thus lighter in color than the well spectrums, and this is expected. Deepwater structures are active a greater portion of their lifetime due in large part to the greater number of wells per structure and their lower age.

In water depth less than 500 ft, there are currently 2,953 active structures compared to 71 active structures in deep water. Shallow-water structures host on average 1-8 wells each, depending on structure type (e.g., caissons—1 well, well protectors—2 wells, fixed platforms—8 wells). Deepwater structures host on average 8-27 wells per structure type (e.g., minitension leg platforms and semisubmersibles—8 wells, spars—13 wells, tension leg platforms-18 wells, fixed platforms—19 wells, compliant towers—27 wells). There are currently 1,706 producing structures in shallow water, compared with 64 producing structures in deep water. A total of 680 shallow-water structures have not produced in 5 years or more, compared with two deepwater structures (Table 2).

Uncertain production loss

All idle wells have a chance to return to production, but this opportunity requires the operator to spend capital. Inactive wells do not return to production by happenstance simply by reopening valves or drilling out cement plugs. An inactive well returns to production only if geologic conditions are conducive for production and operators accept the risk that capital to sidetrack and further explore the formation may not yield a positive return on investment.

The probability that an idle well will return to production is small and depends on many, mostly unobservable, factors. The probability an idle well will return to production is non-zero; this small probability of success balanced against possibly high return is a defining characteristic of the exploration and production industry. Regulations that constrain or otherwise limit this characteristic will change the nature of the business model in unforeseen ways and in a negative direction by imposing uncertain and possibly significant impacts on opportunities and the manner decisions are made.

Once a well is permanently abandoned, the chance of generating future revenue from the wellbore is essentially lost. The opportunity to return to production and generate future revenue will be diminished when a fixed schedule for decommissioning is imposed since operators may unknowingly abandon wells with future utility.

Oil and gas exploration and production are unlike other business ventures because of the uncertain, imperfect, and incomplete information that operators must manage throughout the lives of their assets. Regulations need to properly account for the operational realities of the business.

Benefits and costs

In every field development, wells begin and end production at different times; therefore, idle wells accumulate before production ceases on a lease. Typically, operators plug a portion of their wells throughout the life of the structure as the utility of individual wellbores becomes better understood. Once a well is no longer expected to return to production or offer the opportunity to support operations, it represents a liability.

All wells and structures are idle for a portion of their lifetimes, and this is understood to be a normal part of production operations. Infrastructure that no longer produces is generally not considered to threaten the marine environment because reservoir pressure is often depleted to the point where oil does not flow naturally from the old wells and inspections are made regularly to ensure structural integrity. The risk of holding idle inventory falls to the operator, but if the operator is unable to perform its obligations under the terms of the lease and there is no previous working interest or record title owners, then the government is also exposed to the financial risk of nonperformance as the party of last resort.

Idle infrastructure represents a financial liability to the operator. If it is destroyed or damaged in a hurricane, the financial liability may increase greatly because the cost to abandon and remove storm-damaged infrastructure is considerably higher than decommissioning operations under normal, planned conditions. Thus, removing idle wells and structures reduces the financial liability of decommissioning storm-damaged infrastructure and lowers the chance that the federal government will have to perform operations on behalf of bankrupt companies. Plugging idle wells also reduces decommissioning risk because, at least for permanent abandonments, conductor removal decreases the chance the structure will be toppled. If a structure is destroyed, wells that have been abandoned save operators time and expenditure in decommissioning operations.

New system boundaries

Historically, the leasehold has served as the system boundary to determine timing requirements for decommissioning (Fig. 3a). The benefits of using a leasehold for operational decision-making are fairly obvious in terms of scheduling and planning, development flexibility, scale economies and efficiencies, and related factors. Leases and fields are the standard spatial scales for regulating offshore activity because they are considered a reasonable trade-off between efficient operations and government oversight.

NTL 2010-G05 dissolves the lease boundary and redefines the regulatory requirements at the individual wellhead and structure level (Fig. 3b). Criteria for abandonment are now based on the number of years a well or structure has not produced. Wells that have not produced for 5 years or more and are no longer capable of production in paying quantities must be permanently abandoned, temporarily abandoned, or zonally isolated within 3 years from Oct. 15, 2010.

Structures that have not produced for 5 years or more are required to be removed within 5 years from Oct. 15, 2010. Structure removal time lines set an upper time limit on well abandonment activity because before a structure can be removed all wells must be in permanent abandonment status. Thus, the timeline for structure removals imposes a deadline to permanently abandon all wells. For idle structures, therefore, operators will likely perform permanent abandonments at the onset to avoid the higher cost of intermediate (temporary abandonment, zonal isolation) operations.

Safeguards in NTL 2010-G05 provide the operator the option to temporarily abandon wells on producing structures. Temporarily abandoned wells can be reentered in the future, but whether this option is pursued and how frequently it will be utilized is uncertain since temporary abandonment is an intermediate operation that requires additional activity to move into permanent abandonment status. Temporary abandonments that do not lead to future production will raise total abandonment cost.

NTL 2010-G05 will apply to future decommissioning activity. Wells that currently are 4 years idle and do not return to production next year will enter the 5-year idle category next year and will need to be decommissioned, according to the NTL guidelines. Wells that have not produced for the last 3 years and that do not produce in the next 2 years will enter the 5-year idle category in 2 years and will fall under the NTL guidelines at that time.

Within about a decade the Gulf of Mexico will only have wells and structures that have produced within the past 4 years. This will be a very unusual situation for an offshore basin and one with consequences that cannot be entirely foreseen.

NTL 2010-G05 review

The stated purpose of NTL 2010-G05, with an effective date of Oct. 15, 2010, is to "establish guidelines that provide a consistent and systematic approach to determine the future utility of idle infrastructure on active leases and to ensure that all wells, structures, and pipelines on terminated leases and pipelines on terminated pipeline rights-of-way (ROW) are decommissioned within the timeframes established by regulations, conditions of approval, and lease instruments."

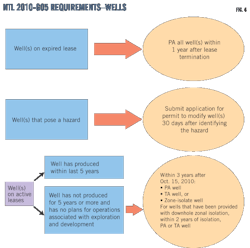

Three classes of wells are specified: wells on expired leases, wells that pose a hazard, and wells on active leases. Three structure classes are defined: structures on terminated leases, structures on active leases, and toppled or otherwise destroyed structures.

Wells on expired leases, wells that pose a hazard, and structures associated with a terminated lease, right of use and easement, or pipeline ROW grant specify decommissioning requirements in accord with current (status quo) regulations. Wells and structures on active leases that have not been used in the past 5 years and toppled (or otherwise destroyed) structures are new categories with new time lines for decommissioning.

Time lines are specified to abandon wells and structures on active leases identified as "no longer useful for operations" and no longer capable of "producing in paying quantities."

The BOEMRE defines a well as "no longer useful for operations" if it "has (a) not been used in the past 5 years (i) for operations associated with E&P or (ii) as infrastructure to support such operations; and (b) no plans (i) for operations associated with E&P or (ii) infrastructure to support such operations."

A platform is defined as "no longer useful for operations" if it "has (a) been toppled or otherwise destroyed; or (b) not been used in the past 5 years (i) for operations associated with E&P or (ii) as infrastructure to support such operations."

The BOEMRE defines producing in paying quantities as production that "yields a positive stream of income after subtracting normal expenses (i.e., operating costs), which include the sum of minimum royalty or actual royalty payments, whichever is greater, and the direct lease operating costs."

The NTL establishes three well classifications (Fig. 4):

I. Wells on Expired Leases—For wells on expired leases, an operator has 1 year after the lease terminates to permanently plug all wells.

II. Wells that Pose a Hazard—For any well that poses a hazard to safety or the environment, operators are required to submit an Application for Permit to Modify to permanently plug the wellbore within 30 days after identifying the hazard.

III. Wells on Active Leases—For any well that has not produced for 5 years or more and is no longer capable of production in paying quantities, the producer must, within 3 years of the effective date of the NTL, permanently plug the well, temporarily abandon the well, or provide the well with downhole zonal isolation and within 2 years either permanently plug or temporarily abandon the well. Downhole zone isolation refers to isolating all hydrocarbon zones by adhering to the plug and testing requirements of 30 CFR 250.1712-1717. Each well in downhole zonal isolation status is equipped with a dry tree and a wellhead capable of monitoring all annuli for sustained pressure.

For wells that have not been used in the past 5 years that are believed to be useful for operations or capable of future production, operators can submit to the regional supervisor of field operations support documentation of the well's usefulness for additional consideration.

NTL 2010-G05 sets these priorities for work to meet the deadlines:

(1) Wells on structures with the highest risk to toppling, are structurally damaged, or are L3/A3 structures.

(2) Wells that were producing oil.

(3) Wells capable of natural flow.

(4) Wells that have casing pressure.

(5) Wells located close to the shoreline, environmentally sensitive areas, or other infrastructure.

For platforms, NTL 2010-G05 establishes three classifications (Fig. 5):

I. Structures on Expired Leases, Right-of-Use and Easements, or Pipeline Right of Way—A platform or other facility associated with a terminated lease, right-of-use and easement, or pipeline ROW grant has within 1 year after the termination date to remove the platform.

II. Structures on Active Leases—A platform or other facility on an active lease that is not being used for E&P operations or as infrastructure to support such operations must be removed no later than 5 years after the effective date of the NTL or within 5 years of the platform meeting the definition of no longer useful for operations, whichever is later.

III. Toppled or Otherwise Destroyed Structures—For a toppled or otherwise destroyed platform, the structure must be removed as soon as possible but no later than 5 years after the effective date of the NTL or within 5 years of the platform meeting the definition of no longer useful for operations, whichever is later.

Model framework

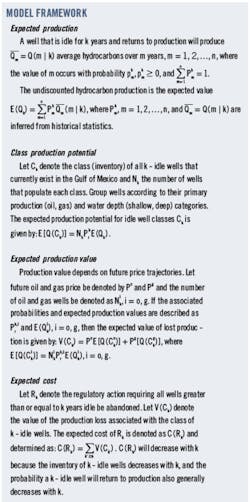

In the model used for this analysis, a well is said to produce in year t if it produced any amount of oil or gas during the year. A well that did not produce during year t is said to be idle in year t. A well that is idle for k years, for k = 1, 2, …, is said to be a k-idle well.

At any point in time, a well is either producing or not producing. A nonproducing (idle) well is either shut-in or temporarily abandoned (TA). Both states are transitory. A well that is shut-in may return to production next year, remain idle, or be permanently abandoned (PA). Similarly, a TA well may return to production next year, remain classified as TA, or be permanently abandoned. A PA well is the final status of a wellbore, and all wells will eventually be captured in this state.

The probability a k-idle well will return to production next year is given by Prk, and the probability that it will remain idle is given by Pik. Because these are the only two states in which a k-idle well can exist, the probability a k-idle well will be permanently abandoned next year is given by 1 – Prk – Pik. The probabilities Prk, Pik, and Pak are a function of idle age, production type, water depth, and other factors.

The most important observable factors impacting transition probabilities are idle age and water depth. Intuitively, one would expect that the longer a well stays idle, the greater the probability it will remain idle. The probability an idle well will return to production is expected to decline with idle age during the first few years of inactivity. Both of these statements can be quantified through empirical analysis.

Wells are abandoned throughout the life cycle of field development, and historically, less than half of permanent abandonments are performed when a structure is removed (Fig. 6). Thus, Pak is not expected to be strongly correlated with idle age. Deepwater wells are expected to have a greater probability to return to production than shallow-water wells reflecting differences in well productivity, potential, capital outlays, and age.

Model results</p>

The expected lost production associated with NTL 2010-G05 is derived from the inventory of k-idle wells, the probability a k-idle well will return to production, and the production a k-idle well is expected to achieve if it comes back on line.

Values are computed on an undiscounted basis, include the current inventory of TA wells, and assume abandoned wells do not return to production. The collective impact of these assumptions will overestimate production loss. Structure removals are not considered to avoid double-counting. Commodity price decks ($40/bbl oil, $4/Mcf gas) and ($120/bbl oil, $12/Mcf gas) bound the scenarios.

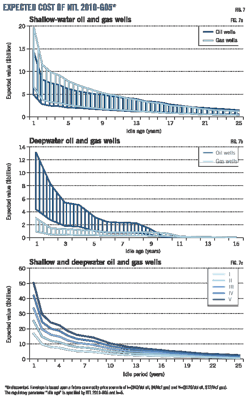

Lost production is depicted as a function of "idle period" for shallow and deepwater oil and gas wells in Figs. 7a and 7b. NTL 2010-G05 specifies the allowable idle age at k = 5 years, but k is a parameter that can range in value anywhere from k = 1 to k = 40 years. The selection of k is arbitrary. As k increases the value of the lost production will decrease, as shown.

In Fig. 7c, a composite profile representing the expected cost of NTL 2010-G05 depicts the total undiscounted, shallow and deepwater, oil and gas lost production potential. For k = 3 the expected production loss ranges between $8.1 billion and $24.2 billion; for k = 5 the expected cost ranges between $6.2 billion and $18.6 billion, and for k = 10 the expected cost ranges between $3 billion and $10 billion. For k ≥20, the maximum production loss is bounded below $4.1 billion.

Operator choice

Operators have a choice to either permanently or temporarily abandon wells that are 5 or more years idle, and the decision will involve an evaluation of the opportunity cost, risk, and short-term capital expenditures. We assume that after a well is abandoned it will lose its future production potential. This is a good assumption for permanent abandonments because access to the wellbore has been effectively lost, but for temporary abandonments, because operators can reenter a TA well, production loss is less certain.

TA wells provide operators the option of returning to the wells in the future, but the extent to which this option will be performed depends on operators' knowledge of the values of their idle wells and structure inventories, which as discussed previously, is both uncertain and incomplete—and, for all practical purposes, unknowable. It is likely that in their desire to limit uncertainty and future expenditures related to the NTL requirements, operators will prefer PA operations.

For wells on idle platforms, wells will be PA'd because the nonproducing status of the structures dictates decommissioning time lines. Operators that perform TA operations and zonal isolations on idle structures will increase their expenditures to carry their wells into PA status prior to structure removal. For wells on producing platforms, operators will need to determine the benefit and cost on an individual well basis, which will be difficult to evaluate.

The future inventory

Within a decade, the Gulf of Mexico will have only a limited inventory of wells and structures that haven't produced for 5 years or more. The future inventory will be quite different from today's, and the important question is whether the benefits of managing the idle inventory and its risks outweigh the potential costs to future production and development.

The benefits of the NTL are elusive and difficult to quantify, but few will argue that wells and structures that no longer serve a useful function, or that are expected to serve no useful function in the future, should accumulate. The problem arises because an operator does not and cannot know the future value of idle inventory. Specifying time lines on removing idle infrastructure will destroy the potential value of the asset.

The cumulative value of lost production depends on the number of years a well or structure is allowed to remain idle before it has to be plugged or removed. Under the current 5-year threshold criterion, the value of the lost production to operators is expected to range between $6.2 to $18.6 billion, depending on future prices of oil and gas. If the regulatory level was implemented on the basis of a 10-year criterion, the value of lost production would be cut in half.

The authors

More Oil & Gas Journal Current Issue Articles

More Oil & Gas Journal Archives Issue Articles

View Oil and Gas Articles on PennEnergy.com