Technologies lower in situ bitumen recovery costs

Costs for recovering bitumen with in situ methods continue to decline, and new technologies are bound to reduce costs further, according to Harbir Chhina, executive vice-president enhanced oil development and new resource plays for Cenovus Energy Inc., Calgary.

In an interview with Oil & Gas Journal, Chhina said that technologies such as in situ steam-assisted gravity drainage are still realatively new and further optimization of these technologies is likely.

He said Cenovus has about 50 ongoing research and development projects and plans to implement one new commercial technology each year. Some technologies that he expects will become commercial include expansion of wedge wells, in situ combustion, low-pressure SAGD, and solvent aided processes,

Cenovus

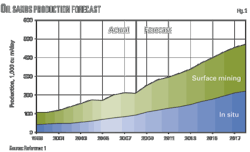

Formed from the assets of Encana Corp., Cenovus began operating as a separate company on Dec. 1, 2009. Its main bitumen plays are in the Foster Creek, Christina Lake, Borealis, and Greater Pelican regions in Alberta (Fig. 1).

Cenovus also owns 50% of the ConocoPhillips-operated Wood River refinery in Illinois and the Borger refinery in Texas. The refineries have a combined heavy-oil refining capacity of 275,000 b/d.

Foster Creek was the first commercial SAGD project to come on stream. Pilot production started in 1996 and it became a commercial project in 2001. Chhina noted that earlier this year Foster Creek became the first SAGD project in Alberta that had paid out.

Cenovus develops its bitumen projects in small, manageable segments with 30,000-40,000 b/d production capacity, enabling the company continually to improve the scheme by learning from each successive phase and by using innovative technology and practices.

Foster Creek Phases A-E (Fig. 2) now produce 105,000 b/d from 160 wells, and Chhina said the project's ramp up to 105,000 b/d was one of the few times that a SAGD project was delivered on time and met production expectations. Fig. 3 shows a typical multiwell SAGD pad at Foster Creek.

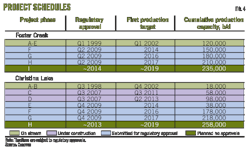

Cenovus plans to add Phases F-H to Foster Creek, with each phase adding 30,000 b/d of production capacity. Cenovous recently announced an additional expansion, Phase I, that it expects will add 25,000 b/d of production capacity. After completion of these phases in about 2019, Foster Creek will have a 235,000 b/d production capacity (Fig. 4).

Christina Lake is Cenovus's other ongoing commercial SAGD project (Fig. 5). Commercial production at Christina Lake started in 2002. Currently the project produces from Phases A and B about 15,000 b/d from 17 wells.

At Christina Lake, Cenovus has under construction Phases C and D and has plans for Phases E-H. Each phase will add 40,000 b/d of capacity, with production capacity reaching 258,000 b/d after completion of Phase H in about 2019 (Fig. 4).

Cenovus holds a 50% working interest in both Foster Creek and Christina Lake with ConocoPhillips holding the remaining 50%.

At yearend 2009, Cenovus had a land position of 7.8 million acres and held 2.1 billion boe proved and probable reserves, with bitumen accounting for 1.3 billion bbl.

Cenovus notes that an independent evaluator determined that the company's acreage has 137 billion bbl of bitumen initially in place with 56 billion bbl falling in the discovered category.

Besides the expansions at Foster Creek and Christina Lake, the company has plans to develop other projects that would increase the net production to Cenovus to 300,000 b/d by 2019. When completed, all the projects listed in Fig. 6 would have a 430,000 b/d of net to Cenovus bitumen production capacity.

Chhina noted that Foster Creek is economic (9% rate of return) at a $40 WTI oil price. He said the current operating costs including fuel are $11/bbl and the current bitumen price at the wellhead is $55.40/bbl.

Foster Creek has 2.3 steam-oil ratios without considering wedge wells, and Chhina believes the SORs can decrease to 1.7-1.8 compared with 5-7 SORs in some of the other SAGD projects in Alberta.

Technology development

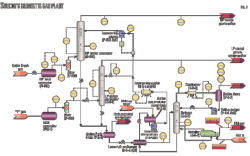

Chhina said several technologies have brought down the cost of bitumen production for the Cenovus projects and expects a number of other innovations will bring down the cost further (Fig. 7). Cenovus believes that implementing new technologies at its oil sands operations could improve its supply costs by $10-15/bbl. Cenovus defines supply cost as the average West Texas Intermediate oil price required for a 9% after tax cost of capital return.

He noted that after SAGD was working in pilot projects, one technology that improved the process about 15 years ago was an improved liner design. In the SAGD well laterals, Cenovus runs 7-in. slotted liners that hang on a thermal packer in 95⁄8-in. casing. The slotted liners have some areas that are blanked and the slot size can vary between the injection and producing lateral.

Chhina said during the SAGD pilot stage, the first patent received was for a coiled-tubing string with fiber optics, multiple thermocouples, and pressure sensors for evaluating every meter of a well.

Downhole pumps

The next technology developed that brought down Foster Creek costs was the use of electric submersible pumps. Chhina explained that gas lift was initially used at Foster Creek but this led to a need for high reservoir pressures of about 2,500-3,000 kPa at the 400-450 m reservoir depth.

Higher temperatures and pressures increase the SOR that is the main metric for controlling capital efficiencies, operating costs, water usage, and emissions, he said.

To lower the SOR, he explained that the company started looking at ESPs but in the early 2000s, ESPs could only operate at about a 200° C. maximum temperature, and therefore the company with the help of vendors started to design its own ESPs with the goal of operating at 1,000 kPa and 210° C.

Chhina said the first ESP tried in 2001 still had to work at a 2,500-3,000 kP reservoir pressure, but the ESP design has improved and currently the ESPs in 210° C. temperature and lower reservoir pressures obtain a run life of about 13 months compared with 3-6 months run times 9-10 years ago.

Improvements made to the pumps included installing different seals and also adding the capability for pumping small amounts of fine sediments as well as some gas, he said.

Chhina noted that since starting to use ESPs, the SORs are less; so that on a per-barrel basis the operation has lower emissions, a 15% decrease in water use, and a 12% reduction in steam generation costs.

Most of the Cenovus SAGD wells now use ESPs.

Currently Cenovus has under development an external circumferential piston pump. The ECP is driven mechanically by sucker rods in a similar fashion to a progressing cavity pump. But Chhina said PCPs cannot pump at high rates, whereas the ECP with several pump stages, as in ESPs, can move large amounts of fluids.

Low-pressure SAGD

Cenovus is now in the process of reducing pressure in the reservoir to 1,000-1,500 kPa during the next couple of years. It will start on a couple of patterns at Foster Creek.

In low-pressure SAGD, the operating pressure decreases and also the temperature to which the reservoir needs to be heated also decreases. The lower pressure decreases individual well production rates, but because each well needs less steam, it frees steam capacity for other well pairs and therefore can increase overall production levels, Chhina explained.

In the current process the company injects steam for about 4-5 years for recovering about two thirds of the bitumen before shutting off the steam and going to a blowdown stage. Cenovus also sometimes injects noncondensable gases, usually methane, after shutting off the steam in order to maintain reservoir pressure.

Wedge wells

Wedge wells are another technology that Cenovus uses to improve recovery (Fig. 8). The company drills SAGD well pairs on about a 100-m spacing. It notes that after about 2 years of production, the steam chambers between pairs begin to comingle and eventually overlap. This leaves a wedge of unproduced oil between the well pairs at the base of the reservoir.

In 2004, it started a wedge well pilot at Foster Creek to extract more oil from this previously unreachable wedge of the reservoir. These wells have a single, horizontal lateral between two SAGD well pairs.

The company estimates that the wedge wells have increased recovery by about 10%. Each wedge well can produce about 600-800 b/d, and because wedge wells require minimal steam, the wells will reduce the per-barrel operating costs, water use, and emissions.

At yearend 2009, wedge wells account for 15% of Foster Creek production and Cenovus has initiated a wedge well pilot at Christina Lake.

Chhina attributed the wedge well success at Foster Creek to the unique characteristics of the reservoir. The project has the deepest reservoir producing under SAGD and was the only reservoir in the area that produced under cold primary conditions because of its lighter 10-12° gravity oil and less viscous oil that has a 100,000 cp viscosity compared with the several million centipoise bitumen viscosity in other areas.

The company now has 36 horizontal wedge wells that produce 15,000-16,000 b/d. Chhina said that out of the 36 wells about 31 are on production while 5 wells receive some slugs of steam.

He explained that the Foster Creek plant is not designed for the wedge well production; therefore it restricts total production. But because the wedge wells produce without steam they are put online instead of new SAGD well pairs, he said.

Chhina noted that the plan now is to produce every SAGD pair for 4 years and then add a wedge well between the SAGD pairs.

SAP

Cenovus also is testing the use of a solvent-aided process for recovering bitumen. The process involves adding a liquid solvent, such as butane, to the steam. The company notes that the early indications are that the process increases bitumen recovery rates and decreases the amount of steam needed. An initial trial at its former Senlac, Saskatchewan property, which ended in 2002, showed a 30-40% improvement in production and SOR.

Cenovus began testing SAP in Alberta at Christina Lake in 2004 and began in second-quarter 2009 a dedicated isolated SAP test well at Christina Lake. Chhina said the pilots had proven that about 90% of the butanes injected could be recovered, which is greater than the 80% recovery needed for a commercial project.

SAP also may allow a 130-m distance between well pairs, which is greater than the current 100-m SAGD spacing, Chhina noted.

SAP is part of the company's application for the Narrows Lake project. If implemented at Narrows Lake, it would be the first commercial project using SAP. Narrows Lake is an extension of Christina Lake.

The Narrows Lake project application calls for two or three phases of SAP or SAGD with SAP to obtain a total production capacity of 130,000 b/d.

Boilers

Cenovus generates 93% quality steam, unlike other projects that generate 70-80% quality steam. Chhina explained that the process for obtaining 93% quality steam involves generating 80% in a normal boiler and then running the remaining 20% quality steam into a blowdown boiler.

This process reduces operating costs, emissions, and needed makeup water, he said. Previously the company had to remove heat before being able to dispose of the 20% quality steam. Chhina said now the company only has to dispose of 7% quality steam and some of that goes into the boiler make up stream.

Fig. 9 shows boilers at Foster Creek.

Other technologies

Since electrifying well pads, Cenovus has started to use electric drilling rigs at Foster Creek. These rigs are quieter, have less effect on vegetation, and reduce local emissions by 65% compared with diesel rigs.

Cenovus has an 80-Mw cogeneration capability at Foster Creek of which 39 Mw is used in the operations.

Chhina noted that, 6-7 years ago, the company tested the Vapex process, which uses propane and no steam. He said that it may be possible to make the process work, but it will need time and additional trials to make it commercial.

In situ combustion is another technology that Chhina expects will become commercial (Fig. 10). Cenovus has a pilot combustion project running for the last 31⁄2 years.

Chhina noted that the company was forced to stop producing gas from above the bitumen because of government restrictions that came into effect about 8 years ago. He disagrees with the need the restrict gas production because he believes low-pressure SAGD is more effective.

But because of these restrictions, the company began injecting air and produced gas into the gas cap in the Wabiskaw reservoir, northwest of Foster Creek (Fig. 10). The combustion obtained reservoir pressures of 400-450° C. in an observation well. The company was allowed to do this because it held rights to both the gas and bitumen.

Cenovus also has plans for a combustion pilot for the Clearwater reservoir, which is planned for 2012.

More Oil & Gas Journal Current Issue Articles

More Oil & Gas Journal Archives Issue Articles

View Oil and Gas Articles on PennEnergy.com