Adopting E85 provides way over 'blend wall'

Approval soon of gasoline ethanol blends of 15% (E15) by the US Environmental Protection Agency appears nearly certain and offers the illusion of a path to alleviate the immediate "blend wall" issues for refiners and importers posed by conflicting requirements of the 1990 Clean Air Act and the 2007 Energy Independence and Security Act.

Promotion of E85, however, may offer the least disruptive path to achieve EISA's Renewable Fuels Standards targets.

The abundance of existing flexible-fuel vehicles and the announcements of future FFV production rates have already set the stage for massive sales growth. Given the poor fuel economy associated with E85, however, consumers will need additional economic incentive to make the numbers work and education on the issues related to E85.

Blend wall

In the next few months, EPA will announce whether to grant a waiver to the 1990 Clean Air Act's limit on blending ethanol into gasoline at a maximum rate of 10% (the "blend wall"). This issue has become critical as a result of the conflict between the Clean Air Act and EISA's minimum RFS targets for ethanol that rise each year and peak at more than 30 billion gal in 2022.

The 2010 level of 12 billion gal is equivalent to 8.8% of the US gasoline supply and is precariously approaching its practical logistic limit. By 2022, this level will be in the 20-25% range if RFS targets are met.

Without resolution, refiners and importers will soon be forced to violate either the Clean Air Act or EISA—or stop selling gasoline. While industry speculation has centered on EPA's raising the 10% limit, another alternative appears forgotten in the debate: increasing E85 sales.

EPA is currently conducting tests on a variety of vehicles to determine their ability to tolerate blends of 15% ethanol. It is assumed that model year 2001 and newer cars can safely run E15 but older vehicles are likely to have operational problems. EPA testing will determine this break point.

The continuing need of E10 for older cars would create a bifurcated gasoline supply with "old gas" and "new gas." The agency has also been requested by Archer Daniels Midland Corp. to consider an E12 alternative but has said that option would require extensive testing. None has been conducted at this time.

Many industry groups had supported an E12 on the assumption that it could be run in virtually all existing autos. But if EPA approved E12 without further testing of this assumption, the agency would likely be forced to approve the fuel for the same model years as those approved for E15. Therefore, the gasoline supply would still be bifurcated.

Most of the renewable fuel mandates are to be met either by cellulosic ethanol or conventional ethanol predominantly produced from corn. Conventional ethanol targets are being met and will peak in 2015 at 15 billion gal. Cellulosic targets have already been delayed, however, and future development remains uncertain.

Because of this uncertainty, Turner, Mason & Co., Dallas, has evaluated two scenarios (Table 1). The first assumes the full targets, both conventional and cellulosic, will be met; the second assumes continued delays in cellulosic development and a reduction in the targets.

'Obligated parties'

Ethanol producers have long worried that the approach of the blend wall will inhibit their production capabilities, but their worries have been unfounded. EISA has mandated rising ethanol use, but the responsibility to place the product into the market does not rest with the ethanol producers, but with refiners and importers. They are, in the vernacular of the EPA, the "obligated parties" and shoulder the burden of ensuring the product reaches the consumer.

Each year, every refiner and importer is notified of the Renewable Volume Obligation, which is the minimum renewable fuels percentage (essentially ethanol and biodiesel) that must be included in their total gasoline and diesel sales. EPA does not specify how the refiner-importer achieves its RVO, but failure to attain it in a 2-year period may result in substantial fines.

The impending approval of E15 will merely provide one more option in this regard. Since there has always been an outlet for increasing ethanol production via E85, the concept of a blend wall is an illusion. Nevertheless, E85 sales remain insignificant and the complexities of introducing E15 are enormous.

The conversion to higher ethanol blends is unlike any other transition in gasoline history. The introduction of unleaded gasoline was forced by the production of automobiles that can only run on unleaded fuel, and reformulated gasoline was mandated over broad geographic areas by EPA. In both cases, the consumer and marketer had no choice in the conversion. In this instance, however, EPA cannot require marketers or, most importantly, consumers to convert to E15.

Of critical importance, and seemingly forgotten, is the fact that not only does the Clean Air Act limit ethanol to 10% but EPA regulations concerning reformulated gasoline also have limitations at about the same level. So Turner, Mason feels it is premature to assume E15 will be permitted in RFG areas (35% of the US gasoline market). Similarly, multiple state regulations, particularly California, may impede development.

Two options

Should E15 move ahead, there are two options for its introduction into the retail segment.

The more expensive approach would be to add E15 sales to an existing E10 station. This would require additional underground storage tanks and would necessitate substantial capital investment. Because the consumer would quickly realize the fuel economy is lower, an ongoing price subsidy would also be required. The station may also bear some legal liability that could result from misfueling.

The second approach is virtually no cost but much higher risk: conversion of the E10 station to E15. This approach brings the risk that if E15 is not accepted, sales will plummet for both the marketer and refiner. The first stations to market E15 in any area have the highest risk in that they are selling to a consumer base that is largely unaware of their product.

Even the pump labels EPA is expected to require will act as a deterrent by reminding customers that E15 is not recommended for many vehicles. The consumer would feel more comfortable if a large number of stations, across many brands, were converted at one time.

But antitrust laws prohibit refiners from coordinating such actions. As with the first option, an ongoing subsidy by the refiner would be necessary to compete with the E10 station across the street.

E85 solution

Given the current situation, the less risky solution would be a more aggressive promotion of E85. Even though it was originally seen as the ultimate solution for meeting the RFS requirements, E85 development has languished in recent years. As of June 2010, only 2,326 stations in the US sell the product and sales in 2008 (the latest year for which data are available) were a mere 73.5 million gal, or 0.05% of the gasoline/ethanol market.1

Not a limiting factor (or soon not to be) is the number of vehicles that can use E85. There are about 8.7 million Flexible Fuel Vehicles that can run any fuel from 0-85% ethanol on the road today, and General Motors, Ford, and Chrysler have all pledged to produce half of their 2012 model year and later vehicles as FFVs. Unfortunately however, a recent survey indicates that 68% of current FFV owners are not aware their vehicles can run E85.2

As the refiner-importer's RVO gradually increases and rises above the equivalent of 10% ethanol in gasoline, the first year above 10% will only have a marginal degree of noncompliance. This small level lends itself to a modest remedy. The conversion of an E10 gal to E85 has up to 15 times the effect of an E10 gal to E15 gal.

Consumer acceptance is also likely to be higher in that advertising would be necessary to convince consumers that E15 is not harmful to their cars, compared to simply educating them that their FFV vehicles were specifically designed to run on E85.

Perhaps the most compelling support for E85 is that it is already fully compliant with all federal and state regulations in all markets.

An important sensitivity to the E85 consumer is the reduced fuel economy vs. other fuel grades. While the btu content of neat ethanol is 34% below that of clear gasoline (E0), EPA tests on 2007 model automobiles yielded an average mileage reduction of 26.6% for E85.3 As virtually no E0 is now available, the alternative available to the consumer would be E10, which would have a mileage difference of 24.2%. This means the consumer must see an E85 price at least 25% below E10 to balance the price with fuel economy.

The actual spread has not achieved this level during the past year and has only averaged a 16.6% discount.4 A subsidy of around 22¢/gal would have been necessary to have achieved the 25% discount (Fig. 1).

Model projections

To test the practicality of dramatically increasing E85 sales, Turner, Mason developed models for two scenarios: Full RFS Compliance and Reduced Cellulosic Growth.

In both cases, E10 was maintained as the principal grade (with ethanol content actually limited to 9% to represent logistical limitations), and E85, assumed to be 77.5% on a yearly basis (the oxygen content of E85 ranges from 70 to 85%), was used to balance the required ethanol production.

The required volume of E85 was computed along with the number of FFVs that would be necessary to consume the volume. Each FFV was assumed to be a 20-mpg vehicle using E0 (which equates to 14.7 mpg on E85) driving 10,000 miles/year.

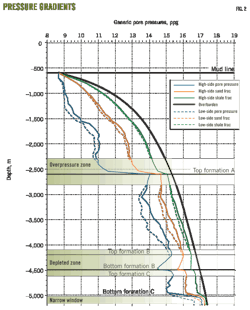

In the maximum ethanol case, Full RFS Compliance, E85 would represent slightly less than 20% of the total gasoline/ethanol fuel supply in 2022 and would require 43% of the estimated FFVs to use E85 (Fig. 2).

In the Reduced Cellulosic Growth case, E85 demand would peak in 2022 at slightly more than 6% of the fuel supply, while FFV requirements would peak in 2015 at 23% of the FFV fleet (Fig. 3).

References

1. E85Prices.com.

2. "Alternative and Advanced Vehicles: Flexible Fuel Vehicles." National Renewable Energy Laboratory, DOE (9/17/2007). Alternative Fuels and Advanced Vehicles Data Center.

3. Roberts, Matthew C., "E85 and Fuel Efficiency: An Empirical Analysis of 2007 EPA Test Data," Department of Agricultural, Environmental, and Development Economics, Ohio State University, Columbus.

4. E85Prices.com.

The authors

More Oil & Gas Journal Current Issue Articles

More Oil & Gas Journal Archives Issue Articles

View Oil and Gas Articles on PennEnergy.com