Market changes vex Russian gas policies

Adapted from a presentation prepared for the Russian Event sponsored by the Center for Global Affairs, New York University, and The Carnegie Corp., Feb. 26, 2010.

While oil provides most of the energy-export revenues for Russia, natural gas is the source of the principal energy-policy challenges that the country faces. Although roughly 70% of the oil and gas export revenues are for crude oil and refined products, Russia's oil-policy options are limited since the country is largely a price taker and has little or no control over world oil prices. Somewhat ironically, however, many of its energy-policy challenges are rooted in gas pricing issues where it does exert control.

Some of those issues are:

• Russia's pricing disputes with the Ukraine, which have led to European supply disruptions and raised supply-security issues in the European Union.

• Its pricing policies toward the Central Asian republics of the old Soviet Union.

• Its need to retain Gazprom's export monopoly for financial reasons, further aggravating its relations with an EU that is aggressively promoting gas-market liberalization.

• The funding of the very large capital expenditure requirements that it faces as it tries to develop its arctic gas reserves on the Yamal Peninsula and in the Barents Sea.

While future oil price levels are highly uncertain, an analysis of the effect of oil prices on the Russian economy is relatively straightforward. But no similar analysis is possible for gas since there is not yet a "world gas price." Gas prices usually have been set locally, and although international LNG trade is introducing global price competition, it is still in its early stages.

Dysfunctional system

Unfortunately for Russia, the country has inherited a dysfunctional gas pricing system from its command-and-control period. That system was designed to encourage the use of gas to replace coal, but in the early 2000s domestic prices were as little as a quarter of export prices.

The effect has been to promote overconsumption of gas that otherwise could be exported and to accelerate the need for costly industry investment in new supply and infrastructure. Russian policy now proposes an ultimate closing of the gap—but over an extended period.

The low-pricing system also was applied to the former Soviet republics such as the Ukraine and Belarus. The current pricing disputes between Russia and its neighbors thus might be explained simply as moving customers toward a more-liberalized market-pricing system. But the fact that the price increases sometimes appear selective and arbitrary reinforces the perception that they are politically motivated.

Since only 25% of Russian gas is exported (vs. 75% of Russian oil), the cash flow available to Gazprom for reinvestment is badly impaired by low domestic prices. This is a major reason for Gazprom's export monopoly and the requirement that independent producers sell only into domestic markets.

Ukrainian dispute

One of the most difficult geopolitical issues in Europe has been the ongoing gas-pricing dispute between Russia and the Ukraine.

To enforce its pricing and revenue-collection demands, Russia has periodically curtailed deliveries. But the Ukraine has preempted transit gas, disrupting onward shipments to other European customers. The problem was particularly acute in the winter of 2008-09. While much of the EU suffered, Romania and Bulgaria were especially hard-hit.

Russia contends that the dispute is commercial, not geopolitical, and that it is a reliable supplier. But the EU tends to view the disruptions as efforts to discipline a former member of the Soviet Union and as evidence that Russia is prepared to use its gas supply as a political instrument. As an advocate of liberalized energy markets, moreover, the EU does not approve of the Gazprom export monopoly.

In 2008, Russian supply represented 29% of EU consumption and 55% of EU imports. Most forecasts indicate that Russian market share will continue to rise as alternative, nearby supplies are not growing or are in decline.

Not surprisingly, the EU is actively pursuing options to diversify gas supply.

Russia contends that it has never directly reduced supply to its EU customers. It further argues that it demonstrates its reliability by investing, at great cost, in diversified supply routes. The election of Russian-leaning Viktor Yanukovych as Ukraine's President in February may improve relations between the two countries, but it is not clear that it will do much to alleviate European customer concerns.

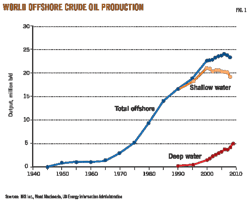

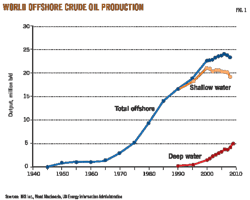

To bypass the Ukraine, Russia built the Yamal pipeline through Poland in 1997 and has proposed two lines: Nord-stream from West Siberia via the Baltic and Southstream from the Caspian via the Black Sea. Both are high-pressure marine lines, and Southstream would lie in deep water. They thus are expensive alternatives to direct Ukrainian transit (Fig. 1).

EU targets Caspian

While liquefied natural gas provides some diversification, a major EU target is the extensive gas reserves in the Caspian region.

Russia lost control of Caspian oil when the BTC oil pipeline was completed in 2005 from Baku, Azerbaijan, to Ceyhan, Turkey, on the Mediterranean.

The EU's preferred Nabucco gas pipeline also could start in Baku, tapping Azerbaijan's Shah Deniz gas reserves. It is designed to transit Georgia, Turkey, Bulgaria, Romania, and Hungary, delivering gas to the Austrian border.

In theory, the cost of moving gas from either Azerbaijan or the Russian reserves in the North Caspian favors the Russian option, but it involves Ukrainian transit (Fig. 2).

Russia's Ukrainian bypass option, Southstream, is much more costly. But since Azerbaijan has already committed some of its gas reserves to a Turkish long-term contract, the remaining reserves are not large enough to support a long-distance pipeline such as Nabucco. And, despite talk of additional supplies—such as from Iraq, Kurdistan, or Egypt—none of these appear certain enough to support the line at this point.

Three sources

There are three sources of gas in the region that could provide the necessary supply: Turkmenistan, Russia (perhaps supplemented by Caspian imports), and Iran. For geopolitical reasons, the EU—and the US—would clearly prefer Turkmenistan.

The largest oil and gas reserves are on the eastern side of the Caspian Sea: oil in Kazakhstan and gas in Turkmenistan. But the jurisdiction of the Caspian seabed is in dispute among the adjoining states: Azerbaijan, Russia, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, and Iran.

The BTC oil pipeline works because Kazakh oil can be tankered across the Caspian to the oil terminus in Baku. But gas must be piped, and, indeed, the TransCaspian pipeline from Turkmenistan to Baku has been promoted as a solution to the supply problem. But without a negotiated solution to the seabed jurisdictional dispute, or a willingness of Turkmenistan to defy its neighbors, implementation of the TransCaspian line remains in question.

Strangely enough, Russia has a Ukrainian bypass option from the region, the economics of which are superior to its Southstream proposal: expanding its existing Bluestream pipeline crossing the Black Sea from Russia to Turkey in order to feed Nabucco.

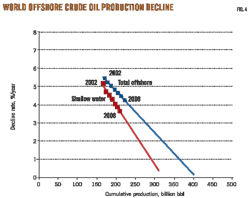

The economics of deepwater pipelining, of which Bluestream is a pioneer, are very sensitive to the length of the underwater route. Bluestream's route from the north side of the Black Sea to Turkey is much shorter than Southstream's east-to-west route from Russia to Bulgaria. And, since Bluestream already has unutilized spare capacity, the economics of expanding it are even better than the hypothetical comparison here (Fig. 3).

Nabucco always envisioned an ultimate extension to the Middle East, most likely Iran, but, in the current dispute over Iranian nuclear ambitions, that also appears unlikely.

Russia's problems

At the same time, Russia has problems of its own.

China has emerged as a competitor for Turkmen gas by completing a link to its west-to-east pipeline serving Shanghai. This pipeline, successfully built under command-and-control logic, is 25% longer than the pipeline from Alaska's North Slope to Chicago that North America has been trying unsuccessfully to justify for more than 30 years.

Although the very large reserves in Turkmenistan will support multiple buyers, Russia can no longer count on a bargaining advantage from Turkmen frustration with Nabucco's delays (Fig. 4).

Russia had linked Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan to the Russian pipeline grid during the Soviet era. And after their independence, gas purchase prices remained low, consistent with Russian pricing policies. Russia's monopsony buying position enabled it to avoid sharing its export revenues from European sales.

Russia has a transportation cost advantage via the Ukraine, and the Caspian gas suppliers are less concerned about the Ukrainian transit issue. Thus a bargaining option for Russia in its negotiations was a price increase that would be difficult for competitors to match.

In 2009, Russia did just that with somewhat disastrous consequences. It raised the price for Turkmen gas from $130/thousand cu m (Mcm) to $300/Mcm, a 130% increase between the first half of 2008 and the first half of 2009, and the increase granted to Azerbaijan was even greater (Fig. 5).

In 2008, the margin between Russia's purchase price and the Austrian border price was sufficient to cover the estimated costs of the Southstream option as well as the direction option. Actual costs involving infrastructure expansion probably are somewhat lower.

But weakening prices in Europe in 2009 put Gazprom in the awkward position of paying Turkmenistan more for gas than it was selling it for in Western Europe.

LNG competition

Russia's problems have been compounded by the emergence of LNG competition in Northwestern Europe that threatens to weaken gas prices still further.

The philosophical conflict between commodity gas-to-gas pricing in the liberalized North American and UK markets and the continent's adherence to oil-linked, long-term contract pricing was finally joined in late 2009.

Growing LNG surpluses transmitted North America's very weak pricing to Northern Europe via LNG terminals and UK pipeline links to the continent. The Russian price at the German border fell 30% between 2008 and the last 9 months of 2009; the price at the Dutch Title Transfer Facility (TTF) Hub on Germany's western border fell by 55% (Fig. 6).

While the current physical capacity for LNG imports to displace continental pipeline supply is limited, Russia's exports still were seriously affected. Some customers reduced their takes below contractual take-or-pay minimum levels. And Russia's total gas production in 2009 was down 13% from 2008. Much of the decline was attributable to export markets. The LNG competition led Gazprom to renegotiate some long-term contracts, reportedly including up to 15% of spot market indexation in the pricing term.

Weak North Atlantic pricing is likely to persist, even after economic recovery, since North American shale gas developments seem likely to provide continuing supply at prices below oil parity. And with growth of North European LNG import terminal capacity, the continental LNG "invasion" is likely to continue.

The potential for a loss of export revenue places Russian policies of using export revenues to fund costly arctic investments at risk. It also threatens the economic feasibility of its efforts to control Caspian supplies by costly Ukrainian-bypass investments or by offering pricing incentives to Caspian producers.

Policy in disarray

Russia has been using a gas-pricing system that retains favorable prices for domestic markets but generates revenues from higher-priced continental exports to fund costly investment in new arctic supplies and new infrastructure. To its major European customers, the infrastructure investments sometimes appear politically motivated.

This policy is now in disarray as continental prices have weakened and threaten to undermine the traditional continental oil-linked pricing system.

How Russia resolves its current dilemma will affect its:

• Strained relations with the EU.

• Relations with its former republics, including buyers such as the Ukraine and Belarus and sellers such as Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan.

• Domestic demand, which has been subsidized by low prices.

• Ability to generate funds for investments in the Arctic.

At this point, it is not clear how this all will work out.

The author

More Oil & Gas Journal Current Issue Articles

More Oil & Gas Journal Archives Issue Articles

View Oil and Gas Articles on PennEnergy.com