Historically, asset price booms have been accompanied by arguments that a "new paradigm" has been reached, whether the issue is 19th Century railroad stocks, 1920s agricultural prices, or dot-com stocks in the 1990s. Every bubble has deflated, ignoring the chorus of opinion to the contrary, and mineral prices are not immune.

Oil, however, has been the primary exception, with post-1973 prices remaining about 50% above the historical trend, leading many to think that it is not subject to the market forces that affect other commodities. True, prices during the past decade have been extraordinarily high, although the increase was not unanticipated; some had warned of more-volatile prices due to market tightness. Even so, prices have been far above either predicted or historical levels, and with economic recovery just beginning and prices remaining above $70/bbl (as of this writing), many are predicting that prices will recover, reaching $100/bbl or more within a few years and climbing from there. The US Department of Energy, for example, predicts prices at $123/bbl in 2030, while the International Energy Agency expects them to be $115/bbl. Many, particularly in the investment and peak oil communities, see them likely to be even higher.

The arguments are broadly held: Non-OPEC has peaked (more or less); demand will soar, as Asian economies boom and prices prove ineffective in reducing consumption; members of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries won't (or can't) raise capacity to meet new demand; and costs have risen, forming a new floor. The amazing thing is that all of these arguments were made in the early 1980s, when prices had dropped from the 1980 peak, but remained two to three times higher than pre-1979 levels. Indeed, in the months before the 1986 oil price collapse, the consensus was that prices would soon recover to more "normal" levels.

Is the price likely to remain in the $70-80/bbl range, which would be at least three times the historical average? If, as some argue, costs are now permanently higher due to depletion and the need to exploit more-difficult deposits, this could mean that the new "floor" price is likely to be much higher than before. Alternatively, if the cost increases of the past few years were mostly cyclical, prices should drop to something closer to the historical level of $30/bbl.

Cyclical increase

Upstream costs have increased sharply since 2000, and many believe that this will result in a long period of elevated prices, with estimates in the range of $50-70/bbl for the marginal cost of production. However, there are many reasons to believe that higher costs reflect a cyclical increase rather than a change in the long-term marginal cost of production.

First, costs increased abruptly, doubling from 2004 to 2008, which implies that long-term depletion or other geological factors are not to blame. Second, as much as half of the increase was in the price of steel and cement, two components which are historically highly cyclical and which are not resource-constrained.

There appear to be two relatively unconnected factors at work: Economic boom periods create higher inflation, especially for input factors such as steel and cement (estimated to account for over a third of oil field development costs), as well as labor to some degree.

However, the industry has its own cost cycle, which is closely related to oil prices, as prices determine cash flow and many companies invest on the basis of their cash flow. Higher demand for upstream services and equipment can raise personnel and equipment costs, but primarily if capacity utilization is not depressed.

Previous cycles

In the late 1970s and again in the mid-1990s, higher prices led to rising costs. However, in the first case, widespread inflation was also a contributing factor, and in the second, the price increase was relatively mild and quick—but, even so, resulted in factor costs for the industry responding to higher usage.

Generally speaking, it can take several years after the peak for prices and costs to come down, but a market collapse (recession for elements like steel, oil price collapse for rig rates) can bring them down within 6 months.

North American costs, whether onshore US and Canada or Gulf of Mexico dayrates for jack ups, appear to be much more flexible than other costs, due to greater equipment fungibility and market freedom.

Drivers of costs

There are two primary drivers of upstream industry costs: general economic conditions and industry conditions. The best way to consider it is rate of acceleration-deceleration or, if possible, capacity utilization.

Rapid economic growth usually means that commodity prices (for the industry, steel, cement, and, to a degree, labor) will be under stress and rise, only moderating as new capacity comes on line or a significant slowdown of economic activity occurs (Fig. 1).

Needless to say, there are other factors that can be important, such as the long-term growth in competition and adoption of the basic oxygen smelting process in the steel industry, which reduced costs and brought down prices in the 1960s and again after 1980.

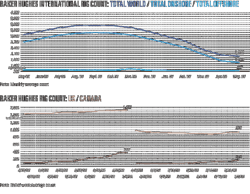

In terms of costs for the oil industry, acceleration-deceleration of effort, which is closely related to capacity utilization, seems to explain inflation in specialized costs, such as skilled labor and drilling rig rates. Fig. 2 shows quarterly rig rates in the Gulf of Mexico according to current capacity utilization rates. The data conform very nicely to theory. Of course, this does not include the impact of a gradual shift to more-sophisticated rigs.

Depletion effects

In theory, the industry always moves from larger to smaller, shallower to deeper fields, although showing this empirically is difficult because of the many other variables (taxes, infrastructure, geology) that affect a field's value.

However, looking at a given area, such as Texas, the analyst can see that, for example, well productivity declines over the long term (Fig. 3), which should translate into higher costs.

In various regions around the world, a 4%/year decline appears to be common, although with a lot of variation. Well depth, on the other hand, does not show strong trends, even in the US and Canada, implying that drilling deeper occurs only gradually in large provinces.

Technological change

Although fears of sudden long-term technological change (or advances in knowledge) disrupting markets are common, actual instances of such are rare. The most prominent exception has been the development of fracturing technologies for the production of shale gas, which has overwhelmed expectations of the need for large-scale imports of LNG. However, there is often a combination of greater supply and lower costs, as the new technologies make previously inaccessible resources viable. Thus, costs might not actually be affected, depending on the specific case.

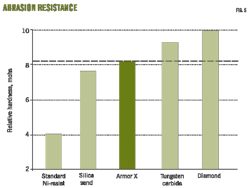

But technological change takes two forms: evolutionary and revolutionary. Evolutionary progress involves small-scale, incremental change that can, over time, improve productivity and reduce costs. Better steels and drillbits, for example, can make drilling any given well cheaper. Improvements in seismic technology have raised the success ratio for exploratory wells in the US from 30% a decade ago to 70% now.

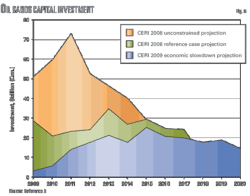

Over the long term, the various improvements appear to reduce costs by something on the order of 2%/year, based on admittedly complex evidence. Thus, in Fig. 4, the cost of producing oil sands in Canada appears to have fallen sharply in the mid-1980s with oil prices depressing factor inputs (and closing uneconomic projects), but longer term, improvements in processes led to a continuing decrease in costs—which was ended subsequently when pressures on the infrastructure reversed the decline.

Costs, flexibility

Obviously, steel and cement prices will be largely driven by changes in the global economy, but a mean-reverting model tends to serve best in projections of costs and flexibility, with an assumption of a long-term decline in the background due to technological change. For rig prices, the issue is more complex as the market is not as fluid as it is for steel and cement. Labor can be moved rapidly and cheaply, but a deepwater rig requires a significant price differential between markets to travel.

The factors affecting cost flexibility would seem to be:

• Complexity of the equipment. Greater flexibility reduces competition, while less complexity increases fungibility and generates pressure on costs.

• Market flexibility. Determined by:

–Size of market;

–Number of operators; and

–Distance to nearby markets.

• Cost/lead time of resource (where cost is judged relative to prices). High-cost resources are first to be abandoned, experience low utilization rates, and reduced costs, while low cost and long lead times mean oil price changes are less important and don't affect utilization or rates.

• Contract practice. Large numbers of rigs mean many contracts expiring, likely to be bid at new prices, while reliance on long-term contracts means fewer expirations and stickier prices.

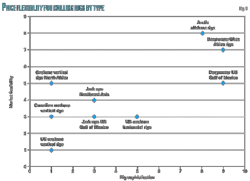

To that end, a rough judgment has been made about the different types and locations for drilling rigs to suggest how responsive their rates will be. In Fig. 5, these are depicted graphically, with the rigs in the upper right being the least price-inelastic and the rigs at the lower left the most price-elastic. Empirical work to test this is left for a future date.

Escalation cyclical

The bulk of recent cost escalation appears to be cyclical and should not be expected to continue in the longer term.

Factor inputs like steel and cement are likely to remain relatively close to historical means, which will lower development costs significantly. Specialized labor and rates for drilling rig rentals will reflect demand to a much greater extent and the degree of fungibility of the type of equipment: The more specialized the equipment, the stickier the prices, and the more flexible a market, the more volatile the price.

Most important, in the long run, higher costs appear unlikely to provide a support for higher prices, and the argument that a price of about $70/bbl is a new "floor" price due to high marginal costs does not appear to be valid. Since many in the industry appear to be anticipating a floor price somewhere near $70/bbl, it is likely that lower prices will cause economic hardship for the industry as in the mid-1980s.

The precise path for prices will be determined by a complex interplay of economic growth, upstream investment, geopolitical developments, and OPEC behavior. However, it appears that many in the industry are now, as in the early 1980s, making rationalizations to explain their optimistic price forecasts.

The author

Lynch earlier was vice-president of oil services at WEFA Inc., director, Asian Energy and Security, at the Center for International Studies, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and a lecturer in the Diplomatic Training Program at the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy, Tufts University, and a lecturer at Vienna University. He also has held research positions at MIT.

More Oil & Gas Journal Current Issue Articles

More Oil & Gas Journal Archives Issue Articles

View Oil and Gas Articles on PennEnergy.com