Sliding Japanese product demand to accelerate

Since 2008, the speed and degree of Japan's petroleum product demand decline has accelerated in light of the global economic recession. Consequently, the Japanese economy posted a 5.2% contraction (on a preliminary basis) in gross domestic product for 2009.

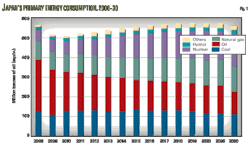

Primary energy consumption (PEC) fell nearly 10% year-on-year in 2009. Consumption of oil, natural gas, and coal in the primary energy mix all declined YOY. Only nuclear increased from 2008 after Tokyo Electric Power Co. restarted two units at the troubled Kashiwazaki-Kariwa 8.2-gw nuclear power plant—Japan's largest.

Petroleum product demand fell by 8.5% to nearly 4.2 million b/d in 2009 YOY, following a 4.5% YOY decline in 2008. Gasoline was the only product to increase in demand in 2009 (0.6% YOY) helped by government economic stimulus measures. Fuel oil demand was the worst hit (–28.4% YOY) as a result of slack production and reduced power demand.

Total power generation fell by 8% YOY in 2009. Japan's refining output declined by 7.8% to nearly 3.6 million b/d in 2009. Product imports also declined to 866,000 b/d from 970,000 b/d a year earlier, while product exports totaled 369,000 b/d, similar to 2008.

These are some of the major findings by the East-West Center, Honolulu, in a report released last month.

For the long term, Japan's oil product demand will decline for four reasons:

1. An aging and shrinking population and thus a declining productive population.

2. Which leads to a changing lifestyle and industrial structure.

3. Stringent energy efficiency and conservation regulations.

4. Weak consumer spending and corporate investment, leading to only modest economic growth.

Product exports will slow due to the region's product surplus amid squeezed margins. Exports of gas oil, which currently account for most exports, will fall to 178,000 b/d in 2010 and 101,000 b/d in 2015.

Crude throughput is likely to fall further, by 4.1% in 2010, to less than 3.5 million b/d, after an 8.1% decline in 2009. Consequently, crude imports for 2010 will likely fall to 3.5 million b/d, from 3.65 million b/d in 2009. For 2015, crude throughput will fall to 2.98 million b/d, wherein crude imports are to fall to some 3 million b/d.

Facing serious demand deterioration and resulting excess capacity, Japanese refiners announced plans to close at least 820,000 b/d of refining capacity by early 2014. Actual crude-distillation-unit (CDU) closures will likely total 1.2-1.3 million b/d because the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry informed refiners of its ordinance in April—under the law entitled Sophisticated Methods of Energy Supply Structures—stating that the cracking/CDU ratio in refineries must be 13% or higher by March 2014.

METI's official intention is to increase Japanese refineries' competitiveness in the international markets. In fact, the ordinance will effectively lead to more refining capacity closures as refiners will unlikely be able to justify investment in upgrading all of their refineries under the current business environment and stagnant future.

As are many in the industry, the author was skeptical the law would allow METI to have such authority, considering it is against the direction of industry decontrol. But in fact METI's requirements are binding. Refiners seem to have no option but to comply.

This report presents Japan's latest energy-demand outlook for 2030, as well an analysis of Japan's energy policy and its implications for Japan's energy companies. Special emphasis is given to METI's ordinance in April 2010, which will change the overall picture of Japan's refining industry by March 2014.

Energy policy

The future of the Japanese economy does not seem rosy, faced as it is with massive government debt, a contracting productive population, increasing public awareness of global warming, and such. Given that consumer spending and corporate investment are likely to remain weak, only modest economic growth can be forecast for the medium to longer term (around 1-2%/year GDP growth).

The government's energy policy will substantially affect Japan's economic and industrial activities for the medium and long term. As far as energy demand is concerned, Japan's energy policy will continue to focus on moving away from oil and other fossil fuels and reducing greenhouse-gas emissions. This is especially the case for the power sector, in which nuclear power generation is encouraged and petroleum demand is to decline.

Under the unrealistic climate policy goals of the currently ruling Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ), Japan would reduce its GHG emissions by 25% by 2020 from 1990 levels. This is much tougher than the previous goal set by the Liberal Democratic Party, which proposed an 8% cut by 2020 compared with the level in 1990.

The author believes such unrealistic reduction targets are not achievable, and the government will eventually have to lower Japan's GHG-reduction targets. From the beginning, the DPJ made Japan's international pledge with the proviso that all major GHG-emitter nations agree to appropriate reduction targets, certainly having left much room for Japan to make further downward revisions in its pledge.

If the DPJ officially maintains such unrealistic emissions targets, Japan's economic growth will suffer greatly, as these targets could force manufacturing industries to relocate production overseas—leading to a hollowing out—and aggravate unemployment. Consumer spending will be drastically hampered.

What must be noted is the uncertainty over how long the current DPJ-led administration will last as Japan's ruling party, considering the recent resignation of Prime Minister Hatoyama after only 8 months in office. His resignation came as a result of a funding scandal and his failure to keep a campaign manifesto to move a US Marine base from Okinawa.

The Hatoyama administration also failed to put together comprehensive and concrete measures to achieve economic growth, despite the fact that Japan faces several serious issues, such as a declining and aging population, a declining productive population, a high unemployment rate, widening income disparity, and building national debt.

Primary energy consumption

Japan's primary energy consumption fell nearly 10% YOY in 2009, primarily as a result of the economic recession (Fig. 1). On a preliminary basis, oil continued to lose its share, although it still dominated the nation's PEC at 46% (down from 47% in 2008). Coal accounted for 21% (down from 23%), and the share of hydro remained unchanged at 3%.

The share of natural gas increased to 18% from 17% in 2008 and nuclear energy's contribution increased to 12% from 10% in 2008. Two of the seven nuclear units at TEPCO's Kashiwazaki-Kariwa plant resumed operation in 2009, thereby contributing to raising Japan's overall nuclear power utilization.

In the long run, the role of oil in Japan's PEC will continue falling, particularly as the DPJ-led administration's target is already discouraging Japan's manufacturing industry from investing in the domestic market for the medium to long term.

Also in the power sector, nuclear power generation is highly encouraged but petroleum demand (both fuel oil and crude oil) will decline into the future. In the meantime, the use of natural gas will increase. As such, nuclear power and natural gas will be the major sources to sustain Japan's PEC growth by 2030.

Affected mainly by oil, Japan's PEC is likely to decline again in 2010 but rebound for 2011. In the longer term, as Fig. 1 shows, PEC as a whole will start declining toward the end of this decade in light of Japan's looming fundamental structural changes: shrinking population, strict energy conservation policies, and greater efficiency regulations.

Product demand

Following a 4.5% YOY decline in demand for 2008, Japan's petroleum product demand fell by 8.5% in 2009, inclusive of demand for bonded bunker and jet fuels. Gasoline was the only product that posted an increase in demand—although it was limited to 0.6%—helped by government measures.

Effective the end of March 2009, the maximum toll for passenger cars that are equipped with an Electronic Toll Collector device on expressways across Japan was reduced to ¥1,000 (about $11) for unlimited distances on weekends and holidays, as part of economic stimulus measures.

Demand for fuel oil was worst hit, down by 28.4% YOY, as a result of slack production and reduced power demand. Total power generation fell by 8% YOY in 2009 to 910 terawatt-hr (tw-hr). The industrial sector was hit hardest due to stagnant production.

Accordingly, fuel demand for thermal power generation (i.e., crude oil, fuel oil, coal, and LNG) declined. Crude oil consumption for direct burning fell to 66,000 b/d in 2009 compared with 188,000 b/d in 2008, while low-sulfur fuel oil consumption fell to 108,000 b/d in 2009 from 208,000 b/d a year earlier (Table 1).

On the other hand, base-load nuclear power generation increased by more than 7% YOY, although utilization rates throughout 2009 remained much lower than 85%—the level the government hopes utilities maintain (Table 2).

For 2010, the Japanese economy will likely grow by nearly 1.0%, but the author expects petroleum product demand to continue to shrink due to lingering weak consumer spending and stagnant production. Accordingly, Japan's petroleum product demand is likely to fall by a further 5.3% in 2010.

Government's measures on tax and highway tolls are critical in determining its petroleum product demand. If existing highway toll discounts—applicable to ETC-equipped cars for weekends only—are expanded to all cars (even without ETC devices) and to weekdays, gasoline demand could grow after 2009.

Otherwise, gasoline demand will fall by 4% YOY, especially since the DPJ-led administration already decided not to implement its key political pledge to simply abolish the provisional gasoline tax (¥25/l.).

Instead, the government has put together a complicated scheme that would abolish the provisional gasoline tax only if the pump price of regular gasoline exceeds ¥160/l. for 3 consecutive months.

For the longer term, overall demand will continue falling, due mainly to such structural factors as an aging and shrinking population and changing lifestyle and industrial structure. Japan will shift its focus on tertiary industries, thereby moving away from heavy industries, partly due to more stringent restrictions on carbon dioxide emissions.

Overall, total petroleum product demand will be down to around 3.2 million b/d by 2020 and fall to less than 3 million b/d by 2030 (Fig. 2).

By product, the industry's cash-cow has always been gasoline, but its demand will continue declining under the government's effort to promote alternative fuels, such as hybrid, fuel cell, and electric vehicles. The government hopes that by 2020, 70% of new car sales will be of those using alternative fuels and that this will reduce gasoline demand sharply.

Heating fuels—such as kerosine and Type-A fuel oil—will be switched to electricity and city gas, except for the core demand in northern districts (e.g., Hokkaido, which consumes kerosine in winter for home heating). Road transportation (by trucks) will also be rationalized, together with the improvement of fuel efficiency of heavy trucks. Thus diesel demand will be reduced.

Industrial fuel demand will continue to fall, while fuel oil and crude oil demand for power generation will see a similar trend. The only product likely to increase is jet fuel, due to an expected increase in domestic and international flights.

Product balances

Japan's 2009 refinery output declined by 7.8% to about 3.6 million b/d, as the global economic recession accelerated both the speed and degree of Japan's demand contraction. Demand for industrial fuels generally deteriorated. Furthermore, falling power demand and increasing nuclear power generation in 2009 made electric utilities reduce fuel oil and crude oil consumption.

Accordingly, overall product imports declined to 866,000 b/d from 970,000 b/d in 2008, while product exports totaled 369,000 b/d, similar to 2008, with gas oil exports totaling 215,000 b/d (Table 3).

Bioethanol (in the form of ethyl tertiary-butyl ether) blending into gasoline started on a trial basis in 2007. Commercial sales of biogasoline began in 2009 and E0.7 (0.7% ethanol) biogasoline is being sold at gasoline stations this year. METI may require E2.7 (2.7% ethanol) gasoline by as early as 2017-18.

Japan will remain dependent on naphtha and LPG imports. Small imports for other products listed in the table will take place in order to meet the supply-demand balances. We believe that product exports, on the other hand, will further wane due to the region's product surplus situation amidst squeezed margins.

Exports of gas oil, which currently account for most exports, will fall to 178,000 b/d in 2010 and further to 101,000 b/d in 2015. Fuel oil will likely be placed into the marine bunker market as needed, but excess supplies may need to be exported regardless of their margin levels.

After an 8.1% decline in 2009, Japan's crude throughput will fall by a further 4.1% in 2010 to nearly 3.48 million b/d. Consequently, Japan's crude imports for 2010 are expected to fall to 3.5 million b/d, from 3.65 million b/d in 2009. For the medium to long-term, crude throughput will likely fall to about 2.98 million b/d in 2015, wherein crude imports are to fall to 3 million b/d.

Planned reductions

Since yearend 2009, Japan's leading oil refiners—Nippon Oil jointly with Nippon Mining Holdings, Showa Shell, Cosmo Oil, and Idemitsu Kosan—have announced a series of refinery closure plans (Table 4).

As of January 2010, Japan had a total refining capacity of 4.8 million b/d. But some of the capacity closures by Cosmo Oil had already taken place during first-quarter 2010 and thereby reduced Japan's capacity by 80,000 b/d.

Cosmo Oil officially notified METI of the changes, with reductions in crude distillation capacities at the Chiba (–20,000 b/d), Sakaide (–30,000 b/d), and Yokkaichi (–50,000 b/d) refineries, while increasing the Sakai crude capacity by 20,000 b/d. Sakai's capacity was increased because the company now has a new 25,000 b/d coker, which started commercial operation in April 2010.

As of July 1, 2010, Nippon Oil and Nippon Mining Holdings will form JX Nippon Oil & Energy Corp., a wholly-owned refining and marketing company of JX Holdings Inc., which was established on Apr. 1, 2010, as a holding company. It will jointly close as much as 600,000 b/d of refining capacity by March 2014, the latest.

Under the first phase, JX Nippon Oil and Energy Corp. will reduce its refining capacity by 400,000 b/d by Mar. 31, 2011. The reductions will come from Negishi, Mizushima, Oita, and Kashima, as listed in Table 3. In addition, Nippon Oil's Toyama refinery—which had closed in March 2009—was included in the consolidation plans.

Under the second phase, JX Nippon Oil and Energy plans to close another 200,000 b/d by Mar. 31, 2014, but details of the second set of reduction plans had not been announced at the end of May. Table 4 includes the Osaka refinery (115,000 b/d) as a possible candidate to be closed, if the company's plan to own the refinery jointly with China National Petroleum Corp. does not materialize. Currently, the plan is to turn the Osaka refinery into an export-oriented refinery, as CNPC is believed to be considering marketing all the products from the refinery if this JV refinery project moves ahead.

Showa Shell announced that it will close the Keihin Ohgimachi refinery (120,000 b/d) after September 2011. The refinery has been operated by Toa Oil, Showa Shell's affiliate, together with Toa's Mizue CDU as one integrated refinery. The company expects rationalization of the refineries will enhance Toa's competitiveness. The Ohgimachi and Mizue refineries are connected with pipelines for exchanging feedstock.

After the Ohgimachi refinery closure, Mizue's 27,000-b/d flexicoker is to remain fully operational. The company will continue receiving vacuum-residue feedstock from Tonen General's Kawasaki refinery, while Toa supplies naphtha to Tonen General for its petrochemical production.

Toa Oil's Keihin and Tonen General's Kawasaki are both in the government-sponsored operational integration program called the Industrial Complex Renaissance and will further enhance efficiency by increasing feedstock exchanges.

The most recent development is Idemitsu Kosan's announcement in April that it will reduce a total crude capacity of 100,000 b/d by fiscal yearend 2014.

METI's ordinance

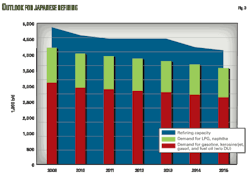

In all, by early 2014 at least 820,000 b/d of refining capacity will be closed, based on plans that could be identified. Fig. 3 illustrates Japan's refining capacities to 2015, which incorporates the 820,000 b/d of closures, and my petroleum product demand outlook to corresponding years. The gap between refining capacity and demand illustrates Japan's surplus refining capacity.

Furthermore, we have separated demand for LPG and naphtha from the rest of demand, as Japan's refining industry was originally designed mostly to import these two products. For example, domestic production of LPG and naphtha accounted for 4% and 10% of their respective total demand in 2009. Thereby, Japan imported 371,000 b/d of LPG of the total demand of 473,000 b/d and 409,000 b/d of naphtha of the total demand of 755,000 b/d in 2009.

Fig. 3 illustrates that—either including or excluding LPG and naphtha demand—Japan will still have excess capacity even with the 820,000 b/d of refinery closures.

Beyond those capacity-disposal plans announced (Table 4), we are now certain that more crude capacity closures will occur by March 2014. Total closures will therefore likely be 1.2-1.3 million b/d by March 2014.

In April, METI informed refiners of the ordinance (under the law entitled Sophisticated Methods of Energy Supply Structures) stating that refiners should meet the cracking/CDU capacity ratio of 13% or higher by March 2014.1

METI has set forth guidelines for refiners to meet this ratio. For example, a refinery with a cracking/CDU ratio of less than 10% (at present) must improve this ratio by at least 45% in order to achieve the required cracking/CDU ratio of 13%.

Officially METI's intention is to increase Japanese refineries' competitiveness in international markets, since METI believes Japan's cracking/CDU ratio is lower than other key countries (e.g., Asian and European countries, and the US).

The reality, however, is that the ordinance will effectively lead to closings among those refiners that do not meet the ratio of 13% today, as refiners will unlikely be able to justify the investment to upgrade all of their refineries under the current business environment and stagnant future.

Therefore, in order to abide by METI's ordinance, refiners should close their refineries or abolish crude units that are not "sufficiently" supported by cracking units. By fourth-quarter 2010, we believe the plans—whether to invest in refineries to upgrade or to close down refineries—by each refiner will be put in place.

METI's radical measures and the fact that the law should allow METI to have such authority—when it is against the direction of industry decontrol—took many in the industry by surprise. But the fact is that METI's requirements are binding, and refiners seem to have no option but to comply with them. It is clear that by March 2014 the picture of Japan's refining sector will have changed drastically.

Japanese refiners will now need to transform, as fast as possible, to integrated energy companies from oil refiners and wholesalers by diversifying their businesses. Such new businesses include LNG import and wholesale, gas and power, new energy, and overseas upstream and downstream.

Reference

1. METI's cracking/CDU ratio is calculated on resid fluid catalytic cracker, coker, and resid hydrocracker.

The author

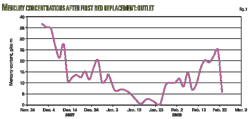

Correction Throughout "Gas plant solves Hg problems with copper-sulfate absorbent" by Omar M. Baageel (OGJ, May 24, 2010, p. 51), "g/cu m" should have read "ng/cu m," nanograms/cubic meter. |

More Oil & Gas Journal Current Issue Articles

More Oil & Gas Journal Archives Issue Articles

View Oil and Gas Articles on PennEnergy.com