While every long-term asset play begins life as a start-up, not every start-up succeeds in becoming a sustainable long-term asset. Deciding when to build the culture, processes, systems, and practices that will support operations excellence is critical.

In late 2007, ConocoPhillips Canada (CPC) began production at its 27,000 boe/d-capacity Surmont steam assisted gravity drainage (SAGD) oil sands operation. A 50-50 joint venture with Total operated by CPC, this operation, 40 miles south of Fort McMurray, Alta., represents a strategic investment for ConocoPhillips, one of the largest leaseholders of deep oil sands with a long-term vision of becoming a leading oil sands producer. Plans for a second phase of Surmont were under way at Phase 1 start-up, bringing forecasted gross daily production to 110,000 boe/d when both phases reach full production capacity.

During the first phase, operational quality was crucial if Surmont was to become a viable asset and provide near-term corporate benefit. Just as significant, however, was the need to build confidence in and capability of CPC's SAGD operations for long-term growth. Clearly, any decision about future investment depended on the sustained success of this initial phase of operation. To accelerate the delivery of value and development of capability simultaneously, in early 2008 CPC designed an operations excellence program, called Simply the Best, that the operations team implemented from May 2008 to June 2009, with support from the implementation consultancy Evolve Partners LLP.

The foundation

The first step was to engage the leadership team and wider organization in the vision and plan for improvement. The leadership team first focused on the long-range strategic vision of being a top oil sands producer then broke that down into nearer-term goals to which people could relate more directly. The team also established a clear set of "exit-rate goals" for 2009 to establish the priorities for operations excellence implementation and create the desire in the organization for performance improvement.

These goals were translated into specific performance objectives for teams and individuals, along with clarification of roles and accountabilities.

The team recognized that it would need to enroll people in the change effort in a way that was different from past communications efforts. Its members decided to rely on simple visual graphics, easy-to-understand language, and equally simple and straightforward "business basics" lessons with plant operators in two-way communications sessions at the plant.

One of the concepts that engaged people was that the program was about removing sources of frustration—the issues that kept them from doing the things they wanted to do. The leadership team listened to people to understand operational frustrations and designed the program to remove the highest-impact frustrations.

With the vision articulated and communicated in a way that allowed each individual to understand his or her role in the operation, the next step was to engage the wider organization in taking an honest look at current performance and specific areas for improvement. To achieve this, a wide cross-section of the organization participated in on-line surveys and one-on-one interviews. Through workshops and data analysis, people had the opportunity to examine performance in new ways, identify ways of improving it, and share it with the leadership team.

Studies included mapping key processes such as planning, conducting "day-in-the-life-of studies" to understand wrench-time productivity and how effectively people used their time, and discerning trends in data. These studies were conducted by the relevant ConocoPhillips personnel themselves so that they could understand their own operations better and focus on what was necessary to achieve operations excellence.

One of the challenges the implementation team faced was that everything was important—there were too many opportunities and activities, and everything felt like it needed to be done at once. Working through the foundational process allowed the team to become more ruthless in setting priorities and focused on near-term activities. The outcome of the initial foundation process was a clear implementation program with results, milestones, themes, roles, and action plans.

Implementation keys

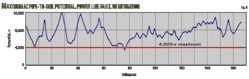

Key areas of focus for the program implementation, the progression of which is shown in Fig. 1, included:

• Implementation of a robust management system across senior management, engineering, and operations that included shift handovers, daily production meetings, daily planning meetings, and weekly, monthly, and quarterly leadership team meetings.

• Application of regular formal and informal one-to-one coaching to over 20 team members across senior management, engineering, and operations.

• Implementation of greatly improved processes across safety, product quality, lost production opportunity, scheduling, master service agreements, training, and fuel gas efficiency.

• Renewed focus on key performance indicators and results.

• Development of a culture of clear accountability by building awareness of performance at all levels and helping people take actions to improve operation themselves.

• Introduction and reinforcement of a common language and set of tools around performance, including "5 Whys" and how to make action-oriented requests of others.

Focusing on the need to deliver short-term results as an opportunity to build long-term capability, the program did not strive to drive in new processes and systems and seek compliance; instead, it tried to educate people as to the purpose behind the new ways of working. Although there were some team exercises and training interventions, most of this education occurred through one-on-one coaching and through practical meetings and workshops in which teams worked together on solving specific issues.

Through this approach, personnel learned about continuous improvement and problem-solving. This, combined with selective recruitment of experienced professionals into key roles, massively increased the "bench strength"—depth of skill and experience—of the organization.

Matt Fox, CPC president at the time of this program, observed, "We have a better organization as a result of the program, and I have greater confidence in our ability to solve new problems."

Personal learning

The critical aspect of effective implementation programs is "supplantive learning"—i.e., achieving a permanent transformation of mindsets, behaviors, and capabilities by using specific experiences to supplant old ways of doing things with new ways.

Fig. 2 shows an example of this learning for one key member of the team. Another example of supplantive learning was expressed by a production engineer who said, "I never liked to plan, and now I won't work without one."

Delivering results

Overall, the Simply the Best program delivered the following benefits:

• Step change in safety performance.

• Supported 60% SAGD production ramp-up.

• 21% increase in operating efficiency.

• 12% increase in fuel gas efficiency.

• 10% reduction in unit cost.

• Elimination of off-specification product.

When the Simply the Best program began in May 2008, the oil price was $120/bbl and on its way to over $140/bbl. This created three levels of urgency for the program.

The first was opportunity cost. A slower pace of operations excellence development would deny the project revenue enhancements available in a period of elevated prices.

The second level of urgency was direct cost. The Surmont SAGD operation requires diluent, light crude that is blended with the bitumen to meet pipeline specifications. Insufficient diluent leads to off-specification product, but overdiluting is a costly giveaway. Value thus can be captured from achieving narrow tolerances on diluents usage.

The third level of urgency was organizational. The run-up in prices stimulated investment in oil sands and other parts of the industry and intensified competition for resources. Creating an operational excellence culture is a compelling employment value proposition.

The Simply the Best program boosted profitability for ConocoPhillips by accelerating the ramp up of production, thereby allowing the operation to capture benefits of the oil-price bubble. At the same time, better process controls and systems around product quality eliminated off-specification product while achieving much tighter tolerances on dilution. The combination of the increased production and reduced crude use together contributed well over $100 million in benefits over a 6-month period.

A decline in oil prices in the latter half of 2008 presented a new urgency related to the ability to operate on a tight margin. Again, the program delivered benefit by maintaining the production and diluent benefits while removing waste in operations.

The new management systems, clear roles and responsibilities, and leadership behaviors that were introduced over the course of the program allowed the leadership team, and the extended leadership, to work together to refocus on cost and maximize cash flow. One leader said, "Everything we've done over the last 6 months has prepared us to deal with this crisis."

Beyond these short-term accomplishments, the program delivered strategic value by demonstrating CPC's ability to be an effective oil sands operator and building the confidence, capability, capacity, and culture for future growth.

Insights

Key insights from the Simply the Best experience that are applicable to other similar operations excellence implementation programs include:

• Focus on vision and results. Simply the Best was a results-driven program, with a clear business case aligned to an overall organizational vision. This was important because it gave real urgency and need to learn and adopt new ways of working while connecting those changes to a larger purpose that everyone could understand.

• Engage the front line. The program placed heavy emphasis, particularly at the beginning, on working directly with the front line—workers directly involved in operations—and changing processes, systems, and behaviors where value is created. Importantly, the implementation team was able to engage the front line as implementation partners with genuine exploration of people's ideas and concerns to build ownership.

• Engage the leadership. The program also worked on aligning leaders and encouraging leadership to promote the program and reinforce desired behaviors. For example, the leadership team spent much time in the field working directly on safety issues and role modeling behaviors around accountability.

• Blend the "hard" and "soft" skills. The core focus of Simply the Best was operations excellence, and much of the work done in the program focused on "hard" technical issues such as maintenance and reliability, process improvement, and key performance indicators. Just as important to the success of the program was a continuing focus on "soft" issues such as leadership and overcoming resistance to change. Many of those soft skills were critical success factors for the business.

• Provide dedicated internal resources. The implementation team consisted of full-time dedicated ConocoPhillips personnel who were recruited from the line to work as internal change agents. This team was supported by the external consultants. Having an internal team ensured that the program was internally owned and had the look and feel of an internal effort, not an external one. Members of the dedicated internal team also were able to accelerate their learning and development, attaining levels of capability and performance that were beyond even their own aspirations.

Moving from status as a newcomer to that of a long-term operator in the oil sands is difficult. The technical issues are challenging enough without the behavioral, systemic, and process changes that are needed.

Building operations excellence into the asset from the start is the surest way to maximize present value from the operation and is an insurance policy against losses in the future.

The authors

Perry Berkenpas is ConocoPhillips Canada's vice-president, oil sands operations, with responsibilities that include the Surmont project, the company's first operated steam-assisted gravity drainage project. Before ConocoPhillips Canada, he worked for Gulf Canada and Imperial Oil. Berkenpas grew up and received his education in Vancouver, BC.

Greg Bussing is ConocoPhillips Canada's operations support and operations excellence manager for oil sands. He joined the company in 1987 as an engineer with Conoco Pipeline and has held positions in operations, engineering, marketing and sales, and business strategy in the US and Canada. Bussing holds a BS in industrial engineering from Kansas State University.

Seth D. Tyler is a partner with Evolve Partners, a Houston implementation consulting firm specializing in operational excellence in the oil and gas and chemical industries. He joined Evolve in 2002 and has more than 15 years of management consulting experience. Tyler holds a BA from Tufts University and a master of public affairs degree from Indiana University.

More Oil & Gas Journal Current Issue Articles

More Oil & Gas Journal Archives Issue Articles

View Oil and Gas Articles on PennEnergy.com