Davy Jones discovery opens up new large production potential

The recent Davy Jones gas discovery in the Gulf of Mexico is a perfect example of the dynamics and drama associated with frontier exploration.

Even under ordinary conditions the exploration business is capital and technology intensive with huge risks. But frontier exploration is in a league of its own where various conditions are by definition not ordinary.

On Jan. 11, 2010, McMoRan Exploration Co. (MMR) announced a giant gas discovery in its deep Wilcox test well on South Marsh Island Block 230 in 20 ft of water and 10 miles off Louisiana. MMR spud the well on June 28, 2009, and logged it in January 2010.

The discovery is notable for several reasons.

First of all, making a world-class discovery in the heart of the US oil patch is rare in this day and age. To date nearly 4.5 million wells have been drilled in the US compared with only 1.5 million in the remainder of the world. The Davy Jones discovery, therefore, was made in the heart of one of the most mature provinces in the world.

The average discovery worldwide these days contains only about 50 million bbl of recoverable reserves (or the equivalent). The Davy Jones discovery likely will have an order of magnitude more.

One of the most frustrating things for explorers in the international sector is to make a big gas discovery in a remote location that has no market for gas and no infrastructure. Explorers would often get a far off look in their eye and wonder: "Imagine how valuable this discovery would be if it was on the US Gulf Coast!"

The Davy Jones discovery provides an excellent insight into this issue of value. Our base case economic analysis for the Davy Jones discovery, based on public data, uses 2.5 tcf of recoverable reserves, equal to 400 million boe, based on a conversion factor of 6 Mcf/bbl.

Secondly the discovery was not made in a known, established play. The MMR discovery opened up a whole new province where MMR holds a large acreage position. MMR has one of the largest acreage positions in the Gulf Coast region with rights to about 1 million gross acres including 150,000 gross acres associated with the ultradeep subsalt gas play.

By world standards, 150,000 acres may not sound like much. Typically a single block in the international sector can be from 0.5 to 1 million acres and for a frontier block, 3 million acres or more.

But by US standards the MMR acreage in the now proved deep Wilcox trend is important. The discovery opens up prospects throughout the gulf region from onshore to the deepwater gulf. MMR reportedly has another 12 prospects in the Davy Jones trend.

Third the technical aspects of the Davy Jones discovery are stunning. Water depth is only 20 ft but the Wilcox reservoirs along this trend are from 25,000 to more than 30,000 ft deep.

Ballpark drilling costs reported by MMR, are about $100 million with completion costs of $50-75 million. This is partly due to high temperatures and extremely high pressures.

Our analysis

The Davy Jones story captures much of the dynamics, risks, and drama associated with the oil and gas industry. And it is fortunate that MMR provided so much information.

Often, discoveries like this are treated as state secrets. Or, press releases do not allow sufficient information to perform an analysis such as undertaken in this article. The information we used was gleaned from various sources and required a modest amount of research.

The discovery also provided insight into recent industry discussions about disclosure and transparency as well as reserve reporting. While the US Securities Exchange Commission for years would not allow companies to book barrels without a flow test, the financial market made a clear statement about that with this, yet untested, discovery.

Davy Jones provides fresh new perspective on similar geological provinces worldwide. Just as industry now is scouring the world for more shale gas, as it once did for coalbed methane, it now will review deeper plays with a new appreciation.

Unfortunately, in spite of the clear and intense risks undertaken by the Davy Jones partners and others like ExxonMobil Corp. that have worked this trend, governments rarely remember these aspects of a discovery.

Just as this discovery is making headlines, the US government is aggressively seeking ways to increase taxes particularly on the oil industry. The terms at the moment for a Davy Jones's development are fair considering the costs, and risks. But ventures in the deep Wilcox will be sensitive to tax rates.

Blackbeard

The Blackbeard prospect is an earlier attempt to test the deep Wilcox. It was drilled to 30,067 ft and abandoned in 2006 by ExxonMobil. The company abandoned Blackbeard partially because of high drilling costs and risks associated with the extreme high pressures and temperatures in the deeper sections. ExxonMobil reportedly spent more than $200 million on the well before departing.1

MMR subsequently acquired the rights to the Blackbeard prospect and other Gulf Coast properties in a $1.1 billion acquisition from Newfield Exploration Co. in August 2007. MMR then reentered the Blackbeard well and deepened it to 33,000 ft, but that was still short of reaching the Wilcox formation.

MMR believes the correlation between Davy Jones and deepwater Wilcox production bodes well for the Blackbeard prospect. The Blackbeard and Davy Jones wells are the only two control points on the shelf that have tested the Lower Wilcox trend. Paleontology data in the form of microfossils at different intervals in the Lower Wilcox have confirmed the correlation.

Because of the nature of the province and the highest drilling density of any offshore province in the world, the paleo data are well understood and documented. Detailed correlations are possible across large distances from onshore to the deepwater.

MMR also intends to test the deeper Lower Wilcox (Eocene-Paleocene) Whopper sand and the Upper Cretaceous Tuscaloosa sandstone, which are prolific producers further north onshore and to the south in the deepwater.

The cross-section in Fig. 1 illustrates the position of the trend. The Davy Jones well is 85 miles south of the nearest deep Wilcox production near Baton Rouge, La., and 170 miles north of deepwater discoveries in Lower Tertiary reservoirs that include Shenandoah, Kaskida, Tiber, Tahiti, Jack, and Cascade. Tuscaloosa sands north of Baton Rouge are cleaner sands with thicknesses of 300-500 ft.

Market value

Following MMR's January announcement of the discovery, its stock price jumped to about $15/share from about $8/share, during the preceding months. The $7/share increase for 86 million shares represents a market value for the news of $602 million for MMR's 32.7% working interest. Little else was happening in the market or with MMR at the time that could justify the change.

Thus, the imputed value for 100% of the working interest is $1.841 billion.

The natural question is: Is this a reasonable value for undeveloped reserves in the deep Wilcox?

Beyond the discovery itself, by proving up this play concept MMR has an acreage position of 150,000 gross acres in this ultradeep subsalt gas play. The importance of this is lost on no one, but it is difficult to tell how much this factors into the market response seen in mid-January.

The factors that most affect the value of the discovery are expected recoverable reserves, product prices, costs, fiscal terms, and discount rate.

Expected recoverable reserves

The Davy Jones structure (Fig. 2) is a relatively simple dome-shaped anticline indicated by seismic data. The discovery well reportedly has proven up 7,000 acres of productive area in Upper Wilcox (Paleocene-Eocene) sandstones based on the lowest known hydrocarbons from the discovery well.

The structure as depicted in published maps has a 3-mile diameter and is in the center of four 5,000-acre blocks. If the structure is full to the spill point, the productive area could approach 18,000-20,000 acres.

The planned Davy Jones appraisal well is 2.5 miles southwest of the discovery well. As shown in Fig. 3, it will test the same zones, expected to be 1,000 ft shallower. The expectation also is that it will test the Upper Cretaceous (Tuscaloosa).

MMR has reported 200 ft of net reservoir sands in six separate intervals. The company initially had reported 135 ft of reservoir sands in four separate intervals, but further drilling and logging added two more pay zones with 65 ft of net sand. All reservoirs appear to be hydrocarbon bearing and full to the base of the sands in the discovery well.

Reported pressures are about 25,000 psi at depths of 28,100 ft. This is consistent with a pressure gradient of about 0.89 psi/ft. This gradient is nearly twice as high as normal hydrostatic pressure, which typically in the Gulf Coast is about 0.465 psi/ft.

This gradient is higher than a normal 0.433 psi/ft freshwater gradient because of the high salinity content of Gulf Coast formation waters.

The implications are huge. These pressures require drilling fluid weights more than 17 ppg just to balance reservoir pressures let alone keep things under control. MMR reports drilling with 18.2-18.6 ppg mud.

This technical requirement is demanding and expensive particularly at high temperatures found in deep reservoirs. At high temperatures mud properties break down, particularly viscosity. Maintaining drilling fluid integrity and pressures is critical in any drilling situation but especially in reservoirs like these. The cost of drilling fluid alone could exceed $30 million/well.

The higher pressures also mean more gas.

Reported bottomhole temperatures in the deep Wilcox are from 420° to 480° F. Assuming a mean annual surface temperature of 70° F./year, the temperature gradient is about 1.3° F./100 ft.

Above 400° F., normal electronic components for measuring-while-drilling or normal logging operations deteriorate rapidly, and holding calibration can be problematic. MMR reported drifting on the logs due to the high temperatures.

Porosities have been reported from 13% to as high as 20%. This has surprised some geologists who have not expected such high porosities at these depths. MMR reports that its logs indicate some of the highest quality Wilcox sands seen in the gulf region.

In one sand, about 50 ft thick, MMR reported a classic gas effect (crossover) from the neutron-density porosity logs. But MMR has pointed out that some drifting observed on the neutron log in particular needs recalibration. Also, the amount of crossover in porosity units would be helpful to know but MMR has not reported this yet. Anything more than six porosity units (for example where density may indicate 14% porosity while the neutron indicates 20%) is important.

Although MMR has yet to flow test the well, it has reported the reservoir zones have up to 10-20 ohms of resistivity. In many parts of the world, this measure would have little meaning. In the Gulf Coast (and other parts of the gulf), formation waters are so saline that any resistivity greater than 1.5 ohms in reservoir quality rock signifies that a zone likely is hydrocarbon bearing.

MMR has explained that some logs need careful recalibration to account for the high temperatures. It reported drifting on some log curves due high temperatures, and at least one resistivity tool failed while logging. This tool was described as having burned up.

Typically electronics can withstand the high temperatures for short periods but at such depths, it is difficult to get the equipment in and out quickly and this is particularly true of pipe-conveyed logging tools as compared with wireline tools.

The $600 million financial market response to the discovery shows the importance of the resistivity information. More than anything else, this otherwise obscure piece of information effectively replaced a flow test as far as the financial market was concerned.

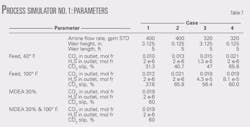

Not long ago, there was considerable debate between the US industry and SEC engineers about deepwater gulf reservoirs and the prospect of booking barrels in the absence of highly expensive flow tests. But only the highest deepwater drilling costs around the world compare with the cost of drilling a well in the deep Wilcox trend. Rarely has so much hinged on the results of a deep resistivity log. Much of the argument justifying booking barrels in the US without flow tests centered on the importance of the deep resistivity measurements. Our analysis, based on the information available in early March 2010, indicates a most likely recoverable reserve of 2.5 tcf of gas for the field. Table 1 summarizes the assumptions we used in our volumetric analysis.

Expected production from the wells is about 100-125 MMcfd with ultimate recovery of more than 100 bcf/well. This is fairly easy to imagine. Of the roughly 50 or so gas discoveries reported each year around the world, the average test rates are about 20 MMcfd. With the Davy Jones reservoir thickness and pressures, 100+ MMcfd sounds reasonable.

Product prices

Our analysis assumes that Davy Jones will produce dry gas with 0.65 sp. gr. By some definitions dry gas means a liquid yield of less than 10 bbl/MMcf.

Gulf of Mexico nonassociated gas typically is relatively dry with liquid yields of about 15-17 bbl/MMcf. The world average liquid yield for nonassociated gas is about 45 bbl/MMcf.

With the low gas prices in the US relative to oil, even a liquid yield of only 10 bbl/MMcf would enhance the value of the discovery by about 10%. Our analysis assumes no liquids. Current gas prices in the US are not as robust relative to oil as in the past. For many years gas-price parity averaged about 9 Mcf/bbl. Our analysis has assumed a gas price for 2010 of $5.50/Mcf and escalated that price by 2.5%/year. With current oil prices of $75-80/bbl, the price parity is about 14 Mcf/bbl.

Except for our assumption regarding gas gravity and zero liquid yield, we made no assumption about gas quality.

Any appreciable CO2 will both reduce salable gas as well as increase costs. High temperature and high-pressure CO2 is corrosive and produced CO2 will need proper disposal. Furthermore, no information is yet available regarding SO2, since the well has not yet been tested.

Costs

MMR has reported typical costs for this deep Wilcox play at $100 million/well to drill and $50-75 million to complete. A simple 10-well development plan therefore would require nearly $2 billion in drilling costs alone.

The rig day rate for the Rowan Gorilla IV jack up rig at Blackbeard was about $195,000/day. Other services such as mud logging, cementing, wireline logging, pipe-conveyed logging, directional services, and drilling mud can nearly double daily drilling costs.

Expected rig rates for future Davy Jones drilling range from $180,000 to $220,000/day. This, combined with the naturally slow drilling at such depths, is partly why costs are so high. Furthermore high mud weights also cause relatively slow drilling penetration rates.

The earliest estimate for production start-up from the Davy Jones discovery is 2013.2 By world standards, this is relatively fast because, unlike in many parts of the world, the discovery is in the heart of a robust market and preexisting infrastructure. A large-scale gas development on the coast capable of producing 500 MMcfd to 1 bcfd, however, is beyond the capability of the current transportation infrastructure.

Fiscal terms

Compared with international standards, the fiscal terms for the Davy Jones development generally look good. Government take for Davy Jones is only about 53% (±2%). World average government take for a gas development is slightly greater than about 57%.3 But, much about Davy Jones is not average, such as high pressures, drilling costs, and risks.

Industry weighted average cost-of-capital currently is about 8.5%.4 Most companies will add a few points to this for their target rates-of-return or investment thresholds to account for difficult-to-quantify risks. Thus a typical company or investor will likely use a global discount rate of about 10-11% for a project like Davy Jones in the US.

If the project were outside the US, investors likely would use higher discount rates. This would be especially true if the project had specific risks that did not lend themselves to easy analysis and quantification.

Our analysis assumes the market response resulting in the $602 million market value was based on a discount rate of about 10-11%.

Table 2 summarizes the economic assumptions and results.

The discounted-cash-flow analysis does not take into account the value of MMR's acreage position in this play. The market response surely has factored this in, but this is difficult to tell to what degree.

It is common that several more difficult-to-quantify factors will influence the value of a production acquisition or the development project acquisition. These factors include possible reserves, undrilled prospects, acreage positions, options, and carried interests (which were ignored in our analysis).

Often these aspects can represent from 10-20% of a transaction.

From the perspective of the discounted-cash-flow value of our reserve estimate alone the market appears to have been somewhat bullish. To make such a judgment based on volumetric analysis alone on the basis of one (untested) well and only public information is also somewhat bullish. The market response, however, had to have been largely based on the generally available public information summarized here.

Value of discovery

The discounted-cash-flow value and the market value of the Davy Jones discovery are relatively consistent with what one would expect for a large discovery

Fig. 4 is based on discounted-cash-flow analysis (12.5%) of the value of a gas discovery (before development) under various price, cost, and fiscal scenarios.

The analysis used a discount rate because this graph represented both US and international assets. Assuming a gas price of about $6/Mcf, the value of the Davy Jones discovery according to this graph in the deep Wilcox should be about $0.60/Mcf.

A considerable difference exists between the value of reserves at the point of discovery and developed-producing reserves. Production acquisitions are another matter.

Producing reserves values

After appraisal and development of a discovery, the value of reserves in the ground is greater than at the point of discovery. The factors that have the greatest influence on the value of producing reserves include fiscal terms, timing (decline rate), costs, and prices. Not all reserves have the same value.

Merger and acquisition activity during Dec. 15, 2009, to Jan. 15, 2010, indicated an average reserve value of $1.69/Mcf (equivalent). This statistic represented 18 US transactions totaling $5.3 billion in acquisitions during the period (Oil & Gas Financial Journal, February 2010, p. 47). During the following month, transactions took place at about $1.88/Mcfe.

Just as with this analysis, however, it is so difficult to quantify the less tangible aspects of value that go into an acquisition that analysts are confined to taking the transaction values and dividing by the associated reserves.

Fig. 5, structured similarly to Fig. 4, shows relative discounted cash flow values of reserves under various price and fiscal scenarios. When Davy Jones is on production 10 years from now and one of the partners considers selling its working interest share of remaining reserves, one can estimate the value from this graph.

For example if gas prices are at $8.50/Mcf, the discounted cash flow value should be about $1.75/Mcf. On this figure, the Davy Jones fiscal terms fall between low and average government take for gas.

References

1. Durham, L.S., "GOM test, intrigues, Shallow Water, Deep Miocene Play," AAPG Explorer, May 2008.

2. Phillips, D., "McMoRan Exploration: Hype and Hope of Davy Jones Discovery," BNET, Jan. 31, 2010.

3. Johnston, Daniel, and Johnston, David, "International Petroleum Fiscal System Analysis and Design," Course Materials, University of Dundee, Scotland, 2010.

4. Value Line database of 7036 companies as of January 2010.

The authors

More Oil & Gas Journal Current Issue Articles

More Oil & Gas Journal Archives Issue Articles

View Oil and Gas Articles on PennEnergy.com