US ETHANE OUTLOOK —Conclusion: Midstream, petchem players must face problems of increased ethane capacity

This conclusion to a two-part series on the outlook for US ethane analyzes changes occurring in the US ethylene industry and whether that industry can consume more ethane supplies that are poised to come onto the market. This part also examines the magnitude of the ethane extraction overhang and its implications for gas producers, gas processors, and ethylene producers.

Part 1 (OGJ, Feb. 16, 2009, p. 44) described the fundamentals that drive US ethane balances, detailed the market forces driving the expansion of US gas processing capacity, and forecast how these expansions will increase the ability to extract ethane in the US

US ethane demand

The US ethylene industry consumes more than 50% of the US NGL supply. And, because ethylene production is the only end-use market for ethane in the US, it is important for any NGL midstream company to pay close attention to the health of the US ethylene industry and the actions of ethylene producers with regard to feedstock selection.

The 20-month period January 2007 to August 2008 was a fairly good one for US ethylene producers for several reasons:

- Low gas-to-crude price ratios in the US made US ethylene producers more competitive globally.

- The US ethylene industry’s ability to shift to ethane and ethane-propane mix gave it a competitive edge over heavy feedstock crackers in Europe and Asia. Those US ethylene producers leveraged to heavy feedstocks, however, suffered in the high crude price environment during first and second-quarter 2008.

- Although the US economy was slowing, the low US dollar created an export market for US petrochemicals.

- US ethylene production remained steady at around 55.1 billion lb/year (88% operating rate).

For gas processors building and announcing new cryogenic plant capacity, it appeared the ethylene industry was healthy, and those processors assumed that ethylene producers could handle additional ethane volumes coming onto the market. Yet, an assessment of the US ethylene industry over the past 18 years revealed several signs that the US industry was maturing and shifting in ways that would make it difficult for ethylene producers to crack much more ethane.

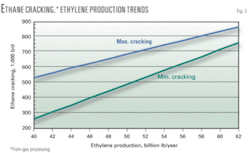

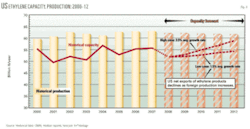

First, US ethylene capacity has stagnated and ethylene production has moved within a fairly narrowed range between 50 billion and 55 billion lb/year since 2000 (Fig. 1). This pattern contrasts to the growth period in the 1990s when ethylene capacity and production were expanding at 1.5 times that of US economic growth, based on calculations using information from Houston-based CMAI (www.cmaiglobal.com), Hodson Report ethylene production and capacity numbers (www.paceconsultants.com), and US gross domestic product growth from US Federal Reserve (www.federalreserve.gov).

US exports of ethylene derivatives were one of the major drivers for ethylene growth during the 1990s. After 2000, US demand for ethylene stalled due to slower US economic growth and reduced demand for petrochemical exports as ethylene capacity expanded overseas.

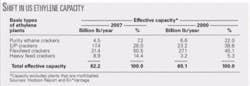

Second, spikes in natural gas prices relative to crude oil prices that occurred in winter 2000-01 and throughout most of the 2003 caused light feedstocks (ethane and propane) to be uneconomical for ethylene producers to crack and left the industry skeptical of the long-term availability of natural gas in the US. Consequently, ethylene producers shifted capacity away from cracking light feedstocks and increased their ability to crack a wide range of feedstocks and heavier feedstocks, such as naphthas and gas oils. By the end of 2007, light feedstock crackers constituted only 35% of US ethylene capacity, compared with 50% in 2000 (see accompanying table). In addition, 21% of US ethylene plant capacity is aging (35 years and older), and this capacity represents 33% of total ethane consumption.

Relatively stagnant ethylene production and the shift to more flexi and heavy feed crackers have kept the demand for ethane from gas processing well below 800,000 b/d for the past 8 years (Fig. 2). Just as important is the US ethylene industry’s current wide range of flexibility to swing off and on ethane when feedstock economics warrant. Back in winter 2000-01 and again in 2003 when gas-to-crude price ratios were well above historical averages, the ethylene industry was able to drop ethane cracking by 200,000 to 300,000 b/d in a matter of a few weeks. Conversely, in 2007 and through first-half 2008, when gas-to-crude ratios were low, the ethylene industry was able to maximize ethane and propane cracking and minimize heavy feedstocks.

The US ethylene industry’s ability quickly to swing feedstocks is largely responsible for the volatility seen in ethane consumption. Adding to this volatility, according to En∗Vantage research, is that the US ethylene industry cannot maximize or minimize ethane for a period greater than 3-4 months without disturbing the supply-demand balance for ethylene coproducts such as propylene, C4 olefins, and pyrolysis gasoline. These ethylene coproducts are valuable building blocks in producing other petrochemical products. And, because ethane cracking produces few coproducts, ethylene producers must balance their need to optimize profits when ethane is the preferred feedstock vs. keeping the coproduct market adequately supplied.

At any given production level for ethylene, ethane demand can vary, depending on whether the ethylene industry is minimizing or maximizing ethane cracking. The key to predicting ethane demand is to understand how ethane cracking can vary at a given level of ethylene production.

Over the past several years En∗Vantage has analyzed ethane cracking data vs. US ethylene production levels and has modeled the current configuration of the US ethylene industry to determine minimum and maximum levels of ethane cracking. Fig. 3 shows the results.

Two major trends appeared from our analysis:

- As ethylene production increases the need for ethane cracking increases. That is, when the ethylene industry requires that next incremental pound of ethylene, it turns to ethane because ethane is the feedstock that provides the highest ethylene yield.

- When the ethylene industry is operating at low utilization rates, it has more flexibility to swing ethane cracking levels than when it is operating at higher utilization rates. Consequently, the US gas processing industry can be subject to considerable volatility in the demand for its ethane when the ethylene industry is operating at low utilization rates, as when there is an economic recession.

The results shown on Fig. 3 make it possible to predict how ethane demand will trend for the next several years by predicting the level of ethylene that will be produced in the US in the near future. Fig. 4 shows our forecast for ethylene production; our base case is for ethylene production to average less than 55 billion lb/year through 2012 as US net exports of ethylene products decline as foreign petrochemical production increases. Absolute best or high-case scenario for US ethylene production is of 3.5%/year, taking ethylene production near 60 billion lb/year by 2012.

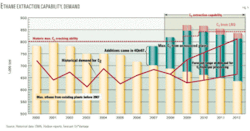

Applying our base and high case forecasts for ethylene production to our regressions for ethane demand indicates that the US gas processing industry should develop a substantial overhang in ethane extraction capability (Fig. 5). Even our most optimistic scenario for ethane demand would require the US ethylene industry as currently configured to maximize ethane cracking continuously, which would be difficult to do and still meet ethylene coproduct requirements.

Implications processors

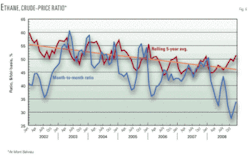

Even before the current economic downturn, the influx of more ethane on the market from new processing plants coming online in 2007 and 2008 was putting additional pressure on the value of ethane relative to crude oil, which has been in decline since 2003 due to the reduction in light-end crackers (Fig. 6).

With a long-term average near 50%, ethane’s value relative to crude started to crater in 2008 into the 30% range, reflecting the rising sensitivity of the market to additional ethane supplies. This sensitivity will only grow as more processing plant capacity comes on stream in 2009 making the ethane market more susceptible to any events that might reduce ethane cracking, such as ethylene plant turnarounds, unexpected cracker outages, or plant shutdowns due to economic reasons.

Over the long haul, devaluation of ethane relative to crude oil can be a double-edged sword for gas processors. Ethane’s lower relative value makes it a more preferred ethylene feedstock. Lower ethane-to-crude price ratios, however, expose processors to much lower ethane prices when crude prices decline and to much lower frac spreads when gas prices stabilize or increase relative to crude prices.

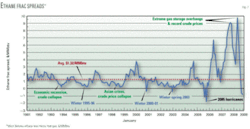

Under the current economic recession, ethane demand is off at least 25%. Consequently, ethane frac spreads have plunged into negative territory. A long-term analysis of the ethane frac spread indicates how much of an anomaly the record high frac spreads in 2007 and 2008 were in comparison of the long-term average (Fig. 7). It also demonstrates how fragile ethane frac spreads can be when economic conditions deteriorate, especially when more ethane extraction capability is brought online.

Depending on their risk profile, gas processors are being affected differently by the ethane extraction overhang. When we first identified the threat of an ethane extraction overhang about 2 years ago, we profiled which processors would be subject to the most economic risk to ethane.

Gas processors with the greatest economic risk to ethane are those processors with most if not all of the following features in their profile:

- “Keep whole” contracts.

- No ability to minimize ethane recoveries without losing propane.

- Little or no integration along the NGL value chain.

- High transportation and fractionation fees.

- High fuel usage and operating costs.

- Little or no gas basis offset.

- Low-value market for ethane.

- Little integration with a gas producer.

Conversely, those processors having most if not all the features below should have a lower risk exposure to ethane:

- Percent-of-proceeds (POP) and fixed-fee processing contracts.

- Ability cleanly to reinject ethane.

- High degree of integration along the NGL value chain.

- Low transportation and fractionating fees.

- Efficient operations.

- Wide gas basis offset.

- High-value market for ethane.

- Integration with a gas producer.

Independent gas processing companies with “keep whole” exposure to ethane and little, if any, integration along the NGL value chain are in the high-risk category and are suffering the most during the current economic recession. But even after the recession passes, independent processors with “keep whole” contracts—especially in the Midcontinent, a low-value ethane market—will continue to be at a competitive disadvantage to the larger integrated midstream players with processing.

Integrated players can operate under variable cost economics for the transportation, fractionation, and storage of their NGLs, which gives them an economic advantage to keep recovering ethane when many independent processors may not have the economics to recover.

Also, those processors with POP contracts have greater staying power to continue to recover ethane when ethane frac spreads are negative. Over the past several years many processors retooled their processing contracts from “keep whole” to POP. During an economic recession when ethane demand is down, more ethane supplies can still come onto the market. Gas processors with POP contracts usually have the economics to recover ethane, further aggravating the oversupply situation for ethane and keeping ethane frac spreads at very marginal levels.

There is always the possibility that reduced drilling due to depressed natural gas and crude oil prices will curtail gas production growth and NGL extraction. This is difficult to quantify, and, besides, the effect on gas production, if it occurs, may be short lived because reserves are present.

Unless the economic recession causes processors to cancel or delay processing plants that are announced to come online, ethane extraction capability is on track to exceed the ability of the ethylene industry to crack ethane.

The ultimate key to “lifting all boats” in the processing industry will depend on efforts by US ethylene producers to increase their capability to crack more ethane at existing plants, because additional ethylene capacity will not be built in the US in the foreseeable future. Obviously the economy needs to improve, but before the economic recession hit, many ethylene producers that were leveraged to heavy liquid feedstocks were examining ways to access and crack more ethane at their facilities.

En∗Vantage estimates that the US ethylene industry could increase ethane cracking capability by another 50,000 to 75,000 b/d at existing plants, but several obstacles remain:

- Some heavy-feed crackers are isolated from large ethane distribution systems. Additional ethane distribution pipelines are needed to access these ethylene plants. Midstream companies are reluctant, however, to bear the full risk in building more logistics to handle ethane without the ethylene producer guaranteeing a minimum throughput.

A key point to remember is that ethylene producers will always have the option to crack more or less ethane, depending on feedstock economics at any given time. Gas processors and NGL midstream players, on the other hand, are making the commitment to extract and distribute the ethane.

- Maximizing ethane cracking at some heavy-feed ethylene plants may require investments to retool the plants’ process equipment to handle a product stream richer in ethylene and lighter hydrocarbons. There is the problem that if more ethane is cracked, coproduct production could suffer, and petrochemical companies will need to find ways to meet downstream coproduct requirements.

Additionally, the economic slowdown plus more ethylene plants worldwide could dampen a petrochemical company’s enthusiasm to make investments to access and handle more ethane.

- Most importantly, ethylene producers need to be convinced that ethane supplies will be reliable over the long-term. Historically, the nation’s petrochemical industry has always been skeptical of the long-term viability and competitive pricing of natural gas resources and hence NGLs in the US.

It will take a continuous effort by gas producers, processors, and NGL midstream players to assure the petrochemical industry that natural gas reserves, production, and NGLs are sustainable over the long haul.

Undoubtedly, the severity of the current economic recession is distorting the supply and demand for ethane, but when the recession is over, the prospects for an ethane extraction overhang remain. Gas processors that have made investments in extracting ethane could continue to see marginal returns.

It will require the ethylene industry to make a concerted effort to increase its ethane cracking capability. If the ethylene industry responds, there are unique opportunities for integrated midstream players to expand and grow, which could ultimately help independent processors. More NGLs require more NGL take-away capacity, greater need for full fractionation, particularly in Mont Belvieu, and additional distribution pipelines to deliver ethane to ethylene plants that lack sufficient access to ethane.

Observations

The US gas processing industry has always been focused on serving the natural gas producer either extracting as much value out of the natural gas stream or conditioning the gas. Gas processors have always assumed that NGL markets would be sufficient, and it would have been unusual for a cryogenic processing plant to be built for the sole purpose of serving the petrochemical market for ethane.

The current economic recession has painfully reminded gas producers and gas processors that the economic viability of any processing plant that maximizes ethane recovery is intricately tied to the health and actions of the US petrochemical industry.

The problem is that the US petrochemical industry is unlikely to expand ethylene capacity in the foreseeable future and the recent recession has actually caused the industry to contract. More gas processing capacity coming online will prolong the ethane extraction overhang, and all participants involved in gas processing and the handling of NGLs will need to prepare for a greater frequency of marginal ethane extraction economics and lower recoveries even when the economy improves.

Gas producers and processors need to take an active role in promoting the long-term availability of natural gas and ethane in the US because greater cooperation and sharing of economic risks between midstream and petrochemical companies are required to increase the capability to crack more ethane at existing ethylene facilities.

For petrochemical companies, this is a unique opportunity to increase feedstock choice by taking advantage of ethane’s growing availability and lower valuation relative to competing feedstocks.

In the meantime, individual processors looking to build that next cryogenic processing plant must carefully assess their competitive positions against more integrated midstream players, the market’s need for more ethane, and the relative value for the incremental ethane barrel. No longer can the ethane market be taken for granted by the gas processing industry.

- Some heavy-feed crackers are isolated from large ethane distribution systems. Additional ethane distribution pipelines are needed to access these ethylene plants. Midstream companies are reluctant, however, to bear the full risk in building more logistics to handle ethane without the ethylene producer guaranteeing a minimum throughput.