One of the priorities for the European Union (EU), which now comprises 27 member states, is advancing its gas and electric power liberalization agenda. Adoption of its third energy liberalization package would move the EU closer to that goal, but adoption still faces a number of obstacles.

Protectionism of national monopolies has been at the core of a 10-year battle against opening markets to new participants. However, security of supply is now one of the EU’s major energy objectives, and the longer market liberalization is delayed, with companies not investing in a timely manner, the deeper is the risk of endangering supply security.

In 2003, the International Energy Agency projected that during 2001-30, the estimated cumulative gas investments [within the EU-15 countries] would amount to $85-95 billion for distribution, $50-75 billion for transmission, $10-15 billion for storage, and $15-20 billion for LNG regasification.

The EU’s other energy policy objectives—competitiveness and sustainability—also complicate the execution of liberalization: They are not always compatible. Choices must be made considering short-term/long-term contract inconsistencies, failures in the market, and public intervention, according to a report by European think tank Bruegel.1

Now in an economic downturn, with a tightening of credit markets, operators are even more hesitant to make investment decisions because of regulatory uncertainty. In the early part of this year, negotiations urgently need to be concluded among the European Commission, European Council, and European Parliament over the third energy package, which contains a number of controversial measures, including the suggested mandatory ownership unbundling of vertically integrated energy companies.

European elections for its parliament are scheduled for June, and a new commission is be convened in 2010. New faces and new attitudes could mean the unraveling of all the work on the package to date, prompting a fourth energy package and more passionate debate.

Once a compromise is reached on the sticking points, the revised package will go to the parliament for the second reading on Apr. 21-24, either approving a compromise reached with the council or reintroducing its first-reading amendments, a parliament spokesman told OGJ. Other areas under discussion include conditions for third-party access to natural gas transmission networks and the rules for the internal market on natural gas.

“We are confident that we can reach a compromise on the third energy package,” an EC spokesman told OGJ. “All parties have a big interest to reach a compromise; no one wants to be accused of delaying the package.”

If the legislation passes this hurdle, the gas industry will focus on submitting comments on how the new regime will be implemented.

But Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) are not as optimistic about brokering an agreement by April. Some have accused the EU’s Czech presidency of failing to take the negotiations seriously, despite its being a colegislator with a majority on the energy package.

OAO Gazprom, which provides a quarter of the EU’s gas supplies, is also carefully monitoring the trilogue so it can decide how to proceed with its new export pipelines. A spokesman told OGJ: “We hope that the deliberations between the council and the parliament will lead to an outcome that will encourage cross-border investments from all parties, including those companies from outside the EU that are willing to pursue business opportunities in the EU member states and bring added value to Europe’s energy infrastructure.”

This special report focuses on some of the more contentious provisions of the commission’s draft legislation: ownership unbundling, the Gazprom clause, and the creation of a new European energy regulator.

EC’s third package

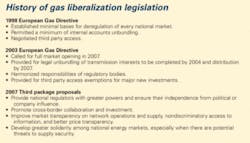

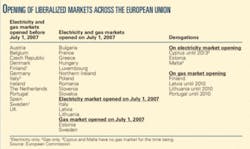

The third energy package was published in September 2007. These measures aim to bring effective competition to the European market, as previous legislation—the EU Gas Directive of 1998 and the Second Energy Directive of 2003, have not been entirely successful (see box below).

Full unbundling

The EC proposed full ownership unbundling—separation of supply and transport-transmission—so that all companies can have access to the networks. Energy companies would be required to sell their assets because legal unbundling, where companies create separate transportation and supply legal entities under a common parent company or ownership structure, had not been successful.

In its 2006 competition enquiry and in other studies, the EC had found that vertically integrated former monopolies blocked other companies from accessing networks and pipelines. However, investors could retain their interest in the dismantled groups via a share-splitting scheme under this measure, the commission said.

Member states such as France and Germany, which have national champions, believe ownership unbundling is unconstitutional. They contend that selling these assets could endanger energy security and leave consumers with higher prices. Opposing states also feel that it adds another level of bureaucracy, considering that legal unbundling was recently introduced.

Germany’s support for the commission’s package is critical. With the second largest gas market in Europe, Germany would determine how its neighbors trade.

“Likewise, Germany is geographically located at the heart of the European gas market, where gas from all key sources of European gas (the Netherlands, Norway, Russia, and, to a lesser extent, Algeria) meets,” said consultancy IHS Global Insight.

Vertically integrated companies tend to view networks as strategic assets for their own commercial interests, rather than for serving the overall interest of network customers. “In particular [such companies] underinvest in new networks, fearing that these investments might help competitors to prosper on its national market,” said the Committee of Regions (COR), which represents the subnational regions of the EU.

What would be the impact of this policy on Europe’s biggest gas exporter? Gazprom has made no secret of expanding its position in Europe through buying stakes in transmission and distribution systems, or developing partnerships with them.

Catherine Locatelli, a researcher at the French think tank LEPPI, warns that the growth of Russian gas production will not be independent of the institutional modifications of the EU, Gazprom’s principal export market. The commission’s full unbundling policy could push Russia to seek diversification of its exports on a grander scale.

Independent operator

The commission’s second unbundling model for energy companies would be to establish an Independent System Operator (ISO) that would assume operational control of the networks. Companies with energy production and supply assets could keep their networks, but an ISO would be appointed by national governments to decide on the use of the infrastructure and on investment plans. This would stop the transfer of privileged information, discrimination, and bias. This alternative was suggested to stave off hostility about full unbundling, but it wasn’t well received by member states, who felt it would infringe upon their property rights.

The disadvantage of this concept is the increased regulatory burden, the commission warned, because it would have to be confident that the designation of the ISO was independent. Furthermore, network owners must work with the national energy regulator to implement its 10-year network investment plan and comply with the ISO’s financial investments in transmission capacity.

Another issue is having confidence that the ISO would not be swayed by the major supplier and incumbent transporter, which would be its largest buyer and the provider of all its capabilities. In addition, utility shareholders would suffer a loss of control and privatization of these assets.

Market approaches

According to the commission’s suggestions, the same approach on ownership unbundling should be used in both the gas and electricity market. But critics have pointed out that the EU is a major importer of gas from non-EU countries and so the focus should be on security of supply, given its vulnerability to the geopolitical crises of its gas providers.

Clearly the dispute between Russia and Ukraine and its impact on Europe earlier this year was a pertinent example of this point. Russia stopped gas supplies to Ukraine for its own domestic use because it claimed Ukraine failed to pay its debts on time (OGJ Online, Jan. 2, 2009). In turn, Ukraine, which is a transit country to Europe, stopped sending gas.

In its working document published on Jan. 9, 2008, the parliament said that because there were also structural differences between the two markets, “it may be necessary to consider the possibility of opening up the gas market more slowly than the market in electricity.”

Council’s response

The EU Energy Council, however, took a different approach to ownership unbundling and published its response to the document last October. This model, although similar in objective to the ISO, differs in its internal organization and introduces more bureaucracy to stop vertically integrated energy companies from being unfair and discriminatory in running their transmission and distribution networks to other entrants. After intense lobbying by member states—led by France and Germany—it said companies could keep their transmission businesses, provided they were monitored by an Independent Transmission Operator (ITO). Effectively the transmission system would be legally unbundled from energy production.

However, to assuage the fears of nations such as Spain that their unbundled companies would be bought by rivals who had more financial clout, these energy producers would be prevented from purchasing the grid businesses of energy companies in European countries where full unbundling had occurred.

In effect, all three models of unbundling could exist side by side across the EU, but it’s hard to accept that this would result in a level playing field between transmission system operators and member states.

Parliament’s views

During its first reading of the commission’s proposals, the EU parliament rejected the ISO model as the alternative to full unbundling in gas. It is prepared to accept the council’s position on the gas industry but is pushing for full unbundling in the electricity market. The key question now during the talks among the commission, council, and parliament is whether they can agree to a compromise on the model for unbundling so the package can secure the 51% vote needed during its second reading in parliament and be adopted in member states.

With the ITO model, parliament has introduced additional measures, such as a supervisory body and compliance program, to ensure that utilities comply.

It also has called for a new regulatory agency to report on the progress of the system within 5 years, and if it finds that this has failed, it possibly could demand complete unbundling.

The parliament also is keen to ensure that consumer protection is a core aspect of the directive, arguing that, with the current lack of transparency in the gas market, customers “do not currently receive full information about the product consumed; energy bills are often indecipherable,” it said.

“Consumers must be able to make free, timely, and informed choices in a transparent and competitive market…not subject to external (explicit or implicit) price regulation mechanisms, which undermine price-forming mechanisms and, consequently, the operation of competition.”2

The ‘Gazprom clause’

In the commission’s third package it offered a “third country” clause (also known as the “Gazprom clause”) wherein reciprocity was key for non-EU companies wanting to snap up distribution and transmission networks in EU member states. They could only do so provided that they granted similar rights to EU companies in their home countries, and the commission and the respective country would sign an agreement to that effect. Furthermore, non-EU companies would have to “demonstrably and unequivocally comply with the same unbundling requirements as EU companies,” the commission said.

Unsurprisingly, with Gazprom keen to expand its position in Europe, Russia has not welcomed the commission’s move. Gazprom is in dialogue with the EU to ensure reliability of long-term supplies under this clause. Moving downstream gives Gazprom better access to customers and is quite profitable because liberalization alters the distribution of income in the gas chain.

Roman Zyuzev, an academic at Institut Europeen des Hautes Etudes Internationales, describes the clause as “unclear and vague” and says it requires discussions to help flesh out the EU’s and Russia’s new partnership and cooperation agreement.

The parliament endorsed the commission’s clause to protect the EU’s energy security. Europe has tried to pave the way for its companies in Russia in the past but has been unsuccessful.

But the council, after strong lobbying by member states who were worried about upsetting Russia—because they import large quantities of its gas—said it wanted a more diluted version of the clause. It has proposed that an EU member state could strike an individual bilateral agreement with a foreign country before its companies could buy the energy pipelines and grids of that EU nation.

EU regulator powers

Under the commission’s draft legislation, a new European regulatory agency would be set up to focus solely on the regulatory gap for cross-border transactions in gas and electricity. It found that full development of the market has been impeded by a lack of coherence in the powers of national energy regulators.

The Agency for Coordination Energy Regulators (ACER) will be empowered to review, “on a case-by-case basis,” decisions made by national regulators and to facilitate cooperation between network operators.

However, ACER’s powers will be strictly limited to cross-border issues. “The agency is not a substitute for national regulators, nor is it a European regulator,” the commission said.

Fears about this measure centered on introducing new levels of bureaucracy and on shifting powers from national regulators to Europe.

New approaches

Regardless, the council supported this idea and decided that within ACER’s voting system, all countries will have the same voting weight despite Germany’s campaign to give larger countries with bigger energy networks more clout over the agency’s decisions.

But parliament’s stance, compared with the council’s, is tougher on ACER’s powers. It is seeking to hold ACER more accountable: Its director should be subject to a vote of approval by parliament and should regularly update that body on the performance of his or her duties.

In its comments, the COR rejected establishing a European energy regulator because it says national regulators can achieve the commission’s objectives. It also has called for the European Regulators’ Group for Electricity and Gas to be strengthened, particularly for cross-border problems.

References

- Roller, L.H., “Energy: Choices for Europe.” Roller is the former chief economist at the Directorate General for Competition.

- Committee on Industry, Research and Energy, Jan. 9, 2008. Working document on the proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the council amending Directive 2003/55/EC concerning rules for the internal market in natural gas.

Exporters’ views…

Europe’s three largest gas exporters are Norway, Russia, and Algeria. The process of liberalization affects them with price and volume risks.

Gas liberalization also has implications for their relationships with the EU on security, diplomacy, and foreign policy. Liberalization results across the EU have been patchy, and countries wish to deal with a single integrated market, rather than 27 different regulatory systems as multiple systems add complexity and increase costs.

Russia’s Gazprom provides 25% of the EU’s gas supplies, and it feels fundamentally that long-term import contracts are crucial, considering the scale of the investments required for gas projects.

One opportunity arising from liberalization would be driving its spot trading to another level, although supplying gas solely on this basis would be too risky. In 2007, the company’s trading arm sold 6.7 billion cu m of gas on the trading floors of the UK, Belgium, Netherlands, and France. This amount exceeded the level of 2006 by 25%.

Although it recognizes the complexity and level of investment for the gas business, the commission is troubled by the nature of long-term contracts, which in effect, distort the concept of competition.

For Algeria, Energy Minister Chakib Khelil has said that long-term contracts put it at a disadvantage because revising its prices depends on the goodwill of its European customers, and this is sometimes difficult to secure. It is pushing for short-term contracts because prices would be more favorable. Khelil has been critical of the mixed results of gas liberalization across the EU because each member state continues to act in its own interests rather than adopting a common policy. A major risk with liberalization is that it endangers supply guarantees because exporters will focus on those customers who can pay the best price.