Special Report: IOC challenge: providing value beyond production

In their effort to access hydrocarbons, international oil companies (IOCs) face a major challenge: convincing national oil companies (NOCs) and host governments that they provide value beyond finding and producing oil and gas.

In the 1970s, international oil companies held approximately 85% of the world’s known hydrocarbon reserves. These integrated majors dominated the upstream business as they crisscrossed the globe making deals and developing oil and gas around the world. Yet just 3 decades later, the IOCs’ share of reserves has plummeted to less than 10%, with industry estimates ranging from 6% to 8%.

Today, NOCs—once relegated to second-tier status behind their larger, richer, more accomplished global peers, the IOCs—control as much as 94% of the world’s oil and gas reserves. As few as 10 nations—led by Saudi Arabia at 22%—account for half of total oil production; just three countries control more than half of the world’s natural gas reserves.

The concentration of hydrocarbon access in the hands of an ever-smaller number of NOCs has been accompanied by a corresponding shift in the energy industry’s power structure. Today, some NOCs rival the size and scope of the largest independent majors; many wield tremendous influence over current and potential partners. Some, in fact, are competing directly against IOCs for access to reserves in foreign markets.

At the same time, other market players in the global energy industry have stepped up to take on roles previously dominated by IOCs. Major oil field services firms now have the global reach and capability to provide in-depth technical and project execution skills. Private equity firms and sovereign wealth funds offer the significant capital necessary for today’s large-scale production efforts. And third-party marketers provide distribution access.

Venezuela’s reversal

One well-documented recent example shines a penetrating light on the new-found boldness of some NOCs. In the early 1990s—with crude oil prices below $20/bbl—Venezuela’s national oil company, Petroleos de Venezuela SA (PDVSA), was losing money on the low-quality, extra-heavy crude found in vast amounts in the country’s Orinoco basin. Production was expensive and time-consuming, and few refineries could process the oil once it was above ground.

With insufficient capital to invest in production equipment that could turn Orinoco heavy crude into a lighter grade suitable for most overseas refineries, the Venezuelan government reversed a 1976 decision to nationalize its oil assets and invited a number of IOCs to return to Venezuela and invest in the Orinoco basin.

To lure the IOCs, Venezuela offered low tax rates and a royalty of just 1%. The IOCs returned, investing billions of dollars in equipment, infrastructure, and technology in the process.

But less than a decade later, responding to much higher commodity prices, the Venezuelan government reversed its position, dissolved its operating service agreements with the IOCs, and forced foreign companies into joint ventures, giving the government ownership stakes that approached 80%. Faced with accepting the new terms or abandoning their investments, most investors took what was offered.

The Venezuelan government’s approach underscores the dramatic change in relations between IOCs and their NOC counterparts. As commodity prices rose through mid-2008, along with the earnings of global majors, host governments became increasingly wary of existing production-sharing agreements and other contractual arrangements.

While Venezuela’s unilateral action is frowned upon both publicly and privately by IOCs, other host nations are working in less dramatic but equally productive ways to gain benefits from majors eager to do business—often asking for deeper relationships that go beyond simple resource development to include technology transfers, skills training, infrastructure support, economic development, and more.

It is in this more competitive, more demanding environment that IOCs find themselves seeking ways to maintain long-term relationships with NOCs and host governments that are productive, profitable, and equitable to all parties.

The value proposition

IOCs remain critical to helping resource-rich nations unlock the full potential of their oil and gas reserves. The ever-growing scale and complexity of future oil and gas development projects guarantee that IOCs will continue to play a vital role in meeting the world’s energy needs.

The ongoing growth in energy demand has some industry experts predicting that worldwide capital spending on new projects could reach $400 billion during 2008-15. Much of that spending is slated for so-called “megaprojects,” with individual costs greater than $5 billion each.

These types of complex, high-dollar, high-risk projects will continue to provide opportunities for IOCs that can effectively integrate their offerings and provide a single-resource partner for NOCs, one that can leverage existing capabilities to create value beyond production.

Indeed, while NOCs have built technical expertise and improved access to capital in recent years, they still rely on IOC partners, which bring a full complement of skills, knowledge, and technology to their partnerships, especially for large-scale, high-cost, complex projects.

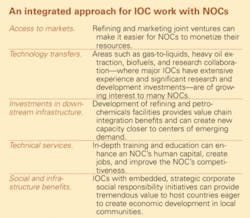

The key differentiator for IOCs today is their ability to integrate these multifaceted offerings to meet the unique needs of NOCs. IOCs that adopt a “custom package” approach of value-added skills and technology will find themselves with advantages not shared by vertical-market competitors such as individual financiers, oil field service firms, project management companies, and product marketing firms.

For example, the world’s major IOCs have unparalleled expertise in maximizing the value of reserves over the full life cycle of the field. From project planning and execution to operations management and the ability to deploy new technologies that extend production long past original projections, this type of integrated approach—melding technology, skill, and hands-on experience—ultimately results in more energy and much higher financial returns for host nations.

Contrasted with the higher complexity of working with a number of individual vertical market firms—along with the possibility that total production from a project may not be as high as expected due to the lack of integrated technology and expertise—the IOC value proposition becomes clear.

An example of an integrated approach could be a partnership of an IOC and an NOC to develop natural gas resources in which the companies don’t stop at a production-sharing agreement but instead also agree to jointly develop LNG processing and delivery facilities and infrastructure, petrochemical manufacturing, and a high-tech training center to develop local skills.

New mindset

It is clear that IOCs must have a change in mindset toward their relationships with NOCs. The traditional relationship between IOC and NOC was, in many ways, a simple partnership of convenience. The NOC needed help in developing reserves; the IOC wanted access.

Today, however, there is a wide range of economic, political, and social implications inherent in every IOC-NOC discussion. Host governments are no longer satisfied with purely commercial agreements, even those with very favorable terms. They view the natural resources of their countries as a tool for financing social reform, boosting economic development, improving infrastructure, and creating jobs, along with a host of other individualized needs.

Thus, the IOC that sharpens its ability to listen carefully and respond to each government’s unique vision for its resources and country as a whole will be the one that gains a global reputation as a “partner of choice.” Understanding local customs and history and recognizing the host nation’s desire for its future can be invaluable in crafting contractual agreements that meet the country’s expectations for its partnerships.

At the same time, IOCs that prove their ability to develop local work forces—through education and training; the support and use of local vendors and contractors; and infrastructure development that underpins employment, such as building schools and roads—will no doubt receive strong attention from NOCs seeking long-term partners.

The work force

IOCs also must not let their own work-force development efforts lag. In order to maintain their competitive advantage over “single-role” players, it is imperative that IOCs strengthen their scientific, engineering, and project management skills by hiring and training a new generation of employees. The looming talent gap in the energy industry has been well documented, and it is here that IOCs are most vulnerable to competition.

The ability to plan and execute large-scale, complex development projects has long been a key differentiator for IOCs, yet the world of top-quality project managers with this level of skill is small, and there is plenty of demand for the services of these professionals. At the same time, many of these highly skilled employees are in their 50s or beyond with retirement looming. The IOCs that invest in developing the “next-gen” talent pool will be leaders in future partnership efforts.

The importance of human capital cannot be overstated for energy firms seeking a competitive advantage in the coming years. Recruiting, training, and retaining skilled technical employees should be a major area of focus for every energy organization, and it should receive the full attention of senior management. Outside expertise in planning and implementing enterprise-wide human capital programs—integrating all facets of human resources, including compensation, skill development and training, and succession planning—can be a valuable asset to major energy companies seeking to implement long-term cultural changes that will attract and retain employees.

Workers that are well versed in subjects such as local tax laws, deal structuring, financial requirements, customs, and the political and business climate can be extremely valuable to energy companies doing business around the globe. These types of advisory skills complement companies’ in-house knowledge and strengthen their ability to construct agreements that benefit all parties.

Listening and responding

To be successful in today’s environment, IOCs must demonstrate and communicate that they seek long-term partnerships with NOCs and possess an organizational culture that is focused on listening and responding to the full range of host governments’ social and economic needs.

IOCs must realize that investing in and developing local work forces and supporting economies are necessary parts of doing business around the world and that their ability to do so is another competitive advantage over smaller, single-service competitors.

In addition, IOCs must learn to package the elements of their core value proposition—technology, financial resources, access to markets, project execution expertise, and vertically integrated offerings—in innovative ways that are customized to each market. Adaptability is the watchword for future contractual negotiations; the willingness to seek out balanced, “win-win” agreements is key.

Meanwhile, IOCs must recognize and respond to the looming talent shortage in the energy industry by designing enterprise-wide human capital programs that strengthen their ability to attract, train, and retain key employees who bring the skills and expertise that NOCs need. And they must continue to work to develop their in-country relationships with experts in tax, financing, and other local financial and business regulatory issues in order to negotiate from positions of knowledge and understanding.

The global power shift is real, and it has serious implications for the future business prospects of IOCs. But those that are willing to adapt to the shift—and who do so quickly and successfully—will maintain their competitiveness and viability in the decades to come.

The author

Rob Jessen is an oil and gas leader at Ernst & Young’s Houston-based Americas Oil & Gas Center. He has been with Ernst & Young, Capgemini Ernst & Young, and predecessor firms for 27 years, 18 years as a partner and vice-president. Jessen, whose primary expertise is downstream operations, has consulted more than 60 energy companies in well over 700 consulting projects. He is a graduate of the University of California at Berkeley and has appeared as an expert witness before the US Federal Energy Regulatory Commission in Washington, DC, and in various state jurisdictions.