Oil, gas supply trends point to tight spots, higher prices

At the beginning of the millennium oil prices were $27/bbl and essentially remained at this level through 2003. But soon afterwards they began a steep climb, reaching $99 in November 2007 and a record high of $145 in July 2008.

This finally created awareness among analysts that the world was struggling to sustain oil production and that it may not be possible to increase supply beyond a certain level. Indeed, crude oil output remained flat at around 71 million b/d from 2004 through 2008, and during this period the growing demand for petroleum liquids was satisfied mainly with additional natural gas liquids.

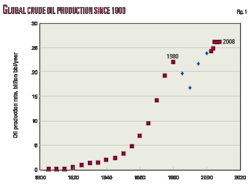

Global crude oil production has increased continuously from the 1900s until 1980, when demand dropped significantly during the last major world recession. Production hit a low of 53 million b/d in 1985, a huge 10 million b/d plunge from a high of 63 million b/d in 1979. It took 25 years for demand to return to its previous trend (Fig. 1, purple/square dots).

Astoundingly, over the last 30 years world crude oil production has increased just 8 million b/d in spite of the growth of offshore production—from 9 million b/d in 1980 to 25 million b/d in 2008—and the existence of a shut-in spare capacity of 10 million b/d from the 1980 recession—a total of 26 million b/d of available output. Onshore production in the mean time has remained flat, around 46 million b/d over the last 2 decades (Fig. 2).

This disproportionately diminished net production increase of 8 million b/d over a 30-year period results from the perverse synergy that occurs between reserves depletion and production decline.

Global exploration and production trends for crude oil over the last 8 decades are disturbing (Table 1). Discoveries of new reserves grew from an average of 19 billion bbl/year in the 1930s to a peak of 55 billion bbl/year in the 1960s. Thereafter they have declined continuously, reaching 15 billion bbl/year in the 1990s and 10 billion bbl/year in this millennium.

New reserves markedly exceeded oil production (depletion of reserves) up through the 1970s. At the zenith of exploration successes in the 1960s they were five times production, but from the 1980s to the present, the reserves/production relationship has become inverted—today's production rate is three times that of discoveries, 26 versus 10 billion bbl/year.

Reserves are the foundation of production potential. If the reserves base is being depleted, production capacity inevitably declines, and this clearly has been the situation since the 1980s.

These shortcomings of discoveries are not due to a lack of spending as some have suggested. Global E&P capex has increased fourfold in this millennium, to over $450 billion in 2008.

Crude oil supply

The logistic model has proved to aptly handle the upstream fundamentals of reserves growth/depletion and production growth/decline of oil and gas fields and their clusters as in the case of country analyses.

Fig. 3 shows the global outlook for crude oil production capacity through the end of the century using this model. Superimposed on the graph are the demand projections of the US Energy Information Administration through 2030. Supply and demand projections begin to decouple early on.

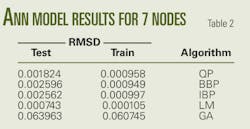

Table 2, based on EIA's forecasts, gives a breakdown of the different supply sources that make up the total petroleum liquids output. Crude oil is the most important source and accounts for 83% of the total.

The crude oil production potential of the reserves as estimated by the logistic model is also shown in the table. The crude oil outlooks of the IEA outpace production capacity in 2015 and 2030, with shortfalls of 1.7 million b/d and 12.7 million b/d, respectively.

More outstandingly, however, the IEA's outlook shows continued growth in crude oil production while the logistic model indicates decline. It is also worth noting the importance of NGLs in the supply mix. NGL production would have to double by 2030, to 20 million b/d.

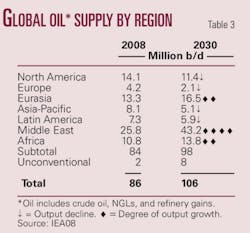

The IEA also provides a breakdown of expected oil outputs for the world's seven oil producing regions (Table 3). Production in four of the regions (North America, Europe, Asia-Pacific, and Latin America) is on the decline, leaving three regions (Middle East, Eurasia, and Africa) to provide the necessary volumes to meet demand by 2030.

With the Middle East region having the highest expectations, it would have to increase its current output by 67%. Africa and Eurasia would have to increase their present production by 27% and 25%, respectively. These assumptions of output growth are conditioned to timeliness and commitments to large capital investments, exploration successes and geopolitics.

Development costs are huge and spiraling.

In Kashagan, the largest oil field discovered in the last 20 years, these costs have recently jumped 22% to $38 billion, and the field is not set to go on stream until 2012.

Regarding exploration efforts, not only are we now discovering less reserves but the size of the new fields is much smaller. Over the last 10 years, the average new field size is 28 million bbl worldwide, and for the Middle East it is a paltry 54 million bbl. All of these factors point towards the complexities that lie ahead to meet a continual growing demand.

There is evidence that we are emerging from the current world recession. In 2010, GDP is expected to climb to 2.7% from a negative growth rate of 1.2% this year. As the global economy picks up, however, supply/demand will inevitably revert to the imbalances of the mid-2000s that brought on $145 oil. And that implies possibly three-digit oil prices lurking on the horizon.

Natural gas supply

Natural gas is considered the queen of the fossil fuels mainly because it is the cleanest of them all.

In a world that is in transit to a low-carbon economy this has led to an abnormally high increase in gas production as energy demand worldwide shifts towards this resource for electricity generation and natural gas vehicles. Gas demand in countries outside the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development group is now larger and growing faster than in the OECD countries.

Supply/demand has increased a sizzling 30% in the last 10 years, from just over 220 bcfd to 287 bcfd presently and, according to the latest demand models, is expected to further increase 50% to reach 337 bcfd by 2015 and 425 bcfd by 2030. The Big Three producers—Russia (63 bcfd), the US (51 bcfd), and Western Europe (28 bcfd)—are also the biggest consumers and together account for 50% of output and consumption worldwide.

Exploration trends indicate that we have discovered abundant reserves of natural gas, particularly since the 1960s (Table 4). In fact, globally there is as much conventional natural gas reserves as there is oil—an estimated ultimate recovery of 14 quadrillion cu ft, or 2.4 trillion bbl of oil equivalent. The natural gas industry is relatively young and vigorous. Only 22% of the gas discovered has been produced in comparison with 46% for oil. Presently, production and discoveries are in balance at around 100 tcf/year.

The logistic model indicates that global natural gas production capacity would exceed demand over the next 25 years (Fig. 4). However, there are some tight spots of natural gas supply over the medium term.

The latest assessment of the IEA provides a breakdown of future natural gas outputs for the world's seven gas producing regions (Table 5). Production from North America and Western Europe, two of the largest consumers, will be on the decline, and the key to meeting a world demand of 425 bcfd by 2030 lies in the Middle East. Qatar and Iran would have to triple their current production level; Eurasia (largely Russia and Turkmenistan) would have to increase its current output by 30%; Asia-Pacific by 67%; while Africa and Latin America would have to double their current outputs.

These assumptions of output growth are also strongly subject to uncertainties in investment levels and geopolitics. By 2030 the Middle East and Eurasia together would control 50% of the world's natural gas output compared with 40% today. In fact, they would have to provide 50% of the increase (53 bcfd) in production required to meet global demand as early as 2015, that is in the next 5 years.

Contrary to the case of oil wherein reserves are dwindling, gas reserves are not an issue. Five regions have sufficient gas reserves to cope with the future production capacities called for but would require massive capital investments for their development.

The world's largest gas field, North field-South Pars, shared by Qatar and Iran, presently produces less than 10% of its potential of 110 bcfd. Turkmenistan's Iolotan, the world's second largest, has a potential of 30 bcfd but is undeveloped and has special problems—high carbon dioxide content and high reservoir pressure.

The potentially massive gas reserves in the Yamal Peninsula of Russia are undeveloped. Shtokman, the world's sixth largest gas field, was discovered in 1989 and has a capacity of 11 bcfd but is yet to go on line. Yamal's development cost is currently estimated at $100 billion. Clearly, Russia/Eurasia needs investors with big pockets and the best technology.

Gas prices have historically lagged those of oil. Over the last 20 years gas prices have varied, on a thermal equivalent average annual basis, from 10% to 50% below those of oil. In the new global energy setting with impending supply/demand imbalances, it is almost safe to say that in the not too distant future gas prices will inevitably move towards more symmetry with those of oil.

Closing remarks

Global crude oil production has increased just 8 million b/d in the last 30 years and has remained flat at 71 million b/d since 2004.

There is evidence that we are emerging from the current world recession. As the global economy picks up, however, supply/demand of crude oil will inevitably revert to the imbalances of the mid-2000s that brought on $145 oil prices. And that implies possibly three-digit oil prices lurking on the horizon.

Although worldwide gas production capacity would exceed demand over the next 25 years, there are tight spots of supply over the medium term, not for a lack of reserves as in the case of oil but for a need of massive investments to develop existing reserves. The Middle East and Eurasia would have to provide 50% of the increases in production (53 bcfd) required to meet global demand as early as 2015.

Because of impending supply/demand imbalances, in the not too distant future gas prices will inevitably move towards more symmetry with those of oil. At present they are about one-half the price of oil.

The author

Madagascar

Spectrum ASA, Oslo, will reprocess 6,000 line-km of seismic data off Madagascar under an agreement with state-owned OMNIS.

The surveys include data offshore the west, south, and east coasts and are located in the Morondava and Majunga basins, the Cap Ste.-Marie, and Ile Sainte-Marie areas, respectively.

Spectrum will produce new datasets for open blocks off the south and east coasts, and the west coast where a long line ties both awarded and open blocks.

Previous interpretation of the data suggests encouraging prospectivity for hydrocarbons, Spectrum said.

Pennsylvania

St. Mary Land & Exploration Co., Denver, is laying a temporary pipeline to test its first Marcellus shale gas well in Pennsylvania, where it holds 41,000 net acres in McKean and Potter counties.

The company has 70% working interest in the Potato Creek-1H and 3H horizontal wells in McKean County.

More Oil & Gas Journal Current Issue Articles

More Oil & Gas Journal Archives Issue Articles

View Oil and Gas Articles on PennEnergy.com