Iraq’s E&D Future —2 Impediments abound to exploiting Iraq’s vast petroleum resource

The traditional go-slow approach of the Iraq Petroleum Co. and its associated companies, its ability to shift exploration and production to where it best served its interests and to strengthen its negotiating power; as well as Iraq’s politically-driven, confrontational oil policy, unnecessary and destructive wars, and years of sanctions, have proven to be serious impediments to the development of Iraq’s oil industry.

Today, there are further serious obstacles that limit the Iraqi government’s ability to govern effectively and to promote cooperative and coordinated policies by the different components within any ministry or between ministries. These involve failed state impediments, ethnosectarian divisions, widespread corruption, and the near absence of functioning institutions and proficient human resources.

This is demonstrated, for example, in the Kurdistan Regional Government’s unilateral decision to manage oil and gas resources within the region and so called “contested territories” without reference to the Iraqi national government, parliament, or the central Ministry of Oil, forcing the ministry to pursue its own development policy.

Both are disadvantaged by the absence of a national petroleum law and the benefits of approved regulated oil policy and plans. There is a risk, indeed for both, that such contracts be judged illegal as long as they have not been passed by the national parliament.

Provided that Iraq’s development and exploration policy can be implemented in an era free from current impediments, Iraq’s large oil resource base and its low finding and development costs should put Iraq’s oil industry on track for a major contribution to the world’s energy requirements in the 21st century.

The Petroleum Law

The central Ministry of Oil’s initial Petroleum Law draft aimed at a uniformity of policy and plans throughout the country.

It provides prior consultation with the provinces. Decisions taken at the center involve provincial participation. The supervision of oil and gas operations is shared between the provinces and ministry. The decisionmaking process has checks and balances to enhance transparency and anticorruption practices.

The overall objective is to optimize the oil and gas exploitation, maximize the return, and unite the country. It is based on Articles 111 and 112 seen in the light of Articles 2, 49, 109, and 110 of the constitution which broadly define the authorities and responsibilities of the federal and provincial authorities in the petroleum sector.

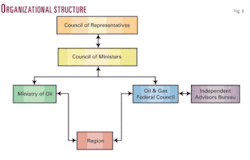

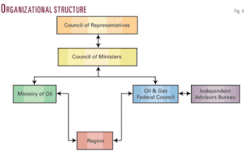

To achieve its objective, the draft petroleum law sets the authorities for existing and future organizational structures as given below.

Council of Representatives

- The Council of Representatives shall enact all federal legislation related to the crude oil and natural gas sectors.

- The Council of Representatives shall be the competent authority to sanction all international petroleum treaties related to petroleum operations that Iraq is a party to.

Council of Ministers

- Shall be responsible for proposing legislation to the Council of Representatives on the management of the management of the oil and gas resource.

- Shall formulate federal petroleum plans and policy and ensure its implementation.

- Shall administer the overall petroleum operations including the approving the federal policy, including exploration, development, and marketing, the proposal and the approval of relevant regulations.

- The Council of Ministers shall ensure that the Federal Oil and Gas Council and the Ministry of Oil adopt appropriate and effective mechanisms for consultation and coordination with the regional and producing governorate authorities.

Ministry of Oil

The ministry shall no longer carry out explorations or development and related operation. Its functions and responsibilities, however, will generally remain the same as previously but on advisory basis for the O&GFC approval and decision as shown below.

- Shall be the competent authority for proposing federal policy and legislation as well as issuing regulations and guidelines and undertaking the necessary monitoring, supervisory, regulatory, and administrative actions required to ensure the proper implementation thereof in accordance to the plans and policy of the O&GFC.

- Shall optimize the geographical distribution and timing of exploration and production programs and overall production and export level on the basis of proposals from the regions and producing governorates for the approval of the O&GFC.

- Shall prequalify IOCs, issue bids, and negotiate contracts based on the O&GFC models and policy and carry out technical accounting audits and other appropriate actions to verify conformance with legislation, regulations, contract terms, and internationally recognized practices.

Federal Oil & Gas Council

- The O&GFC shall decide on petroleum plans and policy for the exploration and development grant of rights and all proposals of the Ministry of Oil and ensure their proper implementation.

- Shall decide on model contracts and the exploration and development grant of rights among the national and international entities.

- Shall found the “Oil & Gas Federal Council,” O&GFC, which shall be chaired by the prime minister, and appoint its members as set out by the petroleum law.

- Shall found a think-tank and appoint its members to advise on all petroleum matters referred to it.

Independent Advisory Bureau

- Shall examine and provide comments and recommendations on matters referred to it by the O&GFC on the petroleum plans and strategic policy; grant of rights; development policy as well as key projects.

- Shall assess and provide recommendations on the grant of rights by the KRG prior to the enactment of the constitution in 2005 and assess all negotiated contracts by the region and the Ministry of Oil.

The regions

The regions, of which there is only KRG for the time being, shall have the authority highlighted below.

- Propose to the federal authorities activities and plans for the region to be included in the country’s plan for petroleum operations.

- Assist and participate with the federal authorities in discussions leading to the finalization of the federal plans and policies.

- Prequalify IOCs, organize their tendering process, negotiate, and initial oil and gas contracts for exploration and development blocks in areas under their jurisdiction using O&GFC model contracts for the approval of the latter.

- Approve the development plan of discovered fields and supervise its implementation, among other regulatory and supervisory roles.

- Be represented in the O&GFC.

Iraq National Oil Co.

The Council of Ministers shall submit a proposal for a law to establish the Iraqi National Oil Co. as an upstream holding company fully owned by the government and administratively and financially independent commercial company. INOC shall be authorized to:

- Enter directly into service and management contracts with qualified IOCs or service companies, if required.

- Operate some 26 currently producing fields, subject to the allocation by the O&GFC.

- Develop, produce, and operate some 25 discovered partly developed oil and gas fields, which are close to the currently producing fields, subject to the allocation by the O&GFC.

- Participate, singly or jointly with others, in exploration and development government tenders for fields other than those mentioned above.

- Manage and operate the main oil and gas pipeline system and export terminals.

- Establish fully owned subsidiary companies, among which there are already three operating companies.v Establish operating companies with others or own shares in companies inside and outside Iraq subject to the approval of the council of ministers.

- Enter into service and management contracts with qualified companies for the development of its oil and gas.

Need for INOC

Instituting INOC has proven a success in the past.

It built production capacity to over 3.5 million b/d from 1.5 million b/d in a few years and added oil reserves at the rate of more than 6 billion bbl/year in the 1970s.

As long as Iraq’s economy remains dependent on oil income, it is absolutely necessary to establish a national state-owned oil industry, which should be given the administrative and financial independence to command a pivotal role in the development of the country’s oil industry. It would ensure orderly exploration and developments (E&D) operations, decisions based on technical and commercial priorities, and optimum flow of income to the treasury.

- Large investment capital for future oil and gas development should not give credence to substituting national operation by IOCs. To build a production capacity of 1 b/d (365 bbl/year) costs around $5,000-10,000. The oil industry elsewhere was built by the IOCs through loans to the extent of 80-90% of the required investment capital. A borrowed capital of $5,000-10,000 to build a rate of 1 b/d of oil could be paid in less than 100-200 days of production in today’s market price. A bridge loan under such circumstances would be fairly easily obtained. And, the case would not be far different under a market of $35-40/bbl under such price eventuality. Thus, while capital investment for fast-track oil development coming from IOCs has credence, its benefit should not be exaggerated.

- Partnership on service contract with local content between the INOC holding a controlling interest and the IOCs is the best balanced policy option for expediting the building of Iraq’s oil industry to dimensions commensurate with its huge resource base. This is preferable to the disadvantages of sole operations of IOCs, regardless of contractual form. It provides transfer of technology and management and ensures orderly development and marketing oil export.

- Today, Iraq’s oil industry limitations inhibiting fast-track oil field capacity development (clearly, apart from the lack of security, instability, and absence of a government in full control of the country), are caused by insufficient oil experienced management personnel and the lack of up-to-date, state-of-the-art technology. An active INOC working jointly with IOCs on oil field development provides a solution to technology and management limitations and a balanced approach between total state oil monopoly and a free market controlled by IOCs.

- Growing dependence on IOCs, in a diminishing or absent role for INOC, deprives the state of economic independence and puts it at serious risk during circumstances when the IOCs’ obligations toward its shareholders or nationality might have to override Iraq’s national interest.

The stalled petroleum law

The Ministry of Oil presented its draft petroleum law to the Council of Ministers in September 2006. The council in turn formed a ministerial committee to examine the draft.

Ethnosectarian interests, expressed mainly by the KRG, not unsupported by sectarian interests, stretched out the negotiations for over a year and resulted in three revisions by the ministerial committee, with each in turn rejected by the KRG’s political leaders for one reason or another. It had made the enactment of the petroleum law subject to their agreement on the draft laws for the INOC, the organization of the Ministry of Oil, and the distribution of oil and gas.

Model upstream contracts

The Ministry of Oil is adopting four model upstream contracts that are based on the service-type contract formula, in exclusion of all the earlier PSA and buyback versions.

The draft models were recently used as a basis for discussions with ONGC Videsh, China National Petroleum Co., and Petrovietnam. The “Oilfield Service Development and Production Contract” (OSDPC) model was in fact adopted as the basis for the recent contract with CNPC. The four standard models are:

- Service Exploration and Production Contract (SEPC)

- Oilfield Service Development and Production Contract (OSDPC)

- Gas Field Service Development and Production Contract (GSDPC) <

- Producing Field Technical Service Contract (PFTSC)

Bidding parameters

For PFTSC, there are three parameters:

- Maintenance remuneration fee in US$ per barrel.

- Incremental remuneration fee in US$ per barrel.

- Enhanced Production Target in US$ per thousand barrels per day above a Baseline Production Rate.

For GSDPC, there are two parameters:

- Remuneration fee as per R-factor table in US$ (x) per barrel of oil equivalent.

- Final Production Target in MMscfd.

Cultural impact

Historically, the major international oil companies in the Middle East had established the largest industry, and at times the only industry, in any one oil-producing country.

They demonstrated a high degree of efficiency, unmatched in any one country. They became the largest provider of revenue to the state and gained great economic and political power. However, they formed distinctive enclaves, foreign and privileged and, thus, the terms ‘concession’ and ‘concessionaire’ developed controversial implications.

As a result, they became further associated with the colonial era, as the Middle East major oil producing countries were under direct or indirect foreign influence. Nationalization, therefore, was inevitable.

By the early 1970s the major producers of the Middle East pursued state monopolies over the exploration and development of their oil resources, while only a few were permitted partnerships with international oil companies. The return of the IOCs in Saudi Arabia has been limited to the E&P of gas, not oil, in Iran only under service contract of buyback terms, while in Iraq invitation to the IOCs, during the Saddam era in the 90s, took the form of production-sharing agreements and buyback contracts.

Iraq was no different from the majority in this respect as it established a national oil company (INOC) in 1964 and nationalized its oil industry in the early 1970s. Since nationalization, Iraq generally has known no mode of operation other than by INOC and-or its operating oil companies, occasioned by management service contracts.

Grant of rights: PSA vs. SC

Production-sharing agreements have wide and more favorable acceptance by most international oil companies and some host countries but have had a bad press in connection to their applicability in Iraq.

The PSA is generally very detailed, covering almost every aspect of the technical, fiscal, company role, and government regulatory and supervisory functions. It leaves little room for the state’s petroleum law to apply. Its term stretches to 30-40 years, without review. With such comprehensive details as decision-sharing, allocated production stream, and frozen terms, critics say it encroaches on the sovereignty of the state.

Partnership, as joint venture, on a service contract basis between the NOCs and IOCs is viewed in Iraq as the best balanced policy option. It provides the transfer of technology and management, eases capital investment requirement, and ensures orderly exploration and-or development and marketing, while it provides the option for IOCs to be paid in-kind.

A service contract, as the name implies, leaves the state’s sovereignty intact. It generally pays remuneration in cash, though crude oil purchase entitlement provides an option. As such, it is applicable to exploration and-or development. Provided it takes a joint venture model and integrate into the national interest through serious application of “local content,” it would no longer create an economic enclave isolated from the people and their economic interest.

Local content

The petroleum law views the petroleum resource as the inalienable and imperceptible property of the state.

In other words, petroleum is a nonrenewable depleting asset, meriting conservation, optimum fiscal reward, as well as, amongst others, providing a major role for the national oil company and requiring the adoption of a “local content.”

The draft petroleum law has not made the local content, in its wide context, a mandatory condition. However, the fact that other major producing countries such as Iran and Russia require 51%, which is on the increase, and Norway 70%, its adoption by IOCs should prove to be a rewarding policy.

Concluding remarks

As cited above, serious impediments take the shape of the manifestations of a failed state, insecurity and poor law and order, a weak and ineffective government, compounded by ethnosectarian politics, the absence of institutions and effective human resources, corruption, and lack of clarity in the constitution, contributing to the stalling the draft petroleum law, and the unilateral acts of the KRG in managing the oil and gas resource within the region without reference to the national government.

Provided that Iraq’s development and exploration policy can be implemented in an era free from current impediments, Iraq’s large oil resource base and its low finding and development costs provide sufficient incentive to override the present instability. It should put Iraq’s oil industry on a fast development track for a major contribution to today’s world energy requirements.

However, without a central unified policy there will be disharmony and competition between INOC—operating on production and marketing its export oil to provide the state’s income—and the regions and governorates—operating on exploration for unnecessary additional reserves—and among the various regions and governorates, with increasing disparity between the haves and have-nots.

While the draft petroleum law remains stalled, sound policy suggests that the Ministry of Oil should adopt its original draft petroleum law and abide by its articles, in particular the decisionmaking processes and the checks and balances therein.

This requires a high level decision to create the managerial and administrative entities mentioned above, or, if this is not possible, the Ministry of Oil should simulate such entities in order to gain credibility and support from the country’s oil industry unions and professionals, thinkers, and national politicians. The Ministry of Oil aims to pursue such route but has not achieved it yet.

For the Ministry of Oil, however, to carry on acting beyond an interim stopgap period and to continue with the grant of rights and vital projects on long-term execution of plans would be to commit the same mistake as that of the KRG, and to justify the KRG’s current policy.

The return by the KRG and other players to the principles of a united nation governed in peace and stability and adopting a federal model which enjoys the advantages of decentralization without the disadvantages of divisive ethnosectarian politics, would expedite the chances of moving towards a healthy state where the government is capable of managing effectively the affairs of the country and the nation.

Only then would Iraq’s petroleum law have the chance of a revival, provided that professional amendments are made and in the light of a positive constitutional revision.

Iraq’s deep-rooted civilization and the resilience of its people over many centuries remains the real assurance for the country’s eventual return to normality.

The serious impediments of the concessionary era ought to be eradicated. Old timers of the oil industry have learned their lesson from the concessionary period as economic enclaves isolated instead of being integrated in the community by way of joint participation and local content in service model contracts.

The national oil companies of this era have the bulk of the world’s reserves. They are the majors of the day whose contribution to their countries and to the global community is much enhanced through state-of-the-art of technology and management. The IOCs have and can provide both as services in exchange for cash or crude, which could well be the better model, under a culture which no longer should need IOCs or NOCs to replace either.

The author

Tariq Ehsan Shafiq is managing director of Petrolog & Associates, a petroleum consulting group since 1970, and chair of Fertile Crescent Oil Fields Development Co. (FOC), an Iraqi registered and Baghdad-based company since 2004. He is the coordinator and a member of a three-man consulting team entrusted with drafting a petroleum law for the Iraq Ministry of Oil. He has been working in the oil and gas industry worldwide and in various capacities for over 50 years and as a consultant for 37 years. He was a founder and director of Iraq National Oil Co. As the leading researcher at Petrolog & Associates, he coordinated preparation of four volumes on Iraq’s exploration potential, production capacity, and economics in a joint venture five-volume study, “Oil Production Capacity, Iraq,” with the Centre for Global Energy Studies (CGES). He has a BS in petroleum engineering from the University of California, Berkeley and was granted an honorary masters degree from Oxford University in 1980. He is a founding member and a trustee of the Oxford Islamic Centre and a fellow of St. Cross College, University of Oxford.

EgyptA group led by Vegas Oil & Gas SA, Athens, found oil and gas in Miocene Kareem sandstone at the Al Amir SE-2X appraisal well on the Northwest Gemsa Concession in Egypt’s Gulf of Suez onshore.

The well sustained 5,785 b/d of 41° gravity oil and 7.8 MMscfd of gas on a 1-in. choke from the lower of two identified pay zones.

Logs indicate a combined 42 ft of net thickness in the two pay zones. The upper zone, 22 ft thick, is to be tested later. Development planning is under way.

The 400 sq km concession lies 300 km southeast of Cairo.

Vegas Oil & Gas is operator with 50% interest. Circle Oil PLC has 40%, and Premier Oil PLC has 10%.

IndiaA group led by Quest Petroleum Pvt. Ltd. plans to explore onshore Block CB-ONN-2005/11 in the Cambay basin in India.

The 4-year exploration period calls for shooting 3D seismic and other geophysical surveys and drilling 15 exploration wells.

Block interests are Quest 20%, Quippo Oil & Gas Infrastructure Ltd. 40%, SRIE Infrastructure Finance Ltd. 20%, and Vectra Investment Pvt. Ltd. and Primera Energy Resources Ltd. 10% each.

Arrow Energy Ltd., Brisbane, signed a memorandum of understanding with state ONGC Ltd. of India to cooperate in coalbed methane.

At issue is potential cooperation on existing ONGC blocks from previous CBM license rounds in India and possible collaboration on Australian acreage. Commercial agreements are to be worked out.

ONGC provides more than 78% of India’s oil and gas production and holds the country’s largest hydrocarbon acreage.

KenyaOrigin Energy Kenya Pty. Ltd. will carry Pancontinental Oil & Gas NL, Perth, through a 3D seismic survey over the main prospects on Block L8 off Kenya under changes made to the L8 and L9 project status.

The L9 license will be relinquished, and as part of the revised exploration program accepted by the Kenyan government as a basis for granting a second additional exploration period on the L8 production sharing contract, the area of Block L8 will be reduced.

The retained portion will contain the main prospects, including the Mbawa feature sized at more than 5 billion bbl of recoverable oil or 7 tcf of gas, Pancontinental said.

By funding the seismic survey and all other project costs for the 2 years starting Jan. 22, 2009, Origin will earn 75% interest in L8 and Pancontinental will retain 25%.

Mbawa is 80 km off northern Kenya in 800 m of water.

TajikistanTethys Petroleum Ltd., Guernsey, Channel Islands, UK, began delivering gas to the town of Kulob, Tajikistan, from Khoja-Sartez gas-condensate field under a 1-year contract at $2.44/Mcf.

Initial volume is as much as 2.3 MMcfd. The gas is flowing through a 7.5 mile pipeline, and work on upgrading the gas delivery system is being considered.

Tethys is also working on three existing gas wells in Komsomolsk gas field near Dushanbe and plans to conclude a similar contract at a higher price due to greater demand. Gas for Dushanbe is currently shipped from Uzbekistan at $6.80/Mcf.

British ColumbiaProgress Energy Resources Corp., Calgary, combined in January 2009 from the former ProEx Energy Ltd. and Progress Energy Trust, set a budget of $340-360 million for the year, 40% of which is to be spent in the first half.

Progress plans to drill 30-35 wells in the Alberta Deep Basin in 2009, run four to six rigs in the Foothills of Northeast British Columbia, and drill four vertical and two horizontal Devonian Montney shale wells in British Columbia in the first half.

Gulf of MexicoThe Raton gas well in Mississippi Canyon Block 248 went on production near the end of 2008, said Energy Partners Ltd., New Orleans.

Flow has increased to 32 MMcfd of gas and 440 b/d of condensate. Noble Energy Inc., Houston, is operator of Raton and the nearby Redrock discovery in Block 204. The finds are in 3,300-3,400 ft of water.

Raton working interests are Noble Energy 67% and EPL 33%.

LouisianaDune Energy Inc., Houston, deferred drilling a fourth 2008 well in Garden Island Bay field in Plaquemines Parish, La., to reevaluate the risk-reward ranking of each prospect.

Dune signed an agreement with an undisclosed private oil and gas company. That firm, using its recently completed reverse time migrated 3D data set, will offer industry partners a 75% working interest in a 20,000-ft subsalt exploration prospect in a 4,900-acre area of mutual interest. Dune will keep the right to participate with up to a 15% interest.

Dune retained rights to all shallow potential, estimated at 130 bcfe in 15 prospects, and intends to drill three to five of the prospects in 2009.

Dune Energy is seeking an industry partner to participate in drilling a 13,400-ft prospect on the south flank of the salt dome at Bayou Couba field, St. Charles Parish, La.

Dune would keep a 25-40% working interest in the prospect. Drilling would take place in the first half of 2009.

Further work is planned on depth migrating the 3D data set to further define a subsalt exploratory prospect slated for drilling in late 2009.

Texas-WestSandRidge Energy Inc., Oklahoma City, is negotiating to sell its midstream assets in Pinon gas field in the West Texas overthrust.

The transaction is valued at $500 million in cash proceeds and reduction in midstream capital spending, the company said. With the planned asset sale and a private placement, the company plans to hike its 2009 capital budget to $700 million from $500 million.

Production guidance for 2009 would rise to 115-120 bcfe from the previous 110 bcfe, and the company expects the planned increase will allow it to load the first phase of its Century carbon dioxide separation plant in 2010 (OGJ, Nov. 28, 2008, p. 34).

Production averaged 274 MMcfed of production in 2008 and ended the year at 325 MMcfed.

WyomingAmerican Oil & Gas Inc., Denver, reported a completion in Cretaceous Frontier of a well in Fetter field in Converse County, Wyo., and said it may recomplete this and other wells from the Frontier and Niobrara formations.

Sims 7-25, in 25-33n-71w, flowed to sales at the rate of 1.427 MMcfd of gas and 86.7 b/d of oil on a 24-hr test with 2,540 psi flowing tubing pressure on a 12/64-in. choke.

Drilled and completed for $2.9 million, it underwent different completion and frac design than earlier vertical wells in the field, the company said.

American’s working interest in the well is 69.375%.