International upstream: a 5-year roller coaster

Investors in the upstream oil and gas industry have been on a roller coaster ride for the past 5 years, with prices reaching dizzying heights and then plummeting. The latest twist on the roller coaster leaves operators with a cost base and tax rates reflecting a price environment that seems to have disappeared. Consequently, company profits are evaporating, and there is huge pressure on future investment plans.

Governments of oil-producing countries are hurting, too. With the oil price dropping (and operators' costs increasing), governments' tax margins have been squeezed dramatically. Some governments have reduced their projected levels of oil revenue, impacting the budgets that they established during the previous fiscal year.

International agreements Relationships between oil and gas companies and host-country governments have come under strain. This article examines pressures resulting from recent gyrations in the price of crude oil. Following it, on Sept. 7 and Sept. 14, will be a two-part look at the evolution of international petroleum agreements. |

With the added shadow of global credit restriction, governments and investors face tough decisions as they prepare for the next twists on the roller coaster. Which fiscal measures are governments likely to consider in dealing with the unexpected dip in their oil revenues? What impacts are these measures likely to have on investor and government revenues? And which fiscal regimes are most likely to produce a more stable outlook for governments and investors alike during the present downturn and beyond?

No surprise

Increases in tax rates as oil profits soar might not be welcomed by investors, but they can hardly come as a surprise. Investors would also expect tax rates to come back down when prices fall to encourage investment and maintain production levels.

There has been some evidence of governments, notably that of Russia, beginning to reduce the tax burden, and there is a growing expectation that more will follow with time. The questions investors are asking are when will tax rates fall, and by how much?

Several countries recently introduced windfall taxes that were constructed in such a way that tax rates reduce automatically when prices fall. These levies are generating much less revenue at current prices (Fig. 1).

Another feature of recent increases in the government take, however, was for governments to target revenues rather than profits by increasing royalty rates, increasing export duties, or lowering cost-recovery ceilings. These measures can raise the percentage of government take from the gross operating margin (Fig. 2).

Following the oil price crash in 1986, many governments responded by reducing or even abolishing royalty rates and other regressive fiscal terms. This response will once again be a focus for investors in discussions with governments during the current downturn. But because royalty is based on revenue rather than profit, some governments may actually be tempted to increase rates rather than reduce them. US Interior Sec. Ken Salazar, for example, has recently announced a review of federal royalty rates, noting that other countries charge higher royalty rates than the current US range of 12.5-18.5%.1

Another feature of the government response to the mid-1980s price crash was the reconfiguration of several fiscal regimes to make the level of fiscal take more sensitive to project profitability than to revenues. Regimes following this strategy have proven to be quite responsive during recent price increases. But, as the experience of Angola shows, where the government take is linked to a project's rate of return there is no inherent mechanism for reducing high tax rates when prices come down unless the cash flow becomes negative (Fig. 3).

Very high marginal rates applied to greatly reduced margins are likely to discourage operators from continuing to invest in projects and, in extremes, may even make projects uneconomic. Moreover, there is little incentive for operators to reduce costs.2

Start again?

Even where government and investors are aligned in their desire to change terms to suit the new economic environment, a regime ensconced within a contract will require renegotiation. But contractual instability has been portrayed as anathema by investors in recent years. Countries that changed terms unilaterally were accused of demonstrating the worst kind of investment risk. And some have suffered from reduced investment as a result.

A government's willingness to improve terms sends a more favorable message to investors—apart from those which believe contracts should remain intact even if they were to benefit from a change. In some countries, however, renegotiating contract terms carries an additional element of reputation risk.

With prices high, several countries took advantage of the industry's appetite for prospective acreage by allowing companies to bid for blocks based on fiscal terms. Some of the winning bids in North Africa, in particular, attracted extremely aggressive production-sharing bids. The current environment lowers chances that investors can make an economic return under these terms, creating a major obstacle to investment.

These governments are now caught between a rock and a hard place. Either they agree to reduce the take in the contract—invalidating the auction process at the same time—or they force the contractor to stick to its obligations, which it cannot afford to do. This results in forced relinquishment and retendering, all of which delays investment.

How low?

Governments which are free to reduce tax rates for upstream investors at will—including most countries that belong to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development—may decide not to do so. Lower prices are already reducing expected tax revenues from upstream operations. And the general economic downturn is reducing tax revenue from other industries. Where the government is reliant on oil and gas income, this can create budget deficits, forcing governments to reduce commitments to social projects.

Spurred by last year's surge in oil prices, several governments set budgets for 2009 based on prices' remaining relatively high. These budgets are now being heavily revised. For example, Alaska has reduced its 2009 revenue expectations by $2 billion, resulting in the cancellation of $1.2 billion of planned savings, a reduction in planned expenditure of $300 million, and a draw on savings to balance the 2009 budget.3

Alaska is, however, able to draw upon budget surpluses built up over recent years, an ability it shares with several countries that generated budgets based on modest price expectations.

Others have been less prudent. Stories are beginning to emerge of national oil companies in oil-dependent countries reneging on payments to suppliers and other contractors, resulting in postponed and canceled work. This makes politicians vulnerable, a consequence of which might be that the government will look to the oil industry for more money and actually increase tax rates, despite project economics being on the downward slope.

Governments point out that the most recent oil company accounts show record profits (based on last year's high oil price). They also observe that major oil companies are reporting, on average, ongoing production costs between $6/boe and $12/boe.4 So they conclude that there is still ample profitability in the industry, which thus becomes an easy target for higher taxes.

The recent US budget proposals provide a good example of a government seeking to raise additional tax revenue ($31 billion) from its upstream industry despite the low-price, high-cost environment. These proposals have been accused of exacerbating already low investor confidence in US activity, which is suffering from the combination of tight credit availability and lower commodity prices. Drilling activity in the US has plunged (Fig. 4).

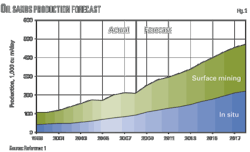

Targeting existing production profits for additional tax revenue overlooks the need for a large proportion of those profits to be plowed into ongoing capital expenditure to maintain existing production levels and develop new sources of production. The full-cycle costs of such investment greatly exceed ongoing production costs. For some of the more complex major sources of new production, such as Canadian oil sands and deep water, recent cost increases have pushed the full-cycle costs to near the current oil price, and projects are being postponed as a result. In mature basins, the small size of new fields results in much higher unit capital and operating costs than prevail for legacy assets. Even the lowest-cost countries of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries say they cannot invest at $40/bbl and late last year postponed projects, although some revived projects when crude prices returned to $70/bbl and costs declined.5

And that is the crux of the matter: Can governments afford to increase taxes on existing production, gaining short-term revenue but running the risk of reduced investment and reduced revenue in the future? On the other hand, can they afford to reduce taxes now to stimulate investment?

Fiscal twists…

Thus, governments of all oil and gas producing countries face a short-term dilemma with long-term implications: Should they increase or decrease the level of their take? A number of factors influence this discussion:

- Attitude toward investors.

- Perception of industry costs.

- Perception of future opportunities.

If the attitude toward investors is generally favorable and open, governments (such as Indonesia and Norway) which have held fiscal terms stable through the roller coaster's recent upward climb may be expected to remain stable in the downturn. Others, which have demonstrated in the past that they will increase or decrease tax rates as conditions change, might reasonably be expected to undo some of their recent tax increases (such as the UK).

On the other hand, countries that experienced a surge of resource nationalism during the upturn face a quandary. They now have a large stake in many projects which are rapidly losing value and which, in many cases, require substantial additional investment. As the funding of these projects reduces the government's ability to fund social projects, there will be conflicting demands on a thinner purse. Capital investment in oil and gas projects in these countries could dry up, reducing future production levels and allowing the vicious cycle to continue.

In the past, this has resulted in governments' renewing opportunities for the private sector in new investment, ideally including a carry of the state's equity. But a number of major obstacles stand in the way of this process in the near future:

- Citizens and politicians had just become accustomed to being resource owners and minimizing the role of the private sector. It is too soon to begin to climb down from that position.

- The number of private investors with access to capital to fund the investments has fallen dramatically.

- Those companies that remain well funded will view any opportunities with great caution and anxiety, following the investment instability of recent years.

Thus, inviting the companies back in may not be easy. In fact, some governments have suggested they may even go the other way and nationalize the industry in order to remove completely any remaining private sector profit. But even if governments do decide to work more closely with oil companies, any fiscal incentives that they offer are not guaranteed to generate investment, and they might be regarded as not worth the paper they're written on if terms have been radically altered in the recent past.

…And turns

Governments are perturbed by the high levels of cost inflation in the industry. While prices were also rising they could mostly live with it, but now that prices are much lower governments' attention is turning to these costs as a source of depriving them of revenue.

A number of moves have been proposed that will cap, reduce, or even disallow certain costs from being recovered from revenue. Thus, tax rates can be left alone, but the tax base is increased along with government revenues. Alaska, for example, introduced a cap on Prudhoe Bay operating expenses in its 2007 tax changes, and the recent US federal tax proposals increase the depreciation period for drilling expenditure.

The message that normally accompanies such proposals is that the oil industry is enjoying certain incentives which are no longer merited. But the industry regards these as necessary to balance the extremely high risks, capital intensity, and long delivery times of oil and gas projects, all of which make them different from big investment projects in other industries.

In addition, oil and gas projects are normally subject to a variety of other fiscal levies that are not applicable to other industries. So any beneficial treatment in the standard tax terms may be viewed in part as compensation for this. Ultimately, however, the main point is that reductions in cost allowances—particularly those related to exploration and development expenditures—will reduce investors' returns and possibly decrease investment.

Some countries are also seeking to reduce cost allowances for tax while taking the opportunity to create incentives for local content by restricting deductions to costs incurred outside the country. Nigeria's 2008 Petroleum Industry Bill, for example, proposes the restriction of deductible overseas expenditure to 80% of the total amount spent. Kazakhstan has also proposed updating existing contracts to make purchasing from local suppliers mandatory rather than simply allowing oil companies to purchase locally when they can.

This fiscal targeting of costs adds to operators' need to take back control of the supply chain and reduce costs. The message that operators are sending to suppliers is quite clear: "The price has gone back down to 2004 levels, and so should your rates." But how quickly they can achieve their goal remains to be seen. Many current contracts have been signed on a multiyear basis, based on rates that were at an all-time high. Companies trying to renegotiate or simply reneging on these contracts will be guilty of the same charge they have made of some governments in recent years: disregarding the sanctity of contract terms.

Is stability achievable on the fiscal roller coaster?

Any fiscal system needs to cater to a wide array of project economics, from existing production in legacy fields and incremental investment in these fields to maintaining production through to wildcat exploration in frontier areas. Even without a volatile price and cost environment, the range of risk-reward profiles in most countries is vast. Consequently, trying to apply one set of fiscal rules to all projects is unlikely to succeed, as is any attempt to apply lower or higher taxes across the board.

Governments and investors seeking to achieve stability on the fiscal roller coaster will need a flexible set of terms that acknowledge (a) the government's demand for a high share of profits when economics are robust and (b) the investor's need for incentives to maintain investment in more difficult situations.

Key principles

Some of the key principles that governments should consider when revising fiscal regimes are as follows:

- Tax rates that respond automatically to price changes—such as price-linked windfall levies—are far more likely to create an investment environment without ad hoc fiscal changes than flat tax rates.

- Fiscal terms levied on project profits rather than on revenues are less likely to result in developments being postponed or production being brought to a premature end on marginal fields.

- Focusing fiscal incentives (such as capital allowances) on incremental investment in older, producing fields for tax purposes provides an incentive to continue investing in these legacy assets. Producers which are not reinvesting profits from such production will then be subject to higher effective tax rates than those which are continuing to invest.

- Increasing local content could be helped by adding an uplift allowance to these costs but not by disallowing costs spent overseas, which may be the only source of appropriate equipment.

There are many peaks, troughs, dips, and twists yet to come on the fiscal roller coaster. It remains to be seen which governments will work with investors to keep investment on the track.

References

- "US to consider raising oil, gas royalty rates," Reuters, Mar. 24, 2009.

- See Wood Mackenzie, "Fiscal Storms Perspective," May 2008, and "Cost Hyperinflation Global Insight," July 2006.

- Governor of Alaska press release No. 09-17, Feb. 3, 2009, (http://gov.state.ak.us/archive.php?id=1621&type=1).

- BP Strategy Presentation, London, Mar. 3, 2009, www.bp.com/liveassets/bp_internet/globalbp/STAGING/global_assets/downloads/I/IC_bp_strategy_presentation_march_2009_slides.pdf.

- Petroleum Economist, Energy Report, Mar. 18, 2009.

The author