Special Report: Study estimates costs of CO2 emission controls on oil sands

New controls on emissions of greenhouse gases will raise the costs of petroleum supplied from oil sands by amounts that depend on the extent of regulation and on progress in abatement technologies.

The extra emissions associated with oil sands have attracted intense environmental scrutiny and spawned efforts to limit consumption of products derived from bitumen.

According to a report on the Canadian oil sands published in May by the Council on Foreign Relations Center for Geoeconomic Studies, the average, life-cycle greenhouse gas emissions associated with a barrel of oil sands crude exceed those from the average barrel of oil consumed in the US by about 17%.

The study, by Michael A. Levi, CFR David M. Rubenstein senior fellow for energy and the environment, projects costs to producers and refiners of conventional and unconventional crude oil at various prices of emitted carbon.

Comparing emissions

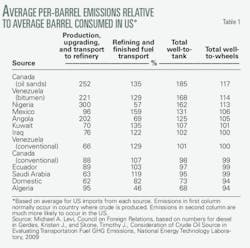

The extra emissions associated with oil sands come mainly from production and upgrading, Levi points out.

The average emissions from these operations in the oil sands are nearly three times those of the average barrel of oil consumed in the US.

But emissions vary among oil sands projects. Levi cites a recent RAND study that found greenhouse-gas emissions from production and upgrading of oil sands range from 70 kg/bbl to 130 kg/bbl—10-20% more than the average barrel of oil consumed in the US.

Emissions from oil sands would increase with a shift in process fuels from natural gas to coal or raw bitumen; they would decrease with technological improvements.

“The latter trend has recently dominated,” Levi says.

The analyst also points out that average emissions vary with crude type (Table 1).

He says the extra greenhouse-gas emissions associated with Canadian oil sands relative to conventional oil at the current production rate, about 1.2 million b/d, represent about 5% of Canada’s total emissions, 0.5% of US emissions from energy use, and 0.1% of global emissions.

If production increases as expected with no improvement in per-barrel emissions, the contribution to Canadian emissions will triple by 2030. But the increment relative to US and global emission will still be minor.

If policies slash emissions from other sources to the extent necessary to meet ambitious goals set to abate global warming, however, “the relative prominence of the oil sands would greatly increase,” Levi says.

Increases in emissions related to an expected rise in oil sands production to a plateau of 4.2-4.3 million b/d in 2030, coupled with emissions cuts in the US and Canada of 80% by 2050, would make oil sands responsible for about 10% of US emissions and nearly all of Canada’s emissions at midcentury.

“Oil sands’ emissions will thus be critical to deal with in the long term though not as important in the immediate future,” Levi says.

The cost

A central question thus is the cost of lowering greenhouse-gas emissions from oil sands production and upgrading.

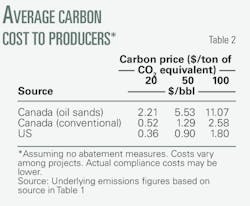

Levi estimates costs to producers of oil sands and conventional oil, assuming no abatement measures, based on carbon prices of $20/ton, $50/ton, and $100/ton of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e) (Table 2).

A carbon price of $20/ton of CO2e is about the level in effect in Europe and what is expected to result from a cap-and-trade scheme or carbon tax in the US. The price probably would rise toward $50/ton of CO2e in 2020-30 and continue to rise after that.

Levi points out that projected carbon costs for oil sands are small relative to the expected price of oil and says, “This is in stark contrast, for example, with coal-fired power, whose cost would increase sharply even for modest carbon prices.”

He adds, “Carbon costs could affect production and pricing at the margin, and very high carbon prices in the near term could have much larger impacts.”

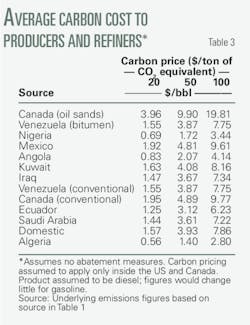

Levi also estimates the average carbon cost to producers and refiners for a range of crude oils, assuming that Canadian and US producers face carbon costs throughout the operational chain and that others face carbon costs for refining and final distribution in the US.

He notes that while the refining increment roughly doubles the cost of Canadian sources, it adds to other oils as well.

“Whether this extra cost will be absorbed by producers (through reduced production or lower profits), by refiners, or by consumers (through higher prices) depends on the finer details of refining and product markets and is extremely difficult to predict,” Levi says. “The possibility that the impact of carbon pricing will be larger than what is indicated in Table 2 is, nonetheless, impossible to dismiss.”

“Carbon costs could affect production and pricing at the margin, and very high carbon prices in the near term could have much larger impacts.”

Michael A. Levi, senior fellow for energy and the Environment, Council on Foreign Relations

Policy recommendations

Levi made his cost observations as part of a study, The Canadian Oil Sands: Energy Security vs. Climate Change, that included policy recommendations. He said a US strategy for the Canadian oil sands that balances climate change mitigation with security interests should combine these elements:

- Link US and Canadian cap-and-trade systems. The aim, Levi said, should be “fair and stable carbon pricing in Canada.” The US should ensure that Canada is able to provide a small number of free emission permits to oil sands producers, he said. Doing so would both lower the risk that carbon pricing would raise world oil prices and maintain incentives for oil sands producers to cut emissions.

- Tread carefully with any low-carbon fuel standard. Any requirement for specific cuts in average emissions from transportation fuel should not penalize oil sands, which already will carry a heavy burden of carbon costs.

- Focus US technology support on higher-payoff areas. Government assistance for carbon capture and sequestration (CCS) and nuclear power for oil sands “would generally not be US dollars well spent,” Levi said. Government-funded innovation instead should focus on CCS for power plants, renewable fuels, transmission, and efficiency.

- Resist the misuse of other US environmental regulations to constrain oil sands. “So long as the oil sands are expected to face a fair and reasonable carbon price, the United States should resist attempts to use US environmental regulations to block permitting of oil sands-related pipelines or refineries on climate grounds,” Levi said. Similarly, the US should not use regulations to indirectly address social and environmental effects of oil sands work in Canada.