Uruguay, with no current oil and gas production, has completed the qualification step of its first offshore bid round, offering 11 continental shelf blocks that drew interest from six operators.

The Administracion Nacional de Combustibles, Alcohol y Portland (ANCAP) opened the 2009 Uruguay Round last year and adjusted terms in March to reflect the slump in global oil and gas prices.

On May 6 the government said ANCAP is evaluating information submitted from BHP Billiton, Galp Energia SGPS SA of Portugal, Petroleos de Venezuela SA (PDVSA), Petrobras of Brazil, and Pluspetrol and YPF SA of Argentina. Qualifying companies will be able to submit bids.

This article presents a general background of Uruguay’s hydrocarbon industry and its position within the Latin American context. It then discusses the main fiscal terms of the contracts on offer.

Seeking alternatives

Uruguay has not been a major target for international energy companies looking for prospects abroad. This small South American country, neighboring Argentina and Brazil, has no current oil or gas production. It has been meeting its energy needs with imports, particularly natural gas from Argentina, to which Uruguay is connected by two natural gas pipelines, the Gasoducto del Litoral and the Gasoducto Cruz del Sur.1 Since Argentina started cutting its exports, Uruguay has been exploring alternative sources to cover its energy needs.

These alternatives include a proposed LNG regasification facility at Montevideo. Earlier this year, the Uruguayan Ministry of Industry, Energy, and Mines (MIEM) announced a tender for construction of the Montevideo LNG Plant, which would use a floating LNG tanker with an initial capacity of 3-4 million cu m/day.2

The Uruguayan government seems keen to pursue this project to fruition and continues studying its feasibility and structure.

Safe haven

In comparison with some of its neighbors, Uruguay represents a safe haven for international investments.

International oil companies (IOCs) venturing into Latin America are justifiably concerned about contract stability and creeping expropriation, having witnessed, or fallen victims to, resurgent resource nationalism.

A wave of nationalistic moves started in 2006 when the administration of Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez required the conversion of operating service agreements, executed by IOCs with previous governments under the Apertura (opening), into mixed companies majority-owned and controlled by the Corporacion Venezolana del Petroleo (CVP), an affiliate of PDVSA. The companies now must sell all hydrocarbon production exclusively to PDVSA.

Bolivia came next with President Evo Morales’s issuance of a nationalization decree on May 1, 2006, and subsequent execution of operations contracts between IOCs and the state oil company, Yacimientos Petroliferos Fiscales Bolivianos (YPFB), in which YPFB retains ownership of produced hydrocarbons and full control over their commercialization.

In October 2007, Ecuador’s President Rafael Correa imposed a windfall profits tax whereby the government keeps 99% of oil profits, changing the previous law that called for 50-50 sharing with foreign oil companies of profits from rising oil prices. This tax is still in place despite the decline in oil and gas prices.

Argentina has not resisted this nationalistic fervor. Populist governments have capped natural gas prices, keeping wellhead prices far below international market levels. The restriction has discouraged upstream investment and created shortage.

Resource nationalism has not taken ground in Colombia, Peru, Brazil, or Chile, which continue to offer attractive terms and contract stability to foreign oil investors.

Chile, in fact, shows how a country with no history of hydrocarbon production and heavily reliant on imports (98% of the crude oil it needs, 96% of the coal, and 75% of the natural gas) has been able to attract foreign investment to exploratory opportunities.3 The country’s last bid round, held in June 2008 for the Magallanes basin, resulted in the award of eight blocks. Three of the blocks involve participation of state-owned Empresa Nacional del Petroleo (ENAP) in 50-50 joint ventures with the selected contractors–Pan American Energy, Greymouth, and Apache. Blocks with no ENAP participation went to IPR Mans, Apache, and Greymouth Petroleum (two).

Uruguay thus is trying to join the safe-haven list of Latin American countries with its offshore bid round offering attractive commercial and fiscal terms to IOCs.

From the standpoint of political stability, Uruguay ranks in the top 75-90 percentile range, according to World Bank Governance Indicators.4 It ranks first in Latin America for lowest corruption, first for judicial independence, and second in South America for protection of property rights.5 6

Uruguay also has a solid track record of respecting foreign investment, with not a single case filed against it before the International Center for the Settlement of Investment Disputes. It is a party to numerous bilateral investment treaties (BITs), affording protection to foreign investment in the form of national treatment, most favored nation treatment, and restrictions on expropriation or nationalization requiring prompt, adequate, and effective compensation. It has signed 29 BITs with countries including the US, Canada, the UK, France, and Spain.7

Bidding procedures

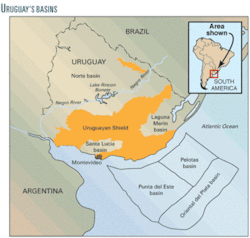

ANCAP will accept bids from qualifying companies for the award of production-sharing contracts for 11 blocks comprising a total surface area of 74,000 sq km in the Punta del Este, Pelotas, and Oriental del Plata basins.

The areas have been the subject of geological, geophysical, and geochemical study through surveys commissioned by ANCAP. According to ANCAP’s technicians, many leads and plays have been identified in shallow to ultradeep water, some of them analogous to productive systems elsewhere in the Atlantic.8 Seismic records include bright spots–amplitude patterns that may indicate the presence of natural gas.9

Prospective bidders had to prequalify by Apr. 30, producing evidence of compliance with legal, financial, and technical criteria. Prequalified companies may then bid for any number of areas provided an independent bid is submitted for each. The term for submission of bids by prequalified companies is scheduled for June 14-July 1. The blocks will be awarded according to the following factors:

- Minimum work program.

- Economic terms, including:

- the maximum percentage of production requested for cost recovery,

- the profit-sharing percentages per type of hydrocarbon and levels of accumulated production, and

- the increase of ANCAP’s sharing percentage for hydrocarbons price increments.

- Maximum participation allowed for ANCAP in any exploitation lot of 20-40%.

Main fiscal terms

The Uruguayan PSC provides for an exploration period of 4 years, during which the contractor must carry out the minimum work program. The contractor has the option to extend the exploration period by 2 years.

The exploitation period is 25 years, subject to a maximum PSC term of 30 years. The contractor may request a 10-year extension.

As in many PSCs, the contractor’s remuneration under the Uruguayan agreement includes cost-recovery and profit-sharing elements.

The cost recovery portion reimburses exploration, development, and production costs incurred by the contractor.

The basic profit-sharing split, with the stipulated range of 20-40% for ANCAP, depends on the contractor’s bid. ANCAP’s share is subject to an increase linked to increases in the prices of oil and gas over base levels, the percentages being matters of bidding.

Contractors may export their shares of production, subject to a preferential right of ANCAP to purchase all or part of the hydrocarbons as necessary to satisfy domestic needs. ANCAP may request that the contractor sell its share of hydrocarbons.

The government charges no royalties and exempts PSC contractors from taxes and levies other than the tax on the income from business activities (TIBA).

Further, acknowledging the decline of international crude prices and consequent cuts by IOCs to exploration budgets, ANCAP eased the terms in March, eliminating the requirement for the drilling of at least one well during the exploratory period for certain blocks and leveling the exploration guarantee at 10% of the minimum exploration program.10

Other terms

The PSC attempts to assure the contractor of fiscal stability through a cost-reimbursement mechanism. Under this provision, any new taxes and levies taking effect after signing of the PSC and any changes to the TIBA that increase the contractor’s burden can be treated as recoverable costs.

If a PSC yields a discovery warranting development, ANCAP has the right to participate in the exploitation phase. If it decides to participate, its notice to the contractor must include the percentage it will acquire, ranging between 20% and the maximum percentage indicated by the contractor in its bid.

ANCAP’s participation is subject to its payment to the contractor of an amount equal to its interest in the direct drilling and completion costs of the exploration wells in production. For appraisal wells, ANCAP must pay the contractor its participating-interest share of all direct expenses plus 15% to cover indirect expenses. However, no costs are reimbursed for appraisal wells less than 25% productive.

Effect of slump

Given the country’s history of political and legal stability, Uruguay may be an attractive destination for foreign investment in energy ventures.

ANCAP has been actively promoting the 2009 Uruguay Round, including road shows in Houston and London.

A major challenge for the 2009 Uruguay Round stems from global economic problems and budget cuts by companies responding to a slump in oil and gas prices. However, in times of crisis, companies that take advantage of good investment opportunities can position themselves to fare better than their competitors in the long term.

References

- US Energy Information Administration, Country Analysis Briefs.

- Oil & Gas News, BNamericas, Jan. 13, 2009.

- Ministry of Minerals, Chile.

- World Bank Worldwide Governance Indicators, 1996-2007, http://info.worldbank.org/governance/wgi/sc_country.asp.

- Transparency International.

- World Economic Forum.

- International Center for Settlement of Investment Disputes.

- ANCAP.

- Press release on worldoils.com, Dec. 28, 2008.

- Ministry of Industry, Energy, and Mines, Decree 845, Mar. 30, 2009.

The author

Maria Victoria Vargas concentrates her consulting practice in international oil and gas. She has experience advising companies conducting hydrocarbon exploration and production, particularly in Latin America. She holds a JD degree with honors from the Universidad del Rosario (Bogota) and an LLM from Harvard Law School. Vargas is admitted to practice law in Texas and New York and in Colombia. She is a Colombian national, fluent in Spanish and English, and member of the Association of International Petroleum Negotiators (AIPN). Based in Houston, she can be reached at [email protected].