Gazprom pipeline gas remains key to Europe

Europe will have to work with Gazprom to develop the supplies and transport routes to meet projected natural gas shortfalls, as increased European LNG receipts and such pipelines as the Trans–Sahara are unlikely to provide timely relief. The Europe–Gazprom relationship is mutually beneficial and the current economic downturn should place a premium on the importance of working together.

Background

The recent interruption of natural gas supplies to Ukraine by Gazprom stirred discussion of the company’s reliability as a major supplier to Europe. Memories of similar events just 2 years before magnified these concerns. This article will analyze the foundations for these concerns, looking closely at transportation routes, availability of supply, and Gazprom’s financial ability to pursue either new routes or new supplies.

Gazprom will do its best to supply Europe because the European Union (EU) is its largest and best paying customer, but a number of considerations will affect its ability to do so:

- Europe will continue to diversify its gas supply sources (mostly via LNG and storage) but even while doing so will continue to depend on Gazprom for a large portion of its natural gas.

- Although the amount of Russian gas shipped to Europe will likely increase, its share of overall European gas imports will decrease.

- In the medium to long term, Europe will face a natural gas supply gap (151 bcm/year in 2020, according to EuroGas), requiring it to worry about the availability of Russian gas beyond the volumes currently supplied. Several factors could limit the availability of extra supplies to Europe.

—Gazprom will continue to diversify its export options, building on current plans for a pipeline to China and for LNG projects.

—Russian domestic demand for gas will likely rebound to a healthy growth rate (0.5–1%/year) despite the loosening of price controls. The new pricing environment will offer Gazprom a more attractive market.

—Central Asian producers may divert supplies away from Gazprom; e.g., eastward to China.

—Gazprom’s and independent producers’ investment in upstream and transportation segments, though sufficient to meet existing contracts, falls short of what would be required to supply Europe in the long term.

Understanding dependence

Europe is concerned Gazprom will dangerously increase its share of European supply. A closer look at projected numbers, however, shows a drop in Gazprom’s share of European imports.

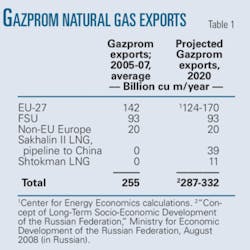

Russia exported an average of 255 billion cu m/year in 2005–2007, including 142 billion cu m to the EU. Recent Russian government forecasts, however, project Russian natural gas exports of 287–332 billion cu m/year by 2020.1 This outlook includes Sakhalin and Shtokman LNG export commitments and pipeline deliveries to Asia, particularly China, all of which would amount to about 50 billion cu m/year under the inertial (basic) scenario (Table 1).

By 2020 the EU can expect at most about 170 billion cu m/year from Russia, only 28 billion cu m/year more than the current average. In the worst case scenario, only 124 billion cu m/year of Russian gas will be available to Europe, 18 billion cu m/year less than the current average.

For simplicity, these estimates assumed exports to the FSU and non–EU Europe would stay at current levels and Russia would not further diversify its pipeline and LNG export options beyond Sakhalin, Shtokman, and a pipeline to China. Any increase in these alternatives would further reduce the amount of gas available to the EU.

Predictions call for EU demand to increase roughly 20% by 2020 to 688 billion cu m/year according to a EuroGas study,2 while indigenous production falls to 198 billion cu m/year (Table 2). The study projects a deficit of 151 billion cu m/year after domestic production and planned imports.

The same study projects an increase in EU dependence on suppliers outside Europe to 68% in 2020 from 41% in 2005. Gazprom’s share of EU gas imports could be reduced to 35% in 2020 from 51% in 2006, under the most conservative case, and to 25% the least conservative case.

According to the EuroGas study, 151 billion cu m/year of the needed 490 billion cu m/year of imports projected in 2020 were not under long–term agreements yet. Plausible options for closing this shortfall include increasing pipeline supply from North Africa, increasing LNG imports, signing new contracts with Gazprom (and helping with whatever infrastructure development might be necessary), or developing non–Gazprom supply routes from the east, such as Nabucco.

Transportation routes

In its effort to diversify supply sources, Europe has studied various alternatives, including expanded LNG receipt capacity and increased storage capacity (so that more natural gas, particularly LNG could be stored for winter months). The Nabucco pipeline is another studied alternative. Although the economics of the project are difficult, the recent shutoff of supplies by Gazprom has reinvigorated the political desire to complete this pipeline.

Nabucco is supposed to deliver 31 billion cu m/year of natural gas from the Caspian region, potentially including Iraq and Iran, to Central Europe via Turkey. Several potential problems, however, continue to surround the project.

Not only would the Nabucco partners compete for supply against Gazprom, China National Petroleum Corp. (CNPC) and quite possibly India’s Oil and Natural Gas Corp. (ONGC), Nabucco’s value to Caspian producers has also been diminished by recent long–term contracts between Gazprom and Central Asian producers based on netback pricing formulas.

The chances of filling Nabucco with gas from Iran as an alternative are limited. It remains politically difficult to conduct long–term business with Iran. The country also seems to lack not only sufficient supply but also the necessary upstream and transportation investment to make connection to Nabucco viable.

Gazprom supports two other alternative pipelines: South Stream under the Black Sea and Nord Stream through the Baltic. Gazprom anticipates these routes will protect it, and presumably European customers, from unauthorized withdrawal of gas by transit countries such as Belarus and Ukraine and delayed payments. Gazprom is also using these pipelines (especially South Stream) to preempt Nabucco or other pipelines that would bring Caspian supplies to Europe.

The onshore portion of Nord Stream is under construction in Russia, but the project faces resistance from some EU members. Germany and Sweden raised ecological concerns regarding the project. Poland and the Baltic states, meanwhile, have voiced their preference for an onshore pipeline instead.

Russian supply

Even if the Nord Stream, South Stream, and the other routes are built, can Gazprom fill Europe’s import gap?

The only two projects currently under way are Sakhalin and Shtokman, targeting Pacific and Atlantic markets, respectively. In the Atlantic Basin, natural target markets for Shtokman LNG include the Iberian Peninsula in Europe, virtually disconnected from the broader European natural gas network, and LNG regasification terminals on North America’s East Coast.

Gazprom affiliate Gazprom Marketing & Trading (GMT) has already signed a preliminary memorandum of understanding with Spain’s Gas Natural for LNG deliveries, expected to be executed at first on a swap basis similar to previous deliveries to the US, Japan, and Korea.

In North America, Gazprom has secured sales to the Rabaska LNG terminal in Canada. The North American LNG market, however, has so far been lower priced than those in Europe and Asia. Uncertainty has also grown regarding the medium–term supply–demand balance in the US and Canada. Unconventional gas plays in the region have proven to be economically feasible, if sensitive to lower price decks, and their share of supply was growing rapidly until the recent drop in prices. Production of marketed natural gas in the US in December 2008 was at its highest in the past 24 years.

Changing supply–demand conditions are probably the main reason developers of another regasification terminal in Canada, Kitimat LNG, announced plans instead to build a liquefaction plant targeting Asian markets. At the same time, a joint venture between Teekay Corp. and Merrill Lynch Commodities Inc. wants to convert an LNG carrier into a 500,000 tonnes/year floating liquefaction plant near Kitimat by 2012.

Decreasing global energy consumption and the consequent drop in oil and gas prices led to dramatic changes in Gazprom’s development and production plans. Gazprom officials have already discussed a production cut of as much as 7% in 2009. The company’s January 2009 production decreased 13.7% year–on–year, mostly due to reduced exports through Ukraine, but also because of reduced natural gas demand in Europe.

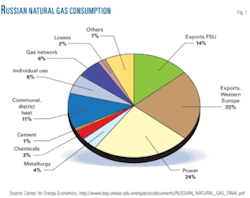

Domestic consumption, typically about 65% of Gazprom’s sales (see accompanying figure above), is also rapidly declining, following a dramatic drop in industrial production. Power generation, which accounts for roughly 40% of domestic gas consumption, slipped 7.3% year–to–year in January 2009. Export–oriented industries, the major natural gas industrial consumers, proved even more vulnerable to deteriorating market conditions. The chemical industry experienced a 74.1% dive between November 2008 and November 2007, while metallurgy was off 86.7%, wood processing 81.4%, and pulp and paper 85%.3

Gazprom’s storage is practically full due to continuous low demand in both domestic and international markets. The lack of storage capacity deprived the company of any production flexibility and caused production to decline further. Even some of the independents, which can only export through Gazprom, started reducing their production.

Reduced demand by both domestic and international customers, however, should be a short–term phenomenon, with demand picking up relatively quickly, albeit at a slower pace. In the long run, independents should provide a level of comfort to both Gazprom and its customers, including Europe.

Independent Russian companies increased production in 2008 by 8.9%, to 113.5 billion cu m/year. They are continuing to invest, albeit at reduced rates given current economic conditions. In the future, they may provide a hedge against the risk Central Asian supplies may move away from Gazprom, eastward to China, for example. Gazprom has long–term contracts with most domestic independent suppliers but had to renegotiate contracts with Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, and Kazakhstan multiple times.

Financial position

Lower natural gas prices will take a toll on Gazprom in 2009 and, due to the structure of export contracts, restrict its 2010 finances as well. The announced liberalization of domestic prices, however, will likely go on as planned, providing a counter to falling export revenues. Natural gas tariffs for nonresidential customers increased 25% in 2008 and a further 15% in 2009 (reduced from an initially planned 28% hike). Despite the price increase, domestic demand should not fall to levels sufficient to erase the tariff gains in Gazprom revenues.

It is also likely that lower demand will slow development of capital–intensive projects such as Bovanenkovskoye and Kharasavey fields in Yamal. These natural gas fields stand as the major resource to replace falling production at the mature Yamburg, Urengoy, and Zapolyarnoye fields.

Gazprom invested about $2 billion in Bovanenkovskoye and Kharasavey fields in 2008, in addition to another $1 billion in infrastructure in the Yamal peninsula. About a third of the investments were in non–Yamal exploration and production activities, and another third on transportation and storage facilities outside Yamal. Current Yamal investments remain at roughly $5.5 billion for the time being but will likely be reduced.

Gazprom’s total 2009 investment plans have already been reduced by 10%, to about $27 billion, two thirds of which is capital expenditures. The final effect of these new budget numbers on major projects remains unclear. Part of the 10% decrease in dollar terms can be explained by the large devaluation of the ruble in recent months. But at the same time, materials and services for infrastructure projects have become cheaper.

The combination of low energy prices and shrinking sales revenues, however, could greatly affect Gazprom over the next 2 years. With prices for Urals at $35–45/bbl, Gazprom will have to increase borrowing from the $2.5 billion budgeted for 2009 to continue its investment program. Company officials have already visited Asian and Middle Eastern financial centers seeking funds.

Gazprom’s reaction to increased excitement about Nabucco has been to emphasize South Stream and Nord Stream, but these are extremely capital intensive projects. Gazprom recently estimated South Stream’s cost as high as $32.5 billion, while North Stream would cost as much as $11.6 billion, including $2.6 billion in 2009. South Stream can be effective for the time being simply as a counter to Nabucco, but Nord Stream construction has started and needs continuous funding.

Gazprom may have no choice but to ask the Russian government for support. But the government’s ability to do so may be limited. The latest (Jan. 19, 2009) official budget forecast for 2009 stipulates an average Urals price of $41/bbl, an exchange rate of 35.1 rubles/$, and a 6–8% federal budget deficit in 2009 followed by 4–5% deficits in 2010 and 2011. These deficits would be covered by reserve funds, but would likely drain them by 2012.4

References

- “The Concept of Long–Term Socio–Economic Development of the Russian Federation,” Ministry for Economic Development of the Russian Federation, August 2008 (in Russian).

- “Natural Gas Demand and Supply, Long Term Outlook to 2030,” EuroGas, 2007.

- “The main parameters of socio–economic development for 2009,” Ministry for Economic Development and Trade of the Russian Federation, December 2008. Available at: http://www.economy.gov.ru/wps/wcm/myconnect/economylib/mert/welcome/economy/macroeconomy/administmanagementdirect/doc1229698624942.

- “Novii Kurs” (“New Deal”), Vedomosti, Jan. 20, 2009.

The authors

Dmitry Volkov ([email protected]) joined the CEE in October 2003. Volkov is involved in various research projects, including LNG and carbon sequestration value chains, as well as studies of FSU energy sector development and international energy data systems. He is an active member of the Association of International Petroleum Negotiators (AIPN). Volkov holds degrees from University of Houston (MBA, accounting and finance) and Moscow State University, Institute of Asian and African studies (BS, Arabic studies and history).

Gurcan Gulen ([email protected]) is a senior energy economist at the CEE. Gülen comanages a 5–year cooperative agreement with the USAID, focusing on capacity building in energy sectors of emerging economies in Africa. He also directs content development for the New Era in Oil, Gas & Power Value Creation, CEE’s international capacity building program. He served as an officer in both the Houston and national chapters of the International Association for Energy Economics. He received a PhD in economics from Boston College and a BA in economics from Bosphorus University, Istanbul.

Michelle Foss ([email protected]) is chief energy economist and head of the CEE. She directs and conducts research on energy fuels, markets, infrastructure, and associated investment frameworks; advises US and international energy companies; publishes and speaks widely on energy issues; and provides public commentary and government testimonies. Previously, she was a director of research at the investment bank Simmons & Co.; director of research at Rice Center, an urban regional economics, energy, and transportation research group; and was engaged in Denver–based energy and environmental research and consulting. Foss is a member of the Council on Foreign Relations, AIPN, USAEE/IAEE, Women’s Energy Network, and a partner in Harvest Gas Management, a Texas–based exploration company. Foss holds a PhD in political science from the University of Houston, an MS in economics from the Colorado School of Mines, and a BS in biology, with a geology minor, from the University of Louisiana–Lafayette.

Ruzanna Makaryan ([email protected]) is a senior energy analyst at CEE–UT. She has been with the Center since 2002. She previously worked in Turkmenistan with PA Consulting Group, implementing USAID–sponsored technical assistance programs for Turkmen government agencies in the oil and gas sector. Ms. Makaryan holds an MBA from the University of Houston’s Bauer School of Business and a BA in linguistics from Turkmen State University. She is a member of the Project Management Institute, World Affairs Council of Houston, and American Institute of Chemical Engineers.