Changing a pipeline company’s name following a merger or acquisition requires a comprehensive, unified approach. Failure to properly organize and execute the name-change process can lead to unnecessary delays, regulatory complications, and the additional costs associated with both. This article describes one such process, demonstrating the benefits accrued from using a systemic approach.

Background

Several generations of acquisition, divestiture, and other company transitions may be included in a pipeline’s genealogy. Completing a simple name change of a company’s assets can quickly evolve into a complicated maze of uncertainties related to who owns what, who operates what, and how everything is regulated by various government agencies.

In the case examined for this article, Company A, Company B, and Company C merged with parent Company F several years earlier, placing most of A’s holdings under Company D and all of B’s holdings under Company E. Company C retained its name.

Company A initially operated the pipeline facilities; then its employees made the transition to become employees of Company F. This period of transition left behind remnants of the past companies’ names—including a hybrid of the two names—in assets, manuals, permits, registrations, etc.

This project sought to change the name of the remnant assets of Company A to a newly formed company, Company G. “Name change” applied to a legal name change for a specific company’s assets and to regulated operational activities. Indentifying associated assets of sister Companies C, D, and E facilitated the process.

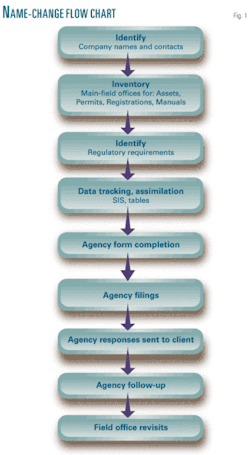

Company F, which was the new operator of the assets of Companies C, D, E, and G also had to be identified in applicable permits, registrations, and internal documents. Some permits and plans required correction of the owner and operator involved due to the multiple transitions. Fig. 1 shows the acquisition, change of operators, and name change. Fig. 2 shows the steps taken to complete the name-change project.

Company personnel in the example outlined by this article included specialists, team leaders, field team leaders, and operators, all of whom provided information important to the process’s success.

Having identified the players in the acquisition, Company A’s remaining assets now had to be determined. Prepared inventories facilitated the correct cross-referencing of owner-operator for permits, registrations, plans, etc. But a complete inventory of these items may not be readily obtained as part of an acquisition because of an incomplete transfer of documents. Cross-referencing permits with the files of the appropriate agency can provide a better understanding of the company’s history.

Assets

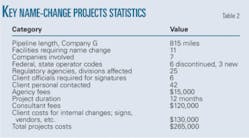

About 815 miles of pipeline from 10 hazardous liquid and gas systems transferred as remnants from Company A to Company G. Pipe diameters were mainly 6-8 in., although sections of larger diameter pipe were also included in the inventory.

The asset study also identified 19 separate facilities, including gas separation-processing-dehydration, barge loading, underground gas storage, and pump, compressor, and booster stations. Operators had taken four of the identified facilities permanently out of service and permanently leased another to an outside company. Several other companies also held 33 of the meter stations.

Methodology

A spreadsheet called the stoplight information spreadsheet (SIS) assisted in identifying and tracking acquired information. This included a comprehensive list of all potential applicable regulatory requirements, agencies, and regulated changes and a stoplight color code to track project progress. SIS identified about 200 potential regulatory requirements for this company name-change process involving as many as six federal and 16 state agencies. SIS also identified 14 company employees, contractors, and vendors to manage selected tasks in the name-change process.

Three categories of contacts provided data over the course of the name-change project:

- Company personnel.

- Regulatory agencies.

- Company contractors.

A list provided by the client initially identified key company personnel. A list of permit information provided by the client initially identified applicable regulatory agencies, permits, and plans. Interviews with company personnel identified company contractors. Communicating with contractors helped determine what tasks they performed and how they could best be informed of any name change procedures related to their tasks. Each of these lists expanded as additional information was gathered.

Table 1 provides an abridged sample of the SIS spreadsheet.

Inventorying

Inventory of acquired assets was a necessary early step in the name-change project. Participants found the list of assets on hand to be out of date and correct information not easily attainable. Visiting the client’s main office, field offices, and key operational facilities and interviewing employees eventually yielded accurate inventory information.

Field-site visits proved invaluable in identifying operations and facilities abandoned due to process change and natural gas availability. Such assets as wells and septic tanks, as well as field vehicles such as trailers, boats, and ATVs, were included in the inventory’s scope. Some vehicle registration information was lost during Hurricane Katrina, requiring duplicate titles be requested from the motor vehicles office before filing the name change forms.

Identification of additional company names during the inventory process made attributing ownership and operator names to certain assets confusing. The perator was not certain of same-asset ownership, especially information pertaining to acquisition and divestiture to sister companies. Names of past companies and hybrid names existed in manuals, permits, registrations, etc., all of which had to be identified and corrected.

Agency forms

Agency form completion followed the inventory process as the second most important task to be addressed during the name change. The client was assisted in completing operator-name change regulatory agency forms for air and water permits, coastal use-Army Corps of Engineers permits, operator identification numbers, injection-drill permits, vehicle registrations, and drip points registrations.

Identifying and confirming responsible company officials who would provide signatures before form completion expedited the form-signing process. The consultant paid form fees and was reimbursed by the client, avoiding delays and any bottlenecking of documents.

Internal documents

The client or its vendors completed name changes to agency forms electronically filed by the client, and to client documents such as manuals and plans. In some cases it was more efficient for the client to electronically file the changes themselves through their secured web site including annual reporting to the US Department of Transportation’s Office of Pipeline Safety. In other cases, changes to manuals and plans were completed by the client or their vendor, including owner-operator name changes to integrity management plans and spill prevention, control, and countermeasure (SPCC) plans.

Report preparation

Hard copies of the name-change report given to the client for distribution to its legal department and other appropriate departments provided guidance and acted as a tracking tool before and during the formal name change process. The name-change report included a record of the asset inventory and any letters to the agencies with completed forms. Color coding name-change requirements by sister company helped identify specific name-change requirements, since seven company names were involved.

Revisiting the field offices after completing the name-change process helps ensure all documents affected by the change have been updated.

Discussion

RCP used several procedures smoothly to move the remaining assets of Company A to Company G and avoid processing delays once the go ahead for the name change was given. A turnkey approach included obtaining a signature list for documents requiring signatures and paying form fees directly to expedite the process. Extensive interviews with experienced field personnel accessed accurate company background information.

Discussion with well-informed individuals, including land people, and use of geographic information systems helped resolve any unclear items. Reporting potential regulatory violations to the client before submitting name change documentation to the various agencies avoided processing delays.

The parent company was not always certain of asset ownership, and different opinions were discovered within the company. In addition, monies allocated to field offices for name change purposes were sometimes diverted to other projects, escalating the actual costs of the name change project. Several facilities determined to be permanently out of service were still included in active permits, resulting in additional liability and extra expense from permitting fees and sampling fees.

The client lacked a comprehensive and accurately identified inventory of permits, registrations, and plans due to an incomplete transfer of information. In-house copies of permits often retained the names of former owners and operators. Some permits may only be renewed every 5 years and a name change may have occurred within this period and therefore would not be readily apparent on copies of in-house permits. These circumstances were corrected through contact with regulatory agencies when copies of all in-house permits were cross-referenced and verified to determine the accuracy of existing permit status, owner, and operator.

Table 2 shows some of this name-change project’s key statistics. Any efficiency savings stemming from having used an integrated approach to the project exceeding the $120,000 included for consultant costs can been seen as a net gain.

The authors

Kenneth T. Palmer, PhD ([email protected]) is a senior compliance consultant at RCP Inc., Houston. He has over 30 years’ experience in the oil and gas, government, and chemical industries. He holds a PhD from the University of Missouri (1992).

Bill Byrd, PE ([email protected]) is president of RCP Inc., an engineering and regulatory consulting firm headquartered in Houston. He has 29 years’ experience in the oil and gas industry and is actively involved in several industry committees. He has a BS and MS in mechanical engineering from the Georgia Institute of Technology (1981, 1982).