China’s refining expansions to reshape global oil trade

Global oil refining capacity is set to expand by more than 10 million b/d over the next 7 years, with new refinery projects in Asia accounting for roughly 40% of this total.1 New Asian refining projects include Indian and SE Asian export refineries, but are dominated by expansions and greenfield projects in China.

Driven by rapid oil product demand growth and a desire to slash feedstock costs, China’s oil refining sector is expanding rapidly and augmenting its ability to refine a wider variety of crude oils. This will have geopolitical implications as China becomes able to use more crude from a wider range of suppliers. China’s growing ability to refine lower quality sour and acidic crudes may also reduce large price differentials between these and higher quality light, sweet crudes.

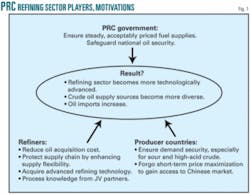

Additionally, if Beijing continues to control Chinese oil product prices and restrict exports of refined products from China, Chinese refiners may face increasing pressure to invest in refining projects abroad as a way of escaping price controls and enhancing shareholder returns. PetroChina and other major Chinese oil producers and refiners are now partially owned by private investors, who likely will emphasize profit before politics. Fig. 1 shows key motivations for the participants in China’s refining sector modernization.

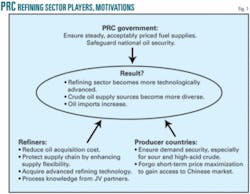

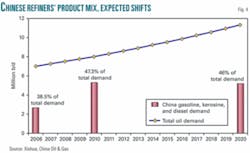

China’s rising motor vehicle ownership, plans to double the size of its road network, and its domestic firms’ huge fixed investments in steel, petrochemicals, and other energy-intensive basic industries could drive oil imports to 7 million b/d of crude oil by 2020double today’s imports.2 Fig. 2 shows an approximation of China’s current oil demand structure based on 2005 data.

China’s refining sector

China currently has more than 6.3 million b/d of domestic refining capacity and imports products such as fuel oil to meet its total demand of 7.4 million b/d of crude and products. Because the Chinese refining industry was built around light, sweet crude supplies from Daqing and other Chinese fields, it lags international refiners’ ability to process lower quality, high-sulfur and high-acidic crudes, which raises feedstock costs and narrows the list of potential crude suppliers. Some Chinese sources estimate that crude oil acquisition can account for 90% of a refinery’s operating cost. Thus, being able to process a wider variety of crudes can have a positive impact on a refiner’s profitability.

China National Petroleum Corp. (CNPC) and Sinopec are China’s two chief refiners, but the Chinese refining industry counts more than 120 individual refining enterprises. One byproduct of the large number of small refiners is that Chinese refineries are much smaller than the international average, processing 52,000 b/d of crude oil, compared with the international average throughput of 114,400 b/d. The Chinese refining sector’s relative lack of consolidation hurts efficiency, as indicated by its high energy consumption per ton of oil refined compared with the rest of the world.

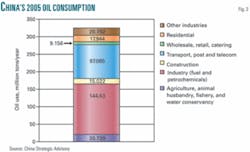

Thus, consolidation and overall refining capacity expansion will be major future trends. The National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), China’s main energy planner, forecasts that China will add 1.8 million b/d of refining capacity by 2010 while shuttering 400,000 b/d of old capacity at small, uncompetitive plants.3 NDRC notes that, as part of the country’s 11th 5-Year Plan, Chinese firms are slated to build at least eight 200,000 b/d refineries. Much of the new capacity will be intended to refine heavy, sour, and high-acid crude oils, which are more plentiful and often cheaper than the light, sweet crudes existing refineries handle (Fig. 3).

NDRC also notes that Chinese refiners’ product outputs do not match the country’s demand needs, triggering demand for product imports to offset this imbalance (Fig. 4). Product imbalances are particularly acute with respect to gas oil and naptha, which are key feedstocks for ethylene and other petrochemicals. These factors will create business opportunities for engineering and construction firms, technology suppliers, and international producers and refiners who are nimble and have high risk appetites.

Changing crude slates

Chinese analysts state that their country’s oil refining sector needs reforms, including:

- Increased refinery flexibility to reduce feedstock cost.

- Enhanced capacity for deep processing of heavy oils.

- Increased process efficiency.4

- Tighter integration between refineries, petrochemical producers, oil ports, pipelines, and commercial and strategic oil storage.

Chinese refining capacity will expand overall by 3.3 million b/d during 2006-11. Roughly 2.55 million b/d of this will come from building new refineries, while the remaining 651,000 b/d will consist of refinery expansions and additions of hydrocrackers to enable refineries to maximize high-value product outputs and hydrotreaters to allow them to process more sour crude.

A key trend is the addition of new refining capacity geared heavily toward heavy, sour, and high-acid crude. Much of China’s original refining capacity was built to handle the output of its workhorse Daqing and Shengli fields, which produce light, sweet crude similar to Indonesia’s benchmark Minas grade. As a result, China’s ability to work with lower quality sour and high-acid crudes has been limited.

In 2006, only 15% of China’s refining capacity could handle sour crude oil of the kind that comes from Iran, Saudi Arabia, and other core suppliers. To put this in perspective, 82% of US refiners can handle sour crude oil, with a lower percentage able to process a large proportion of high-acid crudes.5

Several factors are motivating Chinese refiners to expand their ability to handle sour and high-acid crudes. The primary driver is economic. The price of crude oil is a major operating cost, and if a refiner can lower his feedstock costs, all other things being equal, his profit margins will rise. The discounts on lower quality crude oils can be substantial. In July 2007, for example, high-acid Doba blend from Chad was selling at a discount of $17/bbl relative to Dated Brent, a key international crude pricing benchmark. Lowering crude feedstock price by incorporating such oils can have major bottom line benefits.

In 2006, Sinopec ran 200,000 b/d of high total acid number (TAN) crude.6 Sinopec executives have claimed that experimenting with high-TAN Doba blend from Chad at its new Guangzhou refinery boosted refining profitability. US refiner Sunoco had similar results in 2005 from running heavily discounted Doba. In 2004, Sunoco refineries ran only light, sweet crude, causing average crude costs to exceed the West Texas Intermediate (WTI) benchmark by an average of $1.14/bbl. In 2005, using high acid crude lowered the company’s average crude cost to 15¢/bbl lower than WTI, which substantially improved refining margins.7

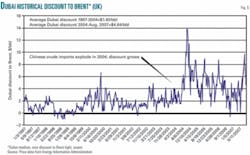

Middle East sour crudes also often sell at a large discount relative to light, sweet oils, which are easier to refine and often have higher gasoline and diesel yields. Figs. 5 and 6 show historical price differentials between Dubai and Saudi Arab Medium, both of which are heavy and sour, and Brent and Bonny, both of which are light and sweet. The differentials widened sharply in 2003-04 as Chinese demand for light, sweet crude shot up. During this time, China accounted for a good portion of global incremental oil demand growth.

So refiners have a strong economic incentive to increase imports of sour and high acid crudes. Refining sour crude typically requires refineries to install hydrotreaters and other desulfurization equipment. Refiners have three primary options for utilizing high acid crudes. First, those having large throughputs, such as Zhenhai, Guangzhou in China, and Reliance in India, can run high acid crude through “normal” refineries by blending it with other crudes. This allows refiners to capture economic benefits without retooling facilities.

In addition, certain crude blends complement each other when blended. Angola’s acidic Kuito, for example, blends well with sour Saudi Arab Light because the Saudi dilutes the Kuito’s acidity, while the sweet Kuito reduces the product stream’s sulfur content and maximizes valuable middle distillate yields.8 Refiners can also blend sodium or potassium hydroxide into the crude stream to reduce acidity. Finally, new refineries dedicated to a high-acid feedstock such as PetroChina’s Guangxi refinery, which uses the Sudanese Dar Blend, are built from corrosion resistant steels.

New supply geopolitics

The global oil supply is gradually getting heavier and more sour. Being able to handle crudes from a wide range of suppliers will give Chinese refiners greater strategic and economic flexibility.

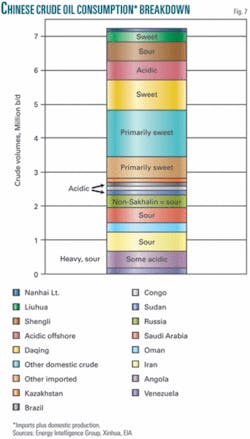

As Fig. 7 shows, China is drawing its crude oil supply from an increasingly diverse array of sources. Many are heavy, sour, or acidic. A large proportion of Chinese offshore production from Penglai and other fields is acidic15% of total domestic production while African crude streams also are increasingly acidic. China takes roughly one third of its crude imports from Africa as it works to diversify away from the Middle East.

China’s primary Latin American oil suppliers, Venezuela and Brazil, are also “complex” crude suppliers. Brazilian offshore production is predominantly acidic, while Venezuelan oil is often simultaneously heavy, sour, and acidic. Venezuela wants to boost its crude exports to China, but the transportation economics remain uncertain. However, a study by Roy Nersesian of Columbia University and Poten & Partners notes that the economics of using very large crude carriers that offloaded in the US Gulf of Mexico to carry Venezuelan crude on their “backhaul” voyage compares very favorably to the costs per barrel of carrying Venezuelan crude to US Gulf refineries on smaller Aframax tankers, as done in the current trade.9 Thus, if China continues to expand its heavy and sour refining capacity, it would become economically feasible to greatly expand the Sino-Venezuelan oil trade, should both sides agree to do so.

Finally, Middle Eastern supplies are likely to occupy an increasing percentage of the global oil supply in coming years, and these barrels are almost unanimously sour and relatively heavy. As Chinese refiners enhance their ability to deal with high-acid, sour, and heavy oils, it is likely that China’s commercial and geopolitical oil relationships with complex crude producers in Africa and the Middle East, as well as Venezuela and possibly Canada, will deepen.

Product price reform

Domestic oil product pricing reforms will have a major influence on Chinese refining development. Chinese refiners are trapped in a tough situation, as they must pay international prices for imported crude oil, but must sell diesel, gasoline, and other products at government controlled prices within China.

China’s largest refiner, Sinopec, has a small crude oil production of its own relative to its refining capacity and is thus particularly exposed to high international crude prices, causing it to lose an average of $1.09/bbl of crude refined in 2006. In contrast, US Gulf Coast refiners enjoyed margins of $10-16/bbl during that time (the long term global average is closer to $5/bbl).

Chinese refiners are torn between several critical demands, each of which is tough to address in isolation, much less as a whole. First, they face economic demands, as they need to make money and to some extent serve shareholder interests. Second, there are political demands since they are national providers of motor fuels. If Chinese refiners cannot meet the bulk of product demand, international oil companies will balk at selling refined products at a loss to China and Chinese product importers will have to bear the cost difference. Third, Chinese refiners are burdened by the social demand of keeping farmers, fisherman, car owners, truckers, shippers, and other constituencies satisfied. Indeed, one Chinese energy analyst characterizes the situation as: “If you wish to discuss economics, you must also discuss politics.”

Finally, Chinese refiners must deal with an increasingly competitive market in which they face both domestic competition and foreign refiners as China opens its internal oil and products markets as stipulated by the World Trade Organization. China’s oil wholesale market was opened to domestic and foreign investors in January 2007.

There are catches, however, as oil wholesale licenses are not useful unless accompanied by oil import and export licenses, which typically are controlled by CNPC, Sinopec, and affiliated operators and are tough to acquire. Companies wishing to engage in the oil wholesale business in China must also maintain at least 1.25 million bbl of storage capacity, posing another barrier to entry.10

Some Chinese analysts fear product market liberalization because they believe stronger foreign firms might displace Chinese companies and that foreign ownership might rise in the strategic refining sector. They also fear that it would lead to increased product imports and higher foreign exchange expenditures because products are often more expensive per barrel than crude oil. Chinese oil product markets are evolving despite continued price controls. Private firms are now getting licenses for product wholesalingan area that was formerly the exclusive domain of CNPC and Sinopec. In the first 6 months of 2007, China’s net refined product imports averaged roughly 450,000 b/d, largely from Singapore.11

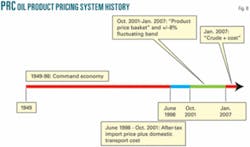

That said, the Chinese government is gradually reforming its price controls in ways that are moving Chinese refined product prices closer to international price parity. Prior to 1998, NDRC simply capped prices. In June 1998, NDRC began using after-tax import prices plus domestic transport cost as the basis for fixing benchmark retail prices for oil products. Sinopec and CNPC then used this baseline price to reach a final retail price, which was allowed to fluctuate within a very narrow range. Beginning in October 2001, NDRC adopted a system whereby domestic refined product prices were based on a “price basket” of New York, Rotterdam, and Singapore product prices and allowed to fluctuate within a ± 8% price range.

NDRC’s newest product pricing method, adopted in late January 2007 uses a “cost plus” system to determine refined product prices (Fig. 8). Under this scheme, Brent, Dubai, and Minas crude oil prices serve as benchmarks, upon which NDRC adds a fixed profit for refiners. The new method’s key benefit is that it adjusts domestic product prices more quickly in response to international crude price fluctuations.

The prior regimes all caused Chinese refined product prices to seriously lag international crude prices, so that during crude price spikes, Chinese refiners paid full international prices for crude but could then not recover their cost with domestic product sales. This was a serious disincentive to refining sector development and is likely a key reason that NDRC adopted the new “cost plus” system despite its short-term disadvantages from the consumer’s perspective.

It is tough to say when Chinese oil product prices might near parity with international prices. One recent barrier to further price liberalization is that recent fears of inflation have driven NDRC to refuse any further fuel price increases for the time being.

That said, as Chinese oil demand grows, the government’s insistence on subsidizing oil product prices could become increasingly unsustainable, causing powerful economic forces to drive Chinese product price liberalization, although perhaps not to full international parity in the near-term.

First, Chinese refiners may shift some operations overseas to escape price controls and enhance shareholder returns. This could take the form of joint investment in overseas projects, which would reduce capital available for projects desired by state regulators in China. Or, Chinese refiners could build wholly owned plants abroad, which would have an even more pronounced impact on refining project capital availability in China. Such moves have not yet occurred on a large scale, but it will be interesting to see how Beijing reacts if refiners look to shift operations outside of China. One possibility is that the government might force them to import product equal to that which they would have produced, which would erase most economic gains from investing in overseas refining projects.

Second, the Chinese government will face spiraling subsidy cost increases. In 2005, with oil prices lower than today’s and Chinese refiners processing roughly 5.72 million b/d, the government had to reimburse refiners 104 yuan/bbl of oil processed, at a total cost of 30 billion yuan ($3.7 billion).14 By 2012, China likely will be refining and consuming as much as 9 million b/d of oil. This means that conservatively assuming a need for 100 yuan/bbl in refining subsidies, the Chinese government would be paying the equivalent of roughly 330 billion yuan in subsidies (about $43 billion at current exchange rates).

Foreigner squeeze

Will Chinese refining growth create commercial opportunities for foreigners? Chinese companies are learning fast and are willing to proceed alone if international partners don’t bring enough to the table or move too slowly. Royal Dutch Shell was originally slated to partner with China National Offshore Oil Co. (CNOOC) on the 240,000 b/d Huizhou refinery but pulled out after 3 years of talks, leaving CNOOC to forge ahead by itself. Similarly, although Sinopec is keeping foreign partners ExxonMobil and Saudi Aramco for its 240,000 b/d Fujian project planned for 2009, plans for a follow-on JV in Guangzhou seem to be dead, and Sinopec looks ready to proceed alone.12

The trend of foreign firms being “squeezed out” of China’s refining-petrochemical industry is being hastened by Chinese companies’ rapidly growing construction and engineering expertise. Sinopec Engineering alone has completed more than 450 refining and petrochemical process units over the past 30 years.13 While this figure lags the track record of foreign engineering and construction firms such as Foster-Wheeler and KBR, it shows the considerable refining experience and expertise rapidly becoming resident in China.

Western specialty firms still have niche markets for certain heavy lift capabilities, providing catalysts and supplying other advanced process technologies and equipment. Yet the big-ticket plant construction market is closing fast to outside firms. One Beijing-based refining and petrochemicals consultant notes that Chinese firms are building more than 80% of the ethylene steam cracker capacity currently under construction. By contrast, only 50% of the capacity that came online during 2004-06 was Chinese built, and projects included Western companies such as Shell, BASF, and BP as partners.14

This indicates that in the future, foreign firms’ value added to potential Chinese refining and petchem partners will be determined primarily by their ability to provide either feedstock supply or access to downstream markets overseas. Since most Chinese projects for the next 5 years are aimed at the domestic market, supply-rich national oil companies will have a big advantage over private international oil companies in securing future refinery-petrochemical investment deals in China. Chinese refineries’ moves to partner with Aramco and Kuwait Petroleum Corp. also help protect the national oil supply because a supplier is unlikely to cut supplies to refineries in which it holds investment stakes and which provide gateways to a huge oil products market.

A global powerhouse

The Chinese refining sector is unique because, while it is already the world’s second largest after the US, it still has substantial upside growth potential. Even a conservative demand growth of 5%/year means that Chinese oil demand will expand by more than 300,000 b/d, or the equivalent of a large new refinery each year for some time to come. China also is the centerpiece of the refining and petrochemical industry’s eastward shift, which is driven by strong demand, national desire for self-sufficiency, and more permissive industrial policies than those of Western countries.

China’s refining industry growth will have several key commercial implications. First, as Chinese demand for sour crude rises as an overall proportion of crude consumption, growing Chinese pull on sour crude supplies may help reduce the current price differentials between sweet and sour oils. Higher Chinese sour crude processing capacity also will increase Chinese refiners’ crude acquisition options and could shift trade patterns for Middle East and Venezuelan sour crudes.

Increased Chinese sour crude purchases of about 3 million b/d by 2012 could also provide major support for the new Dubai and Oman sour crude contracts. Finally, products surging onto the market after 2010 from new Chinese and Indian refineries could greatly lower regional refining margins. Depending on refiners’ ability to export products, margins could be affected as far away as the US West Coast and Gulf of Mexico markets.

In short, China is positioned to lead the emergence of a new Eastern center of gravity in the world oil refining and petrochemical industries. Just as strong and sustained Chinese oil demand growth is reshaping the global upstream and oil shipping businesses, so too will it affect the refining and petrochemical businesses.

References

- John van Schaik, “Global Refining Capacity Set to Expand,” International Oil Daily, Feb. 9, 2007, Lexis-Nexis (http://web.lexis-nexis.com).

- The US currently imports 10-12 million b/d of oil and products.

- Wang Yusheng, “Panorama of China’s Oil Refining Industry in 2005,” China Oil & Gas No. 1, 2006, p. 51.

- “Refinery Netbacks: Gold Coast Margins,” Oil Market Intelligence, May 15, 2006, Lexis-Nexis, (http://web.lexis-nexis.com).

- Petroleum Intelligence Weekly, accessed July 17, 2007.

- “Sunoco runs more high-acid crude, posts record profit,” Oil Daily, Aug. 4, 2005, Lexis-Nexis. (http://web.lexis-nexis.com).

- “Refining Characteristics: Kuito,” Chevron, (http://crudemarketing.chevron.com/characteristics.asp?kuito).

- Roy Nersesian, “The economics of shipping Venezuelan crude to China,” The Oil and Gas Review, Business Briefing: Exploration and Production, 2005, Issue 2, (http://www.business-briefings.com/pdf/1736/nersesian_lr.pdf).

- “New Guidelines for Foreign Firms,” China Energy Weekly, Mar. 28, 2007.

- “China consumes record amount of crude, refined oil in first half of 2007,” Xinhua, July 24, 2007, obtained through Open Source Center.

- “China’s oil refining industry posts loss of 30 billion yuan in 2005,” People’s Daily Online, Feb. 14, 2006, (http://english.peopledaily.com.cn/200602/14/eng20060214_242611.html).

- “Chinese refining still tough nut for foreigners,” Petroleum Intelligence Weekly, Mar. 19, 2007, Lexis-Nexis, (http://web.lexis-nexis.com).

- “Bechtel-Sinopec Engineering Inc.-Foster Wheeler consortium awarded China petrochemical contract, Mar. 15, 2001, (http://www.bechtel.com/newsarticles/119.asp).

- John Richardson, “Construction Crisis? What Crisis? China Leads the Way,” John Richardson’s Asian Chemical Connections, Aug. 14, 2007, (http://www.icis.com/blogs/asian-chemical-connections/2007/08/construction-crisis-what-crisi.html#more).

The author

Gabriel Collins ([email protected]) is a research fellow in the US Naval War College’s China Maritime Studies Institute, Newport, RI. His primary research areas are Chinese and Russian energy policy, maritime energy security, Chinese shipbuilding, and Chinese naval modernization. He is a member of the International Association for Energy Economics. Collins is an honors graduate of Princeton University (2005) and is proficient in Mandarin Chinese and Russian.