Aboveground constraints may limit Mexico’s oil production

The irreversible decline of Mexico’s Cantarell field has been the subject of steady discussion in the industry. The broad consensus is that Mexican oil production levels are at serious risk, with concomitant implications for international oil markets. For the most part, however, analysts have focused on what a drop-off would mean for the US, 16% of the crude imports of which come from its southern neighbor.

But what does Cantarell’s decline means for Mexico itself, currently the world’s sixth largest oil producer? Consider these issues:

The socioeconomic consequences of a decrease in oil production, then, would be profound for Mexico, leaving the country with what one analyst called a “nightmarish budget crisis.”

New direction needed

As the erosion of Cantarell’s output proceeds after several years of enhancement from nitrogen injection, pressure intensifies on Mexico’s oil industry to offset the decline. Thus, the search is on to find and develop new fields that not only replace losses from Cantarell but ultimately allow Mexican production rebound. It is increasingly clear, however, that a difficult—and different—path lies ahead.

Two leading experts on Mexico’s oil situation have stressed that “business as usual” will not enable the country to meet its oil production goals, and they suggested actions more likely to succeed:

- Pemex must be permitted to develop strategic alliances with technologically sophisticated international oil companies, says George Baker, publisher of Mexico Energy Intelligence.

- Pemex must pay more attention to exploration to balance its emphasis on production if the country hopes to meet its long-term goals, insists David Shields, an independent oil analyst and author of several books on Pemex.

- The company also needs to systematically refurbish and expand its facilities along the entire energy supply chain, Shields says.

These changes will require major adaptation by the country’s leaders. The 2008 energy reform bill, which passed through Congress in October, does not offer the sweeping changes the oil industry needs.

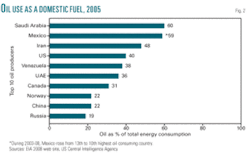

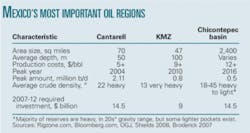

Pemex officials express confidence that two other oil systems will be able to compensate for Cantarell’s terminal decline. The onshore Chicontepec basin and offshore Ku Maloob Zaap (KMZ) together are estimated to hold 53% of Mexico’s reserves and 72% of non-Cantarell reserves.1

While these regions will require extensive capital expenditures, sophisticated technology, and time to develop, they appear to be Mexico’s greatest opportunities over the next decade to compensate for Cantarell’s decline.

Unfortunately, there is a growing likelihood that even if the key technical challenges are tractable, aboveground issues in Mexico will constrain production and limit exports. Cambridge Energy Research Associates (CERA) contends that the greatest threats to global production increases are not belowground but rather from the human conditions of politics, economics, regulation, and a hesitancy to proceed.

Resource nationalism

In 1938, Mexico became the first major producer to expel international oil companies (IOCs)—mostly American and British—and created Pemex. This event remains a symbol of sovereignty and a source of national pride.

Numerous politicians have played on this emotion and railed against any “theft of the oil industry” by outsiders. Mexico’s leading leftist political figure, Andres Obrador, has steadfastly opposed private investment in the oil sector. “The country’s oil belongs to the people, even the most humble. We must defend this historic conquest,” he said.2

Mexico’s oil industry, therefore, has little opportunity to partner with foreign companies to improve production, despite the expertise and technology such firms could provide. The Mexican people distrust IOCs, especially those from the US, and proposals for private investment generate mass protests throughout the country. A recent poll showed that 62% of the population opposes partnering with IOCs.3

However, the administration of President Felipe Calderon, a former energy minister, realizes that Mexico must seek help in developing its energy resources. In a February interview, Energy Minister Georgina Kessel said. “We are looking for (Pemex) to have the flexibility to form associations like all the companies in the world.”4 Calderon was even more explicit in a televised national address. “We must act now. Time and our oil are running out,” he said.5

But Calderon’s April initiative, pushing for outside investment in deepwater oil exploration and production (E&P), remains unpopular. “We are in complete disagreement with the [Calderon] government,” said Manlio Beltrones, a senator from the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), in a radio interview.6

Ordinary Mexicans are understandably skeptical when private investors access state enterprises. Mexican businessman Carlos Slim was ranked as the richest man in the world in 2007, mostly by making billions from the privatization of Mexico’s national telephone company, Telmex.

Aging infrastructure

Pemex’s financial troubles—exemplified by a staggering increase in debt to more than $110 billion in 2008 from $43 billion in 2000—have led to a patchwork oil infrastructure.7 8

The company lacks funds to modernize because Pemex pays such a high percentage of its revenues to the government. In 2006, for example, of $97 billion in Pemex sales, $79 billion (81%) went to federal coffers.9 As the government’s need for revenue escalates, funds to improve energy infrastructure decline. In 1997, Pemex had a budget of $2.7 billion for maintenance. In 2007, the budget was only $1 billion.10

A deteriorating pipeline system highlights Mexico’s infrastructure problems. Over the past decade, maintenance expenditures have been only one third of what is required, and more than half of the pipelines are operating beyond their 30-year lifespan.11 In an effort to maintain production, equipment is pushed to the limit, and ruptures regularly occur from excessive pressure. Pemex has consistently been forced to close pipelines because of a lack of maintenance, and it now needs over $3 billion for urgent pipeline repairs.

Recognizing these problems, Calderon has outlined a “National Infrastructure Program,” which includes investments of $75 billion in E&P and $27 billion in refining by 2012.8 Unfortunately, the urgency of maintaining the production system is the squeaky wheel that demands the grease. Over 80% of Pemex’s E&P budget is funneled into production rather than exploration (OGJ Online, Apr. 22, 2008).

Even according to relatively optimistic Pemex data, proved reserves have fallen 41% since 2000 to about 14.7 billion bbl.12 The US Energy Information Administration (EIA) indicates reserves have declined 75% since 1997 and now stand at 12.4 billion bbl. Shields’s March 2008 report for the University of California at Berkeley presents an even more cautious view, estimating Mexican reserves at 11.8 billion bbl.”8

Burgeoning demand

Mexico’s population, like that of many other energy-producing nations, is growing rapidly and consuming more energy, reducing exports.

Its population will increase to 140 million in 2030 from 109 million in 2008—an increase of over 25% in less than a generation.13

Economic growth is changing the face of Mexico. The gross domestic product will increase to $2.9 trillion in 2030 from about $1.4 trillion in 2007—an annual growth of 3.3%.13 This increase is the foundation of the rise of an energy-consuming middle class.

Automobile sales are up, and there is firm evidence that “gas guzzlers” from the US are finding their way to Mexico, raising fuel consumption.14 More importantly, forecasted growth in the number of vehicles in the next 20 years is staggering. J. Dargay, D. Gately, and M. Sommer, in a 2007 report, projected that Mexico’s vehicle fleet will increase to 66 million in 2030 from 17 million in 2002, an astounding quadrupling of vehicles in less than 3 decades.15 The group’s study found that the average annual growth rate for the number of vehicles in Mexico is nearly double that of the US and Canada combined.

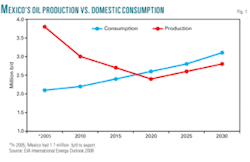

This energy demand growth has huge implications. EIA, in its International Energy Outlook 2008, projected that during 2005-20 Mexico’s oil consumption will increase by about 24%. Mexico will need 2.6 million b/d of oil in 2020—about 500,000 b/d more than in 2005. Mexico’s oil production, however, will have fallen to 2.4 million b/d from 3.8 million b/d during the same time. By 2020, Mexico’s oil consumption will have outstripped production by 200,000 b/d (Fig. 1).

By 2030, Mexico’s oil consumption will have increased from today’s by 48%. By then, Mexico will need 300,000 b/d more than it can produce. Interestingly, EIA is forecasting that Mexico’s oil production will increase to 2.8 million b/d in 2030 from 2.4 million b/d in 2020. It remains unclear what will ignite the 2020’s resurgence because EIA recognized that Cantarell is declining at 14%/year, and Pemex officials have admitted that KMZ and the Chicontepec basin will peak in 2010 and 2016, respectively (OGJ Online, Feb. 25, 2008).

Even if EIA’s optimistic forecast is correct, Mexico would still need to import 300,000 b/d to satisfy domestic consumption by 2030. But the country might need even more. What would make oil production increase 17% in 2020-30? Where will this oil come from?

Mexico’s shift—from US oil supplier to its competitor for oil imports—could happen very quickly.

In addition, burgeoning transportation demand has led to a drastic rise in gasoline imports since 2000. Mexico now imports about 40% of its gasoline.16 This growth is expected to increase by 58%—to a total of 489,000 b/d by 2015 (OGJ Online, Apr. 22, 2008). This demand is driven by the rising middle class, an increasing percentage of young people, and rapid urbanization that was not adequately planned.

Gasoline is wasted in the standstill traffic jams that are part of everyday life in the country’s large cities. Further, the current pipeline-storage systems are insufficient to handle increasing gasoline imports, and Mexico faces shortages. Virtually all gasoline imports come through the Atlantic port of Tuxpan, where facilities are outdated and capacity is constrained. Mexico’s northern states often face gasoline shortages.

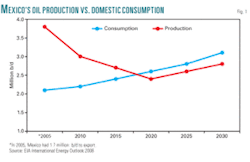

As Fig. 2 demonstrates, Mexico is more reliant on oil as an energy source than most major producers. Accordingly, socioeconomic dislocations from inadequate supply colliding with increasing demand will be severe.

Oil exports are at immediate risk. In fact, Mexico’s waning ability to export oil is already apparent. According to Pemex’s official June “Monthly Petroleum Statistics,” total exports fell to 1.7 million b/d in 2007 from about 1.8 million b/d in 2006—a 6% reduction and a decline that is expected to accelerate. In May, Pemex’s exports to the US dropped to 1.2 million b/d, a 21% decrease in just 1 year.17

Not only is Mexico exporting less oil, it is exporting heavier oil. Pemex’s June statistics indicated that 89% of crude exports this year has been of the Maya variety, which averages about 22° gravity. Last year, 87% of crude exports was Maya, up from 83% in 2006. Mexico is now being forced to keep the lighter oil that it produces—Isthmus (34°) and Olmeca (39°)—for domestic consumption.

Production costs rising

The financial status of Pemex is particularly vexing given the rapidly escalating costs of energy production. CERA, for example, recently reported that Pemex’s global Upstream Capital Cost Index has doubled since 2005.18 To make matters worse for Mexico, CERA added: “Specialized deepwater equipment…showed the largest increase.”

More than half of Mexico’s prospective reserves lie in deep water. Chris Salden, British Petroleum’s vice-president of E&P in Mexico, reported that Pemex would need an investment of $200 billion during the next decade for deepwater work.19

Downstream costs are rising steadily as well. The Nelson-Farrar index of refining costs, reported in OGJ since 1946, has shown steady escalation across the board—labor, materials, and equipment. Escalating refining costs are an especially important issue given Mexico’s “need to build a refinery every 3-4 years over the next 2 decades” (OGJ Online, May 5, 2008).

While costs are rising worldwide, Mexico’s situation is exacerbated by the dramatic change in the source and quality of future oil supply. As the focus now shifts to other fields, it is becoming more apparent that Cantarell was the epitome of “low hanging fruit.”

Cantarell needed just 200 wells.20 The water at Cantarell is calm. Due to its shallow pay, straightforward geology, and high oil concentration, Cantarell has been relatively easy to exploit since its discovery in 1971.

Contrast this to the characteristics of the two fields Pemex views as being able to offset Cantarell’s decline in the next decade (see table).

The development of the Chicontepec basin will require an average of 1,000 wells/year for 15 years.21 This is more than Pemex currently drills in the entire country. The channel system has low permeability and mostly heavy oil in thin pay. This complex geology limits primary oil recovery rates to the 5-7% range and is the main reason development has been limited since oil was discovered there over 80 years ago.22 The heavy oil at KMZ also indicates production costs are destined to rise in Mexico.

Competing social needs

The emerging middle class and the country’s increasing dedication to social programs are requiring substantial expenditure, with much of the funding coming directly from Pemex. Energy revenues are siphoned off to pay for schools, roads, and medical, antipoverty, and other human welfare programs. The government has created a major recycling program and is building orphanages and affordable housing, while making low-interest loans available for business start-ups. It also has toughened emission standards.

In addition, Mexico has begun an historic struggle against the drug cartel activity that has paralyzed the nation. This effort will require even more resources that ideally would be used to help solve the problems of its oil industry. High oil prices are the main reason Mexico has the money to fight crime and poverty. In his attempt to persuade the US Congress to help fund Mexico’s drug battle, US President George W. Bush recently claimed Mexico has spent $3 billion to fight the drug war.24

Given these swelling social programs, reinvestment in oil exploration and development has become an afterthought, whereas E&P investment could discover more oil to support social programs.

In September 2007, Calderon called for “an urgent reduction in public spending to reduce the enormous dependence on oil revenue.”25

Institutional barriers

Private investment in Mexico’s oil industry is not permitted under the nation’s constitution. Mexican law limits Pemex to offer outside companies only multiple service contracts whereby Pemex pays a fixed cost for services on oil projects. The contractor does not receive any part of the earnings that Pemex may realize. Outside companies are not involved in E&P, and risk contracts are forbidden.

Pemex pays over 60% of its annual earnings in taxes and royalties, and Mexico’s Congress must approve its budget each year. These factors limit E&P investment. When Pemex generates above-average revenues, the government takes a larger amount of earnings through higher taxes. Conversely, when Pemex produces below-average revenues, the company’s budget is reduced to offset the deficits created in other sectors of the government.

Baker says that unless upstream regulatory changes occur, Mexican oil production probably has peaked.

Intellectual isolation

Despite the crucial role of deep water in Mexico’s energy portfolio, Pemex is sometimes absent from advanced technology meetings such as the Offshore Technology Conference (OTC) held annually in Houston.26

Modernizing into deepwater operations might be especially difficult because Pemex has little access to necessary educational infrastructure. Only two Mexican universities offer doctorates in deepwater geology, and the number of PhDs at Pemex from English-speaking universities is on the decline. Critics claim that Pemex managers are appointed on the basis of party loyalty rather than experience or knowledge. Such patronage is an important constraint because Pemex officials are replaced with each presidential administration, a new one being elected every 6 years.

Calderon recently engaged television and radio advertisements pushing for the public to be more open to reform. Baker believes internal reform is only part of the solution: “To improve Pemex, you need to have a view that…looks beyond Pemex,” and “Any particular effort to reform Pemex, as an effort itself, will not succeed.”27

Shields asserts there is no vision behind Calderon’s bill. “It is a proposal that tries to give something to everybody, and it does not seem to get very far in anything,”28 he said.

References

References are available from the author.

The author

Jude Clemente (judeclemente [email protected]) is an energy security analyst and technical writer in the Homeland Security Department at San Diego State University. He holds a BA in political science from Penn State University and an MS in Homeland Security from SDSU. He also holds certificates in infrastructure protection and emergency preparedness from the Federal Emergency Management Agency, the American Red Cross, and the US Department of Homeland Security. Clemente’s research specialization is energy security at the international level. He is a member of the National Defense Transportation Association and an energy advisor to B & S Corp. and Penn State’s Research Project on North American Energy Supply.