Special Report: Many states expand air permits; some submittals due in January

Some important US oil and gas industry states are requiring maintenance, start-up, and shutdown emissions to be added to air quality permits. Deadlines for some submittals are as soon as January 2009.

SIPs

For many years, oil and gas facilities have been required to obtain air quality authorizations as part of the new source review (NSR) permitting process for their air emissions. Traditionally, air quality permits covered only emissions from normal, ongoing facility operations (i.e., emissions from typical operations).

Emissions from maintenance, start-up, and shutdown (MSS) activities typically were not addressed as a part of air quality authorizations, mostly because state agencies were not requiring those emissions to be identified in air permit applications. Most agencies allowed these MSS emissions to be reported as excess emissions, and in general, both predictable and unpredictable MSS emissions have been reported as emission events, upsets, or malfunctions.

Over the past few years, however, the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has been paying increased attention to how states have addressed predictable MSS emissions in state implementation plans (SIPs) that every state is required to submit to EPA for approval. SIPs include provisions for all air quality regulations, including NSR authorizations as well as excess emissions reporting.

EPA’s position is that all periods of “excess emissions” are unallowable violations, and start-up, shutdown, and maintenance activities should be considered part of a facility’s normal operations and therefore subject to NSR requirements or a violation of air quality regulations.

Some states have provisions in their SIPs for companies to present an affirmative defense against civil penalties related to excess air emissions due to equipment malfunctions under certain conditions. EPA maintains, however, that state affirmative defense provisions are inappropriate for scheduled maintenance events because the “scheduled maintenance activities are predictable events subject to planning to minimize releases, unlike malfunctions (emission events), which are sudden, unavoidable, or beyond the control of the owner or operator.”1 Thus, “malfunctions,” as described by EPA are separate and distinct from scheduled predictable maintenance, start-up, and shutdown activities.

As a result of EPA’s increased scrutiny of state provisions and procedures related to predictable MSS emissions, state agencies have begun to address those emissions through NSR permitting. These initiatives require state agencies to revise their SIP provisions and clarify their positions on predictable and unpredictable MSS emissions.

Most of the states are adopting EPA’s historical position by continuing to allow reporting of unpredictable types of MSS emissions (i.e., malfunctions) as excess emissions and are beginning to authorize the predictable type of MSS activities through NSR permitting. Some of the states requiring MSS emissions to be included in air quality permits are states with large numbers of oil and gas facilities, including Texas, Louisiana, and New Mexico.

MSS

Since states have some discretion in how they structure their air quality permitting requirements, one state can have somewhat different requirements for MSS emissions than another state does.

The Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ) has considered requiring facilities to obtain authorization for unplanned but quantifiable and anticipated (QUAN) emissions, such as those from pressure-relief valves. When TCEQ promulgated its MSS permitting rules that are currently being implemented, however, it elected not to include any requirements to authorize QUAN emissions.

Thus, in Texas, only scheduled MSS activity emissions, which are a predictable type of MSS activities, can now be authorized through TCEQ’s NSR program. Since “unplanned” MSS emissions are not authorized, those unplanned QUAN emissions will continue to be covered by rules addressing unauthorized emissions under the excess emissions reporting program.

Meanwhile, the New Mexico Environmental Department (NMED) is still considering whether to require facilities to obtain authorization for emissions from anticipated but unplanned activities, which would be similar to the QUAN emissions that TCEQ considered. As can be seen in this example, the types of emissions that a state agency deems subject to permitting vary among states; individual state requirements must be consulted.

MSS permitting: obstacles, concerns

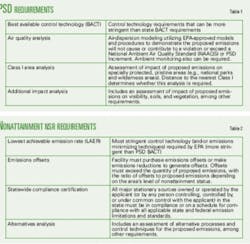

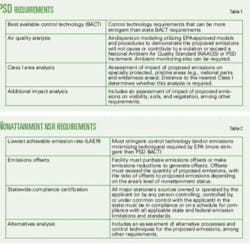

As a part of NSR, many states require state best available control technology (BACT) to be applied to any emission sources that are included in air quality authorizations. While state BACT requirements may not be as stringent as BACT requirements related to the US “Prevention of Significant Deterioration” (PSD) BACT requirements (discussed presently), state BACT can still result in additional control technologies being required for maintenance activities (and also start-up and shutdown emissions).

Besides the additional cost to implement BACT requirements, there can also be additional labor requirements, depending on what additional steps would be required to minimize emissions during MSS events. Additional staff time will be required for documenting compliance with the air permit requirements related to MSS emissions and emissions reduction efforts.

One obstacle for obtaining a permit for MSS air emissions can be documenting, through air-dispersion modeling, that the proposed emissions do not cause a violation of ambient air quality standards. Permits cannot be issued unless the emissions to be permitted can be shown not to cause a violation of ambient air quality standards such as the National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS) and state ambient air standards, including state toxic air pollutant standards.

Since many oil and gas facilities have property lines near their air emission sources, off-site impacts could be high for some MSS emissions. Even for emission sources some distance from property lines, the magnitude of MSS emissions can cause problems with air-dispersion modeling results.

These considerations can affect decisions about how to conduct MSS activities and whether additional operational measures for emissions reductions should take place. In some cases, a company may want to explore its options to see what is feasible before it submits information to the state agency. In light of the potential permitting problems for some current MSS activity methods, some of the alternative methods of conducting infrequent MSS activities should be explored long before a permit application will be required.

In Texas, facilities are being required to prepare and submit to the TCEQ air-dispersion modeling analyses for pollutants with ambient air quality standards as well as for pollutants with screening levels under the Texas air toxics program. One common problem with modeling air emissions from MSS activities is demonstrating compliance with standards with short averaging periods (e.g., 1 hr to 24 hr).

In particular, the sulfur dioxide (SO2) emissions from flaring gases with high hydrogen sulfide (H2S) content can cause problems with meeting ambient SO2 standards, especially because there are federal SO2 standards with 3-hr and 24-hr averaging periods and state standards with even shorter averaging periods.

State air toxics requirements can also provide difficulties in the permitting process. One common problem that arises for various organic compounds is emissions from various tank MSS activities, particularly for tanks near a property line. The amount of time required to resolve such issues should not be underestimated in planning an MSS permitting project timeline.

Depending on the size and type of operations at a facility, another obstacle to obtaining authorization for MSS emissions can be the triggering of federally mandated NSR requirements, such as PSD and Nonattainment New Source Review (NNSR) requirements.

If the proposed MSS emissions exceed certain thresholds, the facility will have to address PSD or NNSR or both, which have even more stringent requirements than the typical MSS state permitting requirements (Tables 1 and 2). Thus, it is important to propose high enough emissions to allow sufficient operational flexibility, but at some point, a closer look at the level of flexibility may be required due to additional requirements associated with the proposed emissions levels.

In Texas, several petroleum refineries and chemical plants (the first two categories of sources to submit permit applications for MSS emissions) have received requests from the TCEQ either to comply with the additional requirements of PSD and NNSR or provide justification for why their proposed levels of MSS emissions do not trigger PSD or NNSR requirements.

Strategies

Several strategies can be advantageous to a company as it addresses MSS permitting requirements.

Review the earliest MSS permits issued in the state and comment on provisions that appear unduly restrictive or costly during the public comment period because the earliest permits a state issues set precedent for future permits they issue.For example, in Texas, petroleum refinery permit applications were the first ones to be submitted. The Texas Oil and Gas Association (TXOGA) has been conducting extensive discussions with the Texas state agency, TCEQ, about members’ concerns with some permit conditions proposed by TCEQ. Besides the permit conditions causing concerns for refineries, however, some permit conditions may have effects on upstream oil and gas facilities that they would not have on refineries, as the chemical industry has seen in its review of the proposed permit conditions.

In Louisiana, the Department of Environmental Quality has started requesting information on MSS activities when air-quality permit applications are submitted for permit amendments or renewals. Thus, the Louisiana approach means that permits for multiple industries may be in the first group of permits with MSS requirements.

- Work with state industry groups to address contentious issues with state agencies. Those issues can be in the form of regulations, permit conditions, or even policies and guidance.

For example, the New Mexico Oil and Gas Association (NMOGA) and Independent Producers Association of New Mexico (IPANM) were able to work a compromise at the last minute on the proposed New Mexico MSS regulation.

One substantial negotiated change was from every emissions event automatically triggering a requirement for submittal of a root-cause analysis to NMED to an emissions event root-cause analysis being required only upon specific request by the NMED.2

- Budget for the resources required to meet MSS permitting requirements and do not underestimate the effort required to show compliance with the air dispersion modeling requirements.

- Budget for the increased cost of maintenance activities due to potential BACT requirements.

- Start early identifying MSS activities. A company’s environmental staff may want to review past records besides talking with operations and maintenance staff to develop a comprehensive list of MSS activities for permitting based on history and anticipated future activities.

- Facilitate communication between environmental staff members responsible for various sites (and various states).

- Evaluate MSS scenarios to determine which activities could happen simultaneously and which would not. Sometimes air-dispersion modeling problems can be alleviated or reduced by segregating emissions from activities that would not occur simultaneously.

- Develop an MSS activities checklist if the company has several facilities subject to MSS permitting requirements. The checklist can be simply on paper to make sure that all MSS activities are identified, but an appropriately designed checklist in a spreadsheet or database format can be a productive step toward developing the necessary emissions calculations.

Deadlines

Deadlines for obtaining authorizations for MSS emissions vary by state and the individual state regulations should be consulted. Three states near the top of the list in terms of oil and gas production, however, are taking a deliberate approach in addressing MSS emissions through permit applications.

In Texas, the TCEQ has set deadlines for facilities based on standard industrial classification (SIC).3 For oil and gas facilities in SIC Codes 1311 (Crude Petroleum and Natural Gas), 1321 (Natural Gas Liquids), 4612 (Crude Petroleum Pipelines), 4613 (Refined Petroleum Pipelines), 4922 (Natural Gas Transmission), and 4923 (Natural Gas Transmission and Distribution), the deadline for submitting an air quality permit application or otherwise obtaining authorization for MSS emissions is Jan. 5, 2012 (reference 30 TAC 101.222(h)).

Facilities in other SIC categories have separate deadlines listed in the Texas rules. With the TCEQ considering additional options for authorizing oil and gas industry MSS emissions, now is a good time for oil and gas companies to be engaged with TCEQ on the direction that will be taken in this evolving area of air quality permitting.

The New Mexico Environmental Department (NMED) is taking a slightly different approach. The first deadline of Jan. 27, 2009, applies to all facilities in New Mexico, including all oil and gas facilities.

By Jan. 27, all facilities are to revisit what NMED calls start-up, shutdown, and maintenance (SSM) emissions and determine whether the facilities’ owners or operators will need to obtain a permit or change permit status. If a permitting action will be required, the NMED must be notified by Jan. 27 that a permit change is indicated. The agency will then “call” for permit applications based on their priorities.

The stance of the Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality (LDEQ) is that routine MSS emissions should be added to a facility’s air quality permit at the earliest opportunity if those emissions are not already in the facility’s permit. In fact, permit writers at LDEQ are currently requesting information about MSS emissions during their reviews of permit amendment and renewal applications if the facilities do not have MSS emissions already authorized.

In Louisiana, there is no specific deadline for permitting MSS emissions, but facilities can be subject to enforcement actions if they are found to have unauthorized MSS emissions. Thus, companies with facilities in Louisiana should be evaluating their compliance situation on MSS air emissions now.

Other states

As indicated by this sampling of states, the requirements for MSS emissions vary by state. In some states, such as Texas, New Mexico, and Louisiana, obtaining an air permit that includes MSS emissions is mandatory, while in other states it is voluntary.

For example, on a case-by-case basis, the Arkansas Department of Environmental Quality has allowed some facilities to include MSS activities in their permits to avoid upset condition reporting for those MSS emissions.

Due diligence

This review should make clear how important it is to check on the situation in a particular state. MSS permitting requirements are evolving, and some states are currently amending their emissions events and excess emissions rules, which can affect MSS permitting requirements.

Some states are requiring immediate action. Companies should be prepared to address air emissions for MSS activities at their facilities. It is important to plan for the financial and personnel resources that will be needed to comply with MSS permitting requirements.

References

- EPA comment on excess emissions, TCEQ meeting, Mar. 4, 2005.

- Compare final adopted rule 20.2.7.114 NMAC (effective Aug. 1, 2008) with proposed rule 20.2.7.113 NMAC (Exhibit 1 for the final rule package at http://www.nmenv.state.nm.us/aqb/prop_regs.html).

- 30 TAC 101.222(h).

The author

Gary Daves ([email protected]) serves as a principal consultant in Trinity Consultants’ Houston office. In 13 years with Trinity, he has gained extensive experience assisting clients in more than 20 states with regulatory compliance and strategy, including regulatory applicability determinations, performing compliance audits, Title V and New Source Review permitting, compiling emission inventories, and performing emission calculations and air dispersion modeling analyses. He also provides technical supervision of Trinity staff performing similar duties. Daves holds a BSME (magna cum laude) from the University of Arkansas and MSME from Georgia Tech. He is a licensed professional engineer in Louisiana.