COMMENT: Did Caspian summit share the sea or Iran’s oil riches?

The Iranian oil and gas industryalthough about a century oldhas never been so derelict, poorly managed, and near bankruptcy as it is today. Russian President Vladimir Putin has recognized the deterioration of the Iranian petroleum industry as an opportunity for exploitation. In particular, he has manipulated the Islamic regime’s leadership through deception and false promises of the “benefits” of cooperation with Russian companies in the oil and gas sectors.

Isolated and under extensive and serious sanctions by western countries, the Islamic Republic of Iran has looked to the north and has seen Russia as a country that follows the same path and goals as the Islamic fundamentalists in Tehranthat of challenging the American presence in the region. Russia has opposed the US’s pushing for tougher sanctions against Iran and has called for open dialogue with Tehran and lighter sanctions against Iran.

Caspian Sea conference

When the 2-day summit of the Caspian Sea’s five littoral statesRussia, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, Iran, and Azerbaijanwas held in Tehran in mid-October 2007, a large Russian delegation with an extensive list of demands accompanied the president of Russia to Tehran. Putin, in order to save the Islamic regime from ever-increasing isolation, not only traveled to Tehran but also invited Islamic Republic President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad to Moscow.

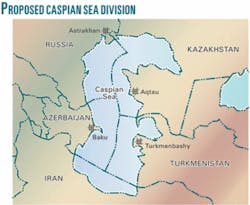

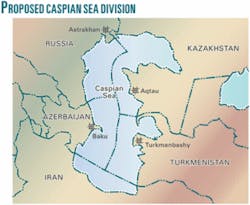

Since the collapse of the former Soviet Union, the status of the inland sea has been a source of long-term disagreement among the five littoral countries. The Caspian Sea, under the 1921 and 1940 treaties, originally was divided between Imperial Iran and the former Soviet Union. Currently, Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan, and Russia have so far agreed to divide the upper portion of the Caspian seabed according to national sectors along the so-called modified median line, leaving the sea itself for common use. This has enabled the three states to agree upon the delimitation of the Caspian seabed on adjacent parts and conclude bilateral agreements to exercise sovereign rights on the use of mineral resources. However, Turkmenistan and Iran apparently are not happy with these divisions and are struggling to have a bigger share of the sea than they now have (see map).

Considering the statements made by Kazakhstan President Norsultan Nazarbajev upon his arrival in Tehran, the early treaties dictating the sharing of the Caspian Sea between the Soviet Union and the Iranian government now are null and void. Evidently, the summit was not about the Caspian issue. Rather, the Russian president has pushed for control and hegemony of both the natural resources of Iran and the riches of the whole region.

The summit produced aggressive comments by the nondemocratic leaders of Iran and Russia who, deeply wary of American influence, are admonishing against outside interference by increasingly assertive resource-rich countries in the Caspian Sea area.

Sharing Iran’s oil, gas

Ahmadinejad and Putin, under a treaty signed in Tehran, have agreed to the initial participation of two Russian companies in the development of oil and gas deposits in Iran. They are OAO Lukoil in the oil sector and OAO Gasprom in Iran’s South Pars gas field. This provision has been included in the joint statement by the presidents of both countries.

Apparently, the two sides agreed to develop direct contact between oil and gas companies of the two countries aimed at concluding concrete, mutually beneficial commercial agreements on joint work in all segments of the oil and gas industry. Particular attention was given to cooperation in the exploration, production, and transportation of oil and gas.

In light of the near collapse of the Iranian petroleum industry as a result of sanctions and the lack of investments by the West, the “coordination of marketing policy” stressed by the document can be interpreted as the controlling and managing of Iranian oil and gas by the Russian companies, from exploration to exporting terminals and marketing.

Pipeline vs. environment

Putin is eager to maintain his country’s dominance over the delivery routes of oil and gas to the West from Central Asian producers and the Caspian’s eastern shore. Therefore, in the Tehran summit he warned that energy pipelines from the region should be built only if all five nations that border the inland Caspian Sea support them.

The Russian leader also proposed building a canal as soon as possible to connect the Caspian Sea with the Black Sea to establish an East-West transport corridor for the obvious reason of challenging and rivaling the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan pipeline, which has been endorsed and financed by western oil companies and financial organizations.

He also desired to undermine the notion of transporting oil and gas from Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan by pipeline from the eastern shore of the sea to the western shore for export. The issue of transporting oil and gas and laying pipelines under the Caspian Sea has always been a point of contention among energy producing nations in the region, mainly Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan.

At the summit, the Russian leader simply demanded that major energy projects having environmental risks for the Caspian should be discussed with all five Caspian nations and approved by consensus. Putin added that environmental security must become a yardstick for measuring the safety of all projects, especially in the tapping and transporting of energy resources. Putin also emphasized that the condition of the Caspian natural environment and its sturgeon population demands immediate measures to prevent environmental damage. Certainly, Putin has gained an additional argument in support of his position regarding the elimination of the Trans-Caspian pipelines.

In Tehran Putin said, “Projects that may inflict serious environmental damage to the region cannot be implemented without prior discussion by all five Caspian countries,” ostensibly suggesting that each country, including Russia, should have a virtual veto on energy transport across the sea. Although protection of sturgeon, other fish, and caviar is a legitimate concern, critics believe Russians have too often used Putin’s “concerns about the environment” as a convenient pretext to squeeze international companies working in Russia out of oil and gas agreements. Further, the statement by the Russian leader translates as a pretext to increase western worries about Moscow’s increasing use of its energy as a tool for blackmailing the West.

Meanwhile, a week before Putin’s arrival in Tehran, ministers from three East European countriesUkraine, Lithuania, and Polandalong with Azerbaijan and Georgia, signed an agreement for the construction of an oil pipeline connecting the Black and Baltic seas (OGJ, Oct. 22, 2007, p. 34). The agreement was aimed at implementing regional energy security while reducing dependence on Russian crude oil and transportation. Russia has consistently wielded its oil and gas resources as a diplomatic weapon, hence punishing the former Soviet Union satellite nations for not toeing the Kremlin line. Therefore, the recent agreement signed by these five countries is considered to be a victory mainly for Eastern European countries.

Furthermore, the three former Soviet republics (Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and Turkmenistan), together with the European Union and the US, have made inroads in gaining access to Caspian Sea energy reserves, with major projects in Azerbaijan’s rich deposits. The US and Europe want new pipelines to carry oil and gas across the Caspian from Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan to Baku in Azerbaijan and farther west, bypassing Russian soil. However, Putin in Tehran underlined his strong opposition to such efforts to bypass Russia and thus diminish its control.

A joint naval force

Among priority spheres for cooperation, Putin highlighted comprehensive security and stability in the region, includingwith emphasisthe protection of oil and gas production facilities. The Russian leader said he is interested in a firm security program in the Caspian Sea and proposed that the five littoral states set up a joint naval force, to be called Caspian Forces, for strategic cooperation on the Caspian Sea. Apparently, cooperation under the project could be coordinated within the framework of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization.

Summit host Ahmadinejad also emphasized the firm policy and urgent need to keep westerners out of the region. And Putin emphasized that no Caspian nation under any circumstances should offer or allow its soil to third powers for use of force or military aggression against any Caspian nation. The Caspian states should prohibit the use of their territories by any outside powers for military force against any country in the regionan obvious reference to longstanding rumors that the US has been planning to use Azerbaijan soil as a base for possible military attacks against Iran. Putin and Ahmadinejad have consistently pushed for the inclusion of this provision in Tehran declarations.

Sea issues unresolved

However, the five Caspian nations appeared no closer to resolving the border and other legal issues of the sea, which have been in limbo since the Soviet Union collapsed. The absence of transparency has led to conflicting claims to seabed oil and gas deposits, including a dispute between Turkmenistan and Azerbaijan, and also between Iran and Azerbaijan on their offshore borders. However, as mentioned before, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and Russia have signed their own bilateral deals dividing about 64% of the sea among them.

Except for the accomplishment of selling out the Iranian oil and gas industry, the summit could well be described as a summit of postponed problems, including no common agreement among the five littoral countries regarding the legal issues involving the Caspian Sea.

The author

Mansour S. Kashfi ([email protected]) is president of Kashex International Consulting. He also is a faculty member at Eastfield College in Dallas. Kashfi has over 40 years of research experience in a wide range of oil and gas, geology, policy, and economic issues, with expertise in the petroleum geology of the Middle East and world oil market development. He has published more than 50 books and articles. Kashfi holds a BS degree in geology from University of Tehran, an MS in geology-subsurface stratigraphy from Michigan State University, and a PhD in geology-tectonics and sedimentology from University of Tennessee.