Steadily rising refined product demand in the Middle East is inducing significant refinery investments in the region. These offsetting factors complicate the outlook for refined product exports and imports from countries in the Middle East.

Development of the Middle East’s oil industry during the next few years will be crucial to the outlook for the global oil industry. The region is crucial from a crude oil supply perspective and appears likely to increase its current 31% share of global crude oil and condensate production.

The region, however, is also a substantial net exporter of refined products: in 2007, refineries produced about 6.5 million b/d compared with regional consumption of about 5.2 million b/d. Because regional oil product consumption is increasing steadily and a plethora of refinery developments are proposed, potential exists for a rapid and substantial change in this position.

The region comprises countries that are very different, and these differences have been reflected in their energy and industrial policies. Countries such as Iran and Saudi Arabia have substantial indigenous populations and low or moderate incomes on a per-capita basis; for these countries, the creation of employment and supply of low-cost energy have been priorities.

Most Middle East countries are rich in oil or natural gas resources and are benefiting from currently high prices; Jordan, Lebanon, and Israel are exceptions. For Qatar and UAE, substantial natural gas resources have displaced oil products in the power and industrial sectors. Iran, however, with the world’s second-largest natural gas reserves, has been unable to produce sufficient natural gas to satisfy internal demand.

Wars and sanctions have also shaped the region’s refining industries. Iran and Iraq particularly have suffered from the limited availability of foreign technology and expertise; Iraq’s oil industry is currently struggling to recover from more than 15 years of underinvestment due to civil disorder. Despite efforts to boost local expertise, the region’s oil and gas industry remains heavily dependent on foreign equipment, technology, and services.

Although there are differences amongst countries in the region, there are also similarities, including a general desire for supply security. This has been one of the key forces of historical refining industry developments.

Regional product demand

Since 2004, higher oil prices and associated revenues have stimulated economic growth in the Middle East.

Fig. 1 shows that regional GDP grew at an average of 5.5%/year during 2004-07, spurring steady growth in oil product demand.

Overall refined product consumption increased an average of 2.8%/year during 2005-07. Growth in gas oil-diesel averaged 3.3%/year, and gasoline 2.3%/year. Overall product consumption will remain close to 3%/year through the next decade, with light product growth somewhat stronger than that for heavy fuel oil.

This outlook is sensitive to many factors, including economic growth, oil prices, and availability of natural gas. If natural gas availability for power generation and desalination is less than expected, fuel oil demand could increase more rapidly.

Regional product trade

The Middle East is a net exporter of most refined products. LPG, naphtha, and fuel oil are exported mainly to Asia. Middle distillates, jet fuel-kerosine, and gas oil-diesel are exported to Asia and Europe.

Europe is structurally short of middle distillates, although most of its gas oil-diesel is supplied from CIS, principally Russia. Middle East naphtha, including natural gasoline-type condensate, is mainly exported into Asia as an olefin plant feedstock.

Fig. 2 shows how net trade has developed during the past 5 years for the main product groups.

The Middle East is short of gasoline, primarily because of Iran’s appetite for imports. Iranian domestic gasoline prices are heavily subsidized, which has boosted domestic demand and led to unauthorized exports into adjacent markets.

Efforts to curtail such exports, including the introduction of rationing with the assistance of a smart card system, have cut import requirements; but recent indications are that imports are again rising. Higher domestic prices are needed in the longer term.

Middle East refined product demand will continue to rise. Future imports and exports will reflect demand trends, although considerable uncertainty surrounds the future development of the region’s refining industry.

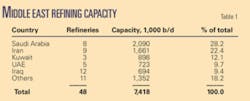

Refining industry profile

With 48 refineries and an aggregate nominal capacity of about 7.4 million b/d, the Middle East contains just more than 8% of global refining capacity (see table).

Saudi Arabia is the region’s largest refiner, with Iran in second place. Kuwait, however, reflecting its relatively limited domestic market is the region’s largest exporter. Refineries in Iran, Kuwait, and Saudi Arabia have been operating at full capacity. Sabotage of process facilities and crude pipelines has left Iraq’s industry recently achieving only about 60% utilization, despite the country being short of product supplies.

Since 1991, refineries in Iraq have also suffered from a lack of new investment, modernization, and even adequate maintenance, essentially caused by two wars and sanctions. Many of the country’s smaller facilities are reportedly inoperable.

Refinery projects

In the Middle East, as in other parts of the world, stronger margins since 2004 have sparked new refinery projects. When analyzing the industry’s outlook, one must assess which of these projects will move forward with schedules more or less in-line with those announced.

We recently reviewed worldwide refinery projects—out of 275 announced refinery projects, we feel that about 60% of these, representing about 75% of capacity, are speculative.

Projects involving established, financially strong players with a local crude supply and designed to serve local markets are in most cases likely to be sound. Projects involving new entrants, without a local crude supply and focused on export markets may also succeed, but will be more difficult to implement.

Fig. 3 shows Purvin & Gertz’s assessment of Middle East refinery projects likely to be implemented in the next 6-7 years. This shows projected additions to crude distillation capacity and fuel oil conversion capacity. Fuel oil conversion capacity additions include coking, catalytic cracking, and hydro-cracking projects.

During 2008-15, about 1.8 million b/d will be added to the region’s crude distillation capacity and, more crucially, about 175,000 b/d of coking, a similar amount of vacuum gas oil and residue catalytic cracking, and about 270,000 b/d of hydrocracking.

Many of these projects are designed to process heavier crudes and will make an important contribution to easing current pressure on fuel oil conversion capacity.

An uncertain future?

Any projection of refinery investments is imperfect. Projects will be delayed, some may be abandoned, and others, not currently viewed as likely, may be implemented. The views of project sponsors with regard to future capital cost trends and refining margin trends clearly differ and affect investment decisions accordingly.

Since 2003, refinery project costs have risen spectacularly. Prices of commodities such as steel and concrete have surged, mainly due to booming economies in Asia. Construction labor costs have similarly risen. Project costs, however, have risen even more strongly than commodity and labor costs.

Purvin & Gertz has developed a construction cost index to represent typical refinery and other similar downstream project cost escalations (Fig. 4). Lump-sum, turnkey project costs have risen by about 80% since 2003.

Pressure on the supply of materials and equipment has led to greater uncertainty with regard to availability and delivery timing of materials and equipment. Quality control problems have also escalated as new and less-experienced equipment manufacturers are being used.

EPC contractors have passed increased risks on to operating companies or project sponsors by increasing their prices. They have also been able to increase their margins from the depressed levels seen pre-2004.

It is difficult to predict where project costs will settle out. Materials and equipment supply industries and EPC companies are increasing capacity; prices and lead times for major equipment have in some cases stabilized or declined. It is likely that further cost increases will occur.

It is also likely that future demand for materials, equipment, and services will prevent supplier prices and project costs from falling back to pre-2004 levels. Although this may appear a somewhat negative view from the perspective of refining industry investments, in practice it is uncertainty regarding project costs rather than high costs that can be more damaging.

Fig. 5 shows historical margins for representative refineries in the US, Europe, and Singapore.

A common view is that refining margins are a function of oil prices. Even more mystifying is the common reaction to refinery capacity problems: an increase in crude oil prices.

The fact is that refining margins reflect supply-demand pressures in the context of refining capacity. A shortage of capacity leads to strong margins and low capacity utilization leads to margins languishing in the breakeven range for marginal types of capacity.

The surge in demand for refined products that initiated the rise in oil prices in 2004 also tightened refining capacity. Problems due to hurricanes in the US Gulf in 2005 aggravated the situation.

Product supply tightened and refining margins increased. In particular, increased production of heavy, sour crudes found the refining industry with insufficient fuel oil conversion capacity and, in some cases, desulfurization capacity. Light product supply tightened, heavy fuel oil supply increased and price differentials between light and heavy products, and consequently between light and heavy refinery feedstocks, increased.

Fig. 5 shows how complex refinery margins around the world reacted.

Not surprisingly, the surge in margins and light product spreads has led to renewed interest in refining investments. Substantial capacity additions are now being implemented.

Their effect will naturally depend on how product demand develops, but the balances that we analyzed suggest that refining capacity additions in general and fuel oil upgrading capacity additions expected during next 5-7 years will exceed requirements. This indicates a moderation of refining margins relative to levels seen in 2005-07.

Refining outlook

Expected Middle East refining capacity additions are part of the wider trend. Margins for export-oriented refineries will soften somewhat compared with recent levels. A collapse, however, will not occur. Investment cost inflation has slowed the pace of capacity additions to some extent, and demand for refined products will continue to grow.

A key variable will be the future cost of refining industry investments. The refining industry is an essential part of the world’s energy supply and, assuming that oil demand growth continues, new investments in refining capacity will be needed.

In most cases, these investments will be made only if supported by adequate returns. Poor returns would lead to a slowdown in investment, new capacity shortages, and an upward correction in margins and returns. In the longer term, high investment costs would not lead to a lack of investment, they would simply mean that margins had to be higher to generate adequate returns.

This is where uncertainty about future investment costs becomes an issue. If future investment costs were lower than recent levels, margins needed to support new investments would also be lower. An investment made in a high-cost environment could generate disappointing returns if future investment costs were lower. In refining, as in so many capital intensive industries, timing can be crucial.

Regional developments will also influence the economics of Middle East refining investments. On the supply side, rehabilitation and upgrading of Iraq’s refining industry could have a significant effect, although timing is difficult to assess. Iranian refinery projects, if implemented as announced, would also have a major effect, particularly with regard to the region’s gasoline balances.

The start-up later this year of Reliance’s refinery expansion at Jamnagar in northwest India will increase regional gasoline supply substantially. Before 2005, Persian Gulf gasoline prices and trade data indicated that India was the region’s marginal supply source, but during 2005-06 this position changed.

When Middle East import requirements increased, cost-insurance-freight prices strengthened and Asia and Mediterranean Europe became the region’s marginal suppliers. The Reliance start-up will inject a large new gasoline supply stream into the region and may well reverse the changes seen since 2005.

Overall, the Middle East refining outlook appears sound, provided that capacity additions are not excessive. Global and regional growth in product demand will support new investments, although project timing will be important if returns are to be maximized.

The region’s current gasoline supply deficit may encourage the development of gasoline-oriented projects. Gasoline market softness, however, could develop rather quickly as a result of demand and refining developments in Iran and India and more widely. This suggests that gasoline-oriented projects should be analyzed particularly carefully.

The author

Michael Corke ([email protected]) is senior vice-president and manager for Purvin & Gertz Inc., Dubai, responsible for the firm’s consulting activities in the Middle East. Before joining Purvin & Gertz’s London office in 1985, Corke worked for BP and Murphy Eastern Oil Co., a subsidiary of Murphy Oil Corp., where he was involved in oil trading, refinery construction, joint venture refinery management, and North Sea operations. He holds a BSc in chemical engineering from Leeds University, UK.